Tips for Successfully Serving as Infection Control Coordinator

Myriad resources are available for dental professionals who serve in this important role.

The infection control coordinator or Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) officer is a key member of the dental team. Frequently, oral health professionals are thrust into this role by default. Sometimes this position is filled by dentists, dental hygienists, or dental assistants. Many dentists appoint dental hygienists to serve as infection control coordinators because of their skill and knowledge in the area of infection control. The Commission on Dental Accreditation (CODA) requires dental hygiene programs to graduate students with competence in infection control.1 These competencies (specifically Standard 5-1) include compliance with policies and procedures related to asepsis, hazardous materials, and bloodborne and infectious diseases.1 Oral health professionals are ethically responsible to comply with OSHA and infection control guidelines.2

Ensuring that one dental team member is the point of contact for infection control compliance is critical to the safety of both patients and practitioners. Infection control breaches can be newsworthy, such as the widely publicized case of a Tulsa, Oklahoma, oral surgery office in 2013,3 which affected nearly 7,000 patients over a 6-year period. This infection control breach was linked to five cases of hepatitis B, 74 cases of hepatitis C, and three cases of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).4 Clearly, the stakes in infection control compliance are extremely high.

Many clinicians have questions about where to start when appointed to the role of infection control coordinator. This position is responsible for ensuring that compliance is achieved and maintained, remaining knowledgeable about the subject, serving as the contact point for exposure incidents, and providing training for all staff members or making arrangements for staff to receive appropriate training outside of the office. Individuals who are new to the role of infection control coordinator should start by becoming familiar with OSHA standards and requirements, as well as dental infection control guidelines provided by the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). It is also prudent to collect additional resources for infection control training and instruction.

OCCUPATIONAL SAFETY AND HEALTH ADMINISTRATION

OSHA is an agency within the division of the US Department of Labor that was launched in 1971 to ensure workplace safety.5 As a regulatory agency, OSHA has enforcement capabilities, meaning it can investigate and impose fines. There are two OSHA standards with which dental offices must comply: the OSHA Bloodborne Pathogen (BBP) Standard (29 CFR 1910.1030)6 and the Hazard Communication (HAZCOM) Standard (29 CFR 1910.1200).7

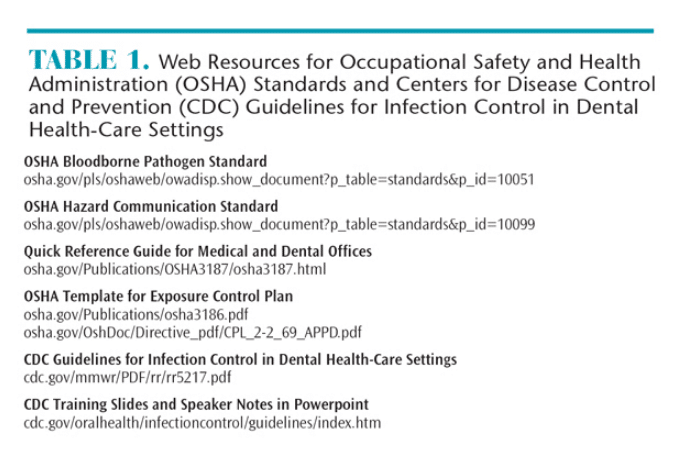

The OSHA BBP standard focuses on preventing the exposure of at-risk employees (those who have the potential for exposure to blood or other potentially infectious material) to bloodborne pathogens such as hepatitis B and HIV. The OSHA BBP standard requires employers to comply with several requirements. First, employers must have an exposure control plan, which is a site-specific document that demonstrates how the office complies with OSHA standards. The plan must include: a copy of the OSHA BBP; list that determines job categories in which employees might have exposure to BBPs; and how the office implements methods of exposure control, such as universal/standard precautions, engineering and work practice controls, personal protective equipment (PPE), housekeeping, employee hepatitis B vaccination records, post-exposure evaluations and follow-up, how hazards are communicated to employees, documentation of training, and record keeping. The exposure control plan must be updated at least annually.8 Table 1 includes a resource that provides templates for creating an OSHA exposure control plan.

The OSHA BBP also states that employers must ensure that employees use universal/standard precautions, as well as engineering controls (safety devices) and work practice controls (safe behaviors). They must provide PPE such as gloves, masks, eye protection, and protective attire (gowns or lab coats) that are laundered either by a service or on-site so employees do not take contaminated garments home. Employers are required to offer the hepatitis B vaccine, and maintain a post-exposure protocol (outlined in the exposure control plan) in case of exposure incidents. Employees have the right to decline the vaccine and post-exposure protocol, but they should be counseled about the risks associated with declination. Employers must provide BBP standard training upon hire, when new job tasks with exposure risks are undertaken, and at least annually. Lastly, the employer is required to maintain personal health records for all at-risk employees and documentation of BBP training.6

Infection control coordinators must also be familiar with the HAZCOM standard, which relates to exposure to chemicals used in the dental office. Employers must implement a HAZCOM program in order to be OSHA compliant. The employer is required to provide a written description of how the office meets the HAZCOM standard that includes: ensuring that hazardous chemicals contain a label; keeping safety data sheets (SDS) for hazardous chemicals in an easily accessed area; and providing training for employees who work with hazardous chemicals.7

In 2013, the HAZCOM standard was revised and became aligned with the Globally Harmonized System of Classification and Labeling of Chemicals, a worldwide universal labeling system for hazardous materials. OSHA required employers to provide staff training on this new system by December 1, 2013. This system requires a uniform labeling system with standard language and signal words, product identifiers, hazard statements, and pictorial diagrams (available for download at osha.gov/dsg/hazcom) for all hazardous materials. Employers are responsible for storing hazardous materials in their original containers with labels that meet the new standard. If a hazardous material must be moved into a new container, the receptacle must include a label with the same information as the original label, including the correct pictorial diagram. Manufacturers of hazardous chemicals are responsible for providing SDSs when products are ordered. Employers must maintain SDSs for each hazardous chemical used in the office and ensure they are accessible to at-risk employees at all times.7 SDSs can be stored as either hard copies or electronic formats. Table 1 includes resources for accessing the two standards, a quick reference guide for medical and dental offices, and HAZCOM pictorial diagrams.

CENTERS FOR DISEASE CONTROL AND PREVENTION GUIDELINES

The 2003 CDC Guidelines for Infection Control in Dental Health-Care Settings9 are the gold standard of infection control protocol in the dental office. Table 1 includes resources for trainers, such as speaker notes and Powerpoint slides. The CDC is currently updating the guidelines and a revised version most likely will be published in 2016. The CDC is an advisory body, not a regulatory agency like OSHA, so it does not have enforcement capability. However, advisory bodies, such as the CDC, are key stakeholders in making evidence-based recommendations for use by regulatory agencies like OSHA and others. OSHA typically works closely with the CDC when guidelines are developed or reviewed.

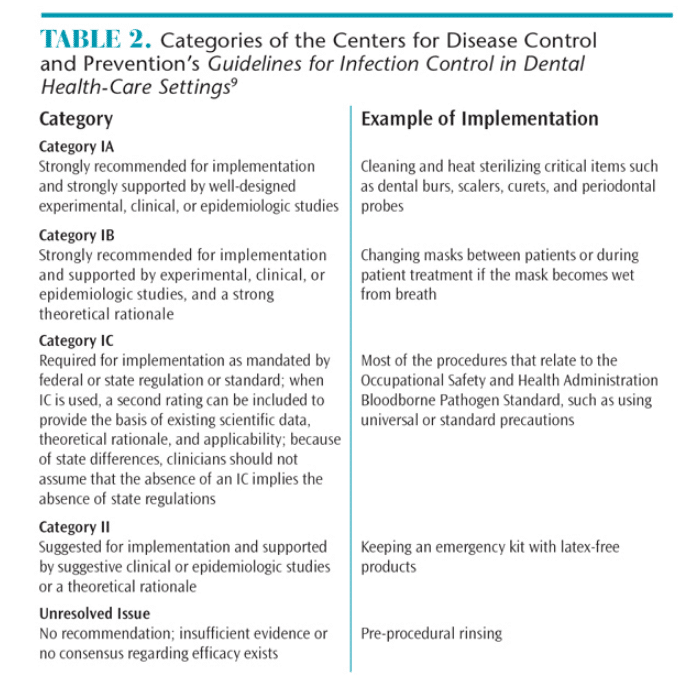

The CDC guidelines should be consulted often and carefully. They provide recommendations that must be interpreted by the practitioner, and they are not always clear-cut. Developing a keen understanding of the guidelines is key to implementing a safe work environment. The CDC guidelines contain evidence-based recommendations for infection control procedures that are categorized according to the supporting data, theoretical rationale, and applicability. Several categories of recommendations have been developed by the CDC and the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC). They are Category IA, IB, IC, II, and Unresolved Issue.9 Table 2 provides a summary of these recommendations.

While items in Category IA and IB are both “recommended for implementation and strongly supported by well-designed experimental, clinical, or epidemiologic studies,”9 items in Category IB are also supported by a strong theoretical rationale. An example of a Category 1A item is the cleaning and heat sterilizing of critical items such as dental burs, scalers, curets, and periodontal probes. Changing a mask between patients or during patient treatment if the mask becomes wet from breath is an example of a Category IB item. Category IC recommendations are required by regulation. Items in this category include most of the procedures outlined in the OSHA BBP standard, such as using universal or standard precautions for all patients. Items in Category II are “suggested for implementation” and supported by suggestive clinical or epidemiological studies or a theoretical rationale. For instance, maintaining an emergency kit with latex-free products is a Category II?item. The final category of Unresolved Issue encompasses those items for which the CDC and HICPAC have no recommendation due to a lack of scientific evidence. Pre-procedural rinsing falls into this category.9

In review, items in Category IA and Category IB are strongly recommended based on research evidence, but not mandatory. Category IC items are required/mandated (enforceable by OSHA). Items in Category II are suggested but not mandatory, while the Unresolved Issue items are not recommended or mandatory.

CHAIN OF INFECTION

In the 1980s, it became clear that bloodborne disease such as hepatitis and HIV could be transmitted via dental procedures—putting workers at risk. A chain of events, however, must be set into motion in order for infection to occur. First, pathogens must be present in sufficient numbers. Then a portal of exit from infectious hosts, as well as a portal of entry into susceptible hosts must be present.9 Implementation of infection prevention measures outlined in the CDC guidelines help to break this chain of infection. The guidelines were developed in the mid-1980s to reduce the risk of disease transmission, and implementation of these guidelines have become second nature over the past two decades. The current CDC guidelines are comprehensive and cover a multitude of topics related to infection control. The use of PPE, increased vaccination rates, and more stringent sterilization procedures have drastically reduced the incidence of diseases, such as hepatitis B, among dental professionals.9

The CDC guidelines provide recommendations related to all elements of the BBP standard. They also include guidance for safe practices related to hand hygiene, PPE, latex hypersensitivity, sterilization and disinfection of instruments, storage of instruments, environmental infection control, dental unit waterlines, handpieces, radiology equipment, single-use disposable items, parenteral medications, pre-procedural rinsing, handling of biopsy specimens, dental laboratory, laser smoke, and prion diseases. Appendices related to disinfectants and sterilants, recommended immunizations for dental health care workers, and methods for sterilizing and disinfecting surfaces and patient care items are also included.9

COMPLIANCE

Compliance with infection control guidelines among US dentists varies.10 A study by Cleveland et al10 measured the compliance of US dental offices (n=3,042) with four key CDC recommendations: presence of an infection control coordinator; maintaining dental unit waterline quality; documenting exposure incidents; and using safe medical devices. The study found that 34% of practices had implemented zero or one of the four recommendations, 40% had implemented two of the recommendations, and only 26% had implemented three or four of the recommendations. The authors suggested that improved knowledge of infection control procedures in the dental setting was needed. Implementing a variety of teaching methods and increasing continuing education requirements, they advised, may help promote a safe clinical environment.10

Developing a comprehensive understanding of the 2003 CDC guidelines is a starting point when determining the infection control compliance level in a dental office. Comparing a dental practice’s infection control protocol to those recommended by the CDC will help dental team members determine their level of compliance. A simple checklist or self-audit is another great tool to assess compliance. Fluent11 describes self-examination as the first and most important step in infection prevention in the dental office.11 The safe practice of dentistry requires thorough knowledge of guidelines and regulations, strong leadership, self-assessment, regular continuing education and training, and continuous monitoring of compliance.11

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

Making sense of the CDC guidelines and OSHA standards can be challenging. Fortunately, there are excellent resources to help. The Organization for Safety, Asepsis, and Prevention (OSAP) was founded in 1984 to promote infection prevention and safety. This organization is composed of educators, clinicians, researchers, and industry stakeholders who have an interest in infection prevention and safety.12 OSAP’s vision is that “every visit is a safe dental visit,” and its mission is “to be the world’s leading provider of education that supports safe dental visits.” OSAP provides publications, checklists, toolkits, educational opportunities, webinars, FAQs, and training materials. Many of the resources are free; however, membership provides additional benefits such as discounts on training materials and continuing education. OSAP created an excellent training guide, CDC Guidelines: From Policy to Practice by OSAP, which uses simple language to guide clinicians in improving their understanding of the CDC guidelines.13

Professional associations such as the American Dental Hygienists’ Association (ADHA) and the American Dental Association (ADA) are additional resources for information related to infection control and prevention.14,15 The ADHA and ADA offer several publications and provide FAQs and links to infection control resources. The ADA catalog contains an OSHA compliance training kit.

The Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology (APIC), whose mission is to “create a safer world through prevention of infection,” is an additional resource for infection control and prevention.16 APIC provides publications, resources, textbooks, continuing education, and regular online newsletters upon subscription.

The world of infection prevention and safety has much to offer. Understanding OSHA regulations and CDC guidelines, as well as utilizing other resources, is the first step when assuming the role of infection control coordinator. Attending continuing education courses geared toward infection prevention and safety is the next step. Coordinators’ continual desire to learn and improve will help their offices remain compliant.

References

- American Dental Association Commission on Dental Accreditation. Standard 5-1. Available at: ada.org/~/media/CODA/Files/2016_dh.ashx. Accessed December 16, 2015.

- Scarlett MI, Grant LE. Ethical oral health care and infection control. J Dent Ed. 2015;79(Suppl):545–547.

- Organization for Safety Asepsis and Prevention. Oklahoma Infection Control Breach. Available at:?osap.org/?page=Oklahoma&hhSearchTerms=%22press+and+release%22. Accessed December 16, 2015.

- Organization for Safety Asepsis and Prevention. Symposium Proceedings. Available at:?c.ymcdn.com/sites/www.osap.org/resource/resmgr/Symposium_2013/OSAP.2013Symp.Proceedings.pdf. Accessed December 16, 2015.

- Occupational Safety & Health Administration. About OSHA at: osha.gov/about.html. Accessed October 10, 2015.

- Occupational Safety & Health Administration. Bloodborne Pathogens Standard. Available at: osha.gov/pls/oshaweb/owadisp.show_document?p_id=10051&p_table=STANDARDS. Accessed December 16, 2015.

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Hazard Communication Standard. Available at: osha.gov/pls/oshaweb/owadisp.show_document?p_table=standards&p_id=10099. Accessed December 16, 2015.

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Model Exposure Control Plan. Available at:?osha.gov/Publications/osha3186.pdf. Accessed December 16, 2015.

- Kohn WG1, Collins AS, Cleveland JL. Guidelines for infection control in dental health-care settings—2003. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2003;52(RR-17):1–61.

- Cleveland JL, Bonito AJ, Corley TJ, Foster M, Barker L, Brown GG. Advancing infectioninfection control in dental care settings: factors associated with dentists’ implementation of guidelines from the centers for disease control and prevention. J Am Dent. 2012;143:1127–1138.

- Fluent MT. Infection control in the dental office: compliance revisited. Inside Dentistry. 2013;9(10):1–4.

- Organization for Safety Asepsis and Prevention. The Safest Dental Visit. Available at: osap.org. Accessed December 16, 2015.

- Organization for Safety Asepsis and Prevention. CDC Guidelines From Policies to Practice. Available at: osap.site-ym.com/store/ViewProduct.aspx?nonssl=1&id=396090 Accessed December 16, 2015.

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association. Health and Safety Resources. Available at: adha.org/resources. Accessed December 16, 2015.

- American Dental Association. Infection Control Resources. Available at:?ada.org/en/member-center/oral-health-topics/infection-control-resources. Accessed December 16, 2015.

- Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology. Spreading Knowledge, Preventing Infection. Available at: apic.org. Accessed December 16, 2015.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. January 2016;14(01):28,30,32,34.