The Foundation of Integrity

Understanding the three philosophical frameworks that support moral thinking will help dental hygienists enhance their ethical decision-making skills.

This course was published in the January 2014 issue and expires January, 2017. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Describe the role of ethical theories in ethical decision making.

- List and compare the three classic approaches to ethical theories.

- Discuss the application of ethical theory to dental hygiene practice.

Integrity is defined as an ethical stance that causes individuals to adhere to their own values.1 Identifying these values and how they are developed and fostered in dental hygienists before, during, and after the formal education process are key to encouraging ethical decision making. Each person is the product of his or her growth and development, with age, education, culture, religion, and life experiences influencing his or her judgment. When dental hygienists are called upon to make clinical judgments in professional life, personal opinions and/or beliefs may be challenged—and are often the source of the tensions that underlie ethical dilemmas. This article will introduce the foundations of ethical theory as they guide ethical decision making among individuals.

The role of ethical theories is to lay a foundation for understanding ethical decision making. A system of moral reasoning, or thinking, is important because it provides a frame of reference that can help an individual make morally appropriate responses to dilemmas faced in personal and professional life. Although multiple theories have been proposed to explain how people process their thoughts and actions when faced with problems and dilemmas, three broad-based philosophies are considered the classic approaches. The three philosophies that comprise ethical theory are consequentialism (utilitarianism), deontology (nonconsequentialism), and virtue ethics.1,2

CONSEQUENTIALISM OR UTILITARIANISM

Consequentialism looks at the end results of any particular act. It is predicated on the idea that the rightness or wrongness of any action is determined and justified by its consequences. In addition, the consequences of the act are judged in comparison with other possible acts that might be performed in the situation. Consequentialist thinking is always comparative because it aims to maximize good consequences (thus, diminishing harmful ones). The consequentialist considers the consequences and potential outcomes of each important alternative course of action before making a decision. Consequentialists believe that identifying and evaluating all the potential consequences will lead to the most favorable outcomes.

For example, a dental hygienist may observe that his or her employer routinely leaves overhangs on restored teeth. Because overhangs may negatively affect the patient’s periodontal health, the dental hygienist must determine what, if any, action to take. He or she begins by identifying the alternatives and examining the benefit or harm that will most likely result from each one. First, the dental hygienist could take no action. One consequence of inaction might result in some patients developing severe periodontal diseases and/or losing teeth. Second, the clinician could remove the overhangs. One consequence of this action would be enhanced oral health for the patient. In some states, however, removal of overhangs may be illegal for the dental hygienist to perform, and doing so would violate the state practice act and could put his or her licensure and professional reputation in jeopardy. Third, the dental hygienist could discuss with the employer the fact that overhangs are frequently present. The consequence could be that the dentist would restore teeth more carefully. However, another consequence might be that the dentist refutes the claim and tells the dental hygienist to stay out of his or her business. If the dental hygienist persists on the subject, the dentist may decide to terminate his or her employment. All of these are consequences to consider because they are important alternatives for the dental hygienist in this situation.3 Note that the consequential reasoning approach would require the dental hygienist to do what is good even when it might not be in his or her best interest. Being ethical is not always easy. On the other hand, another action not previously considered might maximize everyone’s best interests. This is why consequentialist thinking must involve a careful look at all of the alternative actions available. Consequences are carefully evaluated for good and bad before deciding which decision yields the maximum benefit.

John Stuart Mill was one of the most famous proponents of utilitarianism, a theory based on the consequentialist approach to decision making. He stressed that in consequentialist reasoning, every person affected by an action should be considered.1 His writing taught that the moral action is the one that maximizes good and minimizes harm when the consequences for every affected person are considered. Consequences may be debated on an individual basis, but utilitarianism stresses that they must be reviewed for all involved. Instances where utilitarian reasoning might be appropriate is when ethical matters must be decided (eg, by local or state government) that will affect large social systems, communities, or even nations. For example, when public health dental hygienists weigh the burdens and benefits of community water fluoridation, they are engaged in utilitarian reasoning.4 The expected consequence will be a benefit through caries reduction for individuals and entire communities. The benefit will be provided at a relatively low cost (or financial burden) and is available to all community members, regardless of social status and with no reasonable possibility of causing harm.

DEONTOLOGY OR NONCONSEQUENTIALISM

The expression deontological ethics is derived from the Greek word deon, meaning duty. Deontologists state that some actions are required by the rightness or wrongness of the action, regardless of the consequences of the action.1 Whereas consequentialists focus on the consequences of an act, deontologists argue that some acts are right or wrong independent of their effects (thus, the term nonconsequentialism). Some acts are right because they have a direct relation to some overriding duty, or they are wrong because they directly violate some overriding duty. For example, a deontologist might believe that a health care provider has a duty to tell the truth in all circumstances, and, therefore, has a specific duty to tell the truth to patients. With this view, a professional’s duty to tell the truth to a patient is not founded on the consequences of telling the patient the truth, but on the belief that an absolute duty exists never to lie or the patient is entitled by his or her fundamental right to receive the truth. According to deontology, moral standards exist independently of the particular circumstances of an action, and do not depend on consequences. Duty and the relation of a person’s actions to duty are the only relevant considerations.

Immanuel Kant is credited for establishing one of the most detailed deontological or nonconsequentialist theories of ethical thinking. Kant held that the test of any rule of conduct is whether it can be a duty for all human beings to act on—what he called a universal law or “categorical imperative.”1,5 Kant also stressed that all adult human beings are free, worthy of respect, and can choose their purposes and actions. Many deontological theories of human rights have been built by later thinkers on this basis. This particular school of thought has had a significant effect on biomedical ethics.6 It places primacy on the right of the individual to act autonomously—that is, to make his or her own decisions on the basis of his or her own values, goals, principles, and ideals. Autonomy is an important principle of health care ethics.

Kant’s test was called the categorical imperative, which means a rule or standard of conduct that is absolutely binding for all human beings under all circumstances to which the rule or standard applies. He held that some of the moral rules we are familiar with (eg, do not lie) have this character of overriding duty. Kant further categorized these rules or standards into “perfect duties” and “imperfect duties.” Perfect duties are always binding. Imperfect duties refer to moral obligations to act in certain ways, but leave it to each person to judge when and in what situation to fulfill the obligation. Thus, an example of a perfect duty requires one not to kill an innocent human being. The prohibition against murder is binding because it is right and directly connected to an overriding duty, not because of the consequences. According to perfect duty, one person cannot morally kill another person, even if such an act was the only possible way to save the lives of others. Not stealing is a perfect duty, while an obligation to help another person in need is an imperfect duty. Thus, while members of a society have an overriding duty to attend to the needs of others, those members are not obligated to try to meet everyone’s needs. It is a matter of moral judgment that a person must carefully make to determine for whom and in which situations to fulfill this duty. Kant’s categorical imperative is often compared to the golden rule, which advises individuals to “do unto others as you would have others do unto you.”

An example of the deontological approach as it applies to dental hygiene is that a dental hygienist has a duty to maintain patient confidentiality in the provision of oral health care. Besides sharing information appropriately with other health care providers, data acquired while providing patient care must remain private (unless the patient’s express permission has been granted). If an adult patient’s relative or a representative of an insurance company asks questions regarding the patient, confidentiality must be maintained. It is right because respect for others’ autonomy is an overriding duty, and a patient’s revelation of personal information to the dental hygienist for purposes of oral health care does not include permission to use it for any other purpose. If this philosophy were strictly held in health care, the public health reporting of communicable disease would be impermissible. Kant expanded his moral theory, however, to cover societal rules in ways that could make such reporting morally acceptable if one could reasonably argue that any rational person would want such information communicated to avoid harm to others.7

Though deontological thinking may appear simple at the start, it becomes complex when trying to determine what social standards could reasonably be willed by rational people as universal standards by which to live. No philosopher has ever claimed that moral thinking was simple.

VIRTUE ETHICS

Virtue or character refers to consistent patterns of perceiving, thinking, and acting rightly.1 A person cannot stop and carefully weigh possible actions in terms of ethical standards hundreds of times a day, even though many opportunities for action each day are ethically significant. Therefore, most actions are the product of one’s character, or the stable patterns perceiving, thinking, and acting that are part of one’s intrinsic nature. If those patterns are perceiving, thinking, and acting rightly, they are called virtues—and those who demonstrate such qualities would be viewed as having good character. Within the context of a profession, these stable patterns of perceiving, thinking, and acting in accord with the profession’s ethical standards are referred to as “professionalism.” Hence, character and virtue are central themes in any discussion of ethics for professionals.8

Virtue ethics was first articulated as an ethical theory in the Greek tradition of Plato and Aristotle, who emphasized that the cultivation of virtuous traits of character is the primary function of morality. Aristotle wrote that virtue is a stable state of character and is the result of practice—that virtue is something acquired by a person through learning, reflection, and repetition. When trying to describe the virtues of good people, he looked for a balance between intellect and commitment in action. He also stressed that the person who is virtuous has developed the ability to perceive, judge, and act rightly as a dependable habit. The ideal habit is stability, allowing the virtuous person to act in a virtuous manner in all situations. Aristotle also recognized that each human being is fallible in achieving this ideal, and stressed the value for people to identify role models from whom they can learn, thus becoming more virtuous by doing right in each situation.

Each of the virtues is a habitual disposition to perceive, judge, and act rightly. Virtue ethics focuses not so much on the rightness or wrongness of a given act or whether it conforms to duty, but rather on the goodness of the person who habitually chooses to act in that way or see such acts as proper responses to duty.5 Rather than focusing first on consequences or nonconsequentialist factors such as duty or rights, philosophers of the virtue ethics tradition urge people to reflect on what kind of person they ought to be—and not the ethical characteristics of the acts they do. A dental hygienist could treat a hostile and unhappy patient with extra kindness and caring to maximize good and reduce harm because he or she considers it a duty. But in daily professional life, a dental hygienist or dentist will more likely do this to exercise their professionalism.9 A second example of acting with virtue in dental hygiene practice is the dental hygienist who automatically codes and bills for the service that was delivered even though he or she may have the opportunity to up-code and collect a larger fee. The practice of coding truthfully and accurately is habitual and done without second thought. In this regard, while it may seem strange to think of truthful behavior as virtuous, such a practice would meet the definition of virtue.

Virtue ethicists believe that individuals make most of their choices on the basis of virtue and character. The focus is on the character of the person. If a person has good character, that person will make choices that produce good. In an ideal world, of course, all people would be of good character and would make good choices easily and habitually in every situation. It is not likely that most people have completely arrived at that point. Even if, speaking ideally, all people of good character had good ethical decision-making abilities, one would have to work to develop these abilities and then make them into habitual patterns of perceiving, judging, and acting.

COMPARING THE THEORIES

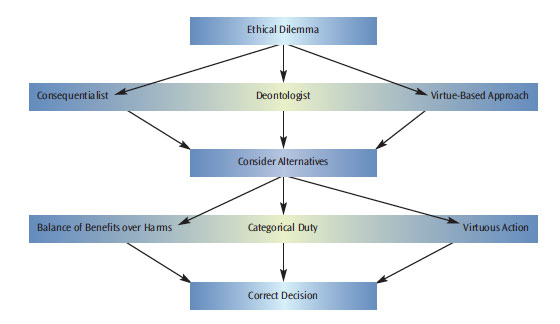

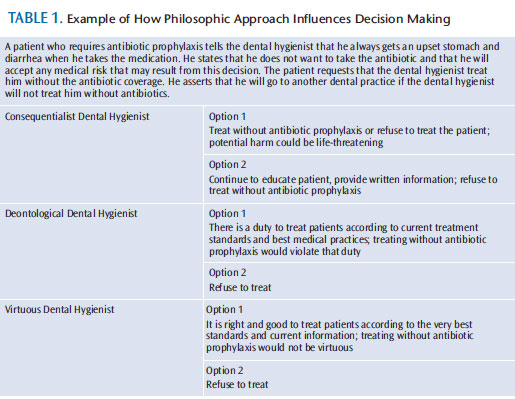

Three different approaches to ethical decision-making have been presented, and the dental hygienist may wonder how each one can be applied to lead to a correct decision in a particular case. Figure 1 presents the steps leading to a decision for each theory. Table 1 presents the application of each theory to an ethical dilemma in dental hygiene practice.

CONCLUSION

Consequentialism (utilitarianism), deontology (nonconsequentialism), and virtue ethics are three ethical theories that assist in making good moral decisions. Rarely does a person embrace one ethical philosophy exclusively. More than likely, an individual is influenced by more than one ethical system, as well as by a number of other factors, including religion, culture, and environment. However, knowledge of these philosophical frameworks for ethical thinking helps health care professionals understand their professional commitments more clearly, thus enhancing their interactions with patients and co-workers. The professions of dental hygiene and dentistry need thoughtful people of good character who can—as a result of education, experience, and careful reflection—enhance their skills in ethical decision making and act accordingly.

REFERENCES

- Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. 7th ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2012.

- Veatch RM. The Basics of Bioethics. 2nd ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 2002.

- Beemsterboer PL. Ethics and Law in Dental Hygiene. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2010.

- Welie JVM. Justice in Oral Health Care. Milwaukee: Marquette University Press; 2006.

- Ozar DT, Sokol DJ. Dental Ethics at Chairside: Professional Principles and Practical Applications. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press; 2002.

- Kant I. Kant: Critique of Practical Reason. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 1997.

- Rule JT, Veatch RM. Ethical Questions in Dentistry. 2nd ed. Hanover Park, Ill: Quintessence; 2004.

- Veatch RM, Haddad AM, English DC. Case Studies in Biomedical Ethics. New York: Oxford University Press; 2010.

- Rule JT, Bebeau M. Dentists Who Care: Inspiring Stories of Professional Commitment. Hanover Park, Ill: Quintessence; 2005.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. January 2014;12(1):52–54,57–58.