A Comprehensive Review of Dentinal Hypersensitivity

A variety of options is available to treat this common patient complaint.

This course was published in the July 2013 issue and expires July 2016. The author has no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Discuss the prevalence of dentinal hypersensitivity.

- Explain the hydrodynamic theory.

- Identify the possible causes of dentinal hypersensitivity.

- List the treatment options available for dentinal hypersensitivity.

Dentinal hypersensitivity is one of the most common patient complaints.1 It affects as many as 57% of dental patients, and seems to peak between the ages of 20 and 40.2 The prevalence of hypersensitivity is slighty higher among women,3 with canines and premolars of both arches most commonly involved.4 The pain caused by hypersensitivity is often chronic with acute episodes.5

Hypersensitivity is defined as a “short, sharp pain arising from exposed dentin in response to stimuli, which are usually thermal, evaporative, tactile, and osmotic or chemical that usually cannot be attributed to any other form, dental defect or pathology.”6 Usually, the pain is localized and of short duration. This differs from pulpal pain, which is protracted, dull, aching, poorly localized, and lasts longer than the applied stimulus. The distress caused by hypersensitivity can range from minor to severe. Severe cases may make eating and drinking difficult, especially very hot or cold substances. However, the pain experienced by individuals with sensitivity is highly subjective, and the intensity is episodic in nature. Unfortunately, patients are rarely able to isolate the relevant tooth.7

To uncover and isolate the causes of sensitivity, clinicians usually rely on exposing the suspected tooth to an air blast or hot or cold liquid to elicit a response from the patient. The use of a rubber dam to isolate the tooth can be helpful in this process.

HYDRODYNAMIC THEORY

The “hydrodynamic theory” is the most commonly agreed upon cause of hypersensitivity. Kramer8 and Brännström9 confirmed and expanded on this theory that establishes a relationship between applied pressure, air blasts, and chemical stimuli to dentin fluid shifts that occur in response to these stimuli.7 In the original research, Br?nnstr?m ground through the enamel and into the midcoronal dentin of premolars in children whose teeth were going to be extracted for orthodontic purposes. The children’s cross-sectional dentin tubules were exposed to saliva for 1 week, which resulted in increased sensitivity. Initially, these teeth were covered by a smear layer, but by the end of the week, it had disappeared, thus making the dentin increasingly hyperconductive.9 Dentin permeability varies and can quickly decrease.10

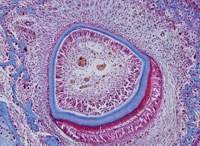

The evidence supporting the hydrodynamic theory is based on in vivo studies in both human and animal subjects. The distribution of nerves in dentinal tubules varies, with about 40% occurring over the pulp horns and fewer located in the cervical dentin. It seems that open dentinal tubules are necessary for exposed dentin to become sensitive (Figure 1). The more open, large tubules that are present, the more sensitivity a patient will experience. Open tubules demonstrate high hydraulic conductance, and if the tubules are blocked, fluid flow is decreased. This provides a means for a variety of treatment options.11

Magloire et al states that external stimuli result in dentinal fluid movement and odontoblasts and/or nerve complex reaction may be a distinctive mechanosensory system, providing a new role for odontoblasts as sensor cells. Information transfer between odontoblasts and axons may be the result of mediators in the gap space between odontoblasts and axons as evidenced by nocioceptivetransducing receptors and trigeminal afferent fibers, and expression of reputed effectors by odontoblasts (Figure 2).11

CULPRITS BEHIND SENSITIVITY

Gingival recession, periodontal diseases, cracked teeth, abrasion, erosion, and tooth fracture may cause hypersensitivity. All of these problems result in exposed dentin, which creates an environment where stimuli cause dentin tubular fluid movement that activates nerve fibers, causing pain. The exposed dentin may result from removal of cervical cementum during scaling and root planing, finishing and polishing of restorations, or extreme toothbrushing by the patient— especially after the ingestion of acidic food or drink. Regurgitation by patients with bulimia produces acid exposure, and subsequent brushing can lead to loss of tooth structure.1 Pain can be localized or general in nature, and may affect a variety of tooth surfaces, either together or individually.12

PERIODONTAL DISEASES

Dentinal hypersensitivity is often seen in patients with periodontal diseases.13 Studies show that the incidence of dentinal hypersensitivity increases 1 week following periodontal surgery, and resolves by 8 weeks.14,15 Younger patients demonstrate more sensitivity compared to older adults for which the sensitivity takes longer to resolve. Scaling and root planing can also cause sensitivity for several days after treatment, which subsequently decreases.

GINGIVAL RECESSION

Gingival recession results in exposure of root surfaces and possible sensitivity. Buccal bone provides most of the blood supply for the buccal gingiva, and any loss of buccal bone will result in a decrease in gingiva.14 Thin or fenestrated bone, tooth anatomy, tooth position, or orthodontic movement may result in recession. Excessive toothbrushing with dentifrice can also cause recession.15

CRACKED TEETH

The signs and symptoms of cracked teeth may vary depending on the severity. Patients usually will experience acute pain with mastication but upon removal of the stimulus, the pain subsides. If the pain extends to the pulp or periodontal ligament, it will persist.16

EROSION

Erosion is defined as a loss of enamel through chemical dissolution by acids that are not of bacterial origin. There are three types of erosion: extrinsic (diet, lifestyle, or environment); intrinsic (gastric acid); and idiopathic (unknown origin).17 The unionized acid diffuses into the interprismatic areas of the enamel and creates a dissolving of the mineral in the subsurface area.18 In the initial stage, the tooth surface is dull due to demineralization, but the tooth is not hypersensitive because the dentin with open tubules is not exposed.

Composite can be used to seal the enamel to restore the normal contour and also to prevent dentin exposure.19 Restoring the tooth will improve oral hygiene and reduce any possible pulpal involvement, toothbrush/dentifrice abrasion, and acid erosion.20

ABRASION AND ATTRITION

Abrasion is the loss of tooth structure by mechanical forces from a foreign element, and it may cause sensitivity.21 Attrition is tooth-to-tooth contact, which results from occlusal function or parafunction, such as bruxism, and can cause loss of tooth structure on the occlusal surfaces and incisal edges.22

ABFRACTION

Abfraction may occur when disproportionate cyclic, nonaxial tooth loading leads to cusp flexure and concentration of stresses in the susceptible cervical region of teeth. These cervical lesions, caused by occlusal stresses, lead to weakening of the cervical tooth structure and can cause enamel, cementum, or dentin to chip away from the cervical aspect of the tooth.23 Lee and Eakle24 first described lesions that may result from tensile stresses. They established that an abfraction lesion is often located at or near the fulcrum in the area with the greatest concentration of tensile stress, is typically wedge-shaped, and displays a size proportional to the degree and incidence of tensile force application.

TOOTH WHITENING

External tooth whitening often causes dentinal hypersensitivity. The use of hydrogen peroxide or carbamide peroxide may allow the hydrogen peroxide to infiltrate through the enamel and dentin to the pulp. The glutathione peroxidase and catalase in the pulp then don’t have enough time to inactivate the hydrogen peroxide, which may cause sensitivity. In addition, all bleaching gels are hypertonic and osmotically draw water from the pulp through the dentin and enamel to the whitening agent. This can potentially stimulate intradental nerves.25

TREATMENT OPTIONS

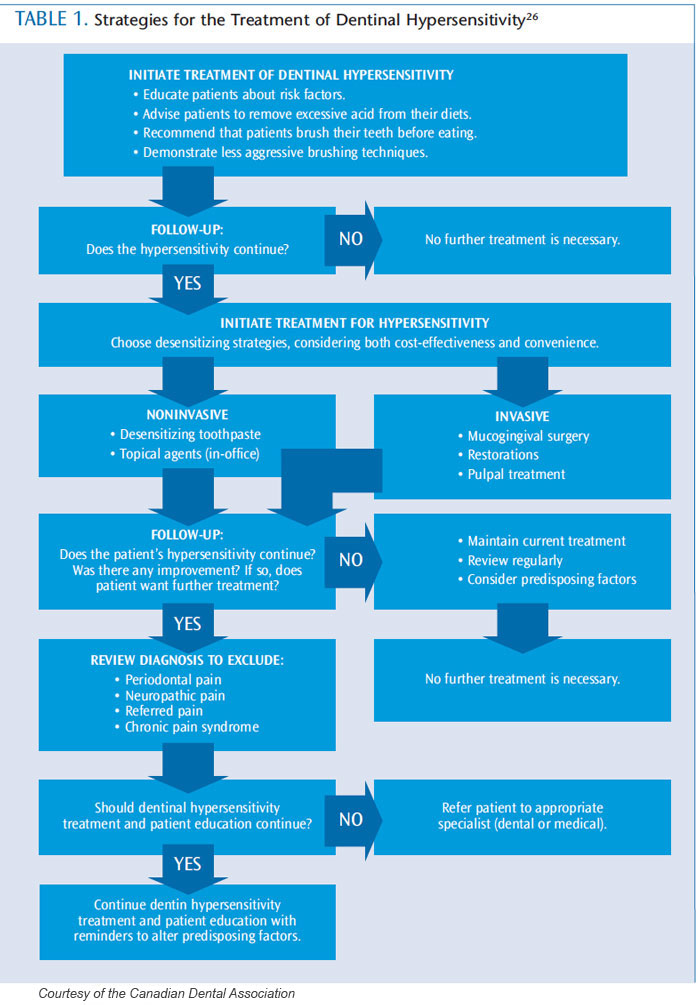

A variety of treatment options are available for both at-home use or in-office application (Table 1 provides a flowchart regarding treatment options).26 Their mechanism of action is typically nerve desensitization, protein precipitation, plugging dentinal tubules, sealing dentin, or ablating dentin with a laser. The most commonly used treatments include anti-inflammatory agents, protein precipitants, tubule-occluding agents, and tubule sealants. The most conservative approach should be implemented initially, with more aggressive treatments suggested if pain relief is not achieved.27

AT-HOME STRATEGIES

Recommend a dentifrice with potassium salts (potassium nitrate, potassium chloride, or potassium citrate) or fluoride as the first line of defense for sensitivity. Potassium ions diffuse along the dentinal tubules, which block nerve action, dulling the pain associated with hypersensitivity. Potassium salt dentifrices are effective, but they may require 2 weeks of consistent use for patients to feel their effects.28

Fluoride is an effective strategy for at home relief of sensitivity. Sodium fluoride, stannous fluoride, and sodium monofluorophsophate all block dentinal tubules, reducing sensitivity. Prescription fluoride dentifrices and tray application may also be helpful.29

Products containing calcium phosphate technologies are also an option. Amorphous calcium phosphate makes calcium and phosphate ions available in saliva to accelerate remineralization, and may help reduce whitening-induced sensitivity. It is available in a gel and whitening products.29

Casein phosphopeptide-amorphous calcium phosphate (CPP-ACP or Recaldent®) boosts levels of bioavailable calcium and phosphate in saliva without incurring precipitation of calcium salts. A paste containing Recaldent, available through dental offices, can be used to partially occlude tubules. Sometimes, pretreatment with a desensitizing agent will interfere with subsequent bonding. However, a recent study by Borges et al found Recaldent-containing paste did not negatively affect bond strength and, in some instances, improved bond strength.30

Calcium sodium phosphosilicate or NovaMin® can aid in the infiltration and remineralization of dentinal tubules. The silica present in the material performs as a nucleation position for the precipitation of calcium and phosphate.31

Tricalcium phosphate (TCP) is the newest addition to the family of calcium phosphate technologies. Providing a slow release of calcium to the tooth surface, TCP is designed to boost the remineralizing effects of fluoride, which may also decrease sensitivity. It is available in a prescription dentifrice and fluoride varnish.32

IN-OFFICE APPLICATION

A simple in-office therapy may be helpful in addressing sensitivity. A desensitizing prophylaxis paste that uses 8% arginine and calcium carbonate to form plugs of arginine, calcium, phosphate, and carbonate is now available for chairside application. It also has been shown to endure normal pulpal pressure and acid challenges, successfully minimizing dentin fluid flow and, thus, sensitivity,33 without harming bond strength.34

Fluoride varnish allows for the slow and continuous release of fluoride. Varnishes provide a natural resin-based vehicle for fluoride and have the ability to adhere to tooth structure. Calcium fluoride is deposited on the tooth surface, resulting in the formation of fluorapatite. The addition of potassium oxalate causes the formation of acid-resistant calcium oxalate after reaction with the calcium of dentin.35 Extended contact varnish is a photocured fluoride varnish that can be utilized to decrease dentin sensitivity. It consists of a resin-modified glass ionomer that incorporates glycerophosphate with more fluoride release. It also encourages resin tag formation, allowing instantaneous and long-term occlusion of the tubules.

Another varnish combines 5% glutaraldehyde and 35% hydroxyethylmethacrylate (HEMA). The product acts as a biological fixative, and creates a coagulation of plasma proteins in the dentinal tubules, blocking the openings. HEMA can infiltrate acid-etched and moist dentin, and creates precipitation in the tubules. It can reduce sensitivity for at least 3 months.36 These varnishes are compatible with adhesives, cements, and restorative and core build-ups.37

Chlorhexidine-containing varnish forms a mechanical barrier after drying, reducing sensitivity, and provides an antiplaque and antibacterial action.38

Oxalates have been shown to diminish dentinal permeability and block dentinal tubules.39 The oxalate reacts with the calcium ions in dentin to form calcium oxalate crystals in the dentinal tubules and on the surface. However, the effect is reduced over time, as the crystals are removed by brushing and dietary acids. Etching improves the infiltration of calcium oxalate crystals into the dentinal tubules.39

INVASIVE OPTIONS

When less invasive treatment options have been explored, bonding, grafting, and laser use may provide success in addressing sensitivity. Bonding agents can be used to desensitize and bond simultaneously.40 A disadvantage is the need for phosphoric acid prior to placing the bonding agent, which may require the use of anesthesia. An alternative is to use a self-etch adhesive. Another bonding agent blocks dentinal tubules, and contains triclosan to reduce plaque formation.41

Covering any exposed root surface with grafting is another mode of desensitization. This should be considered prior to any bonding techniques because bonded restorations may preclude a successful graft.42 Nd:YAG lasers provide thermal energy absorption on dentin, which may result in occlusion or the narrowing of dentinal tubules.39,43

CONCLUSION

Dentinal hypersensitivity is caused by exposed dentin in which stimuli cause dentin tubular fluid movement that activates nerve fibers to cause pain. The relationship between surface and intratubular precipitation and moderation of sensitivity is not straightforward. It is not the quantity of precipitate, but the quality, density, porosity, depth of penetration, and strength of attachment to the dentin surface that modify the results.40 The effectiveness of treatment is determined by how long the diminution or elimination lasts. Treatment decisions should be based on sensitivity severity and etiology. Some in-office treatments create immediate relief that can be followed with a variety of at-home remedies. A combination of techniques may be warranted to provide long-term relief.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

FIGURE 1. STEVE GSCHMEISSNER/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

FIGURE 2. DR GARY GAUGLER/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

REFERENCES

- Addy M. Dentine hypersensitivity: New perspectives on an old problem. Int Dent J.2002;52:367–375.

- Addy M. Etiology and clinical implications of dentine hypersensitivity. Dent Clin North Am.1990;34:503–514.

- Flyn J, Galloway R, Orchardson R. The incidence of hypersensitive teeth in the West of Scotland. JDent. 1985;13:230–236.

- Addy M, Mostafa P, Newcombe RG. DeAddy M,Mostafa P, Newcombe RG. Define hypersensitivity ingeneral dental population. J Irish Dent Assoc. 1997;43:7–9.

- Dababneh RH, Khouri AT, Addy M. Dentine hypersensitivity—an enigma? A review of terminology, mechanisms, aetiology and management. Br Dent J. 1999;187:606–611.

- Holland GR, Narhi MN, Addy M, Gangarosa L,Orchardson R. Guidelines for the design and conduct of clinical trials on dentine hypersensitivity.J Clin Periodontol. 1997;24:803–813.

- Li Y. Innovations for combating dentin hypersensitivity: current state of the art. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2012;33(Suppl);10–16.

- Kramer IRH. The relationship between dentine sensitivity and movements in the contents of dentinal tubules. Br Dent J. 1955;98:391–392.

- Brännström M. The elicitation of pain in human dentine and pulp by chemical stimuli. Arch OralBiol. 1962;7:59–62.

- Pashley DH. Dentin-predentin complex and its permeability: physiologic overview. J Dent Res.1985;64(Suppl):613–620.

- Magloire H, Maurin JC, Couble ML, et al. Topicalreview. Dental pain and odontoblasts: facts and hypotheses. J Orofac Pain. 2010;24:335–349.

- Camilotti V, Zilly J, Nassar CA, Nassar PO.Desensitizing treatments for dentin hypersensitivity:a randomized, split-mouth clinical trial. Braz OralRes. 2012;26:263–268.

- Chabanski MB, Gillam DG, Bulman JS, NewmanHN. Prevalence of cervical dentine sensitivity in apopulation of patients referred to a specialistPeriodontology Department. J Clin Periodontol.1996;23:989–992.

- Uchida A, Wakano Y, Fukuyama O, Miki T,Iwayama Y, Okada H. Controlled clinical evaluation of a 10% strontium chloride dentifrice in treatment of dentin hypersensitivity following periodontal surgery. J Periodontol. 1980;51:578–581.

- Absi EG, Addy M, Adams D. Dentine hypersensitivity—the effect of toothbrushing and dietary compounds on dentine in vitro: an SEMstudy. J Oral Rehabil. 1992;19:101–110

- Kahler W. The cracked tooth conundrum:terminology, classification, diagnosis, and management. Am J Dent. 2008;21:275–282.

- Bartlett DW. The role of erosion in tooth wear:aetiology, prevention and management. Int Dent J.2005;55(Suppl):277–284.

- Zero DT, Lussi A. Erosion—chemical and biological factors of importance to the dental practitioner. Int Dent J. 2005;55:285–290.

- Lambrechts P, Van Meerbeek B, Perdigão. GladysS, Braem M. Vanherle G. Restorative therapy for the erosive lesion. Eur J Oral Sci 1996;104:229–240.

- Grippo JO. Noncarious cervical lesions: the decision to ignore or restore. J Esthet Dent.1992;4:55–64.

- Abrahamsen TC. The worn dentition—pathognomonic patterns of abrasion and erosion.Int Dent J. 2005;55(Suppl):268–276.

- McIntyre F. Restoring esthetics and anterior guidance in worn anterior teeth. A conservative multidisciplinary approach. J Am Dent Assoc.2000;131:1279–1283.

- Michael JA, Townsend GC, Greenwood LF,Kaidonis JA. Abfraction: separating fact from fiction. Aust Dent J. 2009;54:2–8.

- Lee WC, Eakle WS. Possible role of tensile stress in the etiology of cervical erosive lesions of teeth.J Prosthet Dent. 1984;52:374–380.

- Swift EJ Jr. Tooth sensitivity and whitening. Compend Contin Dent Educ Dent.2005;26(Suppl):4–10.

- Canadian Advisory Board on DentinHypersensitivity. Consensus-based recommendations for the diagnosis and management of dentin hypersensitivity. J Can Dent Assoc. 2003;69:221–226.

- Al-Saud LM, Al-Nahedh HN. Occluding effect ofNd:YAG laser and different dentin desensitizing agents on human dentinal tubules in vitro: a scanning electron microscopy investigation. Oper Dent. 2012;37:340–355.

- Poulsen S, Errboe M, Hovgaard O, WorthingtonHW. Potassium nitrate toothpaste for dentine hypersensitivity. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.2001;2:CD001476.

- Orchardson R, Gillam DG. Managing dentinhypersensitivity. J Dent Assoc. 2006;137: 990–998.

- Borges BC, Souza-Junior EJ, da Costa Gde F, et al.Effect of dentin pre-treatment with a casein phosphopeptide-amorphous calcium phosphate(CPP-ACP) paste on dentin bond strength intridimensional cavities. Acta Odontol Scand.2013;71:271–277.

- Forsback AP, Areva S, Salonen JI. Mineralization of dentin induced by treatment with bioactive glassS53P4 in vitro. Acta Odontol Scand. 2004;62:14–20.

- Karlinsey RL, Mackey AC. Solid-state preparation and dental application of an organically-modifiedcalcium phosphate. J Mater Sci. 2009;44:346–349.

- Panagakos F, Schiff T, Guignon A. Dentinhypersensitivity: effective treatment with an in-office desensitizing paste containing 8% arginine and calcium carbonate. Am J Dent. 2009;22(Suppl):3A–7A.

- García-Godoy A, García-Godoy F. Effect of an 8.0%arginine and calcium carbonate in-office desensitizing paste on the shear bond strength of composites to human dental enamel. Am J Dent.2010;23:324–326.

- Camilotti V, Zilly J, Busato Pdo M, Nassar CA,Nassar PO. Desensitizing treatments for dentin hypersensitivity: a randomized, split-mouth clinical trial. Braz Oral Res. 2012;26:263–268.

- Sethna GD, Prabhulji MLV, Karthikeyan BV.Comparison of two different forms of varnishes inthe treatment of dentine hypersensitivity: a subjectblindrandomized clinical study. Oral Health PrevDent. 2011;9:143–150.

- Dijkman GE, Jongebloed WL, de Vries J, Ogaard B,Arends J. Closing of dentinal tubules by glutaralde hyde treatment, a scanning electron microscopy study. Scand J Dent Res. 1994;102:144–150.

- Sköld-Larsson K, Sollenius O, Petersson LG,Twetman S. Effect of topical applications of a novel chlorhexidine-thymol varnish formula on mutans streptococci and caries development in occlusal fissures of permanent molars. J Clin Dent.2009;20:223–226.

- Lan WH, Lee BS, Liu HC, Lin CP. Morphologicstudy of Nd:YAG laser usage in treatment of dentinalhypersensitivity. J Endod. 2004;30:131–134.

- Ide M, Morel AD, Wilson RF, Ashley FP. Th erole of a dentine-bonding agent in reducing cervical dentine sensitivity. J Clin Periodontol. 1998;25:286–290.

- Yu X, Liang B, Jin X, Fu B, Hannig M. Comparative in vivo study on the desensitizing efficacy of dentin desensitizers and one-bottle self-etching adhesives.Oper Dent. 2010;35:279–286.

- Douglas de Oliveira DW, Marques DP, Aguiar-Cantuária IC, Flecha OD, Gonçalves PF. Effect of surgical defect coverage on cervical dentin hypersensitivity and quality of life. J Periodontol. 2012Aug 24. [Epub ahead of print].

- Orhan K, Aksoy U, Can-Karabulut DC, KalenderA. Low-level laser therapy of dentin hypersensitivity:a short-term clinical trial. Lasers Med Sci. 2011;26:591–598.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. July 2013; 11(7): 54–58.