Strategies for Treating Children With Autism

A variety of strategies enable dental professionals to successfully provide much needed oral health care to this patient population.

This course was published in the October 2015 issue and expires October 31, 2018. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

Educational Objectives

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

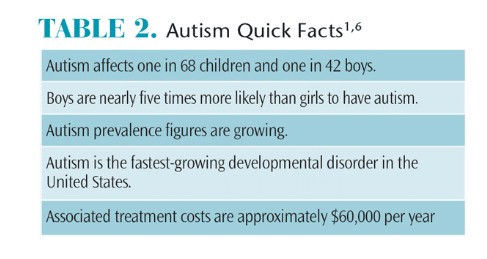

- Identify the prevalence of autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

- Discuss how to prepare for the safe and effective treatment of children with ASD.

- List the supportive accommodations that promote successful dental care for children with autism.

- Integrate adjunctive hygiene measures in self-care regimens.

With such a high prevalence rate, dental professionals will most likely encounter patients with autism during their career.2 Children with autism are at great risk for oral health problems, as up to 15% are not receiving dental care.7,8 This is partially because unusual behaviors and heightened sensory sensitivities can make receiving care difficult. Communication irregularities can also interfere in clinical interactions. Although these barriers can pose a challenge, treating children with ASD can be a manageable and enjoyable part of dental practice.

PREPARING FOR THE FIRST VISIT

For a child with autism, the dental visit can be overwhelming. Dental chairs that change positions, bright overhead lights, shiny instruments, and facial contact can seem scary and unusual. Not knowing how the child will react can be very stressful for parents/caregivers. In fact, it is not unusual for parents/caregivers to simply avoid taking their child to the dentist because they are worried the experience will be negative or they have already had a failure at other medical and dental offices.9

Practitioners can work with parents/caregivers to make the first visit pleasant. The parent/caregiver and child should not feel pressured to accomplish treatment on the initial visit. Rather, the first visit should provide an opportunity for the child to see the office and meet the staff. In many cases, when the child returns for subsequent visits, the fear of the unknown will be greatly diminished.

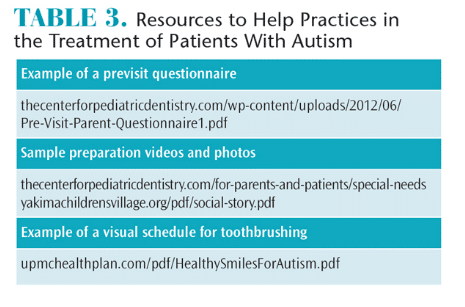

Likewise, the provider should take this opportunity to learn as much as possible about the patient. A previsit questionnaire is a simple way to quickly learn about the patient (Table 3). This gives parents/caregivers a chance to provide helpful information such as the child’s use and understanding of language, strengths and interests, and possible behavioral triggers. Including a section about the child’s previous history with dental treatment is also important. This will allow the team to use approaches that have proven successful for the child and avoid stressors that could stimulate the fight or flight response. The previsit questionnaire also allows parents/caregivers to voice their concerns and provide the clinician with information they think will be helpful.10 Nobody knows the child better than his or her parents/caregivers. As such, parents/caregivers can be very effective in interpreting the unique behaviors of their child.

When working with children who have ASD, it can be easy to focus on their limitations. Instead, try to capitalize on their strengths. For example, if a child is very visual, providing photos or a video of the office beforehand can be helpful (Table 3).11 These types of preparation aids are referred to as social stories, visual schedules, or storyboards.12,13 When creating a preparation aid, the child’s preferred media format should be considered. Some children will respond best if the aid is displayed on a tablet computer, while others might do better with a printed version. Some families develop preparation aids on their own, but it can be helpful to develop an office-specific aid that can be hosted on the practice’s website.

Many children with autism do better with established routines.14 Preparing at home helps children develop a dental routine that can be followed when they arrive at the office. Providing the family with a practice dental kit that may include exam gloves, gauze, and a plastic dental mirror is an effective strategy to facilitate this routine and increase compliance with the dental examination. Parents/caregivers should first establish a routine of brushing at home. Once established, the dental mirror can be introduced during this routine. Children then become accustomed to having items other than the toothbrush placed in their mouths. When they arrive at the dental office, parents/caregivers can demonstrate the home brushing technique and how they used the dental mirror. It is then much easier for the clinician to replicate the same toothbrushing technique and mirror examination.

ACCOMMODATING THE CHILD

Making accommodations to put the child at ease sets the stage for success. Families should be asked to bring the child’s favorite comfort objects to dental visits. Parents/caregivers might also consider bringing another adult who the child loves and trusts. Another adult can be helpful in keeping the child occupied, listening to information from the provider, or simply lending moral support.

Bringing additional help can be particularly useful if the child arrives early and needs to wait for an extended time. While every attempt should be made to seat the child on time, this is not always possible in a busy practice.15 It is important to determine the best location to wait. Some children will easily find ways to entertain themselves in a reception area, but others may be more at ease waiting in their car or taking a walk outside. Consideration should also be given to the examination area. Many children will do best, particularly for the initial visits, if they are scheduled in a private room.

Some patients will adapt easily to the dental routine, becoming comfortable with the office and dental team within the first few visits. Research indicates that up to half of children might fall into this category.16–20 Others may not accept dental care as readily. These children may benefit from applied behavioral analysis (ABA) therapy, which focuses on reinforcing desired behaviors and modifying undesirable ones, and desensitization.21,22 Many children with ASD are already enrolled in these types of therapies. Clinicians should ask parents/caregivers about strategies that have been successful in the past so clinicians know what rewards will be most effective and how often skills might be practiced.23 While a customized approach works best, the following type of program may work well for many patients:

- First visit: Meet and greet the dental staff. Review previsit questionnaire with parents/caregivers, discuss preparation aids, and provide practice exam kit. Attempt to have the child sit in a dental chair and take a photograph that can be viewed at home.

- Second visit: Child may sit in the dental chair while the parent demonstrates brushing technique and the use of the dental mirror. Provider then replicates parent technique.

- Third and subsequent visits: Repeat skills learned at last visit, while adding new skills.

It is important to introduce a new item or skill and then pause to give the child time to digest what has happened. In most circumstances, it is best to begin slowly and wait for the child to decide whether he or she will allow the next step. One technique is to first use an object like a dental mirror to count the clinician’s own gloved fingers. The child is then asked to have his or her fingers counted. Once the child is comfortable with the counting routine, the object can be moved to his or her lips or open mouth for the same count. Soon, the clinician has established a rapport with the patient and he or she has learned a new skill. It is extremely helpful to maintain the routine for all visits, including using the same order of procedures, the same operatory, and the same staff.

Children who are profoundly impaired or who cannot regularly make office visits may need advanced behavior guidance such as protective stabilization, sedation, or general anesthesia to provide care. If an office does not provide these services, a referral to a specialist or hospital-/university-based program is best.

For children with ASD, cooperation is often facilitated by clinicians who establish a calm energy and move at a steady pace. Using short simple sentences allows the child to absorb key messages. It is also important to avoid sarcasm, metaphor, and jargon, as patients with ASD tend to be very literal.24 For example, telling the patient to “hop up in the seat” may lead to bouncing in the dental chair. Perhaps most important is the clinician’s ability to be creative and maintain a sense of humor.

Children with autism may have sensory processing differences. If so, determining whether the child is a hyporesponder who seeks sensory input or a hyperresponder who avoids sensory input is helpful.25 Children who seek sensory input can be accommodated by applying deep pressure with a weighted blanket or X-ray vest, allowing the patient to view dental procedures using a hand-held mirror, and encouraging the child to squeeze toys during the visit. Children who avoid sensory input can be supported by minimizing noises, using unscented and unflavored products, placing dark glasses over the eyes to block out light, and reclining the dental chair in advance to minimize motion.14,26,27

MAINTAINING ORAL HEALTH

Regular oral surveillance is critical to maintaining the dental health of children with autism. Otherwise, caries can go undocumented and unchecked, causing pain that children may be unable to communicate to parents/caregivers. In turn, pain can contribute to negative behaviors, difficulty sleeping, and learning problems.28,29 These risks are minimized by establishing a routine of professional examination and preventive treatment.

Children with ASD have poorer oral hygiene than their peers, which may be complicated by sensory sensitivity experienced when brushing.30,31 Dental hygienists can encourage good brushing habits by asking a few important questions:

- Has the family tried both power and manual toothbrushes? Some children respond favorably to vibrations from power brushes, while others find these quite disconcerting. A multi-angled toothbrush can be helpful when parents/caregivers have limited time to brush.

- Does the child have a difficult time with the flavor of toothpaste? If so, different toothpastes should be tried to see if there is a flavor that is not bothersome. Alternatively, parents/caregivers can dip the brush in a fluoride mouthrinse. This won’t provide the same preventive effects as toothpaste, but it is better than not receiving any topical fluoride exposure at all.

- Does the child like numbers or timers? Brushing can sometimes be facilitated by using a timer. A standard hourglass or egg timer may work well for some children, while others might prefer a digital version. Novel toothbrush apps are also available.

- Does the child like music? Some toothbrushes play 2 minutes of music to motivate the child to brush for the appropriate amount of time.

- Does the child use visual schedules? If so, cards or visual schedules can be created for toothbrushing (Table 3).

- Where does the family usually brush the child’s teeth? For children who do not want to use the bathroom, brushing their teeth in the family room, while lying on the ground, or even in their beds may be more successful.

CONCLUSION

Providing dental care for children with ASD can be both a challenging and rewarding experience. By taking the time to work with families, oral health professionals not only provide needed dental services, but also contribute to the child’s ability to receive dental care and achieve a lifetime of good oral health.

REFERENCES

- Developmental Disabilities Monitoring NetworkSurveillance Year 2010 Principal Investigators; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder amongchildren aged 8 years—autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, United States, 2010. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2014;63:1–21.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Facts about Autism Spectrum Disorders. Available at: cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/facts.html. AccessedSeptember 16, 2015.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, Virginia: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

- Anderson DK, Lord C, Risi S, et al. Patterns of growth in verbal abilities among children with autism spectrum disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2007;75:594–604.

- Anderson KA, Shattuck PT, Cooper BP, Roux AM,Wagner M. Prevalence and correlates of postsecondary residential status among young adults with an autism spectrum disorder. Autism.2014;18:562–570.

- Autism Speaks. What Is Autism? Available at:autismspeaks.org/what-autism. Accessed September 16, 2015.

- Lai B, Milano M, Roberts MW, Hooper SR. Unmet dental needs and barriers to dental care among children with autism spectrum disorders. J AutismDev Disord. 2012;42:1294–1303.

- Lewis CW. Dental care and children with special health care needs: a population-based perspective. Acad Pediatr. 2009;9:420–426.

- Nelson LP, Getzin A, Graham D, et al. Unmet dental needs and barriers to care for children with significant special health care needs. Pediatr Dent.2011;33:29–36.

- Nelson TM, Sheller B, Friedman CS, Bernier R.Educational and therapeutic behavioral approaches to providing dental care for patients with autismspectrum disorder. Spec Care Dentist. 2015;35:105–113.

- Backman B, Pilebro C. Visual pedagogy in dentistry for children with autism. ASDC J Dent Child. 1999;66:294,325–331.

- Gray C. Social Stories 10.0: The new defining criteria. Available at: cp.iqnection.com/cms/downloadfile.php?file_id=141472. Accessed September 16, 2015.

- Gray C. Social Stories and Comic Strip Conversations With Students With Asperger Syndrome and High-Functioning Autism. New York: Plenium;1998.

- Kuhaneck HM, Chisholm EC. Improving dental visits for individuals with autism spectrum disorders through an understanding of sensory processing. Spec Care Dentist. 2012;32:229–233.

- Raposa KA. Behavioral management for patients with intellectual and developmental disorders. Dent Clin North Am. 2009;53:359–373.

- Marshall J, Sheller B, Williams B, Mancl L,Cowen C. Cooperation predictors for dental patients with autism. Pediatr Dent. 2007;29:369–376.

- Loo C, Graham R, Hughes C. Behaviour guidance in dental treatment of patients with autism spectrum disorder. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2009;19:390–398.

- Klein U, Nowak AJ. Characteristics of patients with autistic disorder (AD) presenting for dental treatment: a survey and chart review. Spec Care Dentist. 1999;19:200–207.

- Lowe O, Lindemann R. Assessment of the autistic patient’s dental needs and ability to undergo dental examination. ASDC J Dent Child. 1985;52:29–35.

- DeMattei R, Cuvo A, Maurizio S. Oral assessment of children with an autism spectrum disorder. J Dent Hyg. 2007;81:65.

- Connick C, Pugliese S, Willette J, Palat M.Desensitization: strengths and limitations of its use in dentistry for the patient with severe and profound mental retardation. ASDC J Dent Child. 2000;67:250-255.

- The Nancy Lurie Marks Family Foundation. The D-Termined Program of Repetitive Tasking and Familiarization in Dentistry. Available at: nlmfoundation.org/media/dental_clips.htm.Accessed September 16, 2015

- Maguire K, Lange B, Sherling M, Grow R. The use of rehearsal and positive reinforcement in the dental treatment of uncooperative patients with mental retardation. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities. 1996;8:167–177.

- Green D, Flanagan D. Understanding the autistic dental patient. Gen Dent. 2008;56:167–171.

- Stein LI, Polido JC, Cermak SA. Oral care and sensory over-responsivity in children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatr Dent. 2013;35:230–235.

- Marshall J, Sheller B, Mancl L, Williams B.Parental attitudes regarding behavior guidance of dental patients with autism. Pediatr Dent. 2008;30:400–407.

- Luscre D, Center D. Procedures for reducing dental fear in children with autism. J Aut Dev Disord. 1996;26:547–556.

- Edelstein B, Vargas C, Candelaria D, Vemuri M.Experience and policy implications of children presenting with dental emergencies to US pediatric dentistry training programs. Pediatr Dent.2006;28:431–437.

- Sheiham A. Dental caries affects body weight,growth and quality of life in pre-school children. Br Dent J. 2006;201:625–626.

- Sheiham A. Dental caries affects body weight,growth and quality of life in pre-school children. Br Dent J. 2006;201:625–626.

- Jaber M. Dental caries experience, oral health status and treatment needs of dental patients with autism. J Appl Oral Sci. 2011;19:212–217.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. October 2015;13(10):61–64.