Strategies for Managing Stress

Dental hygienists can use a variety of techniques to reduce the negative effects of stress.

Working in clinical dental hygiene can be stressful.1 Uncontrolled circumstances, such as pressure to stay on schedule and dealing with patient discomfort, impact dental hygienists’ stress levels. How dental hygienists perceive and react to these conditions impacts the intensity of their stress. Occupational stress combined with personal stress can lead to emotional and physical strain that may contribute to poor health and injury.2 Identifying stressors and learning appropriate coping mechanisms can help clinicians respond positively.

The National Institute of Mental Health identifies three categories of stressors: routine stressors commonly occurring in daily life with work and family responsibilities; sudden negative stressors caused by a job loss, divorce, or illness; or traumatic stressors caused by a major accident, war, or natural disaster.3 Routine work stressors include running late with a patient, waiting for a dentist to examine a patient, and technology overload. These stressors affect emotional, as well as physical health.2 Stress management techniques allow individuals to manage daily stressors in order to minimize health risks. Additional strategies may be needed when sudden negative or traumatic stressors occur.

Occupational stress in dentistry is related to illness, career burnout, and musculoskeletal disorders.1,2,4–6 According to O*Net, a website supported by the United States Department of Labor that provides occupational information, “Dental hygienists must have a high tolerance to stress in order to accept criticism and deal with high-stress situations.”7 As there are few studies that focus specifically on dental hygiene occupational stress, clinicians should proactively adopt stress management techniques to minimize the potential for emotional and physical problems. Dental hygienists should identify their own stressors and develop strategies to relieve them.

PHYSIOLOGICAL EFFECTS OF STRESS

Symptoms of stress include, but are not limited to, increased pulse rate, muscle tension, headaches, fatigue, muscle pain, clenching or grinding teeth, hand tremors, change in appetite, and insomnia. Stress impacts the autonomic nervous system, which affects heart rate, blood pressure, blood sugar levels, and digestive, reproductive, and immune systems. If stress is not controlled, it can lead to high blood pressure, cardiovascular issues, ulcers, musculoskeletal disorders, and other complications.8,9

Perceived stress signals the adrenal gland to release hormones, such as cortisol and adrenaline, creating the “fight-or-flight” response. This reaction increases respiration and pulse rates, as well as blood pressure. Stress will affect the most vulnerable body system, including cardiovascular, respiratory, endocrine, digestive, nervous, reproductive, and immune systems. Typically, individuals tighten muscles, creating tension and restricting breathing. The intensity of stress and its outcome on health are affected by the perception, reaction, and coping ability of the individual.8,9

Cumulative stress persists over several months, and even years, and can lead to anxiety disorders.10 In an acute response, once the stressor is resolved, the body will return to its normal resting state. In cumulative stress, however, the body never recovers from the acute fight-or-flight response, and, thus, heart rate and blood pressure remain elevated.8,9

Stress can be managed by initiating the parasympathetic nervous system to calm the body through breathing techniques, relaxation, and thought management.9,10 Various techniques can be implemented to manage stress throughout the day.

TIPS FOR MANAGING STRESS

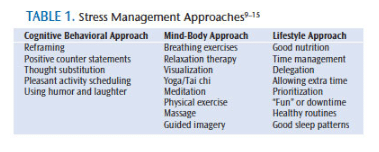

Stress management strategies can be implemented to control the effects of stressors and to help clinicians become more resilient to such stressors. There are generally three approaches to managing stressors: changing perception (cognitive behavioral approaches); controlling the reaction to the stressor (mind-body approaches); and adapting lifestyle to promote health (time management, diet, sleep patterns).9–11

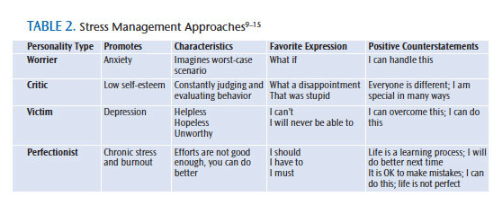

The first step to managing stress is self-awareness, which begins by identifying the physical, behavioral, or emotional signs that indicate stress. People perceive and react to stress differently; thus, a stressor for one person, such as procrastinating, may not be a stressor for another. Further, parts of the individual’s personality, or the personality of colleagues, can create a contagion of stress in a dental office where people work in close contact with others. For example, colleagues who over-worry promote anxiety; those who overcriticize may contribute to low self-esteem among colleagues; those who perceive themselves as victims encourage depression; and perfectionists promote chronic stress and burnout. While burnout occurs for many reasons, it is an occupational hazard for dental hygienists because they are often perfectionists.1,6 Choosing and implementing an approach or combination of approaches is crucial for effective stress management (Table 1).9–15

The second step involves looking closely at what causes the symptoms. A stress diary can help identify stressors, which may evolve in a pattern or at different times of the year, making it important to look for patterns of stress over an extended period vs a single day. In some cases, steps can be taken to eliminate certain stressors (eg, saying no to nonessential requests). When this is not possible, steps to manage the body’s responses to stressors need to be applied.9,10 The final step to managing stress is mitigating the effects of stress on the body and mind.

APPROACHES TO EFFECTIVELY MANAGE STRESS

Cognitive behavioral approaches change the perception of the stressor so it does not evoke an extreme reaction. A common example is reframing the perception of traffic, from a source of frustration to alone time with calming music. Reframing changes the way a person looks at an event, therefore changing the response. Similar approaches include positive counterstatements and thought substitution by thinking about something positive vs the negative effects of the stressor. Identifying the person’s character trait (worrier, critic, victim, or perfectionist) will facilitate selection and implementation of appropriate cognitive thoughts to achieve tranquility through positive counterstatements (Table 2).9–15 This type of thinking also keeps individuals focused on the positive aspects of a situation rather than the negative elements.10,11

Laughter relaxes the body and strengthens the immune system. Making light of situations and finding humor in them also eases stress.12,13 Focusing on an upcoming pleasant activity can lighten stressful situations. Including pleasant activities into one’s daily schedule has a positive effect on emotional health.9–15

Most often, individuals need to devise ways to react to stressors that will not jeopardize their own health. Physical activity can make use of the adrenalin that is released during stressful situations and alter serotonin levels. In fact, the body creates “endorphins” that act as its own calming mechanism. This is why taking a brisk walk, attending an exercise class, or even jumping rope can decrease the effects of stress. As everyone tenses muscles when stressed, stretching alone can relax the body—decreasing tightness, increasing blood flow, and lowering a state of high arousal or overalertness.9

Mind-body techniques are a cornerstone of stress management. They acknowledge the interconnection between the mind and body, so that calming the body also calms the mind, and vice versa. Mind-body interventions combine physical and mental practices to bring the nervous system back into balance, which reduces stress. Relaxation techniques—such as deep breathing, guided imagery, or the relaxation response—engage the body’s “rest-and-repair” mode rather than the fight-or-flight response.16

Yoga is a mind-body practice that has grown in popularity.14 While there are many different styles of yoga, all incorporate the mind-body connection through a series of poses and breathing exercises, which can be modified to fit individual abilities. Yoga and stretching with breathing exercises can be implemented into dental hygienists’ daily routines to relax and encourage proper body posture. Guided stretching with a video can be used to implement various yoga poses and stretching throughout the day.14,15

Committing to a routine of physical activity promotes wellness and decreases stress. Start gradually and stay committed. Keep a log of daily exercise, recording the date, time, type, duration, pulse rate, satisfaction level, and feelings about the exercise done that day.

A positive response to stressors starts with a healthy lifestyle, including getting enough sleep, making time for fun, eating well, and managing time efficiently. Time management techniques9 can be incorporated into daily lifestyle to balance work and home responsibilities. Time management strategies use planning tools to identify and organize demands based on when they are due. Planning tools include “to-do” lists, daily planners, personal calendars, and goal-setting initiatives; many smartphone apps also exist to help track and plan schedules. Ideally, important items are completed first. Momentum is gained through task completion, however, so even checking off simple items can become motivation for completing more challenging tasks. Some experts suggest organizing to-do lists according to roles of responsibility, such as parent, clinician, consultant, volunteer, etc. This approach helps to clarify importance of the task/time commitment.17

CONCLUSION

Occupational stress can lead to chronic stress, negatively affecting both mental and physical health. Adapting stress management approaches into the daily routine will enable clinicians to manage thoughts, emotions, and schedules for a healthy mind and body.

REFERENCES

- Gorter RC. Work stress and burnout among dental hygienists. Int J Dent Hyg. 2005;3:88–92.

- Warren N. Causes of musculoskeletal disorders in dental hygienists and dental hygiene students: A study of combined biomechanical and psychosocial risk factors. Work. 2010;35:441–454.

- National Institute of Mental Health. Adult Stress—Frequently Asked Questions. Available at: nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/stress/stress_factsheet_ln.pdf. Accessed October 21, 2014.

- Sanders MJ, Turcotte CM. Occupational stress in dental hygienists. Work. 2010;35:455–465.

- Newton JT, Gibbons DE. Levels of career satisfaction amongst dental healthcare professionals: Comparison of dental therapists, dental hygienists and dental practitioners. Community Dent Health. 2001;18:172–176.

- Lopresti S. Stress and the dental hygiene profession: risk factors, symptoms and coping strategies. Can J Dent Hyg. 2014;48:63–69.

- ONET Online. Detailed report for Dental hygienists. Available at: onetonline.org/link/details/29-2021.00#Abilities. Accessed October 21, 2014.

- Selye H. Stress Without Distress. New York: JB Lippincott Co; 1974.

- Quick, JC, Quick, JD. Nelson, DL, Hurrell, JJ. Preventive Stress Management in Organizations. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1997.

- Bourne EJ. The Anxiety & Phobia Workbook. 5th ed. Oakland, California: New Harbinger Publications Inc; 2010:40–57,177–248.

- Boyes A. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Techniques that Work. Available at: psychologytoday.com/blog/in-practice/201212/cognitive-behavioral-therapy-techniques-work. Accessed October 21, 2014.

- Mayo Clinic. Stress Relief from Laughter? It’s No Joke. Available at: mayoclinic.org/healthy-living/stress-management/in-depth/stress-relief/art-20044456. Accessed October 21, 2014.

- LaRoche L. You May Only Have a Few Minutes Left: Using the Power of Humor to Overcome Stress in Your Life and Work. New York: Hay House Inc; 2008.

- Gura ST. Yoga for stress reduction and injury prevention at work. Work. 2002;19:3–7.

- Moffitt Cancer Center. Gentle Yoga in Chair. Available at: youtube.com/watch?v=G8BsLlPE1m4. Accessed October 21, 2014.

- Pelletier KR. Mind as Healer: Mind as Slayer: A Holistic Approach to Preventing Stress Disorders. New York: Delta Books; 1977.

- Morgenstern J. Time Management from the Inside Out. 2nd ed. New York: Holt, Henry, & Co; 2004.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. November 2014;12(11):38–40.