Troubling Tobacco Trends

Educate your patients about the significant health risks posed by the latest nicotine products.

But regardless of the grave side effects, limits on advertising and the wide adoption by cities and states of smoke-free legislation, Americans spend about $90 billion on tobacco products each year.2,3 Tobacco manufacturers have remained successful by adapting existing tobacco products and introducing new ones. Consumers are often unfamiliar with the actual nicotine content of these products (Table 1) and their potential for inducing addiction. Dental hygienists need to educate their patients about these products and their associated health risks.

LOW-TAR CIGARETTES

In response to the results published in the 1964 Surgeon General’s report, tobacco companies modified their products by adding filters, ventilation holes, and additives, and then marketing them as less harmful than regular cigarettes.4 These cigarettes were introduced as “low-yield” or “light.”5 This turned out to be a hugely successful strategy, as the number of Americans who smoked low-tar cigarettes increased from 1.5 million in 1967 to more than 40 million in 2005.3

Early studies, based on machine-measured yield tests of tar and nicotine, predicted lung cancer death rates would fall. Unfortunately, these tests failed to mimic the effects of inhaling tobacco and they were easily manipulated by tobacco companies.5 Low-tar cigarettes contain 0.6 mg to 1.0 mg of nicotine, while regular cigarettes include between 1.2 mg and 1.4 mg. However, low-tar versions release the same amount of carcinogens as regular cigarettes.

Smoking “light” cigarettes elevates the risks of developing cancers and other diseases because the intake of tar and nicotine is increased when smokers inhale more smoke per puff, inhale more often, and smoke cigarettes to a shorter butt length.5 In addition, a false sense of reduced risk may cause some smokers to continue smoking low-tar cigarettes instead of quitting.

CIGARS

When cigarette smoking declined in the 1990s, a significant increase in cigar use occurred.6 Glamorized by tobacco companies and the movie industry, cigars became an acceptable part of social events. Many users consider cigar smoking less harmful because they smoke fewer cigars than they would cigarettes, and they don’t inhale. One cigar, however, contains higher levels of carcinogenic nitrosamines, toxins, and tar, and up to 20 times more tobacco than one cigarette. The nicotine content varies significantly, from 5.9 mg to 335.2 mg per cigar.6

All cigar smokers directly expose their lips, mouths, tongues, throats, and larynges to tobacco smoke. The pH of cigar smoke can reach 8.5. This means it is absorbed through the oral mucosa easier than cigarette smoke, thus, increasing cigar smokers’ risk of oral and esophageal cancers.7

Nonetheless, in 1997 American consumers bought more than 5 billion cigars, and sales have continued to climb.7 Cigar smoking has also become trendy among young adults. According to the 2002 National Youth Tobacco Survey, cigars were the second most popular tobacco product among young people.

NEW SMOKELESS TOBACCO PRODUCTS

The tobacco industry is expanding its consumer base by introducing new dissolvable, spitless tobacco products. These products are marketed as less harmful because they contain less nicotine, no tar, and no carbon monoxide. Unfortunately, users are still exposed to nitrosamines and nicotine.

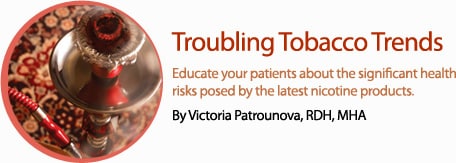

The discreet size of these new tobacco products allows their use in smoke-free areas and many smokers start using them in conjunction with cigarette smoking, thus increasing their total nicotine intake. Other products feature unique candy-like flavorings and packaging similar to mints, which may attract young people. In 2009, R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co introduced several new smokeless, flavored tobacco products with varying nicotine contents. Camel Sticks contain the highest amount of nicotine (3.1 mg), and one stick lasts about 20 minutes to 30 minutes. Camel Orbs have a nicotine content of 1.0 mg per orb and last about 10 minutes to 15 minutes. Available in mint and cinammon flavors, Orbs have a high level of absorbable nicotine and deliver a jolt of the addictive substance because of their alkalinity.9 Camel Strips have the lowest nicotine content among the latest smokeless products at 0.6 mg of nicotine per strip, and they only last for 2 minutes to 3 minutes.

R.J. Reynolds was severely criticized for packaging tobacco orbs in a container that is similar to Tic Tac breath mints (Figure 1). Their resemblance to candy and gum poses a threat to unsuspecting consumers and there has been one reported case of an infant accidentally ingesting Camel Orbs.10

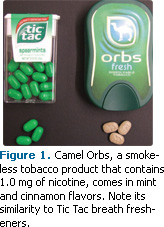

Camel Snus was introduced in 2006 (Figure 2). The newest version contains 8.0 mg of nicotine per pouch. Snus, which is increasingly popular in the United States, is similar to Swedish moist snuff with about 50% moisture content. Snus is placed between the cheek and upper lip for about 30 minutes and can cause leukoplakia and gingival recession in the area. Nicotine is absorbed through the oral mucosa without chewing or spitting.

Swedish snus contains a lower content of nitrosamine and other carcinogenic substances than snuff.11 While snus has not been associated with oral or lung cancer, a 2007 study found that the risk of pancreatic cancer in snus users was nearly double compared to those who had never smoked.12

Sweden has the highest number of snus users but one of the lowest rates of cigarette smoking and smoking-related deaths among men. It is the only country to meet the World Health Organization’s target of 20% for adult smoking prevalence.13 Further research is necessary to see if snus may be helpful as a tobacco cessation aid.

IMPORTED TOBACCO PRODUCTS

Many forms of flavored tobacco, such as clove cigarettes, bidis, and shisha, have become popular in recent years.14 Clove cigarettes (called kreteks) from Indonesia and bidis from India might be perceived as “herbal,” “natural,” and safe by young people, but they contain tobacco and deliver more nicotine, tar, and carbon monoxide than regular cigarettes.

Shisha, a fruit-flavored tobacco (Figure 3), is used when hookah smoking. A hookah is a type of water pipe with a smoke chamber, bowl, pipe, and hose (Figure 4). Hookah smoking originated in Persia and India and is a popular social activity in the Middle East. Many believe the water filters out all toxins, and therefore the smoke is less irritating and less harmful to the throat and respiratory tract than cigarette smoke.15 Unfortunately, this is not the case, and hookah smokers are exposed to carbon monoxide, heavy metals, tar, and carcinogens.

One session of hookah smoking usually lasts an hour, increasing users’ exposure to nictone and carcinogens.16 Lung and oral cancer, other lung diseases, and periodontal diseases have all been linked to hookah smoking.15 There are an estimated 300 hookah cafés and lounges in the United States, and this number is expected to grow.16

ELECTRONIC CIGARETTES

Electronic cigarette manufacturers claim their products are an alternative to patches and gum during the smoking cessation process. They look like cigarettes, cigars, or pipes and come in flavors such as mint or chocolate. E-cigarettes are composed of three parts: a recharge able battery-operated heating element, a replaceable cartridge, and an atomizer (Figure 5). The heated atomizer converts the contents of the cartridge or “smoke juice” into a vapor that is inhaled. This vapor contains nicotine and other chemicals.

E-cigarettes have not been evaluated by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and the levels of nicotine or other chemicals they contain are unknown. The FDA is concerned that e-cigarettes are sold to young people and do not contain “health warnings comparable to FDA approved nicotine replacement products or conventional cigarettes.” The administration is developing a strategy to regulate this emerging class of products.17

TOBACCO CESSATION PRODUCTS

In 2008 an updated set of clinical guidelines was released by the National Cancer Institute and the US Department of Health and Human Services. The main goal was to provide clinicians with effective tools for tobacco dependence counseling and medication options for patients who use tobacco.18

Research shows that tobacco cessation medications are more effective in combination with counseling. Bupropion SR, nicotine gum, lozenges, inhalers, nasal sprays and patches, and varenicline were approved by the FDA to assist cigarette smokers with tobacco cessation. Nicotine replacement products, such as nicotine gum, patches, and lozenges, are available over-the-counter whereas nicotine nasal sprays, oral inhalers, bupropion, and varenicline are available by prescription only. Neither bupropion nor varenicline are recommended for people under 18 years of age.19 Both medications have specific contraindications, warnings, and side effects,19 and patients who take them should be monitored by health care professionals. Further research is needed to determine the effectiveness of these medications for smokeless tobacco users.19

There are many free resources available to assist in quitting tobacco, including: online quit plans, support groups, phone-based services , and even free applications for smartphones. Despite all the help available, it often takes multiple attempts to succeed in giving up tobacco.

CONCLUSION

In response to the decreasing number of adult cigarette smokers, the tobacco industry is trying to attract young people with “healthier” tobacco products in hopes of expanding the market. None of these products is free of carcinogens, and most still contain enough nicotine to pose an addiction risk. All of them, except snus, increase users’ risk of oral cancer.

The challenge for dental professionals is to identify users of these products as they may lack the typical signs of tobacco use, such as tobacco stains and odor, and the appearance of tissue changes in unusual areas, such as under the upper lip. Clinicians can play a critical role in educating patients about the nicotine content and potential harmful effects of these new tobacco products. Not only can dental professionals provide cessation support or referral for counseling, but they can also help prevent nicotine addiction in the first place.

REFERENCES

- American Lung Association. Trends in Tobacco Use. Available at: www.lungusa.org/finding-cures/our-research/trend-reports/Tobacco-Trend-Report.pdf. Accessed September 1, 2011.

- Secondary Smoking, Individual Rights, and Public Space. The Reports of the Surgeon General. Available at: http://profiles.nlm.nih.gov. Accessed September 1, 2011.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2011 Smoking and Tobacco Use. Available at: www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/economics/econ_facts/index.htm. Accessed September 1, 2011.

- US Food and Drug Administration. “Light” Tobacco Products Pose Heavy Health Risks. Available at: www.fda.gov/ForConsumers/ConsumerUpdates/ucm227360.htm. Accessed September 1, 2011.

- National Cancer Institute. Risks Associated With Smoking Cigarettes With Low Machine-Measured Yields of Tar and Nicotine. Available at: http://cancercontrol.cancer.gov. Accessed September 1, 2011.

- Henningfield J, Fant R, Radzius, A, Frost S. Nicotine concentration, smoke ph and whole tobacco aqueous ph of some cigar brands and types popular in the United States. Nicotine Tob Res. 1999;1:163-168.

- National Cancer Institute. Cigars: Health Effects and Trends. Smoking and Tobacco Control. Available at: http://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/. Accessed September 1, 2011.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Tobacco use among middle and high school students-United States, 2002. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52:1096-1098.

- Wilson D. Flavored tobacco pellets are denounced as a lure to young users. New York Times. April 19, 2010.

- Connolly G, Richter P, Aleguas A, Pechacek T, Stanfill S, Alpert H. Unintentional child poisonings through ingestion of conventional and novel tobacco products. Pediatrics. 2010;125:896-899.

- Nelson R. Snus Raises Risk for Pancreatic Cancer but Is Less Toxic Than Smoking. Available at: www.medscape.com/viewarticle/556437. Accessed September 1, 2011.

- Luo J, Ye W, Zendehdel K, et al. Oral use of Swedish moist snuff (snus) and risk for cancer of the mouth, lung, and pancreas in male construction workers: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2007;369: 2015-2020.

- Savage L. Experts fear Swedish snus sales in the US could thwart antitobacco measures. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:1358-1365.

- American Cancer Society. What about more exotic forms of smoking tobacco, such as clove cigarettes, bidis, and hookahs? Available at: www.cancer.org/Cancer/CancerCauses/TobaccoCancer/QuestionsaboutSmokingTobaccoandHealth/questions-about-smoking-tobacco-and-healthother-forms-of-smoking. Accessed September 1, 2011.

- Knishkowy B, Amiti Y. Water-pipe (narghile) smoking: an emerging health risk behavior. Pediatrics. 2005;116:113-119 .

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hookahs, Smoking and Tobacco Use. Available at: www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/tobacco_industry/hookahs. Accessed September 1, 2011.

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA and Public Health Experts Warn About Electronic Cigarettes. Available at: www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/ Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm173222.htm. Accessed September 1, 2011.

- 2008 PHS Guideline Update Panel, Liaisons, and Staff. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update U.S. Public Health Service Clinical Practice Guideline executive summary. Respir Care. 2008;53: 1217-1222.

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA 101: Smoking Cessation Products. Available at: www.fda.gov/ForConsumers/ConsumerUpdates/ucm198176.htm. Accessed September 1, 2011.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. September 2011; 9(9): 30, 33-34, 36-37.