Update on Hepatitis B

While the incidence of hepatitis B infection is declining, the health risks associated with this “silent killer” remain significant.

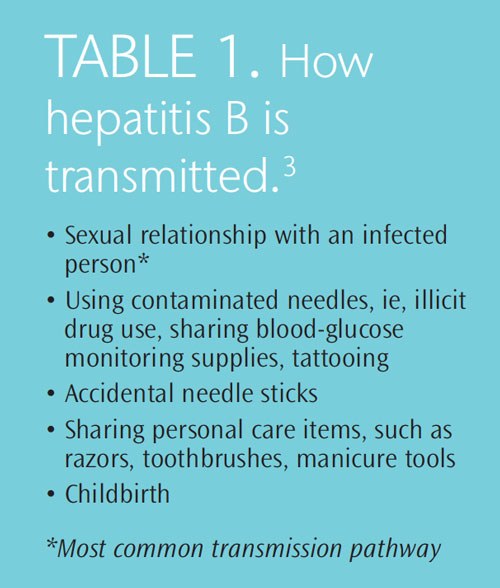

The hepatitis B virus (HBV) affects more than 1 million people in the United States and between 350 million and 400 million worldwide.1 HBV is transmitted through contact with bodily fluids—including blood, semen, and vaginal secretions—of an HBV-infected individual (Table 1), and causes inflammation of the liver. It is part of the viral hepatitis family that includes hepatitis A, C, D, E, F, and G.2 HBV initially causes an acute infection, which most people overcome. However, between 5% and 10% of those with acute infections develop a chronic HBV infection, which means the virus has been present in the body for more than 6 months.3 For children under 5, the risk of developing a chronic infection after exposure to HBV is much greater. Among babies exposed during childbirth, the rate of chronic infection is nearly 90%.3 The good news, according to the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), is that acute HBV infections have declined approximately 85% from the early 1990s to 2009.4

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Most adults with acute HBV infection exhibit symptoms (Table 2); approximately 30% experience an asymptomatic infection where no outward signs are experienced. 3,5 Children often do not display any signs of the infection. HBV can be devastating for those who develop a chronic infection that goes untreated, which is why it is often called the “silent killer.” Symptoms in people unaware of their infection may not appear for 20 years to 30 years.5 During this time, significant liver damage can occur, including cirrhosis and liver cancer. Approximately 15% to 25% of those with chronic HBV infection develop serious liver disease that leads to significant morbidity and mortality.5

TREATMENT

Acute HBV infection is typically treated with bed rest. Those who seek medical care within 2 weeks of their exposure to the virus can receive the HBV vaccine and an injection of hepatitis immune globulin to help kill the infection.3 People recovering from acute HBV infection need to pay special attention to safeguarding the health of their liver by avoiding substances that are harmful to the liver, such as alcohol and over-the-counter medications like acetaminophen.

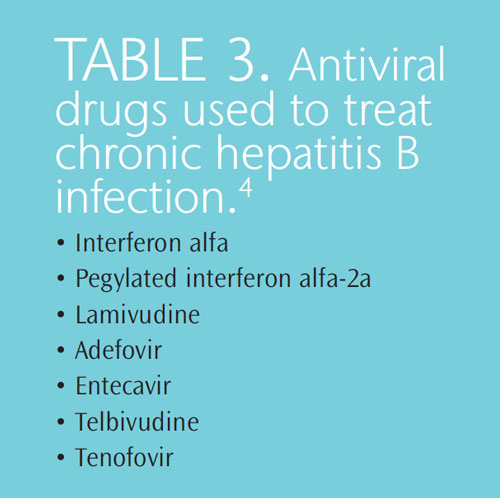

Antiviral drugs are often used to treat HBV infection (Table 3).1 They are designed to reduce the levels of HBV in the blood. The CDC reports that these medications are continually improving, and are effective in reducing HBV DNA viral loads within weeks to months after the antiviral drug regimen begins.6 Therefore, this evidence shows that these drugs can effectively slow and sometimes halt the progression of chronic HBV infection.1

VACCINATION

The HBV vaccine was first introduced in 1982, and since then, the rate of new HBV infections in the United States has sharply declined.4 During the 1980s, there were approximately 200,000 new cases of HBV in the US each year, whereas today, about 43,000 new cases are diagnosed annually.4

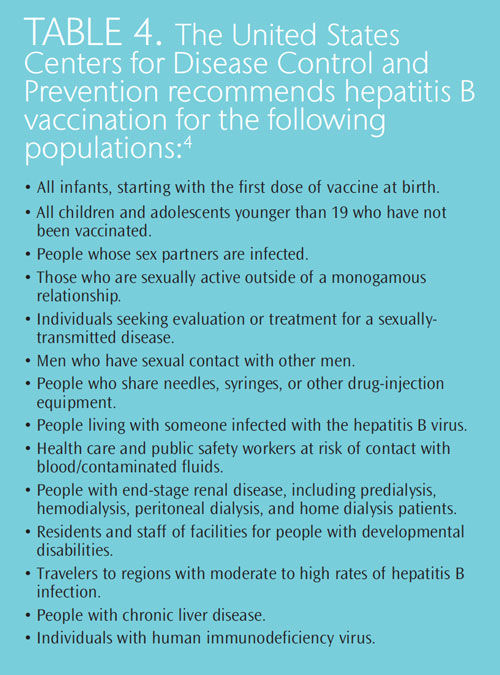

The HBV vaccine is 90% effective and is recommended for all health care providers, including dental professionals, as well a variety of other populations (see Table 4 for a complete list).4 The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) requires that employers offer, at no charge, the HBV vaccination to all health care workers. Those who refuse must sign a declination waiver indicating that it was offered, explained, and subsequently refused.6,7 Health care workers should follow the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices guidelines.8 Individuals need to be titer tested following their vaccination to ensure they are protected. The immunization is a series of three injections and there is no current recommendation for a booster. OSHA also requires that post-exposure management be provided to all exposed employees.

NEW CDC GUIDELINES

In July 2012, the CDC released new guidelines on the management of HBV and infected health care providers and students.6 They provide an update of the previous guidelines that were published in 1991 in an effort to prevent the transmission of HBV and the human immunodeficiency virus from health care professionals to patients. This update was provided because the understanding of the epidemiology of HBV and its management has greatly improved over the past 22 years. The guidelines emphasize the same assertion made in 1991—health care workers and students should not be precluded from patient care due to their HBV status. The CDC asserts that as long as standard infection control precautions are stringently followed, the presence of HBV infection in a medical or dental professional does not require any additional safety measures or exclusion of duties.

One significant change in the new guidelines is the elimination of the recommendation that health care workers and students pre-notify patients of their HBV status. This stipulation was deemed unnecessary due to the very low risk of transmission in both medical and dental settings.9 The last known case of HBV transmission from a dental professional to a patient occurred in 1987, and there has been only one reported case of transmission in a surgical setting since 1994.6,10

The other changes in the guidelines relate to how HBV infectivity is measured, specific recommendations for monitoring those health care professionals who require oversight, and an adjustment of the HBV DNA serum levels that are deemed safe for practice.6

STANDARD PRECAUTIONS

Standard precautions are effective in reducing the risk of transmission of bloodborne pathogens, as well as other pathogenic organisms. Dental professionals are obligated to perform standard infection control precautions when treating all patients in order for risk reduction to be effective.

These precautions require that all health and dental professionals receive the HBV vaccination series. Standard precautions also include appropriate work practice and engineering controls, such as the implementation of effective hand hygiene procedures using either soap and water or alcohol-based hand rubs; the donning of gloves, gowns, masks, and protective eyewear during the provision of patient care when bodily fluids may be exchanged; and the safe handling of sharp objects.11–13 The CDC first published infection control guidelines in 1986 and 1993, which addressed clusters of HBV transmission from infected dental professionals to patients in the 1970s and 1980s. The most current dental infection control guidelines were published in 2003.11

CONCLUSION

While the incidence of HBV infection continues to decline, dental professionals must be sure to protect themselves and their patients from inadvertent transmission. The implementation of standard infection control precautions are designed to significantly reduce the risk of any viral transmission, and should, therefore, be followed diligently by health care providers. Dental professionals are also encouraged to consistently review the literature to remain current on new developments or recommendations.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

PHOTOCREDIT : DR LINDA STANNARD, UCT/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

REFERENCES

- Dienstag JL. Hepatitis B virus infection. J N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1486–1500.

- A.D.A.M. Medical Encyclopedia [CD-ROM]. 10th ed. Atlanta: A.D.A.M.Education; 2013.

- Web MD. Hepatitis B Health Center. Available at: www.webmd.com/hepatitis/hepb-guide/default.htm. Accessed February 13, 2013.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Overview of hepatitis B.Available at: www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/B/bFAQ.htm. Accessed February 13,2013.

- Office of Population Affairs, Department of Health and HumanServices. Hepatitis B Fact Sheet. Available at: www.hhs.gov/ opa/reproductive-health/stis/hepatitis-b/. Accessed February 13, 2013.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated CDC recommendations for the management of hepatitis B virus-infected health-care providers and students. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2012;6:1–12.

- United States Department of Labor. Occupational Safety and HealthAdministration. Regulations. Available at: www.osha.gov/pls/oshaweb/owadisp.show_document?p_table=STANDARDS&p_id=10051. Accessed February 12, 2013.

- CDC. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. Available at:www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/index.html. Accessed February 12, 2013.

- Lohr KN. Rating the strength of scientific evidence: relevance for quality improvement programs. Int J Qual Health Care. 2004;16:9–18.

- Younai FS. Health care-associated transmission of hepatitis B and C viruses in dental care (dentistry). Clin Liver Dis. 2010;14:93–104.

- Kohn WG, Collins AS, Cleveland JL, Harte JA, Eklund KJ, Malvitz DM,CDC. Guidelines for infection control in dental health-care settings—2003. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2003;19:1–61.

- Boylard EA, Tablan OC, Williams WW, Pearson ML, Shapiron CN,Deitchman SD, Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee.Guideline for infection control in health care personnel, 1998. Am J Infection Control. 1998:26:289–354.

- Siegel JD, Rhinehart E, Jackson M, Chiarello L; Health Care InfectionControl Practices Advisory Committee. 2007 Guideline for Isolation Precautions: Preventing Transmission of Infectious Agents in Health Care Settings. Am J Infect Control. 2007;35(Suppl):S65–164.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. March 2013; 11(3): 40, 42, 44.