volkan arslan / iStock / Getty Images Plus

volkan arslan / iStock / Getty Images Plus

Tips for Increasing Keratinized Tissue Width

A wide band of keratinized tissue is protective against future gingival recession.

If left untreated, recession can worsen to the depth of the mucogingival junction and compromise the band of attached, keratinized tissue. The 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions did not numerically specify the amount or thickness of keratinized tissue needed to maintain health. However, tissue that is not inflamed, minimizes further recession, and supports patient comfort, esthetics, and oral hygiene should be considered healthy.1 With this in mind, continued recession is an important driver for treatment.

A wide band of keratinized tissue is protective against future recession, more so in patients with poor oral hygiene who are noncompliant with their recare schedule. This was observed in a split-mouth study, where grafted sites that were not maintained for 5 years were still free of inflammation.2 The amount of keratinized tissue at the initial recare visit was recently considered one of the most important indicators of long-term marginal stability according to a network meta-analysis.3 Keratinized tissue width should therefore be recorded as part of a comprehensive evaluation. This can be manually charted or imported with an intraoral scanner.

Seeking an Increase in Width

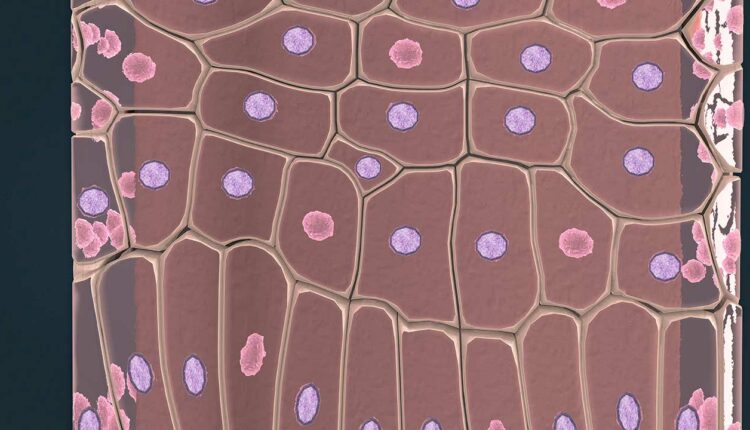

In cases where an increased gain in keratinized tissue width is the desired goal, a free soft tissue autograft or free gingival graft is the preferred treatment.4 A 1-mm to 2-mm thick graft that includes epithelium and connective tissue is harvested from the palate. The donor site is sutured with a hemostatic agent, and a plastic palatal stent is delivered for immediate hemostasis. The graft is then transplanted and secured to a recipient site deficient in attached, keratinized tissue (Figure 1 to Figure 3).

Approximately 44% to 58% shrinkage is expected over the grafted area, mainly in the first 30 days.5 This is commonly performed at low esthetic-risk sites. Nonautogenous materials also work well when there is concern for donor site anatomy, post-operative discomfort, or treatment of multiple defects.6

Patients should not initially anticipate root coverage with this procedure. A phenomenon called creeping attachment does however occur from 1 month to 1 year after surgery. The coronal migration of the gingival sulcus is about 0.8 mm on average and can, in turn, cover exposed roots, especially in areas of narrow, shallow recession.7 Setting appropriate clinical expectations is important. Tooth malposition, high frenum attachment, strong muscle pull, shallow vestibule, and other anatomical factors, can predispose patients to mucogingival problems and negatively affect therapeutic outcomes (Figure 4).

Treatment Planning

The timing of any orthodontic, restorative, and/or implant treatment should be outlined in the treatment planning phase. For example, gingival augmentation may be needed to minimize recession when teeth are moved beyond their normal alveolar housing to establish proper occlusal relations.8

A best-evidence consensus showed that 20% to 25% of patients develop mucogingival defect(s) within 5 years of orthodontic treatment.8 While recession can at least be maintained with regular prophylaxis and proper self-care, patients must understand the treatment objectives and potential complications of interdisciplinary care. They should also be alerted to the added time and expense required at their first appointment.

References

- Cortellini, P, Bissada, NF. Mucogingival conditions in the natural dentition: Narrative review, case definitions, and diagnostic considerations. J Periodontol. 2018;89(Suppl 1):S204–S213.

- Kennedy JE, Bird WC, Palcanis KG, Dorfman HS. A longitudinal evaluation of varying widths of attached gingiva. J Clin Periodontol. 1985;12:667–675.

- Tavelli L, Barootchi S, Cairo F, Rasperini G, Shedden K, Wang HL. The effect of time on root coverage outcomes: a network meta-analysis. J Dent Res. 2019;98:1195–1203.

- Kim DM, Neiva R. Periodontal soft tissue non-root coverage procedures: a systematic review from the AAP regeneration workshop. J Periodontol. 2015;86:S56–S72.

- Silva CO, Ribeiro Edel P, Sallum AW, Tatakis DN. Free gingival grafts: graft shrinkage and donor-site healing in smokers and non-smokers. J Periodontol. 2010;81:692–701.

- Dai A, Huang JP, Ding PH, Chen LL. Long‐term stability of root coverage procedures for single gingival recessions: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Clin Periodontol. 2019;46:572– 585.

- Matter J, Cimasoni G. Creeping attachment after free gingival grafts. J Periodontol. 1976;47:574–579.

- Kao RT, Curtis DA, Kim DM, et al. American Academy of Periodontology best evidence consensus statement on modifying periodontal phenotype in preparation for orthodontic and restorative treatment. J Periodontol. 2020;91:289–298.

This information originally appeared in Saltz AE, Sirois V. The dental hygienist’s role in treating gingival recession. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. May 2022; 20(5)32-35.