MANIPULATED ARTWORK TO SIMULATE TREACHER COLLINS PHYSIOLOGY: BANKSPHOTOS/E+/GETTY IMAGES PLUS: PHOTO-MANIPULATION BY JON FRAZE

MANIPULATED ARTWORK TO SIMULATE TREACHER COLLINS PHYSIOLOGY: BANKSPHOTOS/E+/GETTY IMAGES PLUS: PHOTO-MANIPULATION BY JON FRAZE

Treating Patients with Treacher Collins Syndrome

This patient population experiences a spectrum of craniofacial abnormalities that severely impact oral health.

This course was published in the March 2022 issue and expires March 2025. The author has no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Identify the etiology of Treacher Collins syndrome.

- List manifestations of the disorder that pose oral health challenges.

- Describe oral care protocols for patients with dysphagia, low salivary flow, and cleft lip and/or palate.

Treacher Collins syndrome is a genetic disorder affecting the development of the craniofacial complex; it arises between the fifth week and eighth week of embryonic development. The disorder is caused by a failure of the neural crest cells—which are integral to the typical evolution of the tissues of the face, neck, and oral cavity—to develop and function properly.1–4

The hallmark of Treacher Collins syndrome is hypoplasia, or underdevelopment of many of the facial structures such as the zygomatic arches, mandible, and maxilla. This underdevelopment contributes to the onset of malocclusions, mouth breathing, and crowding of teeth, all of which pose oral health challenges.

The genetic disorder can be inherited in an autosomal dominant or autosomal recessive manner, with most cases being autosomal dominant. The syndrome is caused by mutations in several genes including TCOF1, POLR1B, POLR1C, and POLR1D, with mutation to the TCOF1 gene accounting for 81% to 93% of all cases.5 Mutations to TCOF1 and POLR1D genes result in an autosomal dominant pattern, whereas an autosomal recessive pattern is associated with mutation the POLR1C gene.5 Approximately 40% of autosomal dominant cases are inherited from an affected parent, with 60% of cases representing new mutations.5-8 While the disorder shows no predilection for sex or race, it is rare—affecting one out of 50,000 live births.7,8

Clinical Manifestations

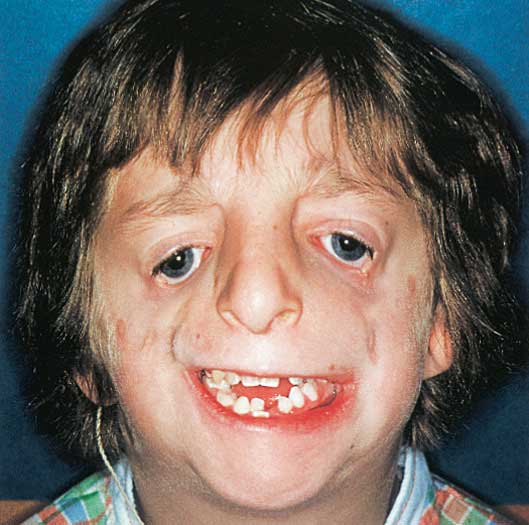

The most common manifestations—shared by 80% to 99% of individuals with Treacher Collins syndrome—are downward slanted palpebral fissures, hypoplastic zygomas, flattened malar processes, and a hypoplastic maxilla.9–11 The downward slanting of the palpebral fissures renders a saddened facial appearance.2 Problems with tissue surrounding the eye occur in 69% of the cases and include a cleft on the lower eyelid called a coloboma and an absence of lashes medial to the coloboma (Figure 1).6,8

A majority of individuals with Treacher Collins syndrome have underdeveloped zygomatic arches and malar processes, giving the face a flattened or sunken appearance.2,9 Cheek reconstruction is often necessary to repair the defects. The jaws can demonstrate significant underdevelopment, resulting in skeletal and dental malocclusions. A hypoplastic or underdeveloped maxilla can lead to malocclusions, crowded and malposed teeth, and open bites often creating temporomandibular joint (TMJ) problems.6,8,10,12 Mouth breathing is also common in patients with Treacher Collins syndrome and is associated with malocclusions, particularly those with a high palate, narrow maxilla, or anterior open bite. A cleft palate develops in approximately 30% of this patient population.13

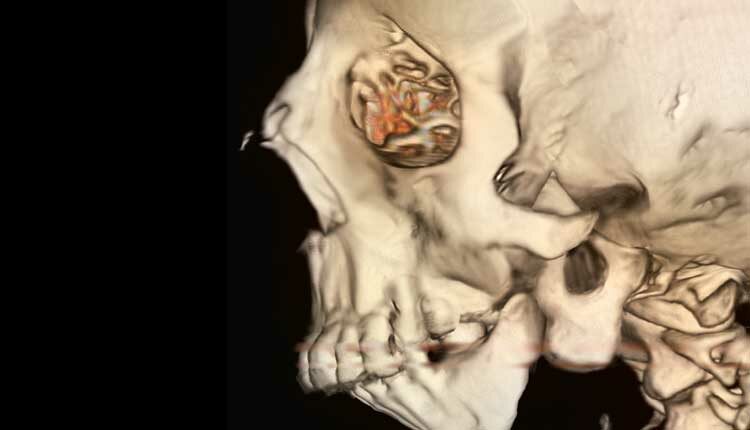

Hypoplastic condyles and coronoid processes are other common features of Treacher Collins syndrome. Condylar hypoplasia manifests as flattened or absent condyles, which can lead to TMJ dysfunction, especially limited mouth opening.2,7,8,13

Hypoplastic condyles and coronoid processes are other common features of Treacher Collins syndrome. Condylar hypoplasia manifests as flattened or absent condyles, which can lead to TMJ dysfunction, especially limited mouth opening.2,7,8,13

Around the mouth, a downward sloping of the commissures can give the individual a frowning expression. Mandibular hypoplasia is another common manifestation—occurring in 78% of cases—that results in a micrognathic jaw and receding chin.6,9 A micrognathic jaw can contribute to swallowing and breathing difficulties.2 Glossoptosis or a tongue that is displaced back in the throat can result from a micrognathic mandible and impacts swallowing and breathing.2,8 Hypoplasia of the pharyngeal structures can also lead to difficulties with feeding and breathing. The most severe cases will result in a restricted airway and life-threatening respiratory problems.9 Obstructive sleep apnea has also been documented in cases of Treacher Collins syndrome.2

External ear anomalies include malformed pinnae or accessory parts.8 Hearing loss occurs in approximately 50% of individuals with the disorder, resulting from ankylosis, or the underdevelopment or absence of the ossicles of the middle ear, which are responsible for transmitting sound.5,8,9 Stenosis of the external auditory meatus is another manifestation that can contribute to hearing loss.2 This hearing loss exacerbates the communication difficulties faced by this patient population.7

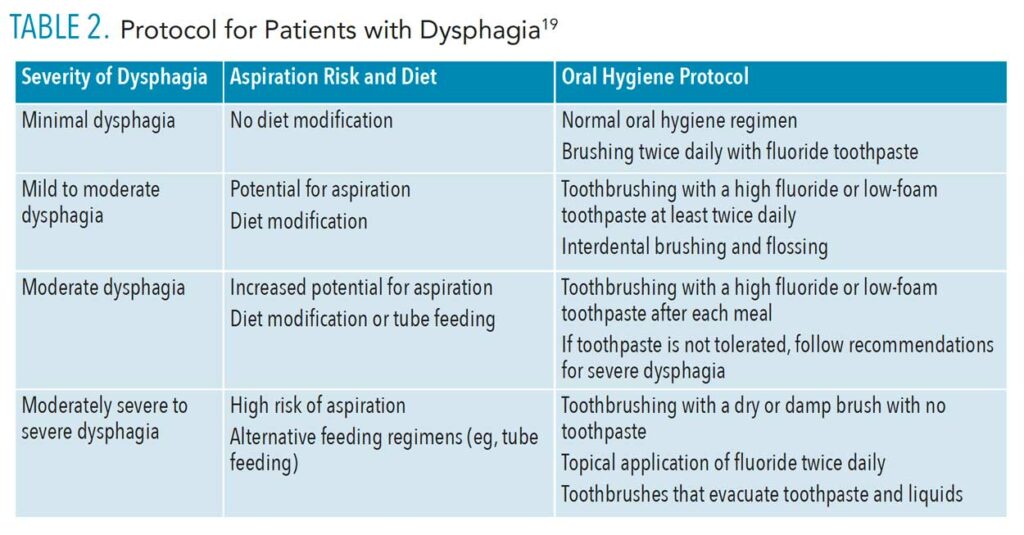

![TABLE 2. Protocol for Patients with Dysphagia]() Treatment

Treatment

With no known cure for Treacher Collins syndrome, treatment is based on the severity of symptoms and the individual needs of the patient.9 Effective treatment requires a team approach involving craniofacial surgeons, nurses, speech-language pathologists (SLPs), oral surgeons, orthodontists, dentists, and dental hygienists.2,8

Patients with Treacher Collins syndrome may require multiple surgeries to correct defects.2,9 Surgical reconstruction for cleft palate, severe malocclusions, and ear malformations may be necessary. Hearing abnormalities are treated by audiologists and otolaryngologists in conjunction with SLPs.14 SLPs are instrumental to the diagnosis and treatment of patients with dysphagia or those needing to be tube fed.

An optimal approach is for parents to seek treatment from an already assembled team of specialists housed under one complex in a craniofacial facility. Referrals to such centers can be obtained from attending physicians, nurses, and pediatricians around the birth of an infant.

For the oral health professional, care will entail expanding the treatment plan to address the challenges faced by patients with Treacher Collins syndrome, such as increased risk for caries, periodontal diseases, and aspiration pneumonia associated with dysphagia and tube feeding. Other challenges include reduced salivary flow, cleft lips and palates, and severe malocclusions.

Reduced Salivary Flow

Malocclusions and crowded dentitions can significantly impact the oral health of patients with Treacher Collins syndrome. Duque and Cardoso8 reported a high plaque index and reduced salivary flow in the cohort of patients with the genetic disorder. Østerhus et al15 reported almost all participants in their study demonstrated low salivary flow; they concluded that mild to severe salivary gland dysfunction may be associated with Treacher Collins syndrome.

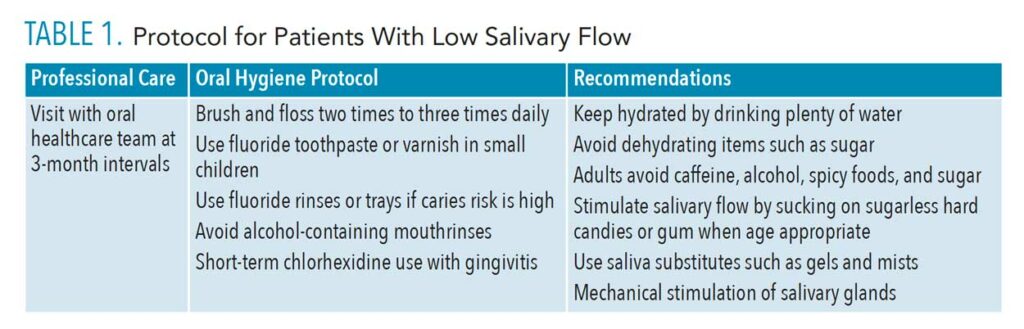

This patient population is at high risk for mouth breathing, which dries out the oral mucosa.16 Reduced salivary flow and mucosal dryness increase the risk of caries and periodontal diseases.8,14 Dryness can also change the balance of the oral flora, increasing the risk for candidiasis. Other undesirable effects include changes in taste perception, glossitis, and glossodynia. The dental team can implement protocols to assist patients with reduced salivary flow such as toothbrushing more than twice per day to improve moisture via mechanical stimulation of salivary glands (Table 1).17

Dysphagia

Dysphagia, or difficulty swallowing, has multiple causes, but in patients with Treacher Collins syndrome, the hypoplastic development of the anatomy of the jaws and surrounding tissues impacts the swallowing mechanism.18 In patients with cleft lip and/or palate, problems with dysphagia can be compounded.

Dysphagia is addressed by a coordinated effort between a SLP, dietitian, dentist, and caregiver. Using video fluoroscopy and endoscopy, the SLP assesses the function and severity of the dysphagia. He or she determines the feeding method and makes recommendations on changes to the diet texture and/or fluid consistency for ease of swallowing.19 Dysphagia poses oral health risks because liquids are often thickened with cariogenic carbohydrates, increasing caries risk. The dietitian can make recommendations to reduce consumption of cariogenic foods.19

Maintaining oral health is imperative for patients with dysphagia due to the increased risk of aspiration pneumonia, particularly in patients with high bacteria counts in dental plaque.18–20 Oral health professionals need to implement precautions to minimize aspiration by modifying patient positioning. Patients should never be in a supine position nor with the dental chair tilted more than 45°. The patient’s head should be positioned in a slight head tilt with a chin tuck, and adequate suction and saliva evacuation should always be used.18 The patient should be given frequent breaks and the use of any equipment that generates copious amount of water, such as high-speed drills and ultrasonic scalers, should be avoided or limited.20 The use of a rubber dam during restorative procedures can also minimize the risk for aspiration.

During treatment, the oral health professional should be aware of the signs of dysphagia because not all patients have a protective reflex such as coughing or choking.18 These include excessive drooling or saliva and water in the oral cavity, gurgly voice, leaking from the nasal cavity, and difficulty breathing and swallowing.18 The dental team needs to implement oral hygiene protocols to address the various needs of the patient based on the severity of dysphagia and risk for caries and periodontal diseases, as optimal oral hygiene significantly reduces the risk for aspiration pneumonia (Table 2).18,19

Tube Feeding

Tube feeding is often recommended as a means of nutrition for patients with severe dysphagia. Patients who are tube fed are at great risk for aspiration pneumonia and often experience a high level of calculus buildup and dental erosion secondary to gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).20,21 The oral health professional should carefully examine teeth for signs of erosion as heavy calculus deposits could conceal the effects. GERD also poses a risk for aspiration of stomach contents.

Patients who are tube fed do not produce normal amounts of saliva due to a lack of stimulation from mastication. Without adequate lubrication, mastication is compromised, and the patient is unable to form a passable bolus.21 To avoid this, the dentition and oral cavity should be debrided regularly. A protocol for low salivary output can be implemented. For patients who cannot expectorate, a fluoride mouthrinse can be used instead of a foaming toothpaste in conjunction with a toothbrush that evacuates liquids.

Patients who are tube fed often develop discomfort with foreign objects in the oral cavity, so modifications to the oral hygiene regimen should be made, such as using smaller toothbrushes (finger brushes), swabs, or wipes.21 In addition, intraoral and extraoral manipulation of tissues should be performed at recare appointments and at home to desensitize the area.20

Cleft Lip and/or Palate

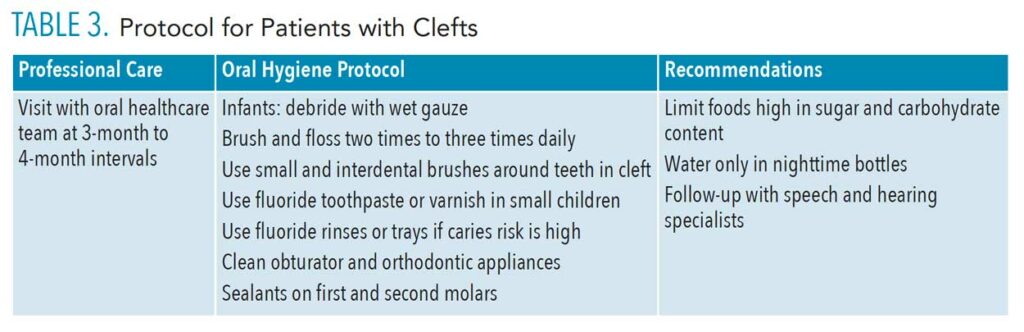

Patients with a cleft lip and/or palate require ongoing preventive dental treatment in conjunction with a team of specialists (Table 3). Patients will require surgeries to correct cleft defects but also orthodontics and orthopedic surgery to address severe malocclusions. The goal is for optimal oral health throughout this extended period of development.

Early in infancy, the most critical issue is the inability to properly suckle and feed due to the clefts in the lip and/or palate. Feeding difficulties must be addressed early to avoid malnutrition.22 Specialized bottles and nipples are recommended until a feeding obturator can be fabricated that will close the oral nasal fistula and improve the intraoral pressure to allow suckling.23 Lip repair is performed between 3 months and 6 months and the palate between 6 months and 18 months.24 Oral hygiene education and nutritional counseling for parents can be initiated early to help them understand the risks of oral disease well before eruption of the teeth. Parents should be educated on how to debride the oral cavity with wet gauze after feedings and how to clean the obturator. Nutritional counseling should emphasize the use of low cariogenic beverages in baby bottles.

Patients should be evaluated by a dental care team as soon as teeth erupt to help reinforce good oral hygiene regimens. Educating the caregiver on the etiology of tooth decay and how it can be prevented is imperative.22 Caries risk in patients with cleft lip and/or palate is high due to the crowded and malposed teeth, supernumerary or missing teeth, and malocclusions. Children with clefts develop 3.5 times more carious surfaces than children without clefts, particularly in the primary dentition.25 The involved teeth are most often located around the cleft, hindering the access necessary for effective oral hygiene. Demonstrations on how to debride teeth—especially around the cleft—and how to clean the obturator are essential since children who wear an intraoral appliance are 7.6 times more likely to develop caries before they turn 3 than those who do not.25

Early in the mixed dentition period, removable appliances—such as palatal expanders— are often used to correct malposed teeth, crossbites, and malocclusions.26,27 Similar to the obturator, removable appliances increase the risk for tooth decay, as the surfaces of the fixtures can accumulate plaque. Oral hygiene care of the dentition and appliances should be reemphasized at recare appointments. Pit and fissure sealants and fluoride varnish are also effective prevention methods. Definitive orthodontic treatment and orthognathic surgery to correct jaw relationships are usually planned for after all permanent teeth have erupted.26 Orthodontic care can last several years, making meticulous oral hygiene and continued nutritional counseling key to preventing decalcification and caries.

Conclusion

Patients with Treacher Collins syndrome display a wide array of craniofacial abnormalities that severely impact oral health. The anatomy of these abnormalities increases the risk for caries, periodontal diseases, and aspiration pneumonia. Patients experience decreased salivary flow, difficulty swallowing, and speech problems. Specific protocols are required for healthcare providers to effectively address the oral health challenges these patients face, and oral health professionals are of the utmost importance in helping these patients maintain their oral health.

References

- Mehrotra D, Hasan M, Pandey R, Kumar S. Clinical spectrum of Treacher Collins syndrome. J Oral Biol Craniofac Res. 2011;1:36-40.

- National Organization for Rare Disorders. Treacher Collins Syndrome. Available at: rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/treacher-collins-syndrome/. Accessed February 25, 2022.

- Cordero DR, Brugmann S, Chu Y, Bajpai R, Jame M, Helms JA. Cranial neural crest cells on the move: their roles in craniofacial development. Am J Med Genet A. 2011;155A:270–279.

- Fehrenbach M, Popowics T. Illustrated Dental Embryology, Histology and Anatomy. 4th ed. St. Louis: Saunders Elsevier; 2015:26.

- Medline Plus. Treacher Collins Syndrome. Available at: medlineplus.gov/genetics/condition/treacher-collins-syndrome/#references. Accessed February 25, 2022.

- Shete P, Tupkari J, Benjamin T, Singh A. Treacher Collins syndrome. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2011;15:348–351.

- da Silva Dalben G, Teixeira das Neves L, Ribeiro Gomide M. Oral health status of children with Treacher Collins syndrome. Spec Care Dentist. 2006;26:71–87.

- Duque C, Cardoso I. Treacher Collins syndrome and implications in the oral cavity. Clin Res Trials. 5: 2019;5:1–5.

- Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center. Treacher Collins Syndrome. Available at: rarediseases.info.nih.gov/diseases/텔/treacher-collins-syndrome. Accessed February 25, 2022.

- Renju R, Varma BR, Kumar SJ, Kumaran P. Mandibulofacial dysostosis (Treacher Collins syndrome): a case report and review of literature. Contemp Clin Dent. 2014;5:532–534.

- Kasat V, Baldawa R. Treacher Collins syndrome—a case report and review of literature. J Clin Exp Dent. 2011;3:E395–E99.

- Cabanillas-Aquino AG, Rojas-Yauri MC, Atoche-Socola KJ, Arriola-Guillén LE. Assessment of craniofacial and dental characteristics in individuals with treacher collins syndrome. A review. J Stomatol Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2021;122:511–515.

- Ibsen OA, Phelan JA. Oral Pathology for the Dental Hygienist. 7th ed. St. Louis: Saunders Elsevier; 2014:200–201.

- Hylton JB, Leon-Salazar V, Anderson GC, De Felippe NL. Multidisciplinary treatment approach in Treacher Collins syndrome. J Dent Child (Chic). 2012;79:15–21.

- Østerhus IN, Skogedal N, Akre H, Johnsen UL, Nordgarden H, Åsten P. Salivary gland pathology as a new finding in Treacher Collins syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2012;158A:1320–1325.

- Tamkin J. Impact of airway dysfunction on dental health. Bioinformation. 2020;16:26–29.

- Furuta M, Yamashita Y. Oral health and swallowing problems. Curr Phys Med Rehabil Rep. 2013;1:216–222.

- Quek HC, Lee YS. Dentistry considerations for the dysphagic patient: recognition of condition and management. Proceedings of Singapore Healthcare. 2019;28(4):288–292.

- Lim M. Basic oral care for patients with dysphagia—a special needs dentistry perspective. Am J Speech-Lang Pathol. 2018;20:142–149.

- Dyment HA, Casas MJ. Dental care for children fed by tube: a critical review. Spec Care Dentist. 1999;19:220–224.

- CHC Solutions Inc. Dental Care for Children Who Are Tube Fed. Available at: chcsolutions.com/continuum_connect/enteral-nutritional/dental-care-for-kids-who-are-tube-fed/. Accessed February 25, 2022.

- Rivkin CJ, Keith O, Crawford PJ, Hathorn IS. Dental care for the patient with a cleft lip and palate. Part 1: From birth to the mixed dentition stage. Br Dent J. 2000;188:78–83.

- Tirupathi SP, Ragulakollu R, Reddy V. Single-visit feeding obturator fabrication in infants with cleft lip and palate: a case series and narrative review of literature. Int J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2020;13:186–191.

- FDI World Dental Federation. Oral Health in Comprehensive Cleft Care. Available at: fdiworlddental.org/oral-health-comprehensive-cleft-care-0. Accessed February 25, 2022.

- Pierin, JA, Bowen DM. Darby and Walsh’s Dental Hygiene Theory and Practice. 5th ed. Maryland Heights, Missouri: Elsevier; 2020:965.

- Rivkin CJ, Keith O, Crawford PJ, Hathorn IS. Dental care for the patient with a cleft lip and palate. Part 2: The mixed dentition stage through to adolescence and young adulthood. Br Dent J. 2000;188:131–134.

- American Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Association. Dental Care for Child with Cleft Lip and Palate. Available at: acpa-cpf.org/wp-content/uploads/떒/葑/Dental-Care-2017.pdf. Accessed February 25, 2022.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. March 2022;20(3):34-37.