The Dangers of Tickborne Diseases

Lyme disease and other tickborne diseases can have devastating health effects, making early diagnosis critical.

This course was published in the February 2015 issue and expires February 2018. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Discuss the prevalence of Lyme disease.

- Identify the clinical manifestations of Lyme disease.

- List the treatment options for tickborne diseases.

- Note other tickborne diseases that can cause negative health effects.

The return of spring and warm weather will find many people spending more time outdoors. While exposure to nature provides many health benefits, caution should be exercised due to the risk of tickborne diseases. Tick exposure was once concentrated in the Northeastern part of the United States, but tick season is now a nationwide concern, especially during summer months. As people travel, recreate outdoors, and build homes in rural areas, exposure to ticks increases. Individuals residing in urban areas are not without risk, as ticks are adaptive and can be found in open fields, parks, and vacant lots. Health care professionals should be well versed in tickborne diseases so they can effectively educate their patients and note any signs and symptoms of these illnesses. Some tickborne diseases exert symptoms in the oral cavity, making dental professionals key in their early diagnosis.

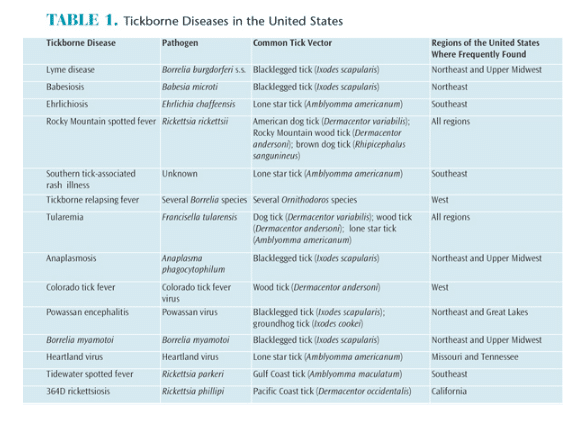

The American Lyme Disease Foundation reports there are approximately 30 major tickborne diseases and more than 850 tick species worldwide, of which 82 species are currently found in the US.1 According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 14 tickborne diseases have been identified in the US, including ehrlichiosis, transmitted by the lone star tick; Rocky Mountain spotted fever, from the American dog tick; Colorado tick fever, from the wood tick; and Tidewater spotted fever, from the Gulf Coast tick (Table 1).2 For the past two decades, Lyme disease has been the most common vector-borne illness in US.2,3

In the late 1970s, Lyme disease was virtually unknown. Originally termed Lyme arthritis, Lyme disease was first documented when a group of children living near Lyme, Connecticut, became ill with arthritis-type symptoms. In the early 1980s, the bacterial pathogen Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto species complex was identified as the causative agent.3 Ticks are disease vectors, attaching and feeding on the host and becoming engorged with the host’s blood, as well as the bacteria present in the host. Not all tick bites cause Lyme disease; only the blacklegged tick is associated with this condition. Blacklegged ticks can become infected while feeding on hosts such as mice, squirrels, and other small vertebrates. During subsequent blood meals, the tick transmits the bacteria to secondary hosts, including humans. Although deer cannot be infected with B. burgdorferi, they play a significant role in the reproductive success and transportation of the tick population. A single deer may carry and transfer between 200 ticks and 400 ticks. Each female blacklegged tick can lay up to 2,000 eggs.

The prevalence of Lyme disease is difficult to determine because many cases go unrecognized or are misdiagnosed. The condition could be underreported anywhere from 10 fold to 1,000 fold. From 1995 to 2013, the number of confirmed cases of Lyme disease ranged from a low of 11,700 in 1995 to a high of 29,959 in 2009, according to the CDC.4 In an effort to provide more accurate reporting, the CDC is undertaking studies to help estimate the total burden of Lyme disease from three different evaluation methods: medical claims, positive laboratory tests, and data on diagnosed cases. Preliminary results suggest that the number of people diagnosed with Lyme disease annually may be as high as 300,000.5

Most Lyme disease cases are reported in spring, summer, and early fall, when the immature stages of the blacklegged ticks are actively seeking hosts and people are more active outdoors. Lyme disease cases are concentrated geographically, with 95% reported in 14 states (Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, Massachusetts, Maryland, Minnesota, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Vermont, Virginia, and Wisconsin). Cases have been confirmed in all states except Colorado, Arkansas, and Hawaii.6 Another quandary is that the incidence of Lyme disease is reported by state of residence, whereas many people are actually infected while traveling outside of their home states.

TICK LIFE CYCLE

The life span of ticks varies from 2 years to 3 years. Blacklegged ticks have a four-stage life cycle: egg, larvae, nymph, and adult. Ticks feed only once per stage, and male ticks of some species rarely feed and never engorge. Flat, unfed ticks attach to the host and engorge on a blood meal. The transmission of bacteria from the tick to the host comes from the saliva of the infected tick and is disseminated through the host’s blood or tissue to other locations. During the feeding process, ticks will concentrate ingested blood by returning much of the water and salts to the host; thus, alternating periods of sucking blood and salivation with regurgitation occur. Once the infected tick is attached, the chances of transmission of B. burgdorferi increase with time: 0% at 24 hours, 12% at 48 hours, 79% at 72 hours, and 94% at 96 hours.7 Hence, the sooner the infected tick is discovered and removed, the better the outcome.

On average, ticks feed for 3 days as a larva, 5 days as a nymph, and 7 days as an adult before they release from the host. For the next 6 months to 12 months, the tick will remain in leaf litter or soil digesting the blood until it molts into the next life stage, at which time it will emerge for another blood meal.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Lyme disease is recognized as a multisystem vector-borne disease. Changing and intermittent signs and symptoms may complicate the diagnosis. Lyme disease is often referred to as the “great imitator” because it mimics diseases such as arthritis and multiple sclerosis. Clinical and systemic manifestations may appear as early as 3 days after the tick bite, but in some cases latent signs do not manifest until months or even years later. Mild forms of Lyme disease are easily treatable with antibiotics, while severe infections can require hospitalization. In the early stage (3 days to 30 days post-tick bite), the classic sign of the “bull’s-eye” skin rash, or erythema migrans, appears in approximately 70% to 80% of patients. The rash may be warm, but it is rarely painful or itchy. The rash, which appears near the site of the bite, can expand gradually over a period of days and parts of the rash will clear, resulting in the bull’s-eye appearance (Figure 1). This rash is extremely difficult to distinguish on nonwhite skin tones; thus, other symptoms should be considered. Additional signs of Lyme disease include: fatigue; headache; fever; chills; stiff neck; muscle aches; pain and swelling in large joints, such as knees; paralysis on one or both sides of the face; and enlarged lymph nodes. In later stages, the nervous system and heart may be affected.

In some cases, Lyme disease-associated facial paralysis may be confused with other neurological disorders, such as Guillain-Barre syndrome or Bell’s Palsy. The CDC reported that clinical manifestations of Lyme disease-associated Bell’s Palsy were evident in 9% of confirmed cases from 2001 to 2010.8 Persistent musculoskeletal Lyme disease-associated arthritis may also mimic or trigger fibromyalgia. Symptoms of fibromyalgia, however, cannot be cured with antibiotics. In many cases, people thought to have fibromyalgia actually have Lyme disease, and vice versa. Although most Lyme disease-related joint pain and swelling are associated with large joints in the knees and hips, the joint first affected may not correlate to the site of the initial skin lesion or tick bite. Temporomandibular joint (TMJ) pain also has been linked to Lyme disease.9,10

Changing symptoms of Lyme disease present a diagnostic dilemma. The manifestation of the bull’s-eye rash, large joint involvement, fatigue, chills/fever, and headache are common signs; however, less common symptoms, such as TMJ pain and facial paralysis, may be the first problems experienced. These signs may bring affected individuals to the dental office.

DIAGNOSIS

Because differential diagnosis for Lyme disease is challenging, two-tiered testing is recommended.11–14 The first tier consists of a blood test, known as the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay or enzyme immunoassay, that will detect antibodies. If the test is negative, no further testing is recommended. If the result is positive or equivocal, the second tier of testing, known as the Western blot test, should be performed. After an individual is infected, it can take several weeks to produce a positive laboratory result. This explains why individuals who experience a reddish expanding bull’s-eye rash may have negative test results in the early stages of the disease. Frequently, physicians use the high prevalence of Lyme disease or tick encounters within a community as an additional diagnostic tool.

TREATMENT

Treatment options are based on the stage of the disease and whether the infected individual is a child, adult, or pregnant woman. The serological testing used to diagnose the disease and the prophylactic administration of antibiotic therapy are controversial.13 To date, there is no standard, accepted treatment for Lyme disease, and there is no official recommendation for passive or active immunization after a tick bite. The blood test for detecting the presence of Lyme disease is more accurate the longer the disease has been present. Early treatment options include the oral or intravenous administration of doxycycline, amoxicillin, or cefuroxime for 2 weeks to 3 weeks.14,15

Lyme disease contracted during pregnancy may lead to infection of the placenta. Generally, pregnant women are treated similarly to other adults; however, certain antibiotics, such as doxycycline, are not recommended. If left untreated, Lyme disease can harm fetuses; therefore, pregnant women who have been in a high-risk environment, are bit by a tick, or present with equivocal symptoms should see a physician immediately.

PREVENTION

Tick inspections should be performed after working outside or recreating in tick-infested areas. Ticks are tiny and easily missed; therefore, rigorous daily tick checks are recommended. Before ticks feed, they may wander around the host for several hours, providing an opportunity to identify and remove the tick before it attaches to and penetrates the skin. Wearing personal protection, such as light-colored clothing, closed-toed shoes, tall socks, long pants, and long sleeves, will reduce the risk of being bitten. Pants or socks can also be taped around the ankles or legs to help prevent ticks from crawling under clothing. Long hair should be pulled back or tucked under a hat. Because ticks seek out exposed skin and can invade tiny spaces, individuals should shower as soon as they come indoors and check their entire bodies, especially tissue folds, armpits, and groin areas, for ticks.

Insect repellents containing 20% to 30% DEET (N,N-diethyl-meta-toluamide) provide the best protection (up to 5 hours) and should be applied on exposed skin, shoes, and clothing. The use of products that contain 0.5% permethrin on items such as clothes, shoes, socks, tents, and other gear can provide additional defense. As an added precaution, clothes that have been worn outside should be put in the dryer on high heat for 60 minutes to kill any remaining ticks. The oil of lemon, eucalyptus, and eugenol are sometimes employed as repellents, but their effectiveness against ticks is limited.

TICK REMOVAL

Avoiding ticks when outside may not be possible. Therefore, noticing a tick embedded in the skin requires immediate action. To remove a tick, disinfect the area with rubbing alcohol. Using pointed tweezers, grasp the tick by its head (as close to the skin’s surface as possible), and pull straight up. Don’t twist or jerk, which may break the tick, leaving part of its mouth in the skin. If this happens, remove the mouthparts with tweezers. The use of a magnifying glass may be helpful. Do not place hot matches, nail polish, or petroleum jelly on the tick to remove it. Clean the bite area again with rubbing alcohol or soap and water. Place the tick in a sealed container, plastic bag, or on tape to be brought to the physician’s appointment to help determine which tests are most appropriate. If individuals develop a fever or other symptoms within a couple of weeks of the tick bite, medical care should be sought immediately.

OTHER TICKBORNE DISEASES

While Lyme disease is the most common tickborne disease in the US, there are others of concern. Rocky Mountain spotted fever, Tidewater spotted fever, and other spotted fevers are also prevalent throughout the US. They are most often caused by the bacteria Rickettsia. The signs and symptoms are similar to those of Lyme disease, with the exception of the bull’s eye rash. Spotted fevers cause a petechial rash that covers much of the body, and sometimes an eschar (sloughing or dead tissue) appears at the site of the tick bite. Rickettsia also cause diseases, such as ehrlichiosis and anaplasmosis, which share signs and symptoms similar to spotted fevers. These bacterial diseases are treated similarly to Lyme disease.

The prevalence of human babesiosis, which is caused by microscopic protozoal parasites that infect red blood cells, is also growing, especially in New England. Babesiosis causes the same set of nonspecific symptoms, but can be life-threatening among immunocompromised populations. While tickborne viral diseases are endemic in much of the world, they have only recently started to emerge in the US, with a handful of cases of deer tick fever and Powassan virus being reported. Different drugs are needed to treat these protozoan and viral infections; thus, differential diagnosis is important to rule out these less common but potentially severe diseases.

CONCLUSION

Incidences of tickborne diseases are on a steady rise. While most frequently found in the Upper Midwest and Northeast states, Lyme disease cases have been reported in California and other parts of the West Coast. Tickborne diseases present a diagnostic quandary—cases that are diagnosed late are often more serious and challenging to treat. Lyme disease may have multifactorial presentations at various stages, and many people simply do not realize they have been bitten by a tick. The disease can masquerade as other disorders and is often misdiagnosed. Consequently, those who spend time outdoors in areas where ticks are prevalent need to take common-sense precautions. Individuals who know they have been bitten by a tick should seek immediate treatment. The good news is that when treated early, most people will fully recover.

No vaccine is available to protect against Lyme disease; prevention is the best method. As health care professionals, dental hygienists should remain up-to-date on tickborne diseases, so they can educate their patients and refer suspected cases as appropriate.

REFERENCES

- American Lyme Disease Foundation. Other Tickborne Diseases. Available at: aldf.com/majorTick.shtml. Accessed January 13, 2015.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tickborne Diseases of the US. Available at: cdc.gov/ticks/diseases. Accessed January 13, 2015.

- Parola P, Raoult D. Ticks and tickborne bacterial diseases in humans: an emerging infectious threat. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:897–928.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reported Cases of Lyme Disease by Year, United States, 1995–2013. Available at: cdc.gov/lyme/stats/chartstables/casesbyyear.html. Accessed January 13, 2015.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. How Many People get Lyme Disease? Available at: cdc.gov/lyme/stats/humanCases.html. Accessed January 13, 2015.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Lyme Disease Incidence Rates by State, 2004-2013. Available at: cdc.gov/lyme/stats/chartstables/incidencebystate.html. Accessed January 13, 2015.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Lyme Disease. Available at: cdc.gov/lyme. Accessed January 13, 2015.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Clinical Manifestations of Confirmed Lyme Disease Cases—United States, 2001–2010. Available at: cdc.gov/lyme/stats/chartstables/casesbysymptom.html. Accessed January 13, 2015.

- Harris R J. Lyme disease involving the temporomandibular joint. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1988;46:78–79.

- Steer AC, Malawista SE, Snydman DR, et al. An epidemic of oligoarticular arthritis in children and adults in three Connecticut communities. Arthritis Rheum. 1977;20:7.

- Bhate C, Schwartz RA. Lyme disease. Part I. Advances and perspectives. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:619–636.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Two Step Laboratory Testing Process. Available at: cdc.gov/lyme/diagnosistesting. Accessed January 13, 2015.

- Fix AD, Strickland GT, Grant J. Tick bites and Lyme disease in an endemic setting. JAMA. 1998;279:206–210.

- Bhate C, Schwartz RA. Lyme disease. Part II. Advances and perspectives. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:639–653.

- Wormser GP, Dattwyler RJ, Shapiro ED, et al. The clinical assessment, treatment, and prevention of Lyme disease, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and babesiosis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:1089–1134.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. February 2015;13(2):69–72.