Tooth Wear and Dentin Hypersensitivity

Etiology, management, and prevention.

Tooth wear continues to affect a large portion of the population and often leads to painful dentin hypersensitivity. Understanding the possible causes of tooth wear may assist dental professionals in managing and preventing the resulting sensitivity.

Tooth wear originates from different chemical and physical factors,1 and is defined as a noncarious loss of hard tissue by erosion, attrition, abrasion, abfraction, bruxism, or genetic considerations.2 Tooth wear may also be caused by the use of whitening agents or medications. This multifaceted phenomenon makes pinpointing one specific cause difficult. A certain amount of tooth wear over time is expected but some individuals exhibit pathologic tissue deterioration that may require intervention.

ETIOLOGY AND TOOTH WEAR CLASSIFICATION

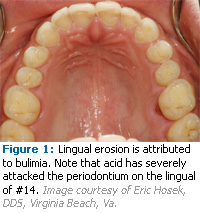

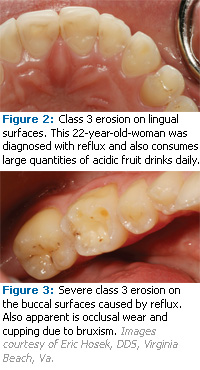

Tooth wear can be classified into six causative categories: erosion, attrition, abrasion, abfraction, bruxism, and genetic considerations. Erosion is the loss of tooth structure by a chemical agent unrelated to a bacterial process.3 There are three types of erosion: extrinsic, intrinsic, and idiopathic. Extrinsic erosion is caused by exogenous acids. It is related to diet, lifestyle, or environment and affects facial and occlusal surfaces (see Figure 1). Intrinsic erosion is caused by endogenous acid such as gastric acid. Acid contacts the lingual surfaces of the teeth during recurrent vomiting, regurgitation, or acid reflux (see Figures 2 and 3). Self-induced eating disorders of psychosomatic origin, such as nervous vomiting, anorexia nervosa, or bulimia, are often the cause of regurgitation or vomiting. Causes of somatic origin include pregnancy, alcoholism, and gastrointestinal disorders such as gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). The most frequently consumed erosive acids are fruit acids and phosphoric acid contained in fresh fruits, fruit juices, and soft drinks. Idiopathic erosion is caused by acids of unknown origin where there is no etiologic explanation.

With the global rise in soft drink and sports drink consumption, the rate of tooth erosion is also increasing. Soft drink and juice consumption has more than doubled over the past 30 years. Among adolescents, the average soda intake is 24 ounces per day or more than 700 cans per person per year.4 The increased demand for tooth whitening has also contributed to burgeoning rates of extrinsic erosion and hypersensitivity. Medications, such as powdered aspirins and asthmatic drugs that have low pH values, may also have an impact on erosion.

Attrition is the physiologic wearing away of tooth structure due to tooth-to-tooth contact occurring on the occlusal and incisal surfaces, which happens during mastication. Abrasion is the pathologic wearing away of tooth structure through abnormal mechanical movements; for example, by excessive tooth brushing using an incorrect technique with abrasive toothpaste. Abfraction refers to wedge-shaped defects primarily found on facial surfaces attributed to parafunctional habits. Bruxism is grinding or clenching during nonfunctional mandibular movements. Genetic considerations affect the quality and/or quantity of enamel, thus increasing vulnerability to tooth wear. An example of a genetic consideration is amelogenesis imperfecta, a disorder of dentition development that causes teeth to be more prone to tooth wear and breakage and to appear pitted or grooved, very small, and discolored.

Attrition is the physiologic wearing away of tooth structure due to tooth-to-tooth contact occurring on the occlusal and incisal surfaces, which happens during mastication. Abrasion is the pathologic wearing away of tooth structure through abnormal mechanical movements; for example, by excessive tooth brushing using an incorrect technique with abrasive toothpaste. Abfraction refers to wedge-shaped defects primarily found on facial surfaces attributed to parafunctional habits. Bruxism is grinding or clenching during nonfunctional mandibular movements. Genetic considerations affect the quality and/or quantity of enamel, thus increasing vulnerability to tooth wear. An example of a genetic consideration is amelogenesis imperfecta, a disorder of dentition development that causes teeth to be more prone to tooth wear and breakage and to appear pitted or grooved, very small, and discolored.

DENTIN HYPERSENSITIVITY

Dentin hypersensitivity is characterized by sharp, transient pain in response to mechanical, chemical, or thermal stimuli when no other dental pathology is apparent.5 Hypersensitivity is not well understood and the degree of pain is highly variable among individuals. The hydrodynamic theory, which is generally accepted as the cause of dentinal hypersensitivity, proposes that fluid movement within dentinal tubules stimulates nerve receptors of the pulp tissue, causing the sensation of pain.6 Patients can help dental professionals diagnose dentin hypersensitivity by identifying triggers such as temperature, pain duration, acid in diet, etc.

TABLE 1. RISK FACTORS FOR HYPERSENSITIVITY IN YOUNGER ADULTS

- Excessive soft drink consumption/duration of exposure

- Excessive sports drink consumption/duration of exposure

- Fruit juice consumption

- Iced tea consumption

- Eating disorders

- Use of chewable vitamins

- Methamphetamine use

- Xerostomia from drug use

- Congenital factors

RISK FACTORS/MANAGEMENT

The traditional approach to dentin hypersensitivity has focused on isolated treatment with little regard for predisposing factors. A broader-based approach that includes the consideration of causative factors and expanded management strategies may be more effective.

Age may affect the development of hypersensitivity. Although not mutually exclusive to any age group, certain risk factors seem to affect particular age groups. Tables 1 and 2 include risk factors for younger and older adults.

In order to reduce the noncarious destruction of tooth structure, dental professionals need to diagnose the type of tooth wear, grade the severity of the wear (see Tables 3 and 4), determine the causative factors, implement appropriate treatment to remove or alter causative factors, and monitor progress.

Patients’ medical histories should include a list of all prescription and over-the-counter medications used. Frequent antacid use may indicate an undiagnosed case of GERD. Radiation therapy may affect salivary glands. The dental history should include the dentrifices used, toothbrush hardness, toothpaste abrasiveness, misuse of toothpicks, oral habits, etc. Hobbies such as wine tasting may also contribute to erosion.

The clinical examination should include a thorough head and neck exam to evaluate masticatory muscle function. An enlarged parotid gland may indicate bulimia, alcoholism, or Sjogren’s syndrome. Alcoholism may also present as enlarged superficial facial capillaries. Pathologies such as caries, recent restorations, cracked tooth syndrome, fractured restoration, gingivitis, pulpitis, and marginal leakage should be ruled out.

A dietary analysis should be included because the acidity, frequency, and exposure time of food intake are relative. Reasonable and achievable changes to the diet should be recommended as the suggestion of radical changes will most likely be unsuccessful. Advice should be provided on how to modify acid intake and frequency.

Patients should be advised about modifying or removing causative factors like nail biting, pen chewing, pipe use, and the misuse of toothpicks. Oral hygiene habits, such as using low abrasive toothpastes and incorporating fluoride, should be discussed.

PROFESSIONAL PREVENTION

Although tooth wear is an increasing problem, forecasting who will be affected is difficult, therefore, complete prevention may be unachievable. Preventing further tooth wear is possible and dental professionals need to be aware of subtle changes in wear patterns. When recommending prevention strategies, cause and history of enamel wear should be considered. Many professional strategies are now available to treat the symptoms of hypersensitivity from fluoride varnish to calcium phosphate technologies.

The use of glass ionomer restorations may be helpful. Some studies have demonstrated that resin-based sealants and bonding agents reduce erosion progression.10 Calcium phosphate technologies release calcium and phosphate ions that plug tubules and block nerve endings from the pain stimulus. These technologies include amorphous calcium phosphate, calcium sodium phosphosilicate, and casein phosphopeptide-amorphous calcium phosphate. They are available in some over-the-counter products as well as professionally applied products.11

A new arginine/calcium/bicarbonate compound is available that binds to the dentin and occludes the open dentinal tubules with the arginine acting as a carrier for calcium and phosphorous.11

Oxalates may be used because they react with calcium to form calcium oxalate, which occludes dentin tubules. Chemical desensitizers penetrate tubules precipitating plasma proteins to close tubule lumen. Dentin bonders and surface sealers/self-etch primers can penetrate and seal tubules.11<-/span>

An annual update of the patient’s complete periodontal charting should be done and a review of models and intra-oral photographs can assist in monitoring wear patterns, as well as identify possible future areas of wear.

For those patients who are undergoing tooth whitening, adding potassium nitrate or fluoride dentifrice to the whitening trays and reducing the concentration of the whitening agent may reduce this type of sensitivity.

TABLE 2. RISK FACTORS FOR HYPERSENSITIVITY IN OLDER ADULTS

- Xerostomia, which prevents natural acid buffering from saliva, due to medication use

- Hiatus hernia

- Reflux/GERD

- Increased stomach acid

- Alcohol abuse

- Wine consumption

- Congenital factors

- High acidic or vinegary food consumption

PROACTIVE PATIENT STRATEGIES

Patients should also be advised on changes they can make to reduce their incidence of dentin hypersensitivity. Diet is important because an acidic diet coupled with brushing may play a part in tooth wear and dentin hypersensitivity.7 Reducing or eliminating acidic foods, drinks, and carbonated beverages may also be helpful as well as consuming a neutral food such as milk following a meal or after the consumption of an acidic food. Very hot or very cold foods should be avoided.

Patients should also be advised on changes they can make to reduce their incidence of dentin hypersensitivity. Diet is important because an acidic diet coupled with brushing may play a part in tooth wear and dentin hypersensitivity.7 Reducing or eliminating acidic foods, drinks, and carbonated beverages may also be helpful as well as consuming a neutral food such as milk following a meal or after the consumption of an acidic food. Very hot or very cold foods should be avoided.

Patients should be advised to avoid brushing immediately after they have consumed acidic foods because brushing in the presence of acid may contribute to a quicker progression of cervical defects.8 Recent research indicates that normal brushing with or without toothpaste contributes little to enamel wear, however, aggressive brushing with or without toothpaste remains a causative factor.

Patients prone to aggressive brushing should be advised to brush with their nondominant hand to allow for conscious brushing pressure. Manual brushing techniques should be evaluated and long, horizontal strokes should be discouraged. Patients should brush one to two teeth at a time. Patients using power toothbrushes should grip the handle lightly and use light pressure. Patients should be reminded that the object of brushing is to remove soft deposits; hard deposits will be removed by the dental professional.

Acidic mouthrinses should not be used because they may dissolve the smear layer of exposed dentin, increasing the risk of dentin hypersensitivity.

For patients experiencing dentin hypersensitivity, toothpastes with 5% potassium nitrate, which blocks pain sensations by infiltrating the dentinal tubules and depolarizing the nerve, may be helpful. Continued use is recommended to prevent symptoms from returning. Over-the-counter fluoride products and gels along with desensitizing agents can also be recommended. Dentifrice with both potassium nitrate and fluoride can be used to reduce pain and promote remineralization.

Occlusal management is also important. Patients should be advised on stress reduction, which can help relieve excessive clenching and bruxism. A night appliance should be used for unconscious tooth grinding. If dentin hypersensitivity persists after exhausting all management strategies and prevention methods, soft tissue grafting or restorative measures may need to be considered.

There are no hard and fast rules for treating tooth wear-induced hypersensitivity, rather dental professionals must use the tools currently available along with efforts to advise patients about strategies that can be implemented to prevent or reduce dentin hypersensitivity.

REFERENCES

- Bartlett D, Smith BGN. Definition, classification and clinical assessment of attrition, erosion and abrasion of enamel and dentine. In: Addy M, Embery G, Edgar WM, Orchardson R, eds. Tooth Wear and Sensitivity—Clinical Advances In Restorative Dentistry. 1st ed. London: Martin Dunitz; 2000.

- Smith B, Knight J. A comparison of the pattern of tooth wear with aetiological factors. Br Dent J. 1984;157:16-19.

- Sykes L. Dentine hypersensitivity; a review of its aetiology, pathogenesis and management. SADJ. 2007;62:66.

- National Heath and Nutrition Exam Survey 2002. Available at: www.cdc.gov/NCHS/data/nhanes/nhanes_01_02/nhanesoverview_0102.pdf. Accessed May 8, 2009.

- Holland G, Narhi MN, Addy M, Gangarosa L, Orchardson R. Guideline for the design and conduct of clinical trials on dentin hypersensitivity. J Clin Periodontol. 1997;24:808-813.

- Brannstrom M. Sensitivity of dentin. Oral Surg. 1996;21:517-526.

- Addy M. Tooth brushing, tooth wear and dentine hypersensitivity—are they associated? Int Dent J. 2005;(Suppl 1):251-267.

- Smith W, Marchan S, Rafeek RN. The prevalence and severity of non-carious cervical lesions in a group of patients attending a university hospital in Trinidad. J Oral Rehabil. 2008;35:128-134.

- Bartlett D, Smith BG, Wilson RF. Comparison of the effect of fluoride and non-flouride toothpaste on tooth wear in vitro and the influence of enamel fluoride concentration and hardness of enamel. Br Dent J. 1994;176:346-348.

- Azzopardi A, Bartlett DW, Watson TF. The surface effects of erosion and abrasion on dentine with and without a protective layer. Br Dent J. 2004;196:351-354.

- Tilliss T. The source of the pain. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2009;7(4):24-26.

- Carlsson G, Johansson A, Lundqvist S. Occlusal wear. A follow-up study of 18 subjects with extremely worn dentitions. Acta Odontol Scand. 1985;43:83–90.

- Johansson AK, Johansson A, Birkhed D, Omar R, Baghdadi S, Carlsson GE. Dental erosion, soft-drink intake, and oral health in young Saudi men, and the development of a system for assessing erosive anterior tooth wear. Acta Odontol Scand. 1996;54:369–378.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. June 2009; 7(6): 26, 28, 30-31.