SNEKSY / ISTOCK

SNEKSY / ISTOCK

The Importance of Health Literacy

The Importance of Health Literacy Patients with low health literacy need targeted interventions to support successful treatment outcomes.

This course was published in the November 2015 issue and expires November 20, 2018. The author has no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Define health literacy.

- Discuss why health literacy is important.

- Explain the indicators of and risk factors for low health literacy.

- List resources and strategies for improving verbal and written communication.

Dental hygienists are on the frontline of prevention. They are often the first oral health professional to review patients’ medical histories, obtains vital signs, complete assessments, and provide dental hygiene diagnoses. As such, dental hygienists need to equip themselves with the skills needed to advance positive oral health outcomes. Supporting patients with low health literacy is key to helping them maintain and/or improve their oral health.

Health literacy is defined as the ability to obtain, process, and understand the health information necessary to make informed health decisions.1 This is not simply the ability to read; rather, health literacy requires a complex mix of reading, listening, analytical, and decision-making skills and the ability to apply these skills to health situations.2,3 This skill set includes the ability to interpret documents, read and write prose (print literacy), use quantitative information (numeracy), and speak and listen effectively (oral literacy).4

EFFECTS OF LOW AND LIMITED HEALTH LITERACY

Limited health literacy can interfere with the efficacy of prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of disease. In 2003, approximately 80 million adults in the United States (36%) had limited or poor health literacy.5–7 Rates of poor health literacy were significantly higher among older adults, minorities, individuals without a high school diploma, adults for whom English is a second language, and those of low socioeconomic status.2,6–9 These populations face barriers to attaining the information needed to make well-informed decisions about their health.10–12 Low health literacy is also related to patients’ lack of familiarity with medical terminology and basic human anatomy; limited ability to analyze and interpret risks that affect their health and safety; and reduced comprehension of diagnosis and treatment outcomes.4,13

Besides the impact on health outcomes, low health literacy is also expensive. Horowitz and Kleinman14 report that low health literacy costs the US between $106 billion and $238 billion each year, representing 17% of personal health care spending.

THE DENTAL COMPONENT

Health literacy is an issue in dentistry as well. Three major policy documents describe the problem and suggest ways to improve it: Oral Health in America released by the US Surgeon General, Healthy People 2010 published by the US Department of Health and Human Services, and A National Call to Action to Promote Oral Health produced by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research.15–17 These reports emphasize disparities in dental health and suggest that low health literacy may result in poor oral health outcomes.15 Healthy People 2010 in particular highlighted the epidemic of oral diseases affecting pediatric, geriatric, and racial/ethnic minority populations and called upon health care professionals to take action.16

One of the goals of Healthy People 2010 was to change patients’ perceptions about oral health, as it has often been seen as separate and less important than overall health. This directive has inspired action to increase health literacy. Oral health professionals, including dental hygienists, should strive to improve health literacy in order to boost overall health outcomes.17 A continuation of the first initiative, another program was established—Healthy People 2020—that suggested improvement of health communication strategies would positively impact population health outcomes and overall health care quality.12

A significant barrier to effective communication in the dental setting is clinicians’ inability or difficulty in addressing patients’ literacy needs.10 Thirty-six percent of American adults have intermediate health literacy scores.4,18 Patients with low health literacy scores are more afraid to ask questions and request information when presented with a dental and/or dental hygiene treatment plan than individuals with higher scores.5,19 Low health literacy also contributes to other barriers to improved health, such as the cost of care, access to care, the complexity of health care systems, and lack of insurance coverage.20

INDICATORS AND RISK FACTORS FOR LOW HEALTH LITERACY

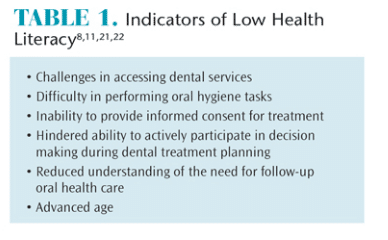

Many signs of low health literacy are easily identified by dental hygienists or other members of the dental team.21 Table 1 provides a list of indicators.8,11,21,22 Patients with low health literacy often show little or no interest in written communication such as pamphlets or health history forms.21 They often express frustration or impatience when encouraged to use printed materials.23

Many signs of low health literacy are easily identified by dental hygienists or other members of the dental team.21 Table 1 provides a list of indicators.8,11,21,22 Patients with low health literacy often show little or no interest in written communication such as pamphlets or health history forms.21 They often express frustration or impatience when encouraged to use printed materials.23

Oral health professionals need to be able to assess patients’ health literacy so that verbal instructions and patient materials can be matched to patients’ literacy skills. Clinicians may also opt to use to nonprinted teaching materials, such as videos, audiotapes, and demonstrations, to ensure their messaging is understood.23 Assessing patients health literacy skills can be challenging. A screening test called Newest Vital Sign is available and is quick, accurate, and bilingual (English and Spanish). It assesses general literacy, numeracy, and comprehension skills and is designed for use in primary care settings.24 Another way to evaluate and screen for low health literacy is to ask patients to read their prescription bottles and then explain how to take their medications.14 When considering the use of a health literacy test, clinicians must be sensitive to their patients’ feelings. If literacy testing is suggested, patients may feel shame and alienation, which may discourage them from returning for additional treatment.24,25

Older adults are at increased risk of low health literacy. Reading ability scores decline considerably after age 55.21 Many older adults have experienced varying degrees of auditory, visual, or cognition losses that affect health literacy levels. Furthermore, differences in generational cultures can also impact communication with health care providers.21,22

Cultural differences may also adversely affect communication in the dental setting.26 Patients from different cultures may involve their whole family in health-care decision making. Additionally, cultural attitudes regarding gender and status of health care providers may prevent patients from asking questions related to their health or treatment. Language barriers may exist. In such cases, a medical interpreter should be engaged. Providing written materials in patients’ language of origin is also helpful. Providing culturally competent care can help improve health literacy.5,14

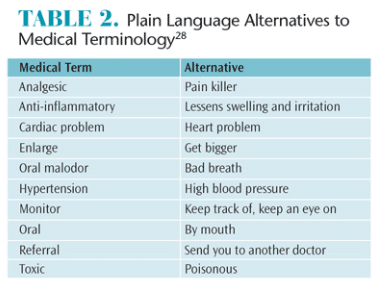

Most patients are not intimately familiar with anatomy or medical terminology, but for patients with low health literacy, these deficits can prevent them from receiving much needed care.27 Dental hygienists are fluent in medical terminology and may need to self-remind to use more general terms. Table 2 provides alternative terminology for common medical vernacular.28

RESOURCES FOR IMPROVING HEALTH LITERACY![]()

The resources available to improve health literacy are based on the main factors that contribute to it: culture and ethnicity, age, education level, and language.1 While culture and ethnicity are only a part of health literacy, they are important pieces of a complicated issue. Recognizing that culture plays an important role in communication provides clinicians with a better understanding of health literacy.18

Many educational materials on health are written at levels beyond the skills of an average high-school student.29 Clinicians need to search out print and nonwritten materials or create their own that provide education in a clear and concise manner. The information needs to be delivered in plain language that is easy to understand.18 Print, audio, computer applications, and video can all be used to provide patient education.18,30

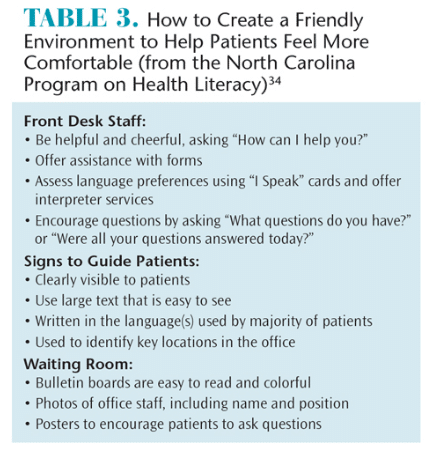

The American Medical Association, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and Health Resources and Services Administration provide tools and education for health care providers to support their efforts in improving the health literacy of their patients.31–33 Table 3 provides an example of suggestions to make a health care or dental office more inviting to patients with varying levels of health literacy.34

STRATEGIES FOR DENTAL HYGIENISTS

Dental hygienists can significantly impact the oral health outcomes of their patients.22 They are well positioned to note low health literacy skills and to take action to ensure patients fully understand their treatment needs.21 Dental hygiene appointments provide patients with opportunities to ask questions, learn the skills required for effective self-care, and receive additional information on health promotion strategies. The skills needed for health literacy include evaluating information for quality, analyzing risks and benefits, calculating doses, interpreting test results, and locating health information.29 Therefore, dental hygienists need to focus their efforts toward improving these skills.

Information initially given to patients should be limited to what they need to know in order to prevent overwhelming patients. Clinicians should focus on the most important three points to five points to aid in comprehension of the information.21

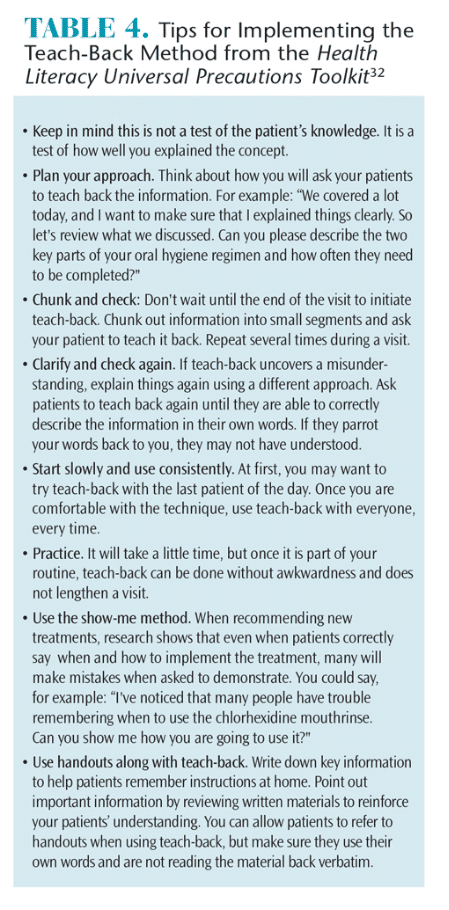

The teach-back technique is a useful tool to ensure that patients understand the instructions provided. In this method, practitioners confirm whether patients understand what was communicated by asking them to repeat the information in their own words.21 This technique also helps clinicians assess patients’ comprehension levels and whether the information was provided in a clear and concise manner.20 Table 4 provides additional information on implementing the teach-back method.32

Dental hygienists can also participate in professional development activities on the importance of health literacy.35 These may include receiving additional training in effective patient communication techniques and ensuring that educational materials are written at an appropriate reading level. Additionally, dental hygienists should encourage and educate all team members to recognize and respond appropriately to patients with literacy and language deficits.35,36

CONCLUSION

Patients’ health literacy is a stronger predictor of their health status than income, employment, education level, and racial or ethnic group.19 Low health literacy, once identified, can be effectively addressed and managed to improve overall health outcomes. A necessary component of health care decision making, health literacy impacts patients’ abilities to be engaged in their own health management. Low health literacy is a barrier to effective patient-provider communication and the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of disease. The ability to recognize health literacy issues enables dental hygienists to improve patient communication and education and find alternative strategies for engaging patients in health management.

REFERENCES

- Nutbeam D. The evolving concept of health literacy. Soc Sci & Med. 2008;67:2072–2078.

- Berkman ND, Davis TC, McCormack L. Health literacy: What is it? Health Commun. 2010;15(Suppl):9–19.

- Rudd RM. Health literacy skills of U.S. adults.Am J Health Behav. 2007;31:8–18.

- Health Literacy Interventions and Outcomes: AnUpdated Systematic Review. Executive Summary.Rockville, Maryland: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2011:AHRQ 11-E006-1.

- Berkman, ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE,Halpern DJ, Crotty K. Low health literacy and health outcomes: an updated systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:94–41.

- Andrulis DP, Brach C. Integrating literacy,culture, and language to improve health care quality for diverse populations. Am J Health Behav. 2007;31(Suppl):122–133.

- Schonlau M, Martin L, Haas A, Pitkin-Derose K,Rudd RM. Patients’ literacy skills: More than just reading ability. J Health Commun. 2011;16:1046–1054.

- Bennet IM, Chen J, Soroui JS,White S. The contribution of health literacy to disparities in self-rated health status and preventive health behaviors in older adults. Ann Fam Med.2009;7:204–211.

- Smith SG, O’Conor R, Curtis LM.Low health literacy predicts decline in physical function among older adults: findings from the LitCog cohort study. J Epidemiol Commun Health.2015;69:474–480.

- American Dental Association, Council on Access,Prevention and Interprofessional Relations Health literacy in dentistry: Action plan 2010-2015. 2010. Available at nationaloralhealthconference.com/docs/presentations/2010/Gary%20Podschun%20-%20National%20Plans%20to%20Improve%20Health%20Literacy.pdf. Accessed October 20, 2015.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.Older adults: Why is health literacy important?Available at: cdc.gov/healthliteracy/ develop materials/audiences/olderadults/importance.html.Accessed October 20, 2015

- US Department of Health and HumanServices. Healthy People 2020. Washington, DC:Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; 2010: publication no. B0132.

- Divaris K, Lee JY, Baker AD, Vann WF. The relationship of oral health literacy with oral health-related quality of life in a multi-racial sample of low-income female caregivers. HealthQual Life Outcomes. 2011;9:1–9.

- Horowitz AM, Kleinman DV. Oral healthliteracy: The new imperative to better oral health.Dent Clin North Am. 2008;52:333–344.

- US Department of Health and HumanServices, Oral Health in America: A report of theSurgeon General-Executive Summary. Rockville,Maryland: National Institute of Dental andCraniofacial Research; 2000.

- US Department of Health and HumanServices. Healthy People 2010: Understanding andImproving Health. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; 2000.

- A National Call to Action to Promote OralHealth. Rockville, Maryland: US Department ofHealth and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research. 2003; NIH Publication No. 03-5303..

- Weiss BD. Removing Barriers o Better, SaferCare. Health Literacy and Patient Safety: HelpPatients Understand. Manual For Clinicians. 2nd ed. Chicago: American Medical AssociationFoundation; 2009:6–43.

- Katz MG, Jacobson TA, Valedar E, Kirpalani S.Patient literacy and question-asking behavior during the medical encounter: A mixed-method analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:782–786.

- Horowitz AM. The role of health literacy inreducing health disparities. J Dent Hyg. 2009;83:182–183.

- Schiavo JH. Oral health literacy in the dentaloffice: The unrecognized patient risk factor. J DentHyg. 2011;84:248–255.

- Chalmers JM, Ettinger RL. Public health issues in geriatric dentistry in the United States. Dental Clin North Am. 2008;52:423–446.

- Cornett S. Assessing and addressing healthliteracy. Online J Issues Nurs. 2009;14:1.

- Shah LC, Bremmeyr K, Savoy-Moore RT. Health literacy instrument in family medicine: The“Newest Vital Sign” ease of use and correlates. J Am Board Fam Med. 2010;23:195–203.

- Paasche-Orlow M K, Wolf MS. Evidence doesnot support clinical screening of literacy. J GenIntern Med. 2007;23:100–102.

- Singleton K, Krause EM. Understandingcultural and linguistic barriers to health literacy.Online J Issues Nurs. 2009;14:2.

- Koh HK, Berwick DM, Clancy CM, et al. At theintersection of health, health care and policy.Health Aff. 2012;31:1–10.

- Taichman RS, Parkinson JW, Nelson BA, Nordquist B, Ferguson-Youn DC, Thompson Jr. JF.Program design considerations for leadership training for dental and dental hygiene students.J Am Dent Assoc. 2012;76:192–199.

- Rudd RE. Improving Americans’ health literacy.N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2283–2285.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.Health Literacy: Develop Materials. Available at:http://chicago.craigslist.org/nwc/fuo/5274511749.htmlcdc.gov/healthliteracy/developmaterials/resources.html. Accessed October 20, 2015.

- American Medical Association. Health LiteracyKit. Available at: ama-assn.org/ama/pub/aboutama/ama-foundation/our-programs/publichealth/health-literacy-program/health-literacykit.page? Accessed October 20, 2015.

- DeWalt DA, Callahan LF, Hawk VH, et al.Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit.Rockville, Maryland: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2010: AHRQ 10-0046-EF.

- US Department of Health and HumanServices. Effective Communication Tools ForHealthcare Professionals. Available at: hrsa.gov/publichealth/healthliteracy. Accessed October 20,2015.

- North Carolina Program on Health Literacy.Health Literacy Universal Precautions for PrimaryCare. Available at: nchealthliteracy.org/ toolkit/Cardio/quickstartdiace.pdf. Accessed October 20,2015.

- Jones M, Lee, JY, Rozier, GR. Oral healthliteracy among adult patients seeking dental care.J Am Dent Assoc. 2007;138:1199–1208.

- Stableford S, Mettger W. Plain language: Astrategic response to the health literacy challenge.J Public Health Pol. 2007;28:71–93.

- Reardon GT. Low oral health literacy: Anexclusive dream or dentistry’s target for advocacy?Compend Contin Educ Dent Suppl. 2010;31:184–189.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. November 2015;13(11):68–71.