MONKEYBUSINESSIMAGES / ISTOCK / GETTY IMAGES PLUS

MONKEYBUSINESSIMAGES / ISTOCK / GETTY IMAGES PLUS

Benefits of Medical-Dental Integration

Both patients and clinicians stand to gain under this model of care.

The United States Preventive Services Task Force recommends that children receive fluoride varnish applications when the first primary tooth erupts, usually at age 6 months to 1 year.1 The American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry suggests that first permanent molars receive dental sealants shortly after eruption, at about age 6.2 Unfortunately, in 2020, only about 52% of children enrolled in Medicaid received any kind of dental services.3 Indeed, in that same year, only 40,758 (1.99%) Medicaid enrollees under the age of 1 received a preventive dental treatment. In addition, only 957,692 (11.8%) of children ages 6 to 9 covered by Medicaid received dental sealants.

One of the primary reasons for this is that so few dentists will treat patients covered by Medicaid; while 38% is the national estimate, the number is highly variable from state to state and dependent on the methodology used to determine the estimate.4,5 On the other hand, primary care providers—including pediatricians, family physicians, advanced registered nurse practitioners, and physician assistants—do serve these vulnerable patients.6

The purpose of this paper is to suggest that the implementation of dental hygienists working in primary care practices is a smart strategy to improve access to dental care for patients covered by Medicaid and other vulnerable patients. It would also provide significant employment opportunities for dental hygienists.

The implementation of dental hygienists working in primary care practices is a smart strategy to improve access to dental care for patients

covered by Medicaid and other vulnerable patients.

Definition

Medical-dental collaboration and integration are not new to the oral health space. It is important, however, to distinguish between collaboration and integration.7 “Collaboration” refers to primary care and oral healthcare team members working together to improve the health outcomes of their patients; a good example is the primary care clinic staff providing preventive dental services and referring patients to a dental home.

“Integration” refers to oral health services provided by a dental team member within and/or embedded into the primary care medical team. This type of medical-dental integration is not a new concept. A number of states have dental practice acts that allow these kinds of activities by dental hygienists.8–10

Medical-Dental Integration In Action

Supported in part by a Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) Oral Health Workforce grant to the Florida Department of Health, a medical-dental integration project was implemented in Florida. Dental hygienists were placed in the pediatric clinic of a federally qualified health center (FQHC). Anecdotal evidence from several other FQHCs in Florida suggested this model would be a success; however, quantifying the results so they could be shared in addition to supporting the recommendation that other FQHCs should implement medical-dental integration were the goals.

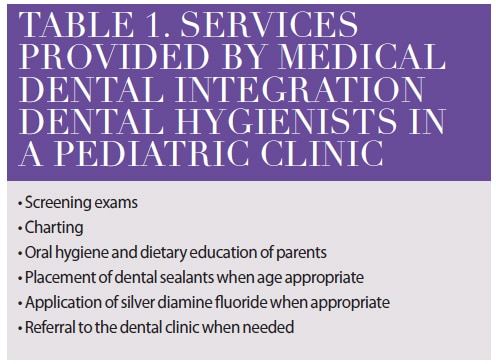

We placed two medical-dental integration (MDI) dental hygienists in two pediatric clinics of the FQHC; another pediatric clinics served as a control site. Table 1 lists the services provided by the MDI hygienists.

The results were not surprising. Children seen by the MDI hygienist received fluoride varnish applications and dental sealants earlier than children who were simply referred to the dental clinic by the pediatric clinic. What was surprising was that the dental clinic failure/no-show rate for children referred to the dental clinic was less than half of those children simply referred by the pediatric clinic staff. A detailed report with supporting data is in preparation for journal submission. Several papers that describe best practices in implementing medical-dental integration programs have been published.11–15

Medical-dental integration provides new career opportunities and pathways for dental hygienists to work at the top of their scope of practice.

Barriers to Implementation

Some barriers do exist to medical-dental integration that can be relatively easy to overcome. Sharing of health information rarely occurs between medical and dental providers without a fully integrated medical and dental electronic health record. Primary care practitioners traditionally see the mouth as the property of dentists and may be uncomfortable or uninterested in adding another procedure to a busy practice model. Medical and dental care are seen by the public/patients as separate. Limited oral health education is provided to medical professionals. However, good efforts have been made to overcome these barriers.

One of the primary barriers to medical-dental integration is restrictive dental practice acts that prevent dental hygienists from being employed and supervised by a primary care practice.16,17 This model works in Florida FQHCs because the dental hygienist is under general supervision of a dentist within the FQHC system and because the FQHC can bill for the dental hygienist’s services.

This is why the efforts of the American Dental Hygienists’ Association (ADHA) to implement direct access for dental hygienists should be broadly supported. According to the ADHA, direct access refers to the ability of dental hygienists to:18

- Initiate treatment based on their assessment of a patient’s needs without the specific authorization of a dentist

- Treat the patient without the presence of a dentist

- Maintain a provider-patient relationship

![table 1]() Conclusions

Conclusions

Lack of access to quality dental care is a critical problem for many individuals, especially low-income populations and people of color. These oral health inequities have serious consequences including interfering with school learning and performance and negatively impacting the oral health-systemic health link. Medical-dental integration is one way to improve access to preventive dental services and referrals to a dental home. In addition, medical-dental integration provides new career opportunities and pathways for dental hygienists to work at the top of their scope of practice. Medical-dental integration is good for both patients and dental hygienists.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Kim Herremans, RDH, MS, executive director of the Greater Tampa Bay Oral Health Collaborative, who has been implementing medical-dental integration projects in Florida FQHCs for years and who was the inspiration for this project. Also, thanks to the staff of Central Florida Health Center for allowing us to implement this project, especially its first MDI dental hygienist, Jennifer Reichert, RDH, for her valuable ideas during implementation. Funded in part from the Florida Department of Health, Dental Public Health Program with Health Resources and Services Administration funding for Grants to States to Support Oral Health Workforce Activities. The grant number is: 6 T12HP31863‐03‐01.

References

- United States Preventive Services Task Force. Prevention of Dental Caries in Children Younger Than 5 Years: Screening and Interventions.

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry and American Dental Association. Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guideline for the Use of Pit-and-Fissure Sealants.

- Medicaid.gov. Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment.

- Bucci M. A Lack of awareness impacts the care of medicaid dental patients.

- Vujicic M, Nasseh K, Fosse C. Dentist participation in medicaid: how should it be measured? does it matter?

- Robertson L. Medicaid’s Doctor Participation Rates.

- Pourat N, Martinez AE, Haley LA, Crall JJ. Colocation does not equal integration: identifying and measuring best practices in primary care integration of children’s oral health services in health centers. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2020;20:101469.

- Braun PA, Cusick A. Collaboration between medical providers and dental hygienists in pediatric health care. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2016;16(Suppl):59–67.

- Braun PA, Kahl S, Ellison MC, Ling S, Widmer-Racich K, Daley MF. Feasibility of colocating dental hygienists into medical practices. J Public Health Dent. 2013;73:187–194.

- Atchison KA, et al. Bridging the dental-medical divide: case studies integrating oral health care and primary health care. J Am Dent Assoc. 2018;149:850–858.

- Prasad M. Integration of oral health into primary health care: a systematic review. J Family Med Prim Care. 2019;8:1838–1845.

- Emami E, Couturier Y, Girard F, Torrie J. Integration of oral health into primary health care organization in Cree Communities: a workshop summary. J Can Dent Assoc. 2016;82:30.

- Harnagea H, Lamothe L, Couturier Y, et al. From theoretical concepts to policies and applied programmes: the landscape of integration of oral health in primary care. BMC Oral Health. 2018;18:23.

- Simon L, Tobey M, Wilson M. Feasibility of integrating a dental hygienist into an inpatient medical team for patients with diabetes mellitus. J Public Health Dent. 2019; 79:188–192.

- Langelier M, Moore J, Baker BK, Mertz E. Case studies of 8 federally qualified health centers: strategies to integrate oral health with primary care.

- Pew Charitable Trusts. When Regulations Block Access to Oral Health Care, Children at Risk Suffer.

- Close K, Rozier RG, Zeldin LP, Gilbert AR. Barriers to the adoption and implementation of preventive dental services in primary medical care. Pediatrics. 2010;125:509–517.

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association. Direct Access.

From Perspectives on the Midlevel Practitioner, a supplement to Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. October 2022;9(10):6-8.