Zygomatic Implants for Patients With Complex Dental Conditions

Special considerations must be made to maintain the health of this type of dental implant.

This course was published in the January/February 2024 issue and expires January/February 2027. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

AGD Subject Code: 690

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Identify the characteristics and advantages of zygomatic implants as an alternative to conventional endosteal implants.

- Note the criteria for selecting patients suitable for zygomatic implants.

- Discuss the evaluation criteria, surgical approaches, and hygiene protocols for zygomatic implants, emphasizing the role of dental hygienists in preventing peri-mucositis, periimplantitis, and managing biofilm around these unique implants.

While endosteal implants generally exhibit a high success rate, they may not always be a suitable treatment option. The success rates for dental endosteal implants in addressing edentulism are 97% at 10 years and 75% at 20 years.1 In 1998, Per-Ingvar Brånemark, MD, PhD — the father of modern implantology — and his team explored the potential of zygomatic implants as an alternative for patients ineligible for conventional dental implants due to severe alveolar resorption in edentulous ridges or alterations in alveolar ridges resulting from surgical resection in patients with cancer.

Zygomatic implants are designed to provide a stable anchor for prosthesis retention using the zygomatic bone, more commonly referred to as a cheekbone. The quadrangular zygomatic bone, with a bone density of 98%, has proven to offer both quality and quantity as a favorable site for implant placement.2,3

Scientific literature reports an overall survival rate of 96.7% at 12 years for zygomatic implants.4 In an edentulous oral cavity, the success rate for zygomatic implants (96.7% at 12 years) is comparable to endosteal implants (97% at 10 years).5 When comparing a zygomatic implant to an endosteal dental alveolar implant, the quality and quantity of the zygomatic bones are more dense than the alveolar bone, which may influence the zygomatic implant success rate.

Patient Selection Criteria

Zygomatic implants are indicated for several patient types, including patients who present with inadequate alveolar bone, have history of previously failed conventional dental alveolar implants, have undergone maxillary trauma or resection, and who present with specific congenital deformities.

Inadequate alveolar bone may be caused by tooth loss. Alveolar bone will remodel and resorb after a tooth is extracted. The pattern of alveolar bone resorption in the maxilla occurs in a three-dimensional pattern with the bone changing shape in a posterior, medial, and superior aspects, compromising the shape of dental alveolar ridge, which results in a smaller maxilla.9,10 This bone pattern, known as severe dental atrophy, is defined as an alveolar ridge less than 4 mm.11 In absence of disease, the mean alveolar bone height ranges from 18 to 21 mm.12

Head and neck cancers — the most common cause of resection of the maxillary or mandibular arch — are another indication for zygomatic implant therapy. Oral pathology associated with maxillary resection includes osteosarcoma, squamous cell sarcoma, adenoid cystic carcinoma, and mixed salivary carcinoma.13,14 Unfortunately, patients who undergo maxillary resections lose dental masticatory function and facial support. Zygomatic implants can restore masticatory function and improve facial esthetics by supporting a dental prosthesis that restores facial contour and function.

Specific dental conditions associated with facial development, such as cleft palate and ectodermal dysplasia, may also need a zygomatic implant-supported dental prostheses. Patients with cleft palate who are classified as edentulous with a history of cleft palate (EHCP) usually have a severely resorbed maxillary ridge with significant scar tissue and irregular palate anatomy. A patient with EHCP may not be a candidate for dental alveolar implants (without extensive grafting) and this clinical presentation may be suitable for zygomatic implants.15

Ectodermal dysplasia is a diverse group of inherited disorders that impacts structures related to the ectodermal layer such as hair, nails, teeth, and sweat glands. With a prevalence of one in 100,000 live births, ectodermal dysplasia may result in inadequate hard and soft tissue in the oral and maxillofacial region.16 Individuals with ectodermal dysplasia may have anodontia (absence of all teeth), hypodontia, or oligodontia.

Hypodontia refers to the absence of less than six teeth and oligodontia means the absence of six or more teeth. Dental alveolar implants may not be indicated for patients with ectodermal dysplasia if the alveolar bone quantity and quality are inadequate. Zygomatic implant placement, however, is possible without bone grafting procedures.17

A retrospective study of nine patients aged 21 to 56 with severe atrophic maxilla due to ectodermal dysplasia revealed the successful use of zygomatic implants. The treatment significantly improved the subjects’ quality of life, with no reported complications.17

Evaluation criteria used to select patients indicated for zygomatic implants consists of a medical history, radiographic series, and clinical examination. Initially, panoramic radiography is taken for the initial patient consultation to discuss zygomatic implants and demonstrate the patient’s lack of alveolar bone.5

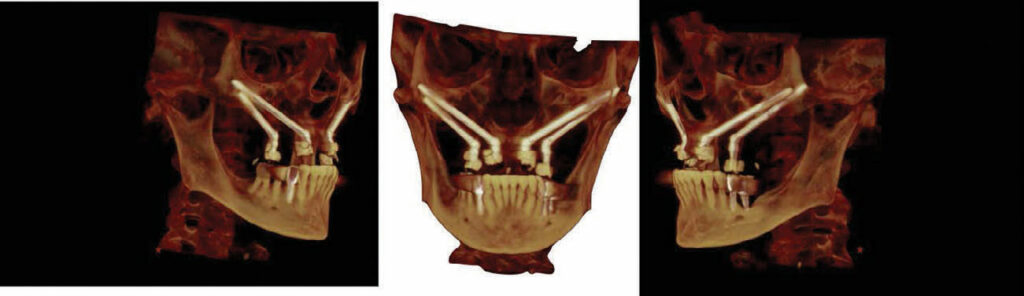

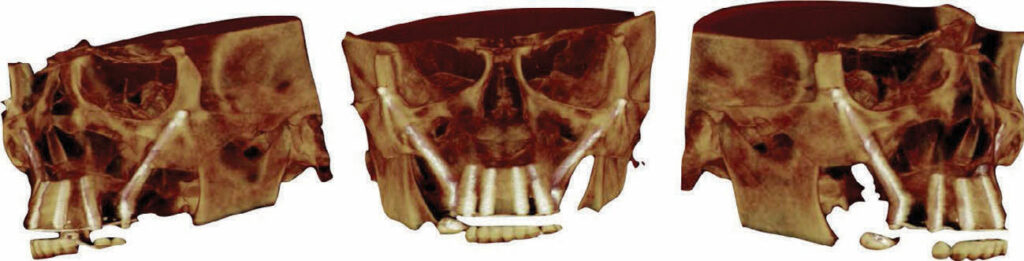

Cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) is required for zygomatic implants. The CBCT uses a cone X-ray beam that produces 3D images of the anatomy and potential implant sites. Once CBCT images are obtained, the dental provider determines the site for the least traumatic implant osteotomy.

Aparicio18 has developed a classification system called the Zygoma Anatomy-Guided Approach (ZAGA), which categorizes the anatomic variations in maxillary anatomy and how they relate to the zygomatic arch. This results in a surgical approach adapting the osteotomy to the patient’s anatomy.

Zygomatic implant maxillary site locations can be from the region of the lateral to the first or second molar area. They may pass through the maxillary sinus depending on the ZAGA classification. Patients considering a zygomatic implant may need a sinus lift procedure. Zygomatic implants can reestablish masticatory function and facial contour by supporting a fixed dental prosthesis. They have a high success rate and are well tolerated by many patients who are not candidates for endosteal dental alveolar implants. In general, four zygomatic implants can stabilize an entire maxillary prosthesis.18

Zygomatic implants can fail, however.4 Related complications include poor selection of osteotomy location, osseointegration failure, oroantral infections, maxillary sinusitis, or inflammation of the maxillary sinus lining, or rhinosinusitis. Chronic rhinosinusitis symptoms include nasal airway obstruction, mucous secretions, headache, facial pain, and anosmia.19 Fortunately, many zygomatic implant complication can be managed by improved oral hygiene and antibiotics.

Placing an endosteal implant is easier compared to the complex surgical placement required for zygomatic implants. Additionally, when endosteal implants fail, the implant is easily retrieved and the alveolar site can be augmented with bone grafting materials so the implant can be replaced. Failing zygomatic implants may be saved with oral debridement and antibiotic therapy, but other zygomatic implants failures may need surgical intervention.

Role of the Dental Hygienist

The dental hygienist’s educational training and clinical experiences are well suited to understanding the management of biofilm around dental alveolar implants. This knowledge can be translated to the management of zygomatic implants in the effort to prevent peri-mucositis and peri-implantitis. The most common culprits behind zygomatic peri-implantitis are Gram-negative bacteria such as Porphyromonas gingivalis, Prevotella intermedia, Treponema denticola, Prevotella nigrescens, Fusobacterium nucleatum, and Peptostreptococcus spp.20

Zygomatic implants are immediately loaded at the time of surgical implant placement. Patients are placed on a post-surgical regime of antibiotics, applying ice for 20 minutes on and 10 minutes off for 24 hours, and sleeping with their heads elevated to control swelling. Nutritional recommendations include a soft diet and frequent hydration. Implementing sinus precaution procedures including refraining from blowing the nose for 3 weeks, and decreasing antra pressure by opening the mouth in the event of a sneeze. Rinsing with salt water twice a day for 2 weeks is also recommended.

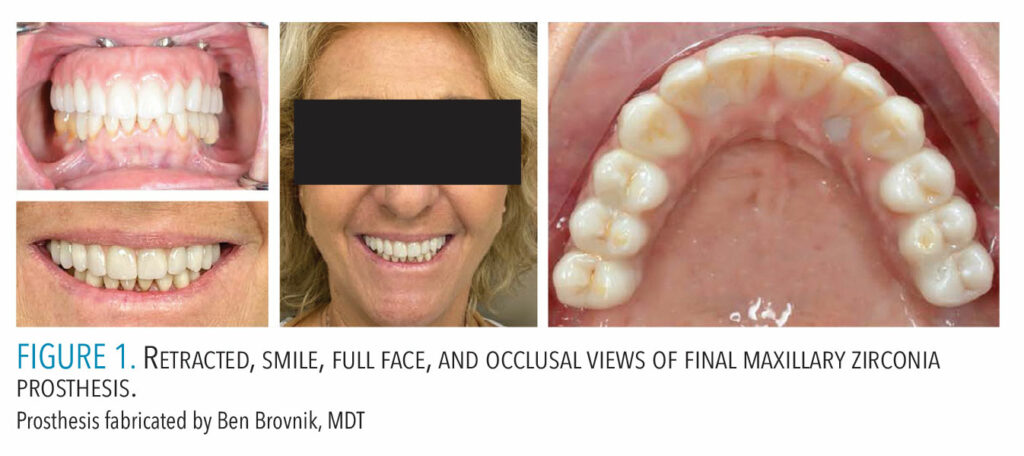

Zygomatic implants are longer than dental alveolar implants, ranging in length from 30 to 52.5 mm.21 The head of the zygomatic implant is designed to allow the dental prosthesis to be attached at a 45° or 55° angle to the long axis of the implant (Figures 1 to 3).21 The length and trajectory of the zygomatic implants create a problematic situation for biofilm control. Due to the length of zygomatic implants and the penetration through the antrum and oral mucosal tissues, the threads of the implant are often exposed. This can be reduced with improved surgical technique and the use of immediate load buccal fat pad.21 A zygomatic implant with clinical visualization with seven threads is considered normal.5 The threads provide a protected area for biofilm accumulation.

FRANK TUMINELLI, DMD, FACP. SURGICAL PHOTOS COURTESY OF JAY NEUGARTEN

The immediate load provisional fixed prosthesis which is not removed unless there is implant or tissue complication during the first 6 months and prior to final restoration fabrication may complicate biofilm removal.21 Therefore, patients must be taught strategies for self-care to clean around the prosthesis. Unlike dental alveolar implants, zygomatic implants’ length, design, angulation, exposure of the threads, and the fact the prosthesis cannot be removed require a stringent protocol to manage the biofilm.22

FRANK TUMINELLI, DMD, FACP.

SURGICAL PHOTOS COURTESY OF JAY NEUGARTEN

The standard evaluation of a zygomatic implant includes absence of pain and mobility, lack of any sinus pathologies, mild recession of the peri-implant soft tissue exposing up to seven implant threads, and the correct balance of forces on the dental prosthesis to the implant fixture.5

The removal of supragingival and subgingival biofilm from zygomatic implants should be done with an air abrasive device and glycine or erythritol powder with careful angulation of the tip.23 Patients should be on a 3-month recare schedule to prevent calculus formation.22 Typically, biofilm and food debris accumulation are removed during a hygiene appointment.

Both glycine and erythritol powders are biocompatible with oral tissues, prosthesis, and implant. They will not cause corrosive or mechanical wear and they may reduce the presence of P. gingivalis in patients with periodontitis.23 If necessary, the dental hygienist should use hand scalers (eg, titanium scalers) biocompatible around implants.

Prosthesis fabricated by Ben Brovnik, MDT

Frank Tuminelli, DMD, FACP. Surgical photos courtesy of Jay Neugarten

Other adjunctive measures may include end-tuft brushes, in-office oral irrigation, and at-home irrigation or water flosser on low-medium power.22 Patients should also use an over the counter antimicrobial mouthrinse twice a day. Magnunson et al24 revealed that using a water flosser compared to floss reduced bleeding around implants. The long-term use of chlorhexidine mouthrinse may contribute to the corrosiveness around dental implants, therefore, it should only be used in the short term.25 In the operatory, polishing with a low abrasive paste and a rubber cup should be done on the dental prosthesis.

Conclusion

Motivating and educating patients on their self-care are critical for those with zygomatic implants. Dental hygienists are knowledgeable in preventing peri-mucositis and peri-implantitis and in recognizing sinus complications, thus, they should be prepared to help patients with zygomatic implants achieve and maintain oral health.

References

-

- Gosain, Arun K. M.D.; Song, Liansheng D.D.S., M.S.; Capel, Christopher C. M.D.; Corrao, Marlo A. B.S.; Lim, Tae-Hong Ph.D.. Biomechanical and Histologic Alteration of Facial Recipient Bone after Reconstruction with Autogenous Bone Grafts and Alloplastic Implants: A 1-Year Study. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery 101(6):p 1561-1571, May 1998.

- da Hora Sales, P. H., Gomes, M. V. S. W., de Oliveira-Neto, O. B., de Lima, F. J. C., & Leão, J. C. (2020). Quality assessment of systematic re- views regarding the effectiveness of zygomatic implants: An over- view of systematic reviews. Medicina Oral Patología Oral Y Cirugia Bucal, 25, e541–e548. https://doi.org/葖.4317/medoral.23569

- Vrielinck, L., Moreno-Rabie, C., Schepers, S., Van Eyken, P., Coucke, W., & Politis, C. (2022). Peri-zygomatic infection associated with zygomatic implants: A retrospective longitudinal cohort study. Clinical Oral Implants Research, 33, 405–412. https://doi.org/葖.1111/clr.13900

- Aparicio, C., Manresa, C., Francisco, K., Claros, P., Alández, J., González‐Martín, O., & Albrektsson, T. (2014). Zygomatic implants: indications, techniques and outcomes, and the zygomatic success code. Periodontology 2000, 66(1), 41-58.

- Ramezanzade, S., Yates, J., Tuminelli, F. J., Keyhan, S. O., Yousefi, P., & Lopez-Lopez, J. (2021). Zygomatic implants placed in atrophic maxilla: an overview of current systematic reviews and meta-analysis. Maxillofacial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 43(1), 1-15.

- Neugarten, J., Tuminelli, F. J., & Walter, L. (2017). Two Bilateral Zygomatic Implants Placed and Immediately Loaded: A Retrospective Chart Review with Up-to-54-Month Follow-up. International Journal of Oral & Maxillofacial Implants, 32(6).

- Tallgren A. The continuing reduction of the residual alveolar ridges in complete dentures wearers: A mixed-longitudinal study covering 25 years. J Prosthet Dent. 2003; 89 (5):427-35

- Branemark Pl, Grondahl K, Worthington P. The challenge of the severely resorbed maxilla. In : Darle C editor. Ossesintgration and Autogenous Onlay Bone Grafts: reconstruction of the edentulous atrophic maxilla. 2001. p.2-6.

- Aparicio C, Ouazzani W, Garcia R, Arevalo X, Muela R, Fortes V. A prospective clinical study on titanium implants in the zygomatic arch for prosthetic rehabilitation of the atrophic edentulous maxilla with a follow-up of 6 months to 5 years. Clinical Implant Dentistry and Related Research. 2006;8(3):114-122. doi:10.1111/j.1708-8208.2006.00009.x

- Zhang W, Skrypczak A, Weltman R. Anterior maxilla alveolar ridge dimension and morphology measurement by cone beam computerized tomography (CBCT) for immediate implant treatment planning. BMC Oral Health. 2015 Jun 10;15:65. doi: 10.1186/s12903-015- 0055-1. PMID: 26059796; PMCID: PMC4460662.

- Tuminelli F, Balshi T. Zygomatic Implants: position statement of the American College of Prosthodontics. 2016.

- Misch C, Polido W.A “Graft Less” Approach for Dental Implant Placement in Posterior Edentulous Sites. In J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2019 Nov;39 (6):771-9.

- Leven J, Ali R, Butterworth CJ. Zygomatic implant-supported prosthodontic rehabilitation of edentulous patients with a history of cleft palate: A clinical report. The Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry. 2022;127(5):684-688. doi:10.1016/j.prosdent.2020.10.026

- Chrcanovic.B.R. Dental implants in patients with ectodermal dysplasia: A systematic review. Journal of cranio-maxillo-facial surgery : official publication of the European Association for Cranio-Maxillo-Facial Surgery. 8 (2018): 1211-1217 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ꪗ

- Goker F, Grecchi E, Mancini EG, Del Fabbro M, Grecchi F. Zygomatic implant survival in 9 ectodermal dysplasia patients with 3.5‐ to 7‐year follow‐up. Oral Diseases. 2020;26(8):1803- 1809. doi:10.1111/odi.13505

- Aparicio C. The zygoma anatomy-guided approach: Zaga—a patient-specific therapy concept for the rehabilitation of the atrophic maxilla. Zygomatic Implants. 2020:63-85. doi:10.1007/⻊-3-030-29264_䁳_䁳

- Kumar H., Jain R., Douglas R.G., Tawhai M.H. Airflow in the Human Nasal Passage and Sinuses of Chronic Rhinosinusitis Subjects. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0156379. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156379

- Rakašević, D., Lazić, Z., Rakonjac, B., Soldatović, I., Janković, S., Magić, M., & Aleksić, Z. (2016). Efficiency of photodynamic therapy in the treatment of peri-implantitis: A three- month randomized controlled clinical trial. Srpski arhiv za celokupno lekarstvo, 144(9-10), 478-484.

- Ramezanzade, S., Yates, J., Tuminelli, F.J. et al. Zygomatic implants placed in atrophic maxilla: an overview of current systematic reviews and meta-analysis. Maxillofac Plast Reconstr Surg 43, 1 (2021). https://doi.org/葖.1186/s40902-020-00286-z

- Felice, P., Bertacci, A., Bonifazi, L., Karaban, M., Canullo, L., Pistilli, R., … & Barausse, C. (2021). A proposed protocol for ordinary and extraordinary hygienic maintenance in different implant prosthetic scenarios. Applied Sciences, 11(7), 2957.

- Shrivastava D, Natoli V, Srivastava KC, Alzoubi IA, Nagy AI, Hamza MO, Al-Johani K, Alam MK, Khurshid Z. Novel Approach to Dental Biofilm Management through Guided Biofilm Therapy (GBT): A Review. Microorganisms. 2021 Sep 16;9(9):1966. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms9091966. PMID: 34576863; PMCID: PMC8468826.

- Magnuson, B., Harsono, M., Stark, PC., Lyle, D, Kugel, G, Perry R. Comparison of the effect of two interdental cleaning devices around implants on the reduction of bleeding: a 30-day randomized clinical trial. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2013 Nov-Dec;34 Spec No8:2-7.PMID: 24568169.

- Wingrove SS. Peri-Implant Therapy for the Dental Hygienist. 2nd ed. New Jersey: Wiley Blackwell;2022.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. Jan/Feb 2024; 22(1):32-35