EDWARDOLIVE / ISTOCK / GETTY IMAGES PLUS

EDWARDOLIVE / ISTOCK / GETTY IMAGES PLUS

Support Oral Health in Patients With Removable Dental Prostheses

Removable oral prosthesis hygiene and care require approaches that incorporate insight from patients, multidisciplinary healthcare teams, and researchers.

This course was published in the August 2022 issue and expires August 2025. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Discuss how care of removable dental prostheses impacts health.

- Describe the essential information that patients should receive with regards to caring for their prosthesis.

- Identify the role of dental hygienists, nurses, dietitians, and pharmacists in improving outcomes for patients using removable dental prostheses.

Severe tooth loss (having ≤ 8 natural teeth) and edentulism negatively impact health and quality of life.1,2 In 2019, the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported one in six (17%) adults over the age of 65 and 43% of current smokers had lost all their teeth.2 In 2020, approximately 41 million Americans reported using partial or full dentures which, as the population ages, is projected to increase to approximately 42.5 million by 2024.3 Removable dental prostheses can impact patient health, quality of life, nutrition, and social and professional interactions. Psychologically, denture wearers experience notable anxiety around oral care including a sense of inferiority provoked by tooth loss and denture use that can impact day-to-day functioning.4,5 While proper fit, care, and maintenance of dentures are vital to overall health and well-being, this may not be widely achieved.4,6–8

Ill-fitting dentures can cause chronic mucosal irritation and trauma, increasing the risk of ulcerated lesions and oral cancer. Ulcers may be subsequently vulnerable to infection.9–11 For example, while Candida is common in the oral mucosa, its accumulation can lead to candidiasis and drive further inflammation and disease sequelae in susceptible individuals.6,11 Both oral trauma and poor denture hygiene have been implicated in the development of denture-induced stomatitis (DIS), a frequent occurrence among denture wearers. Evidence of oral fungal infection is detected in 70% of individuals showing clinical signs of DIS.12,13 Proper care and maintenance of dental prostheses are key to favorable outcomes.

Removable oral prosthesis hygiene and care require greater attention, including approaches that incorporate insight from patients, multidisciplinary healthcare teams, and researchers. This paper will describe unmet needs in removable dental prosthesis care and the integral role of dental hygienists and other healthcare team members in improving outcomes for patients who use removable prostheses.

Evidence Gap Surrounding Denture Care

Denture care is an integral component of overall health and well-being. Achieving optimal outcomes depends on solid evidence that informs clinical practice and reinforces patient compliance.

At the foundation of unmet needs is a lack of systematic research evaluating the relative impact of different hygiene measures on oral health, and upon adverse health outcomes. A Cochrane systematic review on different denture cleaning interventions in adults found only six randomized controlled trials suitable for analysis of complete dentures (none in partial); however, definitive conclusions could not be made due to the heterogeneity of the study participants and the methods used in the studies.14 The review mentioned isolated reports that have found chemical cleaning and brushing to be more effective than placebo in reducing denture plaque and microbial count. While studies examining various methods in different patient populations have been reported, the lack of a systematic approach precludes evidence-based clinical treatment recommendations.

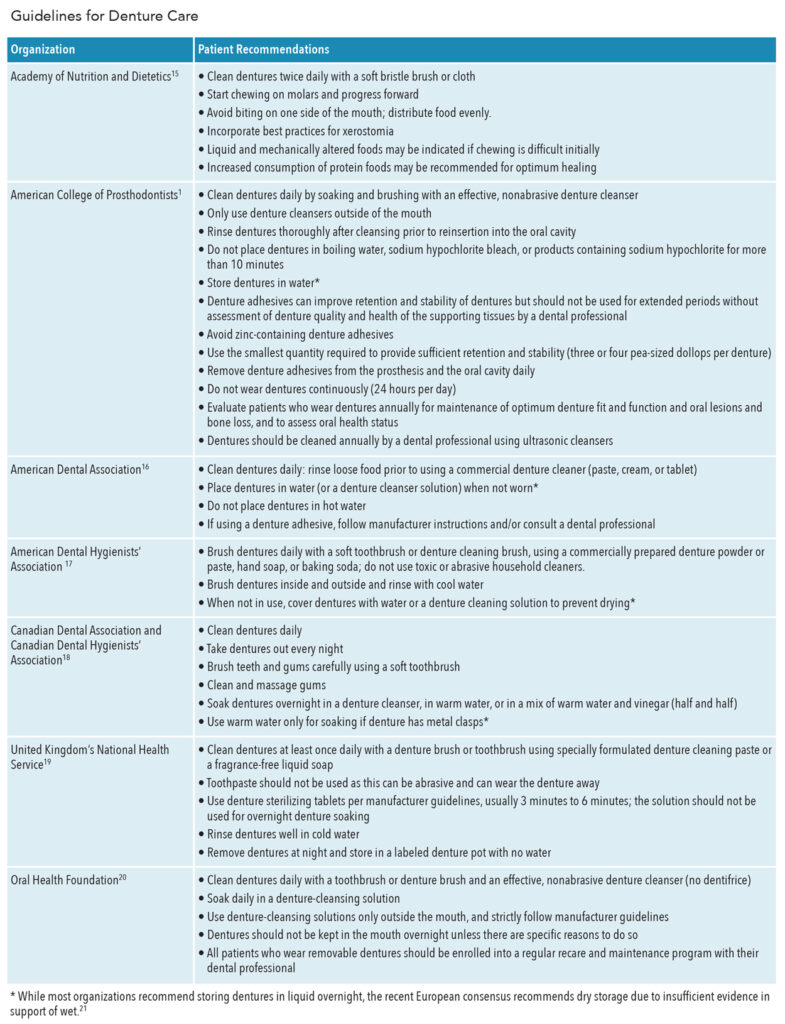

An extension of the evidence gap is the ambiguity surrounding clinical practice recommendations. There is no established consensus regarding oral hygiene measures and very few national or international guidelines on appropriate denture cleaning.1,5,15–20 Existing recommendations vary across countries and specialties, creating a possible disconnect between healthcare providers, and contributing to patient confusion. These issues are further exacerbated by online resources that can be vague or incorrect.5 For example, regarding overnight storage of dentures, while the American College of Prosthodontists advises storing in water to prevent drying, the National Health Service in the United Kingdom advises storing them dry, and other organizations avoid making any recommendation.21 Consequently, many patients lack the necessary knowledge on how to best care for their oral prosthesis.5,8,22

This knowledge gap is compounded by practitioner time constraints and a lack of clarity around who should impart the available information. Patients engage with a dentist when acquiring new prostheses but detailed instruction regarding the care for the prosthesis and the impact of the prosthesis on eating habits and oral and general health may not be covered. A positive relationship between combined verbal and written instruction and denture cleanliness has been demonstrated.8 Long-term follow-up and surveillance of care also need improvement, particularly in residents of long-term facilities and those with special needs. Ideally, cohesive education should be delivered by a multidisciplinary care team wherein dental hygienists, nurses, pharmacists, and dietitians collaborate to reinforce the core principles of dental prosthesis hygiene.

Comprehensive training of healthcare providers from undergraduate to post-graduate level and through continuing education in removable prosthesis care is vital.21 Thus, allied health professionals may need to evaluate whether other healthcare providers are given adequate training, beginning with the educational curriculum. For example, curricula should:

- Undergo evaluation to ensure that caring for oral prostheses and the negative consequences of insufficient care are adequately emphasized

- Include the value of multidisciplinary approaches to convey knowledge to patients, including the roles of dental hygienists, nurses, dietitians, and pharmacists

- Receive periodic updates in tandem with emerging data, revised clinical recommendations, and changing health behaviors

The impact of socioeconomic status on denture use, care, and adverse outcomes cannot be overstated. Patients of low socioeconomic status are more likely to need a removable prosthesis, are disproportionally affected by oral diseases, and are less likely to have access to dental care.23–25 Social, economic, and cultural issues should be incorporated into curricula and healthcare approaches, with educational materials tailored to meet the unique needs of these patients. Research evaluating the extent to which existing curricula meet these needs would provide an important scaffold for developing recommendations to improve outcomes in underserved communities.

Role of the Dental Hygienist

As licensed professionals trained in the prevention of oral diseases, dental hygienists are well-positioned to provide patients with the education required to care for their prostheses and to monitor patient progress, identifying problems as they arise. They are in contact with patients, accessible, trained in oral health, and can liaise between the patient and dentist should clinical intervention be required. Dental hygienists and other practitioners can significantly impact outcomes by asking questions to gauge patients’ existing knowledge and hygiene practices. Simple questions can provide important insights that may guide further intervention, including:

- Do your dentures fit well?

- Are you experiencing any gum tenderness or irritation?

- Do you have any preference for denture care products?

- Are you having difficulty inserting or removing your prosthesis?

- Are you experiencing any other health issues or discomfort?

During patient encounters, symptoms—such as oral malodor, mouth ulcers, red or swollen gingiva, scaling and shallow painful fissures at the corners of the mouth, dry mouth and lips, coated tongue, broken teeth, and/or thick secretions—should prompt further inquiry into the educational needs of the patient.26 With an established knowledge base and care competence, dental hygienists can educate patients on best practices for maintaining oral prostheses, prioritizing areas of greatest need, and encouraging regular examinations. More frequent evaluations may be needed in certain high-risk populations such as those with Parkinson disease, neurocognitive disorders, physical handicaps, dysphagia, and immunodeficiency.21

Prior to the appointment for placement of a new denture, dental hygienists can counsel individuals about what to expect and recommend soft and easy-to-chew foods as they adapt to the new prosthesis. Encourage chewing longer and eating slower as swallowing may be more challenging. During the adaptation period, fibrous food should be cut into small pieces and individuals should begin by chewing with their molars and progress to biting with incisors when they feel more comfortable with the prosthesis. Initially, diet may be limited due to residual inflammation; liquid nutritional supplements may be required for the first week or two to facilitate calorie intake and promote tissue repair. At follow-up visits, dental hygienists can inquire about dietary habits, note changes in food preferences indicative of deterioration in denture fit, and consider vitamin D insufficiency which may play a role in periodontal health.27 Dairy products fortified with vitamin D should be encouraged to slow the rate of bone loss. A consultation with a dietitian may be warranted if the patient reports unexpected weight loss, which may be due to changes in eating patterns or avoidance of certain food groups.15,28 Additional proactive measures include promoting an overall healthy diet, limiting sweet foods to mealtimes to reduce denture exposure to an acidic environment, and encouraging consumption of anticariogenic foods that stimulate salivary flow.

Nurses, pharmacists, and dietitians can work in parallel with dental hygienists to bolster education. Oral health has been shown to deteriorate during hospitalizations and in long-term care facilities.26 Nurses working in these settings may take a similar approach to dental hygienists in assessing and intervening. Issues resulting from poor oral care should be treated as a high priority and task competence should be assessed to determine the need for regular assistance with brushing and other oral care procedures. Pharmacists can also engage with patients regarding the impact of medications on oral health, advise on denture care and other oral care products and their correct usage, and encourage continuity of care.29

Best Practices

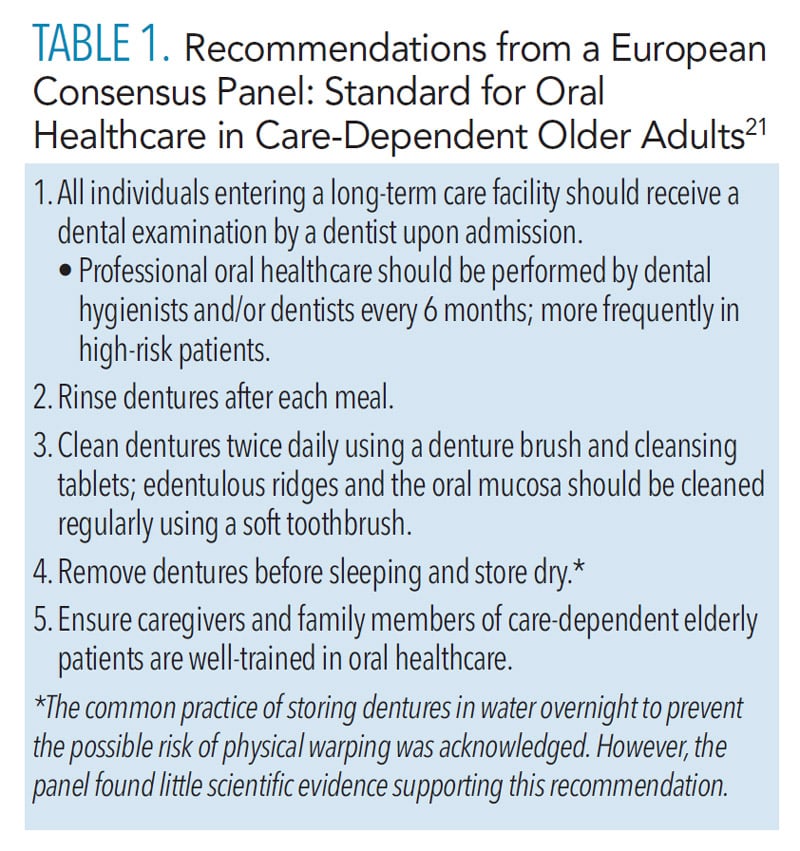

Effective communication of best practices regarding oral prosthesis hygiene would greatly improve oral health. Several professional societies have issued denture care statements that agree on general principles, but they lack cohesion and specificity regarding best practices for oral prosthesis care. Recently, a panel of 31 interdisciplinary experts composed of dentists, dental hygienists, and physicians from 17 European countries evaluated oral health policy, access to dental care, oral hygiene measures, and training levels and published a European consensus statement on minimum standards for oral hygiene in care-dependent older adults (Table 1).21 The panel further concurred that insufficient attention is given to this important topic and concluded that the proper training of the dental professional is paramount to successful outcomes.21

The shape of the oral cavity changes over time, impacting the fit of oral prostheses, and illustrating the utility of regular oral examination and fit assessments. The dynamic nature of the oral cavity and the needed adjustments should be emphasized during patient interactions. Where possible, enrollment in a regular continuing care program should be encouraged.20

Improving Outcomes

Implementing education initiatives can significantly improve knowledge, attitudes, performance, and outcomes.30 While a detailed description of the approaches that could improve healthcare provider education is beyond the scope of this review, key concepts could include unbiased evaluation of existing frameworks; ensuring a patient-centric, multidisciplinary team-based oral healthcare; and understanding how multiple disciplines could interact to provide the most effective and efficient healthcare outcomes.

The development of an evidence-based consensus statement from dental hygienists, nurses, registered dietitians, and pharmacists on a standard for oral prosthesis care, maintenance, and storage would be an important clinical practice guide. Engaging advocacy groups in the development of guidelines helps to maximize commitment among relevant professional communities. Development and implementation of social determinants of health framework would also be a valuable addition to existing curricula.

In parallel, systematic research is required to clarify the role and value of different practices and strengthen the educational framework. This could include: defining the level of “cleanliness” needed to prevent oral disease; systematically comparing the efficacy of mechanical and chemical methods of oral prosthesis cleaning; elucidating the relationships between denture care, oral health, and disease; exploring the impact of denture adhesives and different methods of adhesive removal on oral tissue; costs-effectiveness of various recommendations; and longitudinal analyses of the psychosocial and behavioral factors that contribute to oral health inequalities.1,14,20,24

Conclusions

Inadequate care of oral prostheses contributes to morbidity and creates an avoidable burden on healthcare systems. Dental hygienists, nurses, dietitians, and pharmacists play an important role in the education of patients. While many are well-versed in the proper care of removable dental prostheses, by improving educational curricula and training of healthcare providers, a rounded multidisciplinary approach to oral health and dental prosthesis care can be achieved. Ultimately, a concerted effort by professional societies, policymakers, and payers will be needed to close the existing gaps in education and care delivery, particularly to at-risk and underserved patient populations.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Ellen R. Guritzky, MSJ, RDH; Meri Pozo, PhD, CMPP; and Caitlin McOmish for their assistance with this manuscript.

Bonus Web Content

References

- Felton D, Cooper L, Duqum I, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for the care and maintenance of complete dentures: a publication of the American College of Prosthodontists. J Prosthodont. 2011;20 Suppl 1:S1–S12.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Oral Health Surveillance Report: Trends in Dental Caries and Sealants, Tooth Retention, and Edentulism, United States, 1999–2004 to 2011–2016. Available at: cdc.gov/oralhealth/publications/OHSR-2019-index.html. Accessed July 6, 2022.

- Statista. US Population: Usage of Dentures from 2012 to 2024. Available at: statista.com/statistics/㕶/usage-of-dentures-in-the-us-trend/. Accessed July 6, 2022.

- Shaha M, Varghese R, Atassi M. Understanding the impact of removable partial dentures on patients’ lives and their attitudes to oral care. Br Dent J. May 27, 2021. Epub.

- Axe AS, Varghese R, Bosma M, Kitson N, Bradshaw DJ. Dental health professional recommendation and consumer habits in denture cleansing. J Prosthet Dent. 2016;115:183–188.

- Kanli A, Demirel F, Sezgin Y. Oral candidosis, denture cleanliness and hygiene habits in an elderly population. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2005;17(6):502-507.

- Dikbas I, Koksal T, Calikkocaoglu S. Investigation of the cleanliness of dentures in a university hospital. Int J Prosthodont. 2006;19:294–298.

- Milward P, Katechia D, Morgan MZ. Knowledge of removable partial denture wearers on denture hygiene. Br Dent J. 2013;215:E20.

- Singhvi HR, Malik A, Chaturvedi P. The role of chronic mucosal trauma in oral cancer: a review of literature. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol. 2017;38:44-50.

- Manoharan S, Nagaraja V, Eslick GD. Ill-fitting dentures and oral cancer: a meta-analysis. Oral Oncol. 2014;50:1058–1061.

- Frazer CA, Frazer RQ, Byron RJ. Prevent infections with good denture care. Nursing. 2009;39:50–53.

- Sadig W. The denture hygiene, denture stomatitis and role of dental hygienist. Int J Dent Hyg. 2010;8:227–231.

- Shulman JD, Rivera-Hidalgo F, Beach MM. Risk factors associated with denture stomatitis in the United States. J Oral Pathol Med. 2005;34:340–346.

- de Souza R, de Freitas Oliveira Paranhos H, Lovato da Silva CH, Abu-Naba’a L, Fedorowicz Z, Gurgan CA. Interventions for cleaning dentures in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;4:CD007395.

- Mallonee LFH, Boyd LD, Stegeman C. Oral health and nutrition practice paper of the academy of nutrition and dietetics. J Acad of Nutr Diet. 2014;114:958–970.

- American Dental Association. Denture Care and Maintenance. Available at: ada.org/resources/research/science-and-research-institute/oral-health-topics/dentures. Accessed July 6, 2022.

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association. Senior Oral Health. Available at: adha.org/sites/default/files/쨇_Senior_Oral_Health_䁮.pdf. Accessed July 6, 2022.

- Canadian Dental Association. Denture care. Available at: cda-adc.ca/en/oral_health/cfyt/dental_care_seniors/dental_care.asp. Accessed July 6, 2022.

- National Health Service, Health Education England. Mouth Care Matters: A Guide for Hospital Healthcare Professionals. Available at: mouthcarematters.hee.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/䁴/떔/葍/MCM-GUIDE-2019-Final.pdf. Accessed July 6, 2022.20.

- Bartlett DCN, de Baat C, Duyck J, Goffin G, Muller F, Kawai Y. White paper on optimal care and maintenance of full dentures for oral and general health. Available at: dentalhealth.org/Handlers/Download.ashx?IDMF=8a8a723a-20c5-4064-8f37-1947ab94481a. Accessed July 6, 2022.

- Charadram N, Maniewicz S, Maggi S, et al. Development of a European consensus from dentists, dental hygienists and physicians on a standard for oral health care in care-dependent older people: an e-Delphi working group. Gerodontology. 2021;38:41–56.

- Peracini A, Andrade IM, Paranhos Hde F, Silva CH, de Souza RF. Behaviors and hygiene habits of complete denture wearers. Braz Dent J. 2010;21:247–252.

- Palmqvist S, Söderfelt B, Vigilt M, Kihl J. Dental conditions in middle-aged and older people in Denmark and Sweden: a comparative study of influence of socioeconomic and attitudinal factors. Acta Odontol Scand. 2000;58:113–118.

- International Centre for Oral Health Inequalities Research & Policy. Social Inequalities in Oral Health: From Evidence to Action. Available at: media.news.health.ufl.edu/misc/cod-oralhealth/docs/posts_frontpage/SocialInequalities.pdf. Accessed July 6, 2022.

- Northridge ME, Kumar A, Kaur R. Disparities in access to oral health care. Annu Rev Public Health. 2020;41:513–535.

- Otukoya RSE. Principles of effective oral and denture care in adults. Nursing Times. 2018;114(11):22–24.

- Botelho J, Machado V, Proença L, Delgado AS, Mendes JJ. Vitamin D deficiency and oral health: a comprehensive review. Nutrients. 2020;12:1471–1487.

- Dietitians Association of Australia. Joint Position Statement on Oral Health and Nutrition. Available at: dietitiansaustralia.org.au/wp-content/uploads/떐/葑/DAA-DHSV-Joint-Statement-Oral-Health-and-Nutrition.pdf. Accessed July 6, 2022.

- Krinsky D. Prevention of hygiene-related oral disorders. Pharmacy Today. 2021;27:17.

- Frenkel H, Harvey I, Newcombe RG. Improving oral health in institutionalised elderly people by educating caregivers: a randomised controlled trial. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2001;29:289–297.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. August 2022; 20(8)42-45.