Tackling the Vaccine Controversy

Oral health professionals who remain up-to date on immunization recommendations and disease etiology and pathogenesis will be well prepared to educate patients on this critical component of public health.

This course was published in the August 2015 issue and expires August 31, 2018. The author has no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Identify the main theories behind the anti-vaccination movement.

- Discuss the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s recommended vaccine schedule for adults.

- Describe the contagious diseases affecting adults and the immunizations that prevent them.

The discussion surrounding the safety of vaccines remains a hot topic. As prevention experts, dental hygienists are well positioned to provide patients and the general public with evidence-based information about immunizations and the role they play in improving global health. This article provides an overview of the opposition to vaccines, immunization recommendations, and disease etiology and pathogenesis so that oral health professionals are prepared to better educate patients.

Immunizations are one of the 20th century’s most cost-effective public health achievements.1 They have been proven to reduce the incidence and prevalence of some of the most deadly childhood diseases. Most children in the United States are fully vaccinated. For example, in 2013, 99.3% of all children in the US received the recommended vaccinations per the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) schedule.2 High rates of vaccination in a community ensure that most individuals are protected. This is called community immunity and it enables individuals who are ineligible to receive immunizations—such as infants, pregnant women, and the immunocompromised—to retain some protection because a widespread outbreak of contagious disease is unlikely.3 According to the CDC, vaccinations prevented 322 million illnesses, 21 million hospitalizations, and 732,000 deaths among children born between 1994 and 2013.2 Declining vaccination rates in some regions of the US, however, may reduce the strength of community immunity and contribute to the resurgence of serious illnesses.

OPPOSITION TO IMMUNIZATIONS

There are many reasons why some individuals oppose vaccination, with religious, philosophical, and safety objections remaining the most common. Religious objections to vaccines tend to be based on three premises: opposition to using human cells during the production of vaccines; belief that the human body should not be polluted with chemicals or animal byproducts; and faith that God is the ultimate healer.4

The philosophical reasons behind the anti-vaccination movement are varied. Some individuals mistrust Western medicine in general. Others believe vaccination is a violation of the individual’s right to make his or her own choices regarding health. Parents may oppose the government’s interference in making health care decisions for their children. Others believe that alternative treatments and natural immunity are superior to vaccination in fighting disease.5

Concerns regarding the safety of vaccinations are the most widely publicized reasons behind the anti-vaccination movement. In 1998, a paper was published in The Lancet that suggested an association between the measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine and autism, which spurred safety concerns. The paper was subsequently retracted in 2010 due to the author’s dishonesty and violation of research ethics. The paper’s author, Andrew Wakefield, MB, BS, FRCS, FRCPath, has since had his medical license revoked. Additional safety concerns were related to the use of the mercury-containing preservative thimerosal in many vaccines. Critics suggested that thimerosal caused autism, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, sudden infant death syndrome, and speech and language delays.6 Extensive research was conducted on the effects of thimerosal and no evidence of harmful effects was ever discovered. To quell public fears, however, thimerosal was removed from all vaccines administered to children age 6 and younger in 2001, with the exception of the influenza vaccine.6

DISEASE AND VACCINE DESCRIPTIONS

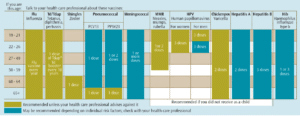

An extensive body of evidence supports the safety and efficacy of vaccinations, and their widespread use has meant that deadly childhood diseases including polio and smallpox have been virtually eliminated. Today, the CDC recommends 16 immunizations for children and 11 for adults to prevent a variety of infectious diseases. The following section describes the diseases that affect adults and the vaccines that prevent them. Table 1 lists the vaccinations recommended for adults by the CDC.

Diphtheria is an acute, communicable respiratory disease caused by toxigenic strains of the Gram-positive, aerobic, nonmotile, rod-shaped bacterium Corynebacterium diphtheria.7 The bacterium usually invade the mucous membranes of the nasal and respiratory passageways, which leads to breathing difficulties. In advanced stages, diphtheria can damage the heart, kidney, and nervous system, leading to paralysis or death.8

There are four combination vaccines used to prevent diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis: DTaP, DT, Tdap, and Td. DTaP and DT are given to children younger than 7, and Tdap and Td are given to children older than 7 and adults. The CDC recommends that health care professionals receive the Tdap and Td booster, especially if they are in close contact with children younger than 12 months.8 A booster is required every 10 years to preserve immunity.8

Tetanus is a noncommunicable disease caused by the Gram-positive anaerobic bacterium Clostridium tetani, which is usually found in soil, dust, or manure. It is transmitted by direct contact with an infected specimen. Tetanus presents as an acute, generalized increase in skeletal muscle rigidity. Once the organism’s toxin is absorbed into the bloodstream and the nervous system becomes affected, convulsive spasms will occur. Symptoms lead to complications such as laryngospasm, bone fracture, pulmonary embolism, aspiration pneumonia, respiratory depression, and death. Due to high vaccination rates, tetanus is uncommon in the US.9

Pertussis, or whooping cough is the only vaccine-preventable disease whose incidence is rising. This increase may be due to higher worldwide awareness of the disease, better diagnostic testing and reporting of the disease, increased circulation of the bacteria, and waning immunity.10 It is a highly contagious respiratory disease caused by the aerobic, Gram-negative bacteria Bordetella pertussis. The bacteria adhere to and inactivate the cilia that line the respiratory tract, preventing the cilia from performing their protective functions such as clearing secretions.10 Pertussis can lead to weight loss, incontinence, and rib fracture from prolonged and violent coughing.8

Haemophilus influenza type B (Hib) is caused by a bacterial infection with the Gram-negative, nonmotile bacteria Haemophilus influenzae.11 Children younger than 5 and medically compromised adults are most susceptible.12 Hib can cause bacteremia; pneumonia and edema in the throat, which can impede breathing; and death.11 Before universal vaccination in the US, Hib was the leading cause of bacterial meningitis among children younger than 5.12 Since the inception of the vaccine, the number of Hib cases has decreased 99%.12

Hepatitis A is caused by a nonenveloped, positive-stranded RNA hepatitis A virus within the picornavirus family. It is largely transmitted by a direct oral-fecal route but can also be transmitted parenterally.13 Hepatitis A causes flu-like symptoms, jaundice, diarrhea, and stomach cramping.14 One in five individuals with hepatitis A will need hospitalization, and many adults miss as much as 1 month of work during recovery.14

Hepatitis B is caused by an enveloped, double-stranded DNA hepatitis B virus (HBV) that attacks the liver and can cause lifelong infection, cirrhosis, or cancer.13,14 Among HBV-infected children, 25% will die of liver complications.13 In 2009, there were 38,000 new reported cases and 2,000 to 4,000 deaths due to hepatitis B.14 The virus is transmitted by direct contact. The CDC recommends vaccination for individuals who come into contact with human blood. Since the inception of the hepatitis B vaccine in 1990, new infections among children and adolescents have decreased 95%.14

Shingles is caused by an exclusive human neurotropic alpha-herpesvirus varicella zoster. The primary infection with varicella causes chickenpox and varicella exposure in infancy predisposes individuals to shingles later in life.14 Shingles usually begins with a prodromal phase characterized by pain, itching, numbness, tingling, unpleasant sensations, or sensitivity to touch.15 A few days later, a unilateral maculopapular rash appears at the site of cranial nerve involvement. One in five people experience sustained, severe pain, even after the vesicles have healed. The CDC recommends the shingles vaccine for everyone older than 60. The vaccine decreases the risk of outbreak by 50%.16

Papillomaviruses are heterogeneous, small, icosahedral, nonsegmented, nonenveloped double-stranded DNA genomes. Human papillomavirus (HPV) is a contributing risk factor for many human diseases. Three vaccines target particular strains of HPV that cause genital warts and oral and cervical cancer. HPV 16 and 18 are found in 96% of cervical cancer cases and 63% of oropharyngeal cancers.17 The CDC recommends HPV?vaccination for boys and girls age 11 and older.18

Influenza is caused by varying strains of the influenza virus transmitted by droplet aerosols. Symptoms include fever, cough, sore throat, rhinitis, headaches, lethargy, and gastrointestinal upset. Influenza vaccination is considered the most effective strategy for prevention.19 In 2013-2014, less than half of the US population received the influenza vaccine. During the 2013-2014 flu season, 109 children died due to influenza and 90% of influenza-related deaths occurred in individuals older than 65.20 The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommends annual influenza vaccination for all individuals older than 6 months.20

The measles virus is an enveloped, helical, single-stranded RNA virus. It is a highly contagious, acute viral illness and is transmitted via droplet aerosol or by direct contact. One of the early warning signs is the appearance of tiny white lesions intraorally. Measles, also called rubeola, causes high fever, skin rash, conjunctivitis, respiratory difficulties, ear infections, and, in rare cases, brain damage.21 Unvaccinated children are at highest risk for this serious disease.21,22 A measles outbreak began in January 2015—originating at Disneyland Park in Anaheim, California—and lasted until April 2015. The outbreak spread to 159 cases across 18 states and the District of Columbia.23 No deaths occurred, but 14% of those infected had to be hospitalized due to complications. Of those affected, 80% were unvaccinated.23

Mumps is a highly contagious disease transmitted by respiratory nasal droplets. Typical symptoms include fever, headache, muscle aches, lethargy, or swollen and tender parotid salivary glands.22,24 Less common complications include loss of hearing and voice, arthritis, mastitis, aseptic meningitis, pancreatitis inflammation of the brain and spinal column, or inflammation of male and female reproductive organs.24

Rubella is an infection caused by a spherical, single-stranded, enveloped RNA virus. It is transmitted through droplet aerosol or direct contact. Signs and symptoms include rash, lymphadenopathy of the head and neck, and a low-grade fever lasting about 3 days. Congenital rubella syndrome causes severe birth defects such as hearing impairment, ocular defects, growth retardation, intellectual disability, meningocephalitis, microcephaly, or heart and brain damage. When a woman is infected with the rubella virus early in pregnancy, she has a high likelihood of passing the virus to her baby, which may cause fetal or neonatal death.25

Meningitis is caused by multiple bacterial strains. Infants, college-age adults living in residence halls, and military personnel are at highest risk. The earliest signs and symptoms are a sudden onset of fever, headache, and a stiff neck. If infection occurs in the lining of the brain and spinal column, brain damage and deafness can occur. Meningitis is prevented by vaccination with Hib, pneumococcus, and meningococcus.26

Pneumonia is an infection of the lungs that affects all age groups. Infants, young children, older adults, and those with weakened immune or respiratory systems are at greatest risk.26 Pneumonia can be caused by several agents such as bacteria, viruses, and fungi.27 Streptococcus pneumonia is the most common cause of pneumonia and is sometimes referred to as pneumococcus.28 In the US, several vaccines can prevent infection by bacteria or viruses that may cause pneumonia, such as pneumococcal, Hib, pertussis, varicella, measles, and influenza.27

Varicella zoster virus causes chickenpox and can lead to shingles later on. It is highly contagious, and transmission occurs by direct contact or through respiratory aerosols.15 Prior to widespread vaccination, 4 million individuals in the US came down with the chickenpox each year, leading to annual death rate 100 to 150.29 Chickenpox is typically seen in children age 1 to 9.15 Primary infection in adults is usually more severe and may be accompanied by interstitial pneumonia. Signs and symptoms include fever, headache, loss of appetite, and concurrent rash on the skin and mucosa. The rash begins as tiny macules and rapidly progresses to papules, followed by a vesicular stage and crusting of lesions.15

CONCLUSION

Providing patients with evidence-based information on the safety and efficacy of vaccines is key to helping them make informed decisions. By understanding the etiology and pathogenesis of these diseases, health care providers can support efforts to improve public health, as well as protect their own health by keeping up-to-date on vaccinations.

REFERENCES

- National Conference of State Legislatures. Immunizations policy issues overview. 2015, January. Available at: ncsl.org/research/health/immunizations-policy-issues-overview.aspx. Accessed July 20, 2015.

- Elam-Evans L, Yankey D, Singleton J, Kolasa M, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among children aged 19-35 months—United States, 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:741–748.

- United States Department of Health and Human Services. Community Immunity. Available at: vaccines.gov/basics/protection. Accessed July 20, 2015.

- College of Physicians of Philadelphia. Cultural Perspectives on Vaccination. Available at: historyofvaccines.org/content/articles/cultural-perspectives-vaccination. Accessed July 20, 2015.

- Salmon DA, Omar SB. Individual freedoms versus collective responsibility: Immunization decision making in the face of occasionally repeating values. Emerging Themes in Epidemiology. 2006;3:1-3.

- College of Physicians of Philadelphia. History of Anti-Vaccination Movements. Available at: historyofvaccines.org/content/articles/history-anti-vaccination-movements. Accessed July 20, 2015.

- Hardy RB, Dittmann S, Sutter R. Current situation and control strategies for resurgence of diphtheria in newly independent states. Lancet. 1996;347:1739–1750.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vaccine Information Statements: Diphtheria, Tetanus, and Pertussis. Available at: cdc.gov/ vaccines/hcp/vis/vis-statements/dtap.html. Accessed July 20, 2015.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About Tetanus. Available at: cdc.gov/tetanus/about/index. html. Accessed July 20, 2015.

- Rivard G, Vierra A. Staying ahead of pertussis. Journal of Family Practice. 2014;63(11):658–669.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Haemophilus influenzae Disease (Including Hib): Causes and Transmission. Available at: cdc.gov/hi-disease/about/causes-transmission.html. Accessed July 20, 2015.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vaccine Information Statements: Haemophilus Influenzae Type b (Hib) VIS. Available at: cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/vis/vis-statements/hib.html. Accessed July 20, 2015.

- Stene-Johansen K, Skaug K, Blystad H, Grincle B. A unique hepatitis A virus strain caused an epidemic in Norway associated with intravenous drug abuse. Scand J Infect Dis. 1998;30:35–28.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vaccine Information Statements: Hepatitis B VIS. Available at: cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/vis/vis-statements/hep-b.html. Accessed July 20, 2015.

- Mueller N, Gilden D, Cohrs R, Mahalingam R, Nagel M. Varicella zoster virus infection: Clinical features, molecular pathogenesis of disease, and latency. Neurol Clin. 2008;26:675–678.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vaccine Information Statements: Shingles VIS. Available at: cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/vis/vis-statements/shingles.html. Accessed July 20, 2015.

- Cleveland J, Junger M, Saraiya M, Markowitz L, Dunne E, Epstein J. The connection between human papillomavirus and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas in the United States. Implications for Dentistry. J Am Dent Assoc. 2011;142:915–924.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vaccine Information Statements: HPV (Human Papillomavirus) Gardasil® VIS. Available at: cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/vis/vis-statements/hpv-gardasil.html. Accessed July 20, 2015.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vaccine Information Statements: Inactivate Influenza VIS. Available at: cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/vis/vis-statements/flu.html. Accessed July 20, 2015.

- Reed C, Kim IK, Singleton JA, et al. Estimated influenza illnesses and hospitalizations averted by vaccinations—United States 2013-14 influenza season. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:1151–1154.

- Yanagi Y, Takeda M, Ohno S. Measles virus: cellular receptors, tropism, and pathogenesis. J Gen Virol. 2006;87:2767–2779.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vaccine Information Statements: MMR (Measles, Mumps, and Rubella) VIS. Available at: cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/vis/vis-statements/mmr.html. Accessed July 20, 2015.

- Clemmons N, Gastanaduy P, Fiebelkorn AP, Redd S, Wallace GS. Measles—United States, January 4–April 2, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;64:373–376.

- Shah A, Smolensky M, Burau K, Cech I, Loi D. Seasonality of primarily childhood and young adult infectious diseases in the United States. Chronobiology Int. 2006;23:1065–1082.

- Olajide OM, Aminu M, Randawa AJ. Seroprevalance of rubella-specific IgM and IgG antibodies among pregnancy women seen in a tertiary hospital in Nigeria. Int J Womens Health. 2015;7:75–83.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Bacterial Meningitis. Available at: cdc.gov/meningitis/ bacterial.html. Accessed July 20, 2015.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pneumonia. Available at: cdc.gov/pneumonia/ index.html. Accessed July 20, 2015.

- National Health System of the United Kingdom. Pneumonia—Causes. Available at: nhs.uk/ Conditions/Pneumonia/Pages/Causes.aspx. Accessed July 20, 2015.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vaccine Information Statements: Chickenpox VIS. Available at: cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/vis/vis-statements/varicella.html. Accessed July 20, 2015.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. August 2015;13(8):18,21–23.