CE Sponsored by Philips: Providing Ethical, Culturally Competent Care

Oral health professionals are charged with encouraging open communication with patients, and understanding their perception of health and disease, as influenced by traditional beliefs.

This course was published in the November 2017 issue and expires November 2020. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Explain key tenets of ethical and culturally sensitive patient care.

- Describe the factors that shape health beliefs, and patients’ perceptions of oral disease and treatment.

- Provide culturally competent therapy in clinical settings.

INTRODUCTION

It is our responsibility as oral health professionals to treat every patient with ethical, culturally competent care. Philips is a health technology company that cares about people and delivers meaningful innovation. We believe there’s always a way to make life better, and to achieve this positive impact we have teamed up with Dimensions of Dental Hygiene by providing an unrestricted educational grant supporting this excellent continuing education article by Pamela Zarkowski, BSDH, MPH, JD. An awareness and understanding of patients’ values and beliefs, along with cultural differences, help practicing oral health professionals best accommodate patients’ needs and concerns. We believe you will find this article helpful as you serve your diverse patient population and make their lives better.

—Cindy Sensabaugh, RDH, MSSenior Manager

Professional Education and Academic Relations

Philips Oral Healthcare

DELIVER CULTURALLY SENSITIVE CARE

Every dental patient seeks and deserves a quality, evidence-based and respectful experience. Each patient brings to the appointment a unique set of oral health needs and expectations. At the same time, each arrives with an individual understanding of his or her oral condition, health beliefs and practices. Using the ethical principles of autonomy, nonmaleficence, beneficence, and justice as a framework for patient interactions will help guide all facets of professional care.

Well trained in the assessment, diagnosis, planning, treatment, and evaluation of outcomes essential to oral health care, dental hygienists strive to provide ethically based treatment. The American Dental Hygienists’ Association (ADHA) Code of Ethics provides guidance to practitioners, and states that all individuals should have access to health care, including oral health care.1 The ADHA code also provides guidance concerning interactions with patients, and offers directives to serve all patients without discrimination, communicate in a respectful manner, and provide patients with the information necessary to make informed decisions. A key statement in the code encourages clinicians to recognize that cultural beliefs influence patient decisions.

In addition, the ADHA Standards for Clinical Dental Hygiene Practice, revised in 2016, emphasize that “dental hygienists are expected to respect diverse values, beliefs, and cultures present in individuals and communities.”2 The standards underscore the importance of communication in assisting patients in making informed decisions, and suggest the possibility of using an interpreter to support positive communication. The standards outline professional responsibilities and state that dental hygienists should understand and adhere to the ADHA Code of Ethics and incorporate cultural competence in all professional interactions.1,2 The standards also direct clinicians to consider patient diversity, cultural competence, cultural issues, and literacy when providing care. Recognizing the demographics of the patient populations served by the profession, both the ADHA Code of Ethics and Standards for Clinical Dental Hygiene Practice provide guidance for culturally sensitive care.1,2

Today’s patient population is diverse, and each individual brings to the provider/patient experience not only specific oral health needs, but also an expectation that diversity will be respected and understood. Oral health professionals must develop awareness so as to recognize each individual’s cultural diversity and health literacy. Culture influences a patient’s communication style, beliefs, understanding of health and disease, and attitude toward health care.3 Cultural competency is a set of skills, knowledge and attitudes that enhance a clinician’s understanding of—and respect for—a patient’s values, beliefs, and expectations.3 Health literacy is the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic information concerning health and services that is necessary to make appropriate health decisions.4

Today’s patient population is diverse, and each individual brings to the provider/patient experience not only specific oral health needs, but also an expectation that diversity will be respected and understood. Oral health professionals must develop awareness so as to recognize each individual’s cultural diversity and health literacy. Culture influences a patient’s communication style, beliefs, understanding of health and disease, and attitude toward health care.3 Cultural competency is a set of skills, knowledge and attitudes that enhance a clinician’s understanding of—and respect for—a patient’s values, beliefs, and expectations.3 Health literacy is the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic information concerning health and services that is necessary to make appropriate health decisions.4

Providers should take into consideration the culture of a patient, his or her ability to comprehend and synthesize information, and recognize the need to treat that individual in a professionally competent manner. Embracing the concepts of cultural competence, health literacy, and culture lays the foundation for cultural respect. The latter is defined as a combination of a body of knowledge, a body of belief, and a body of behavior.5 It involves a number of elements, including personal identification, language, thoughts, communication, actions, customs, beliefs, values, and institutions that are often specific to ethnic, racial, religious, geographic, or social groups.5 The provider of health information or health care must recognize these elements influence beliefs and belief systems surrounding health, healing, wellness, illness, and disease. The integration of cultural respect into daily practice has a positive effect on patient care by enabling providers to deliver services that are respectful of—and responsive to—the health beliefs, practices, cultural, and linguistic needs of diverse patients.5 Recognizing and embracing the importance of cultural respect directly contributes to improved care.

ETHICALLY BASED CARE

Patient care involves treating a broad spectrum of individuals described in many ways, such as diverse patient family, demographically diverse, or representative of the culture or cultures living in a specific community. Diversity can be broadly defined to include all aspects of human differences; for example, physical dimensions, including race, ethnicity, and cultural background. Diversity can also be described using other influencing factors, such as socioeconomic status, religion, place of birth, or educational achievement. Additional characteristics that contribute to diversity include age, mobility, disability, gender, gender expression, height, weight, or marital status. All of these factors influence a patient’s understanding and management of oral health.

In many situations, cultural background and experiences have a unique way of influencing oral and general health practices and beliefs. For example, many cultural groups are not prevention oriented, and only seek care when there is a serious problem. In this scenario, an individual will only seek care from an oral health professional after experiencing significant pain, with the expectation that the tooth will be extracted so the pain will be gone. In the United States and other Western cultures, suggesting a root canal and a restoration would be expected. However, the person experiencing the pain may view such treatment available only to the wealthy and not consider it as a viable option.6

A commitment to treating diverse patients and integrating their cultural beliefs and practices in assessment, treatment planning, and therapy is based on ethical principles. In turn, recognizing the emphasis on cultural respect in patient care heightens the need to practice in an ethical manner. The principles of autonomy, beneficence, justice, and veracity provide a foundation for managing patient interactions and care, and integrating cultural respect into all clinical care situations.

The principle of autonomy supports the patient’s role in independent decision making. A patient must be able to make an informed decision about the care he or she is to receive in order to allow the individual to self-determine a course of action. Communication plays a critical role. Appropriate communication and information collection enhance patient rapport and compliance. Obtaining informed consent for treatment is a legal obligation that is based on the ethical principle of autonomy. To be informed, the patient must understand the reasons for a recommended treatment, as well as the risks and benefits. The provider also has an obligation to inform the individual in a manner that recognizes the patient has his or her own belief system. The patient makes decisions based on the information that was provided under the context of the individual’s beliefs and practices.

By way of example, an oral health professional may observe the clinical signs of periodontal diseases, and collect and record clinical findings that support a diagnosis of advanced periodontitis. Following data collection and analysis, the provider offers a treatment recommendation and presents a plan for therapy. As a result of his or her beliefs, however, the patient may view the same condition differently. For instance, some cultures believe that periodontal conditions are related to a hot and cold syndrome, and that mixing the wrong combination of hot and cold foods will lead to poor oral health.6 A patient may attribute a particular condition to an imbalance in the individual’s life, or a consequence of a particular action. Other cultures value the esthetic appearance of teeth, but do not value having both healthy teeth and gingiva;6 in other words, red and bleeding gingiva is not perceived as a problem if the visible teeth look good.

As these examples demonstrate, beliefs impact a number of clinical issues, including when a patient seeks care, management of the condition, the treatment choices the individual elects, and, in some instances, how he or she follows or responds to specific recommendations or therapies. All of these considerations help shape the patient’s assessment of the options presented and, ultimately, influence informed consent.

The principle of beneficence motivates the provider to take steps to benefit the patient’s well being and oral health. An example of beneficence in clinical practice is assessing a patient’s dietary habits to determine what may be contributing to an increase in caries. In this case, understanding that diet is influenced by culture is important. Food plays a significant role in many cultures, whether as a form of sustenance, custom, or celebration. A dental team member recommending a reduction in sugar intake may not recognize that sweets are an important part of a culture’s regular diet, and that reducing or eliminating that food product is not an option due to cultural practices.

The principle of justice means treating patients fairly. Although a clinician might not consciously want to treat someone in an unfair manner, if the provider does not consider the cultural, religious, or ethnic background of the patient when planning care, or assumes that every patient follows the same health philosophy as the provider, there is a possibility the patient will be treated unfairly. Practitioners cannot assume that each patient has adopted the same health beliefs and practices, as culture, socioeconomic factors, generational practices, and religious requirements all contribute to different perspectives. Patients may be unfamiliar with oral health practices for preventing caries or periodontal diseases. Some cultures rely on folk remedies or family traditions to address oral health conditions, such as soaking a cotton ball in clove oil and dabbing it on the tooth. Other cultures believe that a painful tooth is a result of the body harboring excess heat, or from the flow of energy being inhibited. Acupuncture may be the treatment of choice to address the pain. Providers must not make assumptions about patients, whether positive or negative, because of their values, practices, or beliefs.

The principle of veracity demands truthfulness. Oral health professionals cannot hesitate to be honest with patients and explain that an action they are taking to address an oral condition may be harmful. For example, if used to treat tooth pain, a culturally based practice, such as coin rubbing therapy, may appear as a bruise or abrasion on the face or neck. Coin rubbing is a global alternative medicine practice that uses special oil or ointment and rubbing the coin in a linear pattern until a skin abrasion occurs on the affected area. Ignoring a discolored or bruised portion of the face that may be near an area of the oral cavity in which there is caries or an infection is not being truthful with the patient.

Alternately, if the clinician does not ask about the source of the bruising, he or she may incorrectly assume the bruise is the result of an abusive situation. Ignoring or not seeking additional information about home remedies or alternative treatments the patient may have used prevents providers from demonstrating sincerity and trustworthiness, thus violating the ethical principle of veracity. Clinicians must also be truthful in educating the patient that home remedies or alternative therapies might negatively impact the professional treatment being rendered.

CULTURAL PERCEPTIONS

The ethical principles of autonomy, beneficence, justice, and veracity must be translated into action by the oral health professional. During interactions with a patient, when collecting health history, and when suggesting treatment or evaluating outcomes, the provider must be sensitive to the patient’s health care beliefs. Patients may define and categorize health and illness in a variety of ways. The illness may be attributed to an evil force that is retaliating for moral or spiritual failings, and/or violations of social norms or religious taboos. Or it may be attributed simply to bad luck or karma.

Some cultures view health in relation to maintaining balance by regulating one’s diet according to the seasons. For example, a patient may believe that a specific illness is the result of an imbalance in one’s life, or that the condition may be the result of other factors, such as a test of character. Patients may not value Western medicine solutions to a particular condition, but, rather, seek alternative therapies based on their own cultural beliefs and practices. A provider can gather insight into a patient’s beliefs by asking questions and making sure their assessment protocol includes questions about the specific condition, treatments used by the patient, and any healers that have been consulted.

TREATMENT STRATEGIES

For practitioners, the challenge is to balance ethical principles and the need to meet the standard of care within the context of a patient’s cultural beliefs. Any clinicians practicing within a community that has a large population from a specific culture is advised to learn about that culture’s health beliefs and practices. The provider must assign priority to each patient’s autonomy and ability to determine care. Designating autonomy as a priority translates to valuing informed consent and taking steps to partner with the patient in the treatment planning process by recognizing the patient’s beliefs, practices and values. This requires meaningful communication, shared decision making, and participation by both the provider and patient in the treatment planning and informed consent process. The emphasis should be on educating patients about their choices.7

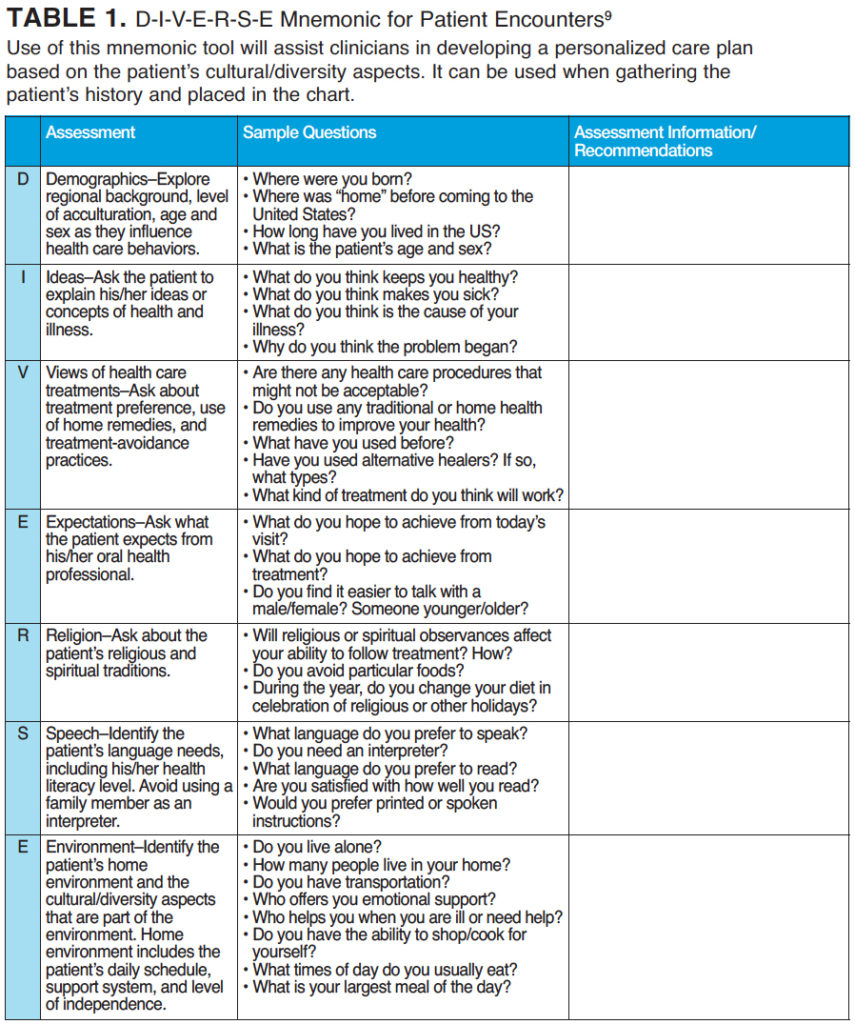

To enhance shared decision making, providers must identify areas where cultural differences may be an issue; develop awareness of one’s own values, biases, and understanding; and develop a nonbiased, nonjudgmental stance.8 Clinicians must recognize that diverse patients have different communication needs—including the pace of speech, volume, and sensitivity to body language and eye contact. Another strategy that enhances communication is using a series of questions that will provide the clinician with information about the patient’s culturally based health care beliefs and practices. The D-I-V-E-R-S-E Mnemonic for Patient Encounters (Table 1) provides a framework for seeking information that will assist in patient assessment and support culturally respectful care and the ethical principles that guide such care.9

Health literacy is also a factor that must be considered in patient communications. Practitioners should not assume that all culturally diverse patients have low health literacy; however, they should monitor behaviors that may indicate low health literacy, such as an inability to answer questions or complete health forms, noncompliance with specific recommendations, postponing decision making, or making excuses for delaying treatment. Oral health professionals can incorporate a number of strategies to assist patients with low health literacy. Speaking slowly, showing pictures, and utilizing the tell-show-do technique (to confirm that patients understand what they have been told) are all useful techniques.

A simple approach to evaluating health literacy is to ask the patient, “When you go home, tell me what you will tell your spouse about the directions I gave you concerning your premedication.” Using plain language is also helpful, as this makes written and oral information easier to understand. An important tool for improving health literacy, plain language is communication that patients can understand the first time they read or hear it. It is sometimes referred to as “living room” language, and is a technique that clinicians use to explain oral conditions in simple, understandable language. This technique is very useful for patients from a wide variety of backgrounds. In terms of written materials, a plain language document is one in which people can find what they need, understand what they find, and act appropriately on that understanding.10 Plain language documents can be developed to explain oral health conditions and their treatment, post-operative directions, or habits that are harmful to oral health.

CONCLUSION

While a practitioner may work in a practice, clinic, or community-based center with a patient population that represents a wide range of diversity, one cannot possibly understand all the cultural beliefs or practices due to sheer variety of patients. However, they can use models that serve as a framework for interacting with patients. For example, Ask Me 3 is an effective tool that suggests three simple, but essential, questions that patients should ask their providers.

- What is my main problem?

- What do I need to do?

- Why is it important for me to do this?

Ask Me 3 is intended to help patients become more engaged with their oral health and medical providers. These questions improve communications between patients, families, and health care professionals. Resources are available for dental offices and include brochures, posters, and a website about health literacy.11

In order to provide ethical, culturally competent care, clinicians must recognize the diversity of the patients seeking treatment. Respecting cultural diversity means communicating with patients to determine their health beliefs, and understanding their perception of health and disease as influenced through their own cultural lens. Beyond the strategies explored in this article, further resources and tools exist to assist oral health professionals in providing culturally respectful care to all patients.

REFERENCES

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association. Bylaws and Code of Ethics. Available at: adha.org/resources-docs/7611_Bylaws_and_Code_of_Ethics.pdf. Accessed October 3, 2017.

- American Dental Hygienists Association. Standards for Clinical Dental Hygiene Practice. Available at: adha.org/resources-docs/2016-Revised-Standards-for-Clinical-Dental-Hygiene-Practice.pdf. Accessed October 3, 2017.

- Spector RE. Cultural Diversity in Health and Illness. 9th ed. New York, NY: Pearson; 2017.

- Health Resources and Services Administration. Culture, Language and Health Literacy. Available at: hrsa.gov/culturalcompetence/index.html. Accessed October 3, 2017.

- National Institutes of Health. Clear Communication: Cultural Respect. Available at: nih.gov/institutes-nih/nih-office-director/office-communications-public-liaison/clear-communication/cultural-respect. Accessed October 3, 2017.

- Carteret M. How Culture Affects Oral Health Beliefs and Behaviors. Available at: dimensionsofculture.com/2013/01/how-culture-affects-oral-health-beliefs-and-behaviors/. Accessed October 3, 2017.

- Donate-Bartfield E, Lobb WK, Roucka TM. Teaching culturally sensitive care to dental students: a multidisciplinary approach. J Dent Educ. 2014;78: 454–464.

- Betancourt JR. Cultural competence and medical education: many names many perspectives, one goal. Acad Med. 2006;81:499–501.

- Anthem Blue Cross. Caring for Diverse Populations—Better Communication, Better Care: A Toolkit for Physicians and Health Care Professionals. Available at: anthem.com/ca/provider/f3/s1/t0/pw_b144192.pdf?refer=agent. Accessed October 3, 2017.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Plain Language Materials and Resources. Available at:cdc.gov/healthliteracy/developmaterials/plainlanguage.html. Accessed October 3, 2017.

- Institute for Health Care Improvement and National Patient Safety Foundation. Ask Me 3: Good Questions for Good Health. Available at: npsf.org/?page=askme3. Accessed October 3, 2017.

Featured photo by JABEJON/E+/GETTY IMAGES

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. November 2017;15(11):37-42.