What Oral Health Professionals Need to Know About Hypothyroidism

This autoimmune disease presents critical challenges and opportunities for dental providers to aid in early detection and ensure safe, effective care.

This course was published in the July/August 2025 issue and expires August 2028. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

AGD Subject Code: 149

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Define hypothyroidism.

- Discuss the different types of hypothyroidism.

- Identify considerations for dental treatment among patients with hypothyroidism.

As of 2022, hypothyroidism affected approximately 11.7% of the United States population, representing around 30 million people ages 18 and older.1 This is an increase in cases from the previous estimates (gathered from data collected between 1988-1994), which placed the incidence of hypothyroidism at 4.6%.1 The percentage of untreated hypothyroidism cases also increased from 11.8% to 14.4% between 2012 and 2019.1 The increase in prevalence may be attributed to the rise in cases of subclinical hypothyroidism (mild-thyroid failure) and the wait-and-see approach to diagnosis and treatment. Dental professionals need to be aware of the signs and symptoms of hypothyroidism to assist with diagnosis and prevent complications that may arise from treating patients with uncontrolled hypothyroidism.2

Hypothyroidism is a condition in which the thyroid gland doesn’t produce enough thyroid hormones. These hormones regulate the body’s metabolism (ie, how it uses energy). The thyroid gland is a small butterfly-shaped gland located in the front of the neck and is a significant part of the endocrine system. It uses iodine to produce the thyroid hormones thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3), which impact many physiological functions.3

The thyroid gland and associated hormones are responsible for regulation (eg, mood, metabolism, temperature, immunity); development and growth (eg, brain, tissues, organs); nutrient metabolism (eg, carbohydrates, proteins, fats); and cardiovascular function (eg, heart rate, strength of cardiac contractions, blood pressure).4 The hypothalamus and pituitary gland regulate thyroid hormone production in a feedback loop known as the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis. The pituitary gland then signals the thyroid gland to produce hormones.5

Primary and Secondary Hypothyroidism

Hypothyroidism is more prevalent among women than men and affects white individuals more than Black or Hispanic populations.3 There are two major categories of hypothyroidism: primary and secondary.1,6 Primary hypothyroidism occurs when the thyroid gland is unable to produce enough thyroid hormones. Secondary hypothyroidism occurs when the thyroid gland function is normal, yet the pituitary gland or hypothalamus has pathology that affects the messages sent to the thyroid gland to signal the production of thyroid hormones. Secondary hypothyroidism may be caused by pituitary tumors, compression of the hypothalamus due to tumors, radiation of the brain, and drugs including dopamine, prednisone, or opioids.1,6

![]() Etiology and Pathophysiology

Etiology and Pathophysiology

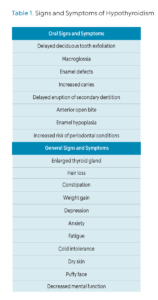

Hypothyroidism is the second most common endocrine disorder, after diabetes. Table 1 lists the systemic signs and symptoms of hypothyroidism.1,2,6,7 In extreme cases, myxedema (severe form of hypothyroidism), coma, and death can occur. Patients with myxedema present with an altered mental state, thermoregulation problems leading to hypothermia, and a precipitating event, such as infection or myocardial infarction, that triggers the myxedema.8 Hypothyroidism also affects cardiac function, including cardiac contractions, blood pressure, heart rhythm, and peripheral vascular resistance.9

The most common cause of hypothyroidism is an iodine deficiency. Hashimoto autoimmune disease is the most common cause of primary hypothyroidism in developed countries.1,3,6-10 Autoimmune thyroid disease, such as Hashimoto disease, is associated with increased diabetes mellitus type 1 and type 2 due to abnormal glucose metabolism.10

Autoimmunity to the thyroid gland occurs when antibodies to thyroid antigens are present.11 Other causes of primary hypothyroidism are thyroiditis, radiation on the thyroid gland, certain prescription drugs used to treat ventricular arrhythmias (eg, amiodarone), and medications used to treat manias and bipolar conditions (eg, lithium), congenital hypothyroidism, and surgical removal of all or part of the thyroid gland due to thyroid cancer.2,3,6

Thyroiditis

Thyroiditis is the inflammation of the thyroid gland. Subacute thyroiditis, also called deQuervain thyroiditis, is believed to be caused by a viral infection that affects the thyroid gland. Subacute thyroiditis usually follows an infection such as influenza, upper respiratory tract infection, COVID-19, or mumps.12,13

The thyroid gland becomes inflamed and can be painful during the acute phase. This type of thyroiditis will usually resolve independently, but in some cases, it becomes chronic.17 Post-partum thyroiditis occurs within the first year of giving birth. Post-partum thyroiditis usually resolves within 12 to 18 months, but as with subacute thyroiditis, this form of hypothyroidism can also become chronic.19 Thyroiditis can lead to hypothyroidism by inflammation in the gland, pushing the stored thyroid hormone out of the gland and into the bloodstream. An increase in thyroid hormone can be initially found in the blood, but this condition eventually leads to hypothyroidism.4

Congenital Hypothyroidism

Congenital hypothyroidism is primarily caused by abnormal development of the thyroid gland and, when left untreated, leads to many oral signs and symptoms, along with systemic changes including short stature, puffy face, weight gain, stubby hands, underdeveloped muscle tone, pale skin, hoarse voice, broad flattened nose, widely spaced eyes, underdeveloped bones, and intellectual disabilities.2,10

Newborn screening for congenital hypothyroidism is necessary due to the absence of signs of hypothyroidism at birth. The screening should be completed when the infant is 3 days old.5,10,20 Many infants are discharged earlier than this, so in the United States, –the screening is required to be completed before infants leave the hospital. The screening consists of a simple blood test to check the levels of T4 and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH). When T4 and TSH levels are found to be low, treatment with levothyroxine is recommended. If levothyroxine therapy is started quickly after birth, it can prevent oral manifestations along with developmental delays and permanent intellectual disabilities.20 Global neonatal screening is needed for thyroid disease to avoid delayed diagnosis, especially when screening is easy, low cost, and the benefits are immense.10

The first step to diagnosing hypothyroidism is testing the TSH level in the blood.8,21 If TSH is low, this usually indicates hypothyroidism.4 Blood tests for T4, T3, and thyroid antibody tests are also used to diagnose hyperthyroidism. Imaging, such as ultrasound and thyroid scans, can be used to assess thyroid health.21 Early diagnosis of hypothyroidism is important for preventing other health complications.

Treatment Options

The most common treatment for hypothyroidism is thyroid hormone replacement with levothyroxine (LT4).1,2,3,6,7,14,15 Before 1970, therapy consisted of combination therapy supplementation of synthetic forms of both LT4 and LT3. It was during the 1970s that treatment transitioned to monotherapy with synthetic LT4.15 Treatment with synthetic LT4 allows for precise hormone dosing tailored to each patient’s specific needs, ensuring optimal thyroid hormone levels.16 The dosage of levothyroxine given is determined by patients’ body weight, gender, age, and current thyroid hormone levels. Dosing is very sensitive, and a blood test to measure TSH levels is recommended 6 weeks after switching to a new brand of levothyroxine, when transitioning to a generic brand, or going back and forth between brands.15

Oral Implications

Hypothyroidism has many oral signs and symptoms, such as delayed deciduous teeth exfoliation, delayed eruption of secondary teeth, macroglossia, anterior open-bite, enamel defects, enamel hypoplasia, increased incidence of caries, and increased incidence of periodontal disease. Patients with congenital hypothyroidism are the most affected by these oral signs and symptoms.2,17,18 Some studies also show a possible correlation between hypothyroidism and the increased incidence of oral lichen planus (OLP).14,19

OLP is a chronic inflammatory condition that presents as white lacey patches (that cannot be wiped away with gauze), open sores, and red, inflamed tissues affecting oral surfaces, including the buccal mucosa, palate, tongue, and gingival tissues.14,19,23 OLP can cause oral pain, discomfort, and sensitivity to spicy, acidic, or hot food and beverages.20

While its etiology is unknown, OLP is considered an autoimmune-related disorder. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the prevalence of autoimmune disorders in patients with OLP showed comorbidity between OLP and autoimmune thyroid disease, specifically hypothyroidism and Hashimoto thyroiditis.19 More than 150 studies, representing 23,327 patients, were included in the systematic review and meta-analysis. It concluded that the risk of developing thyroid disease was almost double in patients with OLP than the general population, and Hashimoto thyroiditis and hypothyroidism were the most prevalent types.

At all initial and recare appointments, a thorough medical history should be taken, including questions regarding the common symptoms of thyroid disease and a comprehensive head and neck exam should be performed. The TSH levels of patients with OLP should be periodically tested due to the high incidence of comorbidity of thyroid disease and OLP. Dental professionals should also refer any patient with OLP to an endocrinologist if thyroid disease is suspected.19

Responsibilities of Dental Providers

Dental providers are in a unique position to detect thyroid abnormalities. Observation and palpation of the thyroid gland through the dental head and neck examination can lead to discovering abnormalities in the size of the gland.21 A thorough medical history can reveal signs and symptoms of thyroid disease.18 If undiagnosed thyroid disease is suspected, the dental professional should defer treatment and refer to an endocrinologist for evaluation and diagnosis.2

Complications can arise from providing dental treatment to patients with uncontrolled hypothyroid due to increased bleeding and delayed wound healing, leading to a higher risk of systemic infection. A cross-sectional study determined that dental students had a good knowledge of the function and disorders of the thyroid gland.2 Still, they lacked awareness of the biochemical mechanism behind thyroid disease and how this can affect the treatment plan for their patients.17

Dental professionals need to become more educated on how thyroid disease can affect dental treatment. Patients can be at risk for health complications when dental professionals are unaware of the signs and symptoms of untreated thyroid disease.2,17

Dental Treatment Considerations

Managing the dental treatment of patients with hypothyroidism can be complex. Preventive measures such as maintaining oral hygiene, placing pit and fissure sealants, regular fluoride exposure, and restorative measures, including caries restorations and extractions, are key.2 Stress management procedures should also be utilized during the dental appointment.18

When considering dental treatment for children with hypothyroidism, referrals should be given to orthodontists to maintain space for secondary tooth eruption and corrective treatment as needed. Pit and fissure sealants should be utilized to prevent decay. It may be necessary to refer patients with macroglossia to an oral surgeon for evaluation and treatment.2

If OLP is observed, education and management are necessary. Patients with undiagnosed OLP should be referred to their primary care physician or an oral pathologist. Treatment considerations should include patient education, stress management, and gentle care of the affected tissues. Patients should be advised to observe if any food or beverages exacerbate their symptoms and to avoid them in the future. Questions on what patients use for oral self-care should be asked, and recommendations to avoid products that contain harsh ingredients (eg, alcohol, cinnamon, and some mint flavorings) should be given. Corticosteroids may be prescribed by the dentist or physician if deemed necessary to manage the lesions.20

Conclusion

There is no cure for hypothyroidism, but treatment with levothyroxine is safe and effective at preventing symptoms. Dental professionals are responsible for noticing the signs and symptoms of hypothyroidism to help facilitate diagnosis and prevent complications that may arise from treating a patient with uncontrolled hypothyroidism. A thorough health history and head and neck exam should be performed at each dental hygiene appointment. Communication with other health specialists is crucial for properly treating patients with hypothyroidism. A referral to an endocrinologist should be given if undiagnosed hypothyroidism is suspected.

References

- Wyne KL, Nair L, Schneiderman CP, et al. Hypothyroidism prevalence in the united states: a retrospective study combining National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey and Claims Data, 2009–2019. J Endocr Soc. 2022;7:bvac172.

- Nagar K, Sujatha GP, Shubha C, Lingappa A. Oral physician: A portal to systemic health through oral health – A case of hypothyroidism and review of literature. International Journal of Oral Health Sciences. 2018;8(1):39-46.

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Hypothyroidism (Underactive Thyroid). Available at niddk.nih.gov/health-information/endocrine-diseases/hypothyroidism. Accessed June 3, 2025.

- Venkatesh Babu N, Patel P. Oral health status of children suffering from thyroid disorders. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2016;34:139.

- Feldt-Rasmussen U, Effraimidis G, Klose M. The hypothalamus-pituitary-thyroid (HPT)-axis and its role in physiology and pathophysiology of other hypothalamus-pituitary functions. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2021;525:111173.

- Patil N, Rehman A, Jialal I. Hypothyroidism. Available at ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519536. Accessed June 3, 2025.

- Chiovato L, Magri F, Carlé A. Hypothyroidism in context: where we’ve been and where we’re going. Adv Ther. 2019;36:47-58.

- Wiersinga WM. Myxedema and Coma (Severe Hypothyroidism). Available at ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/books/NBK279007. Accessed June 3, 2025.

- Udovcic M, Pena RH, Patham B, Tabatabai L, Kansara A. Hypothyroidism and the heart. Methodist DeBakey Cardiovasc J. 2017;13:55-59.

- Kawicka A, Regulska-Ilow B, Regulska-Ilow B. Metabolic disorders and nutritional status in autoimmune thyroid diseases. Postepy Hig Med Dosw (Online). 2015:69:80-90.

- Lee HJ, Li CW, Hammerstad SS, Stefan M, Tomer Y. Immunogenetics of autoimmune thyroid diseases: A comprehensive review. J Autoimmun. 2015;64:82-90.

- UCLA Health. What Is Subacute Thyroiditis? Available at uclahealth.org/medical-services/surgery/endocrine-surgery/patient-resources/patient-education/endocrine-surgery-encyclopedia/subacute-thyroiditis. Accessed June 3, 2025.

- Naguib R. Potential relationships between COVID-19 and the thyroid gland: an update. J Int Med Res. 2022;50:3000605221082898.

- Garcia-Pola MJ, Llorente-Pendás S, Seoane-Romero JM, Berasaluce MJ, García-Martín JM. Thyroid disease and oral lichen planus as comorbidity: a prospective case-control study. Dermatology. 2016;232:214-219.

- Mateo RCI, Hennessey JV. Thyroxine and treatment of hypothyroidism: seven decades of experience. Endocrine. 2019;66:10-17.

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Thyroid Tests. Available at .niddk.nih.gov/health-information/diagnostic-tests/thyroid. Accessed June 3, 2025.

- Mahajan S, Kapoor HS. Knowledge and attitude of dental students toward thyroid gland and its disorders: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Oral Health Sciences. 2022;12(2):79-85.

- Dudhia SB, Dudhia BB. Undetected hypothyroidism: A rare dental diagnosis. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2014;18:315-319.

- De Porras-Carrique T, Ramos-García P, Aguilar-Diosdado M, Warnakulasuriya S, González-Moles MÁ. Autoimmune disorders in oral lichen planus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Dis. 2023;29:1382-1394.

- Mayo Clinic. Oral Lichen Planus – Symptoms and Causes. Available at mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/oral-lichen-planus/symptoms-causes/syc-20350869. Accessed June 3, 2025.

- Pocket Dentistry. Comprehensive Head and Neck Exam. Available at pocketdentistry.com/comprehensive-head-and-neck-exam. Accessed June 3, 2025.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. July/August 2025; 23(4):40-45.