SEAN ANTHONY EDDY/E+/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

SEAN ANTHONY EDDY/E+/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

Improving Access to Care for Older Adults

As the number of older adults living in long-term care facilities continues to grow, dental hygienists are well positioned to provide care to this vulnerable population.

It has been 6 years since the New York Times reported on the epidemic of poor oral hygiene and its consequences in long-term care facilities (LTCF).1 Researchers continue to uncover the pathways by which disease is initiated and how it spreads, but we now know that oral disease is the result of an imbalance between the host and its oral microbiome. Left undisrupted, oral organisms will form biofilms, communities of microbes that work together to survive and initiate host responses which often results in disease. Increasingly, we are reminded of the utility of Alfred Fones’, DDS, vision of disease prevention by the removal of plaque on teeth.2

AGING POPULATION

The number of Americans age 65 and older is projected to nearly double from 52 million in 2018 to 95 million by 2060, making their share of the total population rise from 16% to 23%.3 In addition to normal physiologic aging consequences (eg, reduced bone density, impaired immunity, and cognitive decline), older adults experience disease related to chronic conditions (eg, diabetes and cardiovascular disease) and cancers, which often render them frail or functionally dependent. Approximately 75% of those ages 70 to 80 have at least one chronic disease, and 50% have two or more.4 Many older adults take medications that further compromise oral health. Xerostomia affects 40% of patients older than 80, primarily as an adverse effect of medication(s), although it can also result from comorbid conditions such as diabetes, Alzheimer disease, or Parkinson disease.5

According to the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), in 2014, there were 15,600 long-term care facilities (LTCFs) in the US with a total of 1.7 million beds housing approximately 1.4 million residents.5 Additionally, 733,400 individuals reside in assisted living or residential care facilities.4 The Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1987 mandated that the oral health of LTCF residents be maintained, but recent research has shown that most nursing home residents have a host of dental diseases and rarely seek dental care services.6

Older adults are at increased risk for root caries due to root exposure and xerostomia; approximately 50% of those age 75 and older have root caries.7 The most recent data show that 64% of adults age 65 and older have either severe or moderate periodontitis.8 Of particular concern is the role of oral bacteria in the development of hospital-acquired pneumonia (ventilator-associated pneumonia). Mechanical oral hygiene practices reduce the progression or occurrence of respiratory diseases in high-risk older adults in nursing homes or hospitals, preventing the death of about one in 10 elderly nursing home residents from health care–associated pneumonia.9

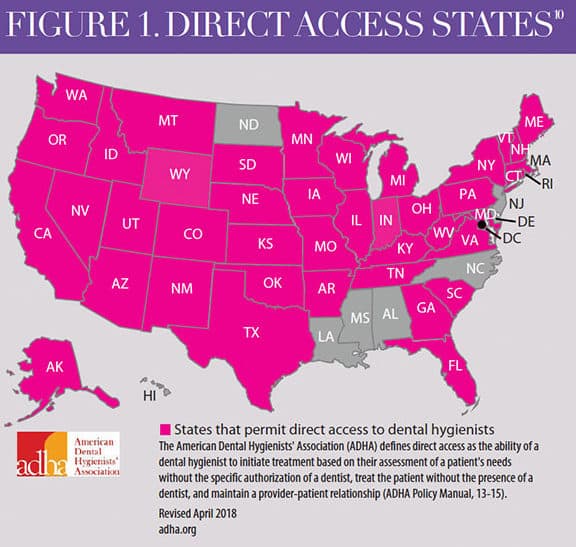

IMPORTANCE OF DIRECT ACCESS

In the US, dental hygienists can legally provide direct access to care in 42 states (Figure 1).10 Direct access “allows a dental hygienist the right to initiate treatment based on his or her assessment of a patient’s needs without the specific authorization of a dentist, treat the patient without the presence of a dentist, and maintain a provider–patient relationship.”10 Other states (eg, New York, Minnesota, and New Mexico) have utilized innovative approaches, such as collaborative practice, which enables a licensed dental hygienist to provide oral health care in a health care facility, program, or nonprofit organization without the patient first being examined by a dentist if the dental hygienist has entered into a collaborative practice agreement with a licensed dentist who authorizes the services.

Dental hygienists can provide oral hygiene services as volunteers, employees, independent contractors, and practice owners (business owners). A dental hygiene business must abide by the laws and regulations of each individual state and is subject to state and local laws and regulations. Providers receive payment for services via private payment; private health/dental insurance; federal and state programs, such as Medicaid; agency funds; facility funds; public grants; and private grants.11 Dental hygienists must receive additional training/credentials in order to provide care in LTCFs and, in some states, may need to have earned a baccalaureate degree.11 Table 1 provides examples of dental hygienists who have created independent businesses.12–14

Dental hygienists can provide oral hygiene services as volunteers, employees, independent contractors, and practice owners (business owners). A dental hygiene business must abide by the laws and regulations of each individual state and is subject to state and local laws and regulations. Providers receive payment for services via private payment; private health/dental insurance; federal and state programs, such as Medicaid; agency funds; facility funds; public grants; and private grants.11 Dental hygienists must receive additional training/credentials in order to provide care in LTCFs and, in some states, may need to have earned a baccalaureate degree.11 Table 1 provides examples of dental hygienists who have created independent businesses.12–14

While many dental hygienists may not be prepared to open their own dental hygiene business, all can volunteer their services at LTCFs to provide basic oral hygiene care, such as toothbrushing, prophylaxis, education on storing prostheses, and teaching nursing staff about the basics of oral hygiene. Table 2 lists free resources to help dental hygienists to begin implementing such programs.15–17

CONCLUSION

In the coming years, due to the benefits of fluoridation, increased education on prevention of oral diseases, and availability professional dental care, oral health professionals will need to care for many more older adults with more of their natural teeth—some of whom will be frail or functionally dependent and living in residential facilities. State legislatures have responded by broadening scopes of practice that permit dental hygienists to use their knowledge to alleviate the burden on LTCF staff. As Alfred C. Fones, DDS, stated: “It is primarily to this important work… that the dental hygienist is called … the greatest service she can perform is the persistent education of the public in mouth hygiene and the allied branches of general hygiene.”17

TABLE 1. EXAMPLES OF DENTAL HYGIENISTS WHO HAVE CREATED INDEPENDENT BUSINESSES

ELDERCARE DENTAL HYGIENE SERVICES

Established in 2000 by Anita Rodriguez, RDH, BSDH, ElderCare Dental Hygiene Services contracts with dental hygienists in Washington State to provide dental hygiene services to older adults and people with special needs in a variety of settings, including long-term residential facilities, adult family homes, group homes, private residences, and senior centers. Rodriguez also mentors dental hygienists interested in following in her footsteps via the Alliance of Dental Hygiene Practitioners (alliancerdhpractitioners.org).12

LIMITED ACCESS PERMIT

In Montana, dental hygienists can obtain a Limited Access Permit that allows “licensed dental hygienists to provide dental hygiene preventive services without the prior authorization or presence of a licensed dentist in a designated public setting.”13 Many dental hygienists have created their own businesses providing dental hygiene care in various facilities and share their success stories on the state’s American Dental Hygienists’ Association website (montanadha.org/limited-access-permit-lap-2/limited-access-permit-lap/).14

TABLE 2. FREE AND EASILY ACCESSIBLE RESOURCES TO HELP DENTAL HYGIENISTS SUPPORT THE ORAL HEALTH OF LONG-TERM CARE FACILITY RESIDENTS

NATIONAL INTERPROFESSIONAL INITIATIVE ON ORAL HEALTH (NIIOH)

A national effort to increase oral health in education and practice of primary care clinicians, jointly funded by the DentaQuest Foundation, Washington Dental Service Foundation, and the REACH Healthcare Foundation, NIIOH provides funding to organizations that are integrating oral health into primary care education and practice. Resources including videos, PowerPoint presentations, informative links, and other documents, are available on its website at: niioh.org/resources.15

SMILES FOR LIFE

A national oral health curriculum created by the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine offers eight modules that cover oral health issues across the lifespan, including geriatric oral health. Endorsed by the American Dental Association, the organization offers an online curriculum that health care providers can complete. Educators/trainers can download slides and speaker notes for in-person training at: smilesforlifeoralhealth.org/buildcontent.aspx.16

GRANT, FUNDING, AND ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

- National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research

nidcr.nih.gov/health-info/for-older-adults - American Dental Hygienists’ Association Community Service Grants

adha.org/ioh-community-service-grants-main

- Dental Trade Alliance Foundation Scholarships and Grants

dentaltradealliance.org/foundation - American Association of Public Health Dentistry Foundation

aaphd.org/foundation

REFERENCES

- Saint Louis C. In nursing homes, an epidemic of poor dental hygiene. New York Times. August 4, 2013.

- Connecticut Dental Hygienists’ Association. History and Mission. Available at: cdha-rdh.com/about-us. Accessed October 15, 2019.

- Population Reference Bureau. Aging in the United States. Available at: prb.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/aging-us-population-bulletin-1.pdf. Accessed October 15, 2019.

- Yellowitz JA, Schneiderman MT. Elder’s oral health crisis. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2014;14 (Suppl):191–200.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Nursing Home Care. Available at: cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/nursing-home-care.htm. Accessed October 15, 2019.

- Katz RV, Smith BJ, Berkey DB, Guset A, O’Connor MP. Defining oral neglect in institutionalized elderly. J Am Dent Assoc. 2010;141:433–440.

- Gregory D, Hyde S. Root caries in older adults. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2015;43:439–445.

- Eke PI, Dye BA, Wei L, et al. Prevalence of periodontitis in adults in the United States: 2009 and 2010. J Dent Res. 2012; 91:914–920.

- Rosenblum R. Oral hygiene can reduce the incidence of and death resulting from pneumonia and respiratory tract infection. J Am Dent Assoc. 2010:141:1117 –1118.

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association. Direct Access. Available at: adha.org/direct-access. Accessed October 15, 2019.

- Naughton D. Expanding oral care opportunities: direct access care provided by dental hygienists in the United States. J Evid Based Pract. 2014;14(Suppl):171–182.

- Eldercare Dental Hygiene Services. Available at: https://eldercaredentalhygieneservices.com/. Accessed October 15, 2019.

- Montana Dental Hygienists’ Association. Limited Access Permit. Available at: montanadha.org/limited-access-permit-lap-2/. Accessed October 15, 2019.

- Montana Dental Hygienists’ Association. Success Stories. Available at: montanadha.org/limited-access-permit-lap-2/limited-access-permit-lap/. Accessed October 15, 2019.

- National Professional Interprofessional Initiative on Oral Health. Available at: niioh.org/content/about-us. Accessed October 15, 2019.

- Smiles for Life. Available at: https://smilesforlifeoralhealth.org/buildcontent.aspx?tut=555&pagekey=62948&cbreceipt=0. Accessed October 15, 2019.

- Fones AC. Mouth Hygiene. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1934.

From Perspectives on the Midlevel Practitioner, a supplement to Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. October 2019;6(11):14,16—18.