Sunstar Spotlight: Tips for Treating Facility-Based Patients

Dental hygienists are key care providers for these vulnerable populations.

Introduction

Manager, Professional Relations Sunstar Americas Inc

The United States Department of Health and Human Services’ report A Profile of Older Americans: 2012 states that the number of adults age 65 and older in the US reached 41.4 million in 2011 and is expected to more than double over the next 50 years. Of these individuals, approximately 1.5 million are living in longterm care facilities. The dental hygiene community has recognized the challenges of supporting the dental needs of these patients and, thus, has created numerous paths to help ensure access to quality dental care for this population. As many states implement changes to their practice acts in order to expand the roles of dental hygienists, new opportunities are available to meet the oral health needs of older adults.

This month’s Sunstar Spotlight features Dr. Bonnie Branson from the University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Dentistry. With her expertise in improving access to care for facility-based patients, Dr. Branson provides insight into the key issues affecting the provision of services to America’s seniors.

Dental practice acts are expanding across the United States, providing dental hygienists with direct access to patients in a variety of settings. As of January 2013, 35 states allow dental hygienists direct access to patients in some form.1 Dental hygienists in Iowa have been working under standing orders and written agreements with dentists to deliver services in schools, nursing facilities, free clinics, and other sites since 2004. Most recently, Kansas introduced the extended care permit III (ECP III) dental hygienist classification. ECP III dental hygienists can deliver expanded services in public health settings without direct supervision. For example, an ECP III dental hygienist may provide temporary soft reline to an ill-fitting denture in a long-term care facility, or remove decay with a hand instrument and fill the tooth with a temporary material in a school-based dental clinic.2

Such models of care often put dental hygienists in contact with people living in residential care facilities. Most individuals in long-term care residences have some form of moderate to severe cognitive or physical disability. Providing effective care to these patient populations is integral to maintaining both their oral and systemic health. Because these individuals are at increased risk of caries and periodontal diseases, prevention is critical.

According to the 2004 Nursing Home Survey, 16,100 nursing facilities house approximately 1.5 million residents in the US.3 With greater direct access, dental hygienists can now treat these patients within nursing facilities at place-based dental clinics using portable equipment.4 In order for this treatment to be successful, special care must be taken. Clinicians need to know how to provide services to patients with special needs, as well as understand which products—for dental hygienists, patients, and caregivers—will aid in the delivery of dental care and ongoing maintenance of oral health.

ORAL HEALTH STATUS

Individuals residing in nursing facilities frequently experience oral health problems, including xerostomia, gingivitis, periodontitis, angular cheilitis, and poor plaque control.5–7 The combination of dry mouth and poor plaque control creates the ideal environment for caries.8 A 2010 study found that 76% of patients residing in care institutions have root caries.9

ASSESSMENT

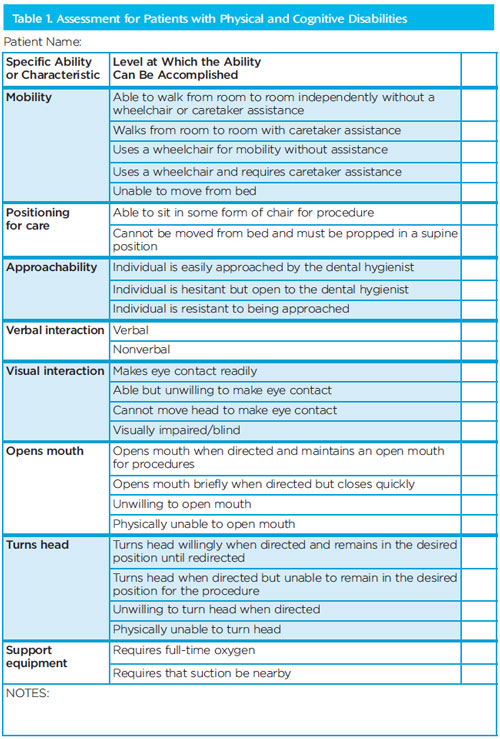

Dental professionals who provide services within residential facilities encounter patients of all ages living with a variety of physical and cognitive challenges, including those who have experienced a stroke, dementia, amputated limbs, cerebral palsy, or cognitive developmental deficits. Although many of the oral manifestations are similar, each patient is different; therefore, oral care must be tailored for patients on a case-by-case basis. Every person functions along a gradient of abilities, which the clinician must understand.10 In private practice, assessment begins after seating the patient. When treating patients residing in care facilities, however, clinicians must begin their assessment well before the patient is in the dental chair.11 A targeted assessment form (Table 1) offers oral health professionals a list of skills that must be evaluated prior to providing patient care.

Among patients with cognitive and physical disabilities, effective assessment, as well as obtaining access to the oral cavity, may be time consuming. With this in mind, initial appointments are typically designed to establish patient comfort in the dental setting. It must first be determined whether the patient can be treated in an on-site dental clinic or if care is best delivered bedside.

Once it is determined where the patient will receive services, oral health professionals need to consider a patient’s approachability. For example, does he or she make eye contact and is he or she able to communicate verbally? The answers to these questions will help determine the patient’s ability to cooperate in the dental setting, including maintaining an open mouth and following instructions. Care should not be started until the patient assessment is complete. With this information on hand, dental hygienists are better prepared to achieve positive appointments with their patients.

Oral care performed at residential facilities is often delivered using portable dental equipment set up in a community room or beauty salon. Several products are available to make the dental appointment more comfortable for both patients and clinicians. These include a wheelchair-reclining platform, various head pillows with cleanable coverings (Figure 1), and mouth props with uniquely designed suction tips (Figure 2).

IMPROVE ORAL HEALTH

While access to professional oral health care is key to facility residents, maintaining effective oral hygiene routines means the difference between health and disease. Plaque must be mechanically removed to prevent both dental caries and gingivitis, but motivating nursing home staff to provide routine oral care can often be challenging.11 To encourage staff to help residents with daily oral health care, and to support those who can accomplish these tasks independently, an armamentarium of helpful tools is available.

Power toothbrushes may be more effective at plaque removal among individuals with cognitive and physical disabilities.12 These types of brushes are either powered by an electrical charge or batteries. Typically, battery-powered brushes produce fewer cleaning stokes per minute, but they may be better suited for use in an institutional setting, due to the limited number of electrical outlets in patient rooms. Specialized manual brushes are also available to improve access to mouths with limited opening abilities and to facilitate brushing in noncooperative individuals.

Antimicrobial mouthrinses are also helpful in reducing bacterial plaque. Chlorhexidine gluconate (CHX) mouth rinses are the gold standard in plaque control.13–15 Today, there is also a nonalcohol CHX rinse available, which is a good choice for individuals with sensitivities to alcohol.16 CHX rinses require a prescription from a dentist, however, which may require special arrangements between staff, attending physicians, and the dentist. CHX is also not designed for long-term use. Therefore, patients using a CHX rinse need to be seen by their oral health provider on a regular basis (so that the use of the product can be adjusted). For those with limited understanding or physical control of oral tissues, the use of a mouth rinse can be challenging.

For these patients, applying CHX-soaked gauze on the oral tissue may be an effective alternative. A varnish containing both CHX and the essential oil thymol is also available. The use of varnish as the mode of delivery eliminates barriers for individuals who have difficulty using mouthrinses. However, the research on its efficacy is mixed, and it may not be cost-effective for many patients.17 Other antimicrobial mouthrinses may be helpful in reducing plaque and gingivitis.13–15 Rinses containing essential oils and cetylpyridinium chloride are available over-the-counter, which is helpful for these patient populations. A mouth rinse containing 0.2% delmopinol—an antiplaque agent that presents a surface barrier preventing oral bacteria from adhering to and colonizing on tooth surfaces and forming dental plaque—is also available over-the-counter.18 This rinse may be a beneficial addition to the self-care regimens of those who struggle with biofilm control.19

Fluoride varnish is highly effective at caries reduction and can be easily applied by caregivers.20 Varnishes that incorporate 22,500 ppm of sodium fluoride have been shown to arrest 78% of early root caries, and are recommended for use with at-risk older adults.21 Prescription-strength fluoride toothpastes and gels that contain 4,500 ppm to 5,000 ppm of sodium fluoride are recommended for daily use by vulnerable older adults, and have proven efficacy.21

The occurrence of dry mouth among institutionalized older adults and people living with disabilities is well documented.6,9 Medication use is often the cause of xerostomia. Taking frequent sips of water, using oral lubricating gels and saliva substitutes, and adjusting medication regimens may help alleviate dry mouth symptoms.22

CONCLUSION

In residential care facilities, it is typically the frequency and consistency of both care provision and product usage that makes the most difference in improving oral health as opposed to the specific products implemented. The provision of high-quality oral hygiene services in a long-term care facility depends on the coordination of on-site professional dental services, dedication to daily care routines, and cooperation of residents.23

Dental hygienists are increasingly able to provide services to patients residing in nursing facilities, and an arsenal of products and equipment is available to help clinicians provide the best care possible. The keys to developing successful treatment plans include customizing treatment based on patients’ abilities to participate in dental care; educating staff about performing effective oral hygiene; and arranging for dental services to be provided on-site.

REFERENCES

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association. Direct Access 2013 State Map. Available at:www.adha.org/ resources-docs/ 7524_ Direct_ Access_Map.pdf. Accessed October 3, 2013.

- Kansas Dental Board. Kansas Dental Practice Act. Available at: www.dental.ks.gov/docs/defaultsource/laws/kansas-dental-practices-act-(may-2013).pdf?sfvrsn=2. Accessed October 3, 2013.

- Jones AL, Dwyer LL, Bercovitz AR, Strahan GW. The National Nursing Home Survey: 2004overview. Vital Health Stat 13. 2009;167:1–155.

- Helgeson M, Glassman P. Oral health delivery systems for older adults and people withdisabilities. Spec Care Dentist. 2013;33:177–189.

- Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services. Adult Oral Health Assessment ExecutiveSummary. Available at: health.mo.gov/living/ families/oralhealth/ pdf/Adult_ Oral_ Health_Assessment_ Executive_Summary.pdf. Accessed October 3, 2013.

- Anders PL, Davis EL. Oral health of patients with intellectual disabilities: a systematic review.Spec Care Dentist. 2010;30:110–117.

- Kansas Department of Health and Environment. Elder Smiles 2012. Available at: www.kdheks.gov/ohi/download/2012_Elder_Smiles_Report.pdf. Accessed October 3, 2013.

- Turner MD, Ship JA. Dry mouth and its effects on the oral health of elderly people. J Am DentAssoc. 2007;138(Suppl 1):15S–20S.

- Ahluwalia KP, Cheng B, Josephs PK, Lalla E, Lamster IB. Oral disease experience of older adultsseeking oral health services. Gerodontology. 2010;27:96–103.

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry, Council on Clinical Affairs. Guideline on managementof dental patients with special health care needs. Pediatr Dent. 2012;34:160–165.

- Chen X, Clark JJ. Assessment of dentally related functional competency for older adults withcognitive impairment—a survey for special-care dental professionals. Spec Care Dentist.2013;33:48–55.

- Davies RM. The rational use of oral care products in the elderly. Clin Oral Investig. 2004;8:2–5.

- Osso D, Kanani N. Antiseptic mouth rinses: an update on comparative effectiveness, risks andrecommendations. J Dent Hyg. 2013;87:10–18.

- Rethman MP, Beltran-Aguilar ED, Billings RJ, et al. Nonfluoride caries-preventive agents:executive summary of evidence-based clinical recommendations. J Am Dent Assoc.2011;142:1065–1071.

- Van Strydonck DAC, Slot DE, Velden U, Weijden F. Effect of a chlorhexidine mouthrinse onplaque, gingival inflammation and staining in gingivitis patients: a systematic review. J ClinPeriodontol. 2012;39:1042–1055.

- Todkar T, Sheikh S, Byakod G, Muglikar S. Efficacy of chlorhexidine mouthrinses with andwithout alcohol—a clinical study. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2012;10:291–296.

- Leader D. Use of chlorhexidine varnish to prevent root caries may benefit some patients. J AmDent Assoc. 2013;144:1036–1037.

- Food and Drug Administration. 510(k) Summary. Available at: www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf5/k053166.pdf. Accessed October 29, 2013.

- Collaert B, Attström R, De Bruyn H, Movert R. The effect of delmopinol rinsing on dental plaqueformation and gingivitis healing. J Clin Periodontol. 1992;19:274-280.

- Raghoonandan P, Cobban SJ, Compton SM. A scoping review of the use of fluoride varnish inelderly people living in long term care facilities. Canadian Journal of Dental Hygiene. 2011;45(4):217.

- Gluzman R, Katz RV, Frey BJ, McGowan R. Prevention of root caries: a literature review ofprimary and secondary preventive agents. Spec Care Dentist. 2013;33:133–140.

- Perno Goldie M. Xerostomia and quality of life. Int J Dent Hyg. 2007;5:60–61.

- Walls AW, Meurman JH. Approaches to caries prevention and therapy in the elderly. Adv DentRes. 2012;24:36–40.

From Dimensions ofDental Hygiene. November 2013;11(11):19–22.