DR_MICROBE / ISTOCK / GETTY IMAGES PLUS

DR_MICROBE / ISTOCK / GETTY IMAGES PLUS

Cancer and the Oral Systemic Link

Healthcare professionals play a vital role in the prevention of oral and systemic disease.

This course was published in the August 2022 issue and expires August 2025. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Discuss the prevalence and risks associated with cancer and periodontal diseases.

- Identify the association between oral bacteria and colon, gastric, and oropharyngeal cancers.

- List additional factors that impact oral health and cancer risk.

- Explain the innovative methods that may help patients improve and maintain their oral health.

Oral health is essential to overall health, and systemic diseases and their treatment often cause significant oral manifestations. Conversely, oral infections may raise the risk of morbidities, including cancer.1 A correlation between periodontal diseases and various cancers has been found, and research is ongoing. A meta-analysis showed a statistically significant association between periodontal diseases and all cancers, both combined and individually.2 The cancers studied included gastrointestinal, pancreatic, prostate, breast, corpus uteri, lung, hematological, esophageal/oropharyngeal, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma.3 Through interprofessional collaboration, healthcare professionals can play a vital role in the prevention of oral and systemic disease by identifying early signs and symptoms, which may improve the overall health of their patients.

Cancer Risk and The Oral Systemic Link

In the United States, cancer is the second leading cause of mortality, behind only heart disease.2 Cancer results in more than 10 million deaths per year across the globe.2 Considered some of the deadliest diseases, cancers of the colon, gastrointestinal system, and oropharynx often result in mortality.4–6

Many mutualistic oral microorganisms are associated with various cancers due to the translocation of bacteria. In some cases, the initiation of the tumor process is not due to activities of a specific organism but rather because of instability in the composition of the bacterial communities, or dysbiosis. This is frequently associated with increased inflammatory responses found in conditions such as periodontal diseases.3

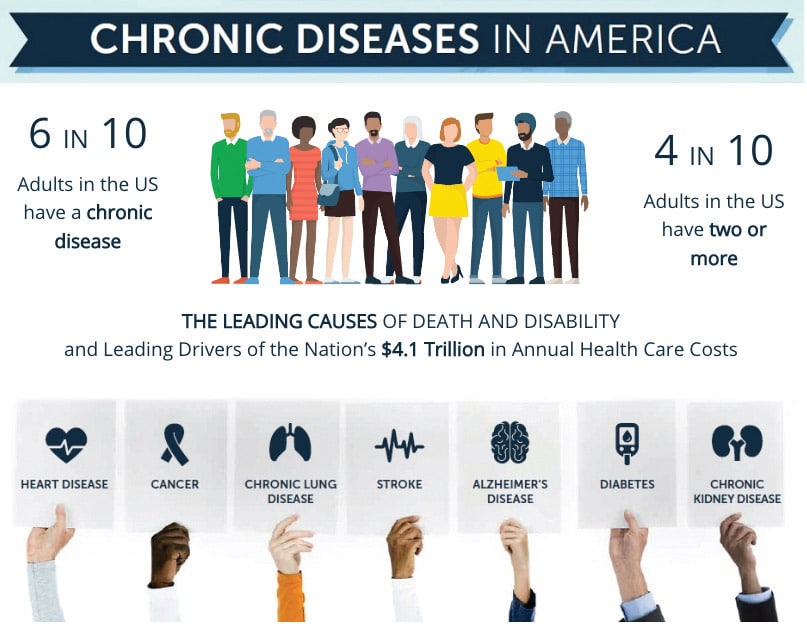

Six in 10 Americans have a chronic disease (Figure 1), and this number is only expected to increase.7 As such, oral health professionals will need to be knowledgeable on how the oral cavity is linked to systemic diseases and cancers. A 2019 survey found that two-thirds of patients with severe periodontitis were unaware of the correlation to systemic disease or the benefits of treating the disease with periodontal therapy.8

Periodontal Diseases

Periodontal diseases are the most common chronic inflammatory conditions.5 Periodontal diseases are very common among adults between the ages of 45 and 64, with one in 10 experiencing severe periodontitis.1 Although a plethora of periodontal pathogens play a significant role in the development of periodontal diseases, Fusobacterium nucleatum is a major contributor. This Gram-negative bacterium is critical in bacterial biofilm formation.5 The bacterial biofilm adheres to the teeth, causing a chronic bacterial infection that is destructive to the gingiva and supporting bone. F. nucleatum produces serine proteases that can destroy the extracellular matrix proteins, fibrinogen, fibronectin, and type I and IV collagen.5,9 The resultant inflammatory response causes alveolar bone destruction and loss of tissue attachment creating periodontal pockets.10

Bacteria can be transmitted throughout the body through many routes, one of which is the swallowing of oral bacteria. Swallowed saliva, ingested food, and fluids spread the microbiota of the oral cavity, providing a passage to the gastrointestinal tract. Another route of bacterial transmission is through the bloodstream and systemic circulation to joints, heart, and colon. Oral microbiota can directly access the bloodstream during toothbrushing, tooth extraction, or mastication. Gram-negative microorganisms—such as F. nucleatum, Porphyromonas gingivalis, and other bacteria—are able to invade the bloodstream through ulcerated gingival pockets.4

Periodontal diseases can significantly increase inflammatory markers and molecules that affect the inflammatory response. The inflammatory response promotes the release of reactive oxygen species and other metabolites that, in turn, support cancer initiation.11 Recent studies show that periodontal diseases may be linked to colon and gastric cancer due to the abundance of similar bacteria in these areas.4,9 The presence of F. nucleatum produces interleukin-8, which increases local inflammation.10 Consequently, T-cell responses are suppressed, and peripheral white blood cells die. Innate antimicrobial peptides and human B defensins within gingival epithelial cells increase, thereby, suppressing the growth of other competitors.10 Periodontal diseases are a risk factor for cancer due to the long-standing chronic inflammatory status of the periodontal tissues.11

Colon Cancer

Colon cancer is the third most common cancer in the US and is the fourth leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide.4 The term colorectal cancer refers to a slowly developing cancer that begins as a tumor or tissue growth on the inner lining of the rectum or colon. If this abnormal growth, known as a polyp, becomes cancerous, it can form a tumor on the wall of the rectum or colon. Subsequently, the condition can spread into lymph or blood vessels, which in turn, increases the chance of metastasis to other anatomical sites.9 Studies show that many bacterial members associated with the oral microbiota appear in gastrointestinal tumors, especially those associated with colorectal cancer.4 Research by Nakatsu et al12 found high numbers of oral bacteria, including Fusobacterium, Gemella, Peptostreptococcus, and Parvimonas, among patients with colon cancer.

Gastric Cancer

Gastric cancer is the fifth most common cancer worldwide. More than 1 million new cases are diagnosed each year, and approximately 783,000 people will die from the disease each year.5 The anatomical regions for gastric adenocarcinomas are classified as cardia or noncardia, also known as distal stomach cancer. Cardia gastric cancers are related to obesity or gastroesophageal reflux disease. Distal stomach cancers are most common cause of chronic gastritis and inflammation of the gastric mucosa. Environmental factors such as dietary habits and low socioeconomic status increase stomach cancer risk. Gastrointestinal tumors are frequently malignant with high morbidity and mortality, and low early diagnosis rates.5

Gastric microbiota have a high number of bacteria translocation. Bacterial species associated with oral conditions, such as caries and periodontitis, including Fusobacteria, Porphyromonas, Prevotella, Klebsiella, Neisseria, Rothia, Veillonella, and Streptococcus, are also linked with the gastric microbiome. High levels of F. nucleatum, Clostridium colicanis, and Lactobacillus are contributing factors for gastric cancer.5

Oropharyngeal Cancer

Approximately 690,000 new cases of cancers of the lip, oral cavity, pharynx, or larynx are reported worldwide, making head and neck cancer (HNC) the sixth most common cancer in the world.6 Men are 3.5 times more likely to develop oropharyngeal cancer than women.1 Infection with the human papillomavirus (HPV) is associated with oropharyngeal cancer. A strong relationship also exists between periodontitis and oropharyngeal cancer among HPV-positive individuals. Research shows that chronic generalized periodontitis is predominant in approximately 80% of patients with oral and/or oropharyngeal cancer.13

Oral dysbiosis is a frequent event in oral and oropharyngeal carcinogenesis. Using an oral rinse as a platform for oral microbiome characterization, Lim et al14 found that the oral microbiome was capable of noting oral cavity cancer and oropharyngeal cancers with 100% and 90% sensitivity and specificity, respectively. These findings concurred with previous findings, that the differences in microbial abundance and diversity may have a role in cancer initiation and progression.

Impact of the Human Papillomavirus

HPV infections are also contributing factors for both periodontal diseases and oropharyngeal cancer. Lim et al14 found that implementing early intervention for periodontitis with scaling and root planing reduced the risk of pharyngeal cancer, particularly in patients with a history of periodontitis longer than 3 years.

A significant relationship between P. gingivalis, periodontitis, and head and neck cancers exists.15 Both the severity and extent of chronic periodontitis may be considered potential risk indicators for oropharyngeal cancer even after adjustments for tobacco and alcohol use.16 Furthermore, self-reported poor oral hygiene is an independent risk factor for high-risk HPV infections.17 Thus, receiving adequate oral care may reduce the risk of periodontitis and oropharyngeal cancers.

Additional Contributing Factors

Although progress has been made in advancing oral health, challenges remain in securing long-lasting behavioral changes. Healthy habits, such as regular dental visits, proper nutrition, and sufficient oral self-care, are key to maintaining both good oral and overall health.1

Unhealthy habits also impact oral and systemic health. Tobacco use harms oral tissues and is directly implicated in oral cancer as well as in periodontal diseases. According to the US Surgeon General, the prevalence of cigarette smoking continues to decline.1 However, the use of e-cigarettes and vaping products for both tobacco and marijuana is rising.1 This new threat to oral health warrants close attention in its ramifications for oral and other cancers.

Additional risk factors for oral and systemic disease are mental illnesses or substance use disorders that hinder individuals’ ability to adequately perform oral hygiene and seek regular dental care.1 Alcohol is also a contributing factor for colorectal, oropharyngeal, and gastric cancers, as well as for periodontitis.5,9,16

Socioeconomic status, diabetes, age, gender, obesity, ethnicity, genetics, and diet also impact periodontitis and cancer risk. Dietary factors are associated with advanced tooth loss and may be related to cancer risk.18 It has been estimated that—for the 13 most common cancers in the US—31% could be prevented through a healthy diet, physical activity, and maintaining a healthy weight.19

innovative Methods to Supporting Oral Health

Myriad strategies are available to help patients improve their oral health. The use of prebiotics and probiotics is emerging as a supportive oral health measure.20 The role of probiotics in manipulating oral microbiota as a strategy to prevent oral disease is of intense interest. Enhancing the use of probiotic microorganisms as biotherapeutic agents may be a promising approach to achieving optimal oral health, however, more research is necessary.21

Host modulation therapy, which is intended to control and reduce local inflammation, may be helpful in supporting oral health and reducing systemic inflammation.21 Antimicrobial peptides can affect the homeostasis of the oral cavity by selectively killing bacteria, but they can also modulate both innate and adaptive immune responses through their immunomodulatory properties.20 Recent research shows that some antimicrobial peptide levels in saliva, such as LL-37, human neutrophil peptide 1–3, substance P, adrenomedullin, and azurocidin, are increased in individuals with periodontal diseases.20 Therefore, this method could be used either as a disease marker or to target specific oral bacteria.

Nutrition is integral to oral and systemic health. A mini-review determined that periodontal diseases are associated with deficiencies of vitamins A, B, C, D, and E, as well as folic acid, calcium, zinc, and polyphenols.22 Moreover, the antioxidant effects of vitamins and intake of anti-inflammatory drugs can positively impact the prevention and treatment of periodontal diseases and cancers by not only preventing the growth of new polyps but also stunting the growth of existing polyps.5,9

Analysis of salivary biomarkers offers potential in accurate diagnosis of both oral and systemic diseases.20 Several kits are available for chairside use to detect caries, periodontal diseases, and IL-6 polymorphism. A tool to help clinicians assess the risk of oral squamous cell carcinoma is also on the market. The development of techniques, such as liquid biopsies and saliva liquid biopsies, are currently under investigation and may offer promising results in cancer diagnosis.20

Conclusion

Oral health is key to maintaining overall health. Oral health professionals are charged with helping patients reach optimal oral health while making a difference in their overall health, as well. While many contributing factors affect oral and systemic diseases and their progression, the risk for periodontal diseases and cancer may be mitigated through education, proper diet, and a regular oral hygiene regimen.1,18

Bacteria alone are unable to induce cancer, but rather mutations in oncogenic signaling pathways due to an overly aggressive immune response caused by chronic inflammation are part of the process. The analysis of new preventive strategies along with improved diagnosis offered by salivary biomarkers have the potential to facilitate the diagnosis and prevention of periodontal diseases and cancer alike. Many microorganisms found in the oral cavity are also found in the colorectal and gastrointestinal tracts, and the oropharynx. Therefore, educating the public on the oral-systemic link along with how to maintain good oral health can help prevent both oral disease and cancer.

References

- National Institutes of Health. Oral Health in America: Advances and Challenges: Executive Summary. Available at: nidcr.nih.gov/sites/default/files/떕-12/Oral-Health-in-America-Executive-Summary.pdf. Accessed July 21, 2022.

- Morgan KK. How many people die of cancer a year. WebMD. Available at: webmd.com/cancer/how-many-cancer-deaths-per-year. Accessed July 21, 2022.

- Irfan M, Delgado R, Frias-Lopez J. The oral microbiome and cancer. Front Immunol. 2020;11:591088.

- Koliarakis I, Messaritakis I, Nikolouzakis TK, Hamilos G, Souglakos J, Tsiaoussis J. Oral bacteria and intestinal dysbiosis in colorectal cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:4146

- Șurlin P, Nicolae FM, Șurlin VM, et al. Could periodontal disease through periopathogen Fusobacterium nucleatum be an aggravating factor for gastric cancer? J Clin Med. 2020;9:3885.

- Farran M, Løes SS, Vintermyr OK, Lybak S, Aarstad H. J. Periodontal status at diagnosis predicts non-disease-specific survival in a geographically defined cohort of patients with oropharynx squamous cell carcinoma. Acta Oto-Laryngologica. 2019;139:309–315.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Chronic Diseases in America. Available at: cdc.gov/chronicdisease/resources/infographic/chronic-diseases.htm. Accessed July 21, 2022.

- Nazir M, Izhar F, Akhtar K, Almas K. Dentists’ awareness about the link between oral and systemic health. J Family Community Med. 2019;26:206–212.

- Marley AR, Nan H. Epidemiology of colorectal cancer. International journal of molecular epidemiology and genetics. Int J Mol Epidemiol Genet. 2016;7:105–114.

- Lee D, Jung KU, Kim HO, Kim H, Chun HK. Association between oral health and colorectal adenoma in a screening population. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e12244.

- Corbella S, Veronesi P, Galimberti V, Weinstein R, Del Fabbro M, Francetti L. Is periodontitis a risk indicator for cancer? A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:1–15.

- Nakatsu G, Li X, Zhou H, Sheng J, Wong SH. Gut mucosal microbiome across stages of colorectal carcinogenesis. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8727.

- Ortiz AP, González D, Vivaldi-Oliver J, et al. Periodontitis and oral human papillomavirus infection among Hispanic adults. Papillomavirus Res. 2018;5:128–133.

- Lim Y, Fukuma N, Totsika M, Kenny L, Morrison M, Punyadeera C. The performance of an oral microbiome biomarker panel in predicting oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancers. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2018;8:267.

- Chen PJ, Chen YY, Lin CW et al. Effect of periodontitis and scaling and root planing on risk of pharyngeal cancer: a nested case-control study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;18:8.

- Moraes RC, Dias FL, Figueredo CM, Fischer RG. Association between chronic periodontitis and oral/oropharyngeal cancer. Braz Dent J. 2016;27:261–266.

- Sun CX, Bennett N, Tran P, et al. A pilot study into the association between oral health status and human papillomavirus–16 infection. Diagnostics (Basel). 2017;7:11.

- Seneviratne CJ, Balan P, Suriyanarayanan T, et al. Oral microbiome-systemic link studies: perspectives on current limitations and future artificial intelligence-based approaches. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2020;46:288–299.

- Theodoratou E, Timofeeva M, Li X, Meng X, Ioannidis J. Nature, nurture, and cancer risks: genetic and nutritional contributions to cancer. Annual Review of Nutrition. 2017;37:293–320.

- Thomas C, Minty M, Vinel A, et al. Oral microbiota: a major player in the diagnosis of systemic diseases. Diagnostics (Basel). 2021;11:1376.

- Mahasneh SA, Mahasneh AM. Probiotics: a promising role in dental health. Dent J (Basel). 2017;5:26.

- Martinon P, Fraticelli L, Giboreau A, Dussart C, Bourgeois D, Carrouel F. Nutrition as a key modifiable factor for periodontitis and main chronic diseases. J Clin Med. 2021;10:197.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. August 2022; 20(8)38-41.