The Therapeutic Use of Botox

Botulinum toxin type A is part of the oral health armamentarium for patients with special needs.

This course was published in the November 2017 issue and expires November 2020. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Define botulinum toxin type A (BoNT-A).

- Discuss BoNT-A’s role in treating dental problems common among patient with special needs.

- Identify its limitations and contraindications.

- Explain the regulatory issues regarding its use in dental care.

While most commonly known for its cosmetic use as a wrinkle reducer, botulinum toxin type A (BoNT-A) is quickly growing in popularity as a therapeutic treatment option for many medical and dental issues related to muscle hyperactivity. In dentistry, a large number of muscle-generated issues require professional attention, such as hypersalivation, bruxism, masseteric hypertrophy, temporomandibular joint disorder (TMD), dysphagia, and oromandibular dystonia (OMD). Muscle-generated problems are often treated with intraoral appliances, occlusal adjustment, dental restorations, medications, and surgery, which can be invasive, expensive, and damaging to tooth structure. Many of these parafunctional habits can be overcome. The injection of BoNT-A is a growing treatment option for many dental issues due to its easy application, efficacy, and minimal side effects.

BoNT-A is a protein produced by the bacterium Clostridium botulinum and may be found naturally in expired or spoiled foods. In high doses, the toxin can result in muscle paralysis. BoNT-A inhibits the release of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, which is responsible for muscle contractions.1 Thus, depending on the concentration, injection of BoNT-A can temporarily reduce or eliminate the intensity of muscle contractions. Over about 3 months, the muscles slowly return to normal contractions and further injections are necessary to maintain the effects.2

BoNT-A is used for a variety of conditions in general medicine—both cosmetic and therapeutic. BoNT-A is approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration for a number of therapeutic uses, such as overactive bladder, chronic migraines, severe neck spasms, hyperhidrosis (excessive sweating), and strabismus.3–7 It has also been prescribed for off-label uses, such as depression, atrial fibrillation, and cleft lip scars.8–10 In dentistry, BoNT-A is used to treat hypersalivation, bruxism and masseteric hypertrophy, TMD, dysphagia, and OMD. These issues commonly appear in those with neuromuscular disorders. BoNT-A has some definite benefits. For one, the dosage for each application can be manipulated depending on the severity of the patient’s condition. The therapeutic uses of BoNT-A in dentistry can be especially beneficial for patients with special needs. A wide variety of conditions, such as Parkinson’s disease, autism, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), brain injury, and cerebral palsy, may cause maxillofacial issues that can be addressed with BoNT-A. For these patients, treatments like oral medications or intraoral appliances are often not ideal due to side effects and difficulty with compliance, especially among children.

HYPERSALIVATION

The inability to properly swallow or hold saliva in the mouth, as well as excessive saliva production, known as sialorrhea, are issues commonly seen in a variety of special needs conditions. This may result in excessive drooling, which can affect quality of life and exert both psychological and physical consequences, such as perioral dermatitis, dehydration, aspiration pneumonia, social embarrassment, and excessive clothing changes.11,12 Traditional first-line treatment for sialorrhea is anticholinergic drugs, which may produce a number of adverse effects, such as blurry vision, drowsiness, and constipation. For more severe cases of sialorrhea or for patients who do not respond well to anticholinergic medication, surgery may be indicated to reposition the submandibular duct or removal of the gland.12

BoNT-A is another less invasive option to treat hypersalivation. Injection of BoNT-A into the submandibular gland and/or parotid gland is used to reduce drooling and salivary buildup in patients with neuromuscular diseases, such as Parkinson’s disease and cerebral palsy.13 Patients with these conditions typically cannot adequately swallow their saliva. If too much BoNT-A is injected or it is injected into the salivary glands of patients with normal or limited saliva flow, dry mouth may result, which can greatly increase caries risk. If BoNT-A is repeatedly applied to the salivary glands as a long-term treatment, atrophy and reduction in salivary gland size may occur, resulting in increased intervals between injections.12 Ultrasound can help locate the salivary gland and guide the injection of BoNT-A, while also measuring gland size to track progress.

One study that evaluated the long-term safety and efficacy of BoNT-A for sialorrhea reported minor rates of complication, ranging from 0% to 11.1% in the submandibular gland.14 Injection of BoNT-A should be considered for patients with sialorrhea or excessive drooling as the evidence suggests it is minimally invasive, effective, well tolerated, and has localized effects. However, the benefits should be weighed against the potential risk of xerostomia.

BRUXISM AND MASSETERIC HYPERTROPHY

Bruxism and clenching are conditions that affect many patients with special needs and may cause substantial wear of the dentition, headaches, damage to the temporomandibular joint (TMJ), masseteric hypertrophy, exacerbation of periodontal disease, and possibly avulsion of permanent teeth.15 In patients with bruxism, occlusal guards, spasmolytic medications, and relaxation therapy are common treatments.16 Many patients with special needs cannot tolerate intraoral appliances and compliance can be difficult. Furthermore, an intraoral appliance may become an aspiration hazard for patients who have difficulty controlling facial muscles.15

Research suggests that injection of BoNT-A into the temporal and masseter muscles to treat severe bruxism may relieve pain and muscle tension in a variety of patients, including those with neurological disorders—such as Rett syndrome, intellectual disability, anoxic encephalopathy, cerebellar hemorrhage, autism, ADHD, and traumatic brain injuries— without significant negative side effects.15–17

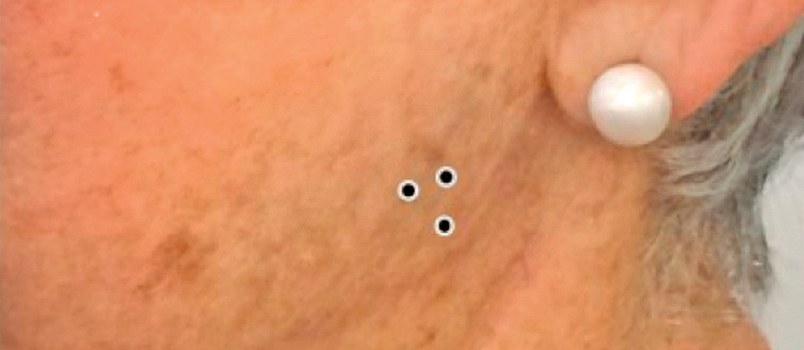

Masseteric hypertrophy may occur in patients who experience chronic jaw clenching or bruxism, resulting in the muscles around the jaw to appear enlarged or deformed. One treatment is surgical resection, which can cause permanent shortening of the muscle or joint. However, if a small amount of BoNT-A is injected (Figure 1), the contraction force of the masseter muscle may be reduced for a time, which can alleviate pain and reduce enlargement of the muscle.1 As with all botulinum toxin treatments, injections must be repeated habitually to maintain desired effects.

TEMPOROMANDIBULAR JOINT DISORDERS

TMD is a broad term describing diseases that impact mastication. These issues frequently originate from either the TMJ or one or more of the masticatory muscles. Symptoms include headaches, neck and/or facial pain, decreased joint movement, joint sounds, and periauricular pain.1 People with TMD may also experience greater damage to teeth, bones, joints, and gingiva.

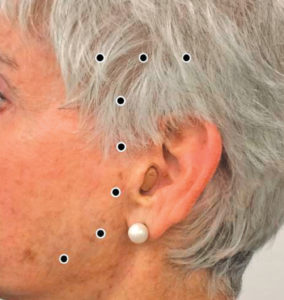

One of the most frequent causes of TMD is bruxism. Treatment options for TMD are occlusal mouthguards, muscle relaxants, oral pharmacotherapy, and biofeedback. Studies suggest that the injection of BoNT-A (Figure 2) may be more successful, longstanding, less invasive, and produce fewer side effects compared with traditional treatments. The duration of efficacy for TMD is approximately 12 weeks, though this is affected by patient circumstances and severity of the condition.18

DYSPHAGIA

Patients with special needs, such as those with cerebral palsy, Parkinson’s disease, and stroke, may also experience difficulty swallowing.19 Patients with muscular mobility issues may not have proper function of their esophageal muscles, resulting in low dysphagia. This is often treated with swallowing therapy, endoscopic esophageal dilation, or oral medications to aid in relaxation of the esophagus, such as calcium channel blockers or proton pump inhibitors.

The use of BoNT-A as a treatment option may increase a patient’s independence in feeding, aid in the swallowing of saliva, and decrease drooling. BoNT-A injection into the cricopharyngeus muscle is effective in patients with underlying muscle spasm or hypertonicity to support swallowing.20 The injection is administered endoscopically when the patient is under general anesthesia and is usually repeated every 3 months to 4 months.20

OROMANDIBULAR DYSTONIA

OMD describes involuntary and repetitive spasms of varying intensities that affect the masticatory, lingual, facial, lip, and pharyngeal muscles.21,22 It may impact patients with Parkinson’s disease, Meige’s syndrome, and traumatic brain injuries.22–24 Symptoms of OMD include bruxism, dysphagia, dysarthria, soft tissue trauma, mandibular deviation, and TMJ subluxation. OMD impacts oral function and the ability to chew, swallow, breathe, and communicate, which, in turn, may lead to shame, reduced quality of life, depression, malnutrition, and weight loss.

Currently, there is no cure for OMD, but patients may manage their conditions using oral medications, dental appliances, or deep brain stimulation surgery.22,25 However, these treatment options have some drawbacks. Oral medications (cholinergics, benzodiazepines, anti-parkinsonism drugs, anti-convulsants) may exert negative side effects, such as seizures, muscle weakness, dizziness, low blood pressure, worsening of limb proprioception and motor fluctuations, confusion, and motor disturbances.22,26 Meanwhile, dental appliances, such as splints or retainers, have limited longevity and may affect speech. Patient compliance is typically low, especially among patients with special needs.25

Intramuscular injections of BoNT-A (Figure 3), directed by electromyographic (EMG) guidance, is an effective treatment option for patients with OMD and is reported to have high success rates of 90% to 95%.22 Using EMG guidance allows for accurate needle placement, lower doses of BoNT-A, and a more localized effect.21,22 BoNT-A is safe, uncomplicated, and highly effective for OMD cases, as well as other conditions involving muscular spasms, but must be repeated every 3 months to 6 months.22

CONTRAINDICATIONS AND LIMITATIONS

BoNT-A’s most significant limitation is that it wears off over time. Depending on the amount injected and the injection site, the effects of BoNT-A may last anywhere from 3 months to 5 months.27 In addition, masticatory function may be inhibited for a short time immediately after the injection is administered.1

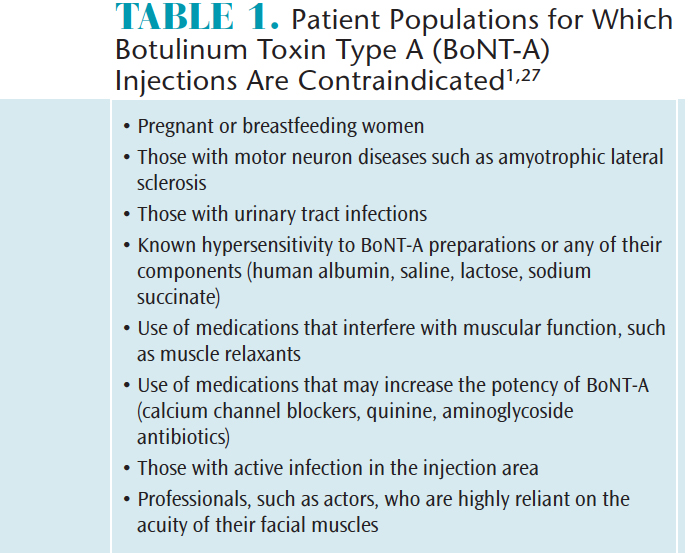

The use of BoNT-A may not be an appropriate treatment for all cases. Table 1 lists populations for who BoNT-A is contraindicated.1,27

REGULATORY REPORT

Each state has its own regulations regarding the use of BoNT-A in dentistry. Most states permit general dentists to inject BoNT-A and dermal fillers after completion of appropriate training.27 Courses can be given either by a dental institution approved by the American Dental Association’s Commission on Dental Accreditation or a continuing education provider.27 The total hours of continuing education required vary by state. For instance, the Massachusetts Board of Registration in Dentistry states that dentists in Massachusetts may inject BoNT-A if they have completed a minimum of 8 hours of training.27 Moreover, these injections can only be performed within the scope of dentistry. Other states, such as California, Michigan, New Hampshire, and North Dakota, also limit the use of BoNT-A to therapeutic treatments. States such as Arkansas, Florida, Louisiana, and Delaware allow both cosmetic and therapeutic uses in dentistry. In Oregon and West Virginia, BoNT-A is restricted to administration by qualified oral and maxillofacial surgeons only.

Could there be potential for the integration of BoNT-A into dental hygiene’s arsenal of treatment options? Currently, only one state allows dental hygienists to administer BoNT-A: Nevada. On November 20, 2015, the Nevada State Board of Dental Examiners passed a motion stating Nevada dental hygienists can perform BoNT-A injections and dermal fillers as long as they hold a valid license to practice and have undergone BoNT-A injection training.28This procedure must be performed under the direct supervision of a dentist licensed to practice in Nevada, who has also undergone training to administer BoNT-A.28 In order to provide a meticulous curriculum, the American Academy of Facial Esthetics started its first live patient training course that included dental hygienists in January 2016.29 This expanded function has the potential to expand career options for dental hygienists, generate higher profits for the practice, and provide patients with additional treatment options.

CONCLUSION

BoNT-A injection has many uses in the dental arena. It is not only effective, but safe, minimally invasive, and exerts few negative side effects. The advantages and disadvantages should be thoroughly considered for each patient. Additionally, regulations and insurance coverage vary state by state.

The integration of BoNT-A into dentistry as a frontline treatment option for dental problems is relevant for all oral health professionals. Dental hygienists play important roles in interprofessional health care and they should remain up to date regarding the use of BoNT-A, so they can effectively educate patients, particularly those with special needs. With this additional training and knowledge, dental professionals are able to create more individualized care plans to improve oral health and alleviate pain.

REFERENCES

- Rao L, PradeepS, Sangur R. Application of botulinum toxin type A: an arsenal in dentistry. Indian JDent Res. 2011;22:440–445.

- Meunier FA,Schiavo G, Molgo J. Botulinum neurotoxins: from paralysis to recovery offunctional neuromuscular transmission. J Physiol Paris.2002;96:105–113.

- Eldred-Evans D,Sahai A. Medium- to long-term outcomes of botulinum toxin A for idiopathic overactivebladder. Ther Adv Urol. 2017;9:3–10.

- Gooriah R,Ahmed F. OnabotulinumtoxinA for chronic migraine: a critical appraisal. Ther ClinRisk Manag. 2015;11:1003–1013.

- Awan KH. Thetherapeutic usage of botulinum toxin (Botox) in non-cosmetic head and neckconditions—an evidence based review. Saudi Pharm J. 2017;25:18–24.

- Lakraj A-AD,Moghimi N, Jabbari B. Hyperhidrosis: anatomy, pathophysiology and treatmentwith emphasis on the role of botulinum toxins. Toxins.2013;5:821–840.

- Saunte JP, HolmesJM. Sustained improvement of reading symptoms following botulinum toxin Ainjection for convergence insufficiency. Strabismus. 2014;22:95–99.

- Wollmer MA, DeBoer C, Kalak N, et al. Facing depression with botulinum toxin: A randomizedcontrolled trial. J Psych Res. 2012;46:574–581.

- Pokushalov E,Kozlov B, Romanov A, et al. Long-term suppression of atrial fibrillation bybotulinum toxin injection into epicardial fat pads in patients undergoingcardiac surgery: one year follow up of a randomized pilot study. CircArrhythm Electrophysiol. 2015;8:1334–1341.

- Chang CS,Wallace CG, Hsiao YC, Chang CJ, Chen PKT. Botulinum toxin to improve results incleft lip repair: a double-blinded, randomized, vehicle-controlled clinicaltrial. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e115690.

- George KS,Kiani H, Witherow H. Effectiveness of botulinum toxin B in the treatment ofdrooling. Br J Oral Maxillofacial Surg. 2013;51:783–785.

- Gok G, Cox N,Bajwa J, Christodoulou D, Moody A, Howlett DC. Ultrasound-guided injection ofbotulinum toxin A into the submandibular gland in children and young adultswith sialorrhoea. Br J Oral Maxillofacial Surg. 2013;51:231–233.

- Suskind DL,Tilton A. Clinical study of botulinum-A toxin in the treatment of sialorrhea inchildren with cerebral palsy. Laryngoscope.2002;112:73–81.

- Chan KH, LiangC, Wilson P, Higgins D, Allen GC. Long-term safety and efficacy data onbotulinum toxin type aan injection for sialorrhea. JAMAOtolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;139:134–138.

- Monroy PG, FonsecaMA. The use of botulinum toxin-a in the treatment of severe bruxism in apatient with autism: a case report. Spec Care Dent. 2006;26:37–39.

- Ivanhoe CB, LaiJM, Francisco GE. Bruxism after brain injury: Successful treatment withbotulinum toxin-A. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 1997;78:1272–1273.

- Tan EK,Jankovic J. Treating severe bruxism with botulinum toxin. J Am DentalAssoc. 2000;131:211–216.

- Mor N, Tang C,Blitzer A. Temporomandibular myofacial pain treated with botulinum toxininjection. Toxins. 2015;7:2791–2800.

- Masiero S,Briani C, Marchese-Ragona R, Giacometti P, Costantini M, Zaninotto G.Successful treatment of long-standing post-stroke dysphagia with botulinumtoxin and rehabilitation. J Rehab Med.2006;38:201–203.

- Ahsan SF,Meleca RJ, Dworkin JP. Botulinum toxin injection of the cricopharyngeus musclefor the treatment of dysphagia. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;122:691–695.

- Sinclair CF,Gurey LE, Blitzer A. Oromandibular dystonia: Long-term management withbotulinum toxin. Laryngoscope. 2013;123:3078–3083.

- Teemul T, PatelR, Kanatas A, Carter L. Management of oromandibular dystonia with botulinum Atoxin: a series of cases. Br J Oral Maxillofacial Surg. 2016;54:1080–1084.

- Bakke M, LarsenBM, Dalager T, Møller E. Oromandibular dystonia—functional and clinicalcharacteristics: a report on 21 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol.2013;115:21–26.

- Pedemonte C,Gutiérrez HP, González E, Vargas I, Lazo D. Use of onabotulinumtoxina inpost-traumatic oromandibular dystonia. J Maxillofacial Surg.2015;73:152–157.

- Watt E, SanganiI, Crawford F, Gillgrass T. The role of a dentist in managing patients withdystonia. Available at:readbyqxmd.com/read/24597030/the-role-of-a-dentist-in-managing-patients-with-dystonia.Accessed October 18, 2017.

- Broccard FD,Mullen T, Chi YM, et al. Closed-loop brain-machine-body interfaces fornoninvasive rehabilitation of movement disorders. Ann BiomedEng. 2014;42:1573–1593.

- Nayyar P, KumarP, Nayyar PV, Singh A. Botox: broadening the horizon of dentistry. J ClinDiagn Res. 2014;8:25–29.

- DentistryIQ.AAFE prepares courses for Hygienists Allowed to Treat with Dermal Fillers inNevada. Available at:?dentistryiq.com/articles/2015/12/nevada-allows-dental-hygienists-to-treat-with-facial-injectables.html. AccessedOctober 18, 2017.

- AmericanAcademy of Facial Esthetics. Nevada Becomes First State to Allow DentalHygienists To Use Facial Injectables. Available at:facialesthetics.org/blog/nevada-becomes-first-state-to-allow-dental-hygienists-to-use-facial-injectables.Accessed October 18, 2017.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. November 2017;15(11):46-49.