Treating Patients In Long-Term Care Facilities

Registered dental hygienists in alternative practice provide care to this underserved population via a unique business model.

The recognition of the need for broader delivery of oral care services, which was made public by the Surgeon General’s “Report On Oral Health in America”1 in 2000, could have resulted in more studies of underserved populations. After all, such research is necessary to implement change. However, 15 years later, theses studies have still not been conducted. Though a lack of resources and research was present, an alternative workforce model for disenfranchised populations was created in California. And while preparation for this new provider model began as early as 1979, research on the topic did not commence until 1986. The study, conducted under the California State Office of Statewide Planning, continued with much controversy until 1998, when legislation creating the licensing category called the registered dental hygienist in alternative practice (RDHAP) was passed by the California legislature.2

The recognition of the need for broader delivery of oral care services, which was made public by the Surgeon General’s “Report On Oral Health in America”1 in 2000, could have resulted in more studies of underserved populations. After all, such research is necessary to implement change. However, 15 years later, theses studies have still not been conducted. Though a lack of resources and research was present, an alternative workforce model for disenfranchised populations was created in California. And while preparation for this new provider model began as early as 1979, research on the topic did not commence until 1986. The study, conducted under the California State Office of Statewide Planning, continued with much controversy until 1998, when legislation creating the licensing category called the registered dental hygienist in alternative practice (RDHAP) was passed by the California legislature.2

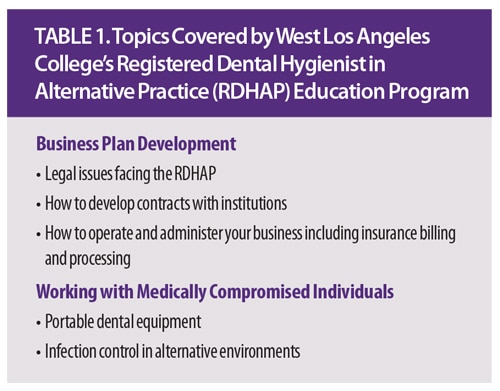

There are specific prelicensing requirements and post-licensing restrictions to RDHAP practice. Training programs weren’t introduced until 2003, with the first established by the Department of Dental Hygiene at West Los Angeles College in Culver City, California. Table 1 provides a list of topics covered by the RDHAP program at this community college. A second, online program was initiated by the California Dental Hygienists’ Association and provided by the University of the Pacific Dugoni School of Dentistry, Division of Special Care Dentistry in San Francisco. For RDHAP licensure, an applicant must be a registered dental hygienist and have successfully completed a bachelor’s degree or its equivalent from an accredited program. Additionally, applicants must complete an accepted RDHAP training program of at least 150 hours; have worked 2,000 hours during the immediately preceding 36 months; and passed a California RDHAP law and ethics exam.3

![]() REGISTERED DENTAL HYGIENIST IN ALTERNATIVE PRACTICE MODELS

REGISTERED DENTAL HYGIENIST IN ALTERNATIVE PRACTICE MODELS

Once all the requirements have been met, RDHAPs can provide care only in residences of the homebound, schools, residential facilities, and other institutions and areas with shortages of dental health professionals identified by the state. Skilled nursing facilities and intermediate care facilities fall under the residential facilities category. In these venues, the RDHAP is technically unsupervised, but legally the RDHAP must have a relationship with a dentist for consultation and referral. Upon creation of this provider, the RDHAP was required to obtain a prescription from a dentist or physician in order to treat patients. Subsequent legislation, however, loosened that restriction by allowing treatment for 2 years, after which a prescription for treatment must be obtained from a dentist or physician. The prescription is then valid for 2 years and there are serious legal consequences for noncompliance. In 2015, legislation was proposed to remove this barrier, but it was unsuccessful.

Currently, there are more than 500 RDHAP graduates. Many RDHAPs maintain practices in long-term care facilities (LTCFs). Some are not practicing, however, for a variety of reasons. Many RDHAPs became educators, while others found the monetary and/or psychosocial price of establishing a practice too high. Some RDHAPs could not find suitable settings in which to provide treatment, while others have lost their practice settings to corporate dental mobile services.

TREATING PATIENTS IN LONG-TERM CARE FACILITIES

Securing a practice facility, even when dental hygiene services do not exist and are clearly needed, is not easy for RDHAPs. An introduction to the facility is usually obtained through the LTCF’s social services director. Once this relationship is established, the RDHAP will receive a survey of the facility and information regarding the residents’ general health. Deciding where the care will be provided, for example in residents’ rooms, in the on-site barber/beauty shop (Figure 1), etc, is the next step. Determining the best work setting can prove challenging in LTCFs.

Ideally, the oral health status of residents is determined. Do they have teeth to clean? Is it possible to assess tissue health? Would oral hygiene services be paid for directly or is there private or public dental insurance? If there is insurance, will it cover the fees of an RDHAP? RDHAPs can be providers for Denti-Cal (California’s dental Medicaid), as well as Delta Dental of California. A recent legislative attempt to require insurance companies that sell policies in California to pay for the provision of services by an RDHAP was unsuccessful.

Once patients have been identified, RDHAPs are permitted to provide prophylaxis, fluoride application, scaling and root planing, and periodontal maintenance. Insurance payment is determined at intervals prescribed by the insurance company. Denti-Cal reimburses a prophylaxis and fluoride application once per year, scaling and root planing every 2 years, and periodontal maintenance quarterly. An RDHAP would also prepare restorative and periodontal charts and make a referral for more serious dental issues.

The business side of providing care can be challenging for the RDHAP, as current software marketed to dental practices must be used and doesn’t always meet practitioner needs. Electronic billing is utilized to request payment for allowable procedures.

MEETING PATIENT CHALLENGES

One barrier to effectively meeting the demands of an institutionalized population is the inconsistency in patients’ availability. Individuals living in LTCFs may not be available as planned due to illness or medical or other appointments within or outside the facility. They may be asleep, be called to a meal, or have unplanned visitors. Also, the planned practice area may be occupied.

Confinement to a bed or a wheelchair makes providing care ergonomically difficult (Figure 2). The patient’s ability to open his or her mouth for extended periods, or at all, may make short appointments necessary. Completing treatment may take several attempts. Some residents may be moderately to highly resistant. Helping patients become more comfortable receiving oral health care services is time consuming.

Patients with dementia are often uncooperative and sometimes paranoid. Trial and error can help RDHAPs create interesting techniques, such as singing to patients, in order to soothe dental anxiety. However, more study is needed on how to more capably deliver essential oral hygiene care services to this population.

Many factors associated with normal aging and infirmity result in LTCF residents presenting with critical need for hygiene care. Older adults often have periodontal diseases and may be prone to caries, both of which can lead to tooth loss. Oral health problems and tooth loss can result in reduced nutritional intake, which exacerbates declining health. Extractions can be life threatening for older adults. Full dentures are often not an option because many residents do not have a mandibular ridge or the tissue is too fragile to comfortably support even the best of dentures. Partial dentures are usually out of reach for LTCF residents, as typically they are not covered by Medicare or Medicaid.

Older adults are at elevated risk of xerostomia due to their medication use, and the resistance of some caregivers to provide daily oral hygiene care compounds this problem (Figure 3). Older adults living in LTCFs typically present with heavy plaque, biofilm, and calculus that are difficult to remove and manage.4

CONCLUSION

Regardless of the challenges incurred when providing care to patients in LTCFs, the rewards can be outstanding. After services are provided, patients are generally happy and more comfortable. RDHAPs also have the satisfaction of preventing additional destruction of the oral cavity. The personal satisfaction of overcoming the aforementioned challenges can be exhilarating.

Are we on the way to making a difference in the oral health of those who are underserved? Time will tell, but many obstacles remain to improving access to care for all Americans.5 Hopefully, our health care system can move toward prevention and identifying the different health needs of a diverse population at all life stages.

REFERENCES

- National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research. Oral Health in America: A Report of the Surgeon General. Available at: nidcr.nih.gov/DataStatistics/SurgeonGeneral/ Documents/ hck1ocv.@ www.surgeon.fullrpt.pdf. Accessed September 24, 2015.

- California Legislative Information. Bill Number: AB 560. Available at: leginfo.ca.gov/pub/97-98/bill/asm/ab_05510600/ab_560_bill_19970912_ enrolled.html. Accessed September 24, 2015.

- California.gov. How to Become a Licensed Dental Auxiliary in California, Registered Dental Hygienist in Alternative Practice (RDHAP). Available at: dhcc.ca.gov/ applicants/becomelicensed_ rdhap.shtml. Accessed September 24, 2015.

- California Dental Hygienists’ Association. California’s Nursing Home Residents—the Dental Iceberg. Available at: cdha.org/portfolio/volume-27-number-1-winter-2012. Accessed September 24, 2015.

- The National Academies Press. Improving Access to Care for Vulnerable and Underserved Populations. Available at: nap.edu/catalog/13116/improving-access-to-oral-health-carefor- vulnerable-and-underserved-populations. Accessed September 24, 2015.

From Perspectives on the Midlevel Practitioner, a supplement to Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. October 2015;12(10):40–43.

REGISTERED DENTAL HYGIENIST IN ALTERNATIVE PRACTICE MODELS

REGISTERED DENTAL HYGIENIST IN ALTERNATIVE PRACTICE MODELS