Straight Talk About Hookah Smoking

A fog of misconceptions surrounds hookah use and its risks to both systemic and oral health.

This course was published in the November 2013 issue and expires November 30, 2016. The author has no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATOINAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Describe the origins and purpose of the hookah.

- List common misconceptions about hookah smoking.

- Identify the potential systemic and oral health effects caused by hookah use.

- Explain the dental hygienist’s role in educating the public about the dangers of hookah smoking.

The use of any kind of tobacco product is harmful to both systemic and oral health, and can lead to addiction. Oral health professionals are in the unique position to discuss and discourage all types of tobacco use, and they have a responsibility to educate their patients, as well as the general public, about its adverse effects on systemic and oral health. During these discussions, all types of tobacco use—including cigarettes, pipes, smokeless tobacco, and hookah smoking—must be addressed and the significant risk of nicotine addiction highlighted.

Out of all the oral health team members, dental hygienists often spend the most time with patients during their appointments, and they are well poised to provide tobacco cessation counseling. While the use of smokeless tobacco and smoking continues to decline, there is an increasingly popular tobacco trend—hookah, or waterpipe smoking. Dental hygienists should remain up to date on this growing pastime so they can effectively educate their patients about its potential risks.

WHAT IS HOOKAH SMOKING?

A hookah, also known as a shisha, nargile, maassel, boory, goza, arghileh, or hubble bubble, is a waterpipe made of glass used to smoke tobacco. The tobacco used for hookah comes in appealing flavors such as apple, cherry, coconut, mint, cappuccino, and chocolate—which masks the strong taste of its nicotine content. Hookah tobacco smoke is also pleasantly aromatic. This has made hookah smoking an increasingly popular tobacco trend of the 21st century, especially among young people.1

Hookah smoking is a 500-year-old tradition that originated in the Middle East. Egypt, India, and Turkey have long traditions of hookah smoking.2 Today, approximately 100 million people engage in hookah smoking worldwide.3 In some parts of the world, hookah is a common practice among children and young adults who might share a hookah with their family and friends.4 The World Health Organization (WHO) reports that it is not uncommon for children in Southwest Asia and North Africa to smoke tobacco with their parents.5 Currently in the United States, there are more than 300 hookah establishments.2

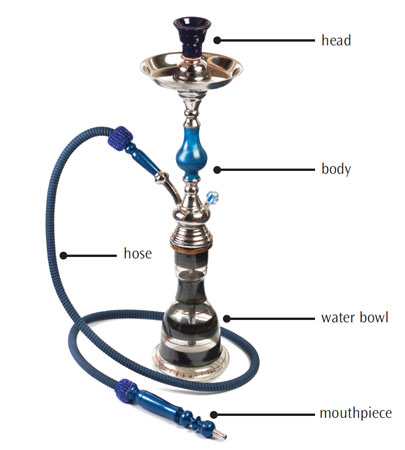

COMPONENTS OF A HOOKAH

There may be regional or cultural differences in the design of hookahs, though each generally includes the head, body, water bowl, hose, and mouthpiece (Figure 1). The head, which holds about 10 g to 20 g of tobacco, is attached to the body, which connects to the bowl. There is also a hose that has a mouthpiece affixed to the other end. To use the waterpipe, aluminum foil or a metal screen is placed over the head. Burning charcoal is placed on top of the tobacco.

During a hookah smoking session, the bowl is filled with water and tobacco smoke is drawn up through the hose and inhaled into the mouth of the user.6

TARGET AUDIENCE

The waterpipe was invented by a 16th century physician in India, who claimed that passing the tobacco smoke through water would render it harmless.3 This unsubstantiated belief is still commonly held. In the US, hookah smoking primarily appeals to young adults between the ages of 18 to 24. It is estimated that 10% to 20% of college students use hookah either in bars, lounges, or at home.3 In 2011, approximately 19% of 12th-grade students had used a hookah in the past year.7 A cross-sectional study that looked at 307 Facebook profiles of students at two large American universities found that 27.8% endorsed hookah smoking with users reporting smoking tobacco, hash, and marijuana in their hookahs.8 Results also showed that cigarette smoking was more common among the hookah users than nonhookah users.8 Educating young people about the risks of hookah smoking is imperative because the seeds of addiction are planted during adolescence.9

MISCONCEPTIONS

Many users mistakenly believe that the tobacco used in hookah smoking is either harmless or less harmful and less addictive than cigarette smoking.10 Because many young adult/teenage users in the US may not use the hookah often, they do not see it as a health risk. Some believe that they can stop using the hookah at any time.

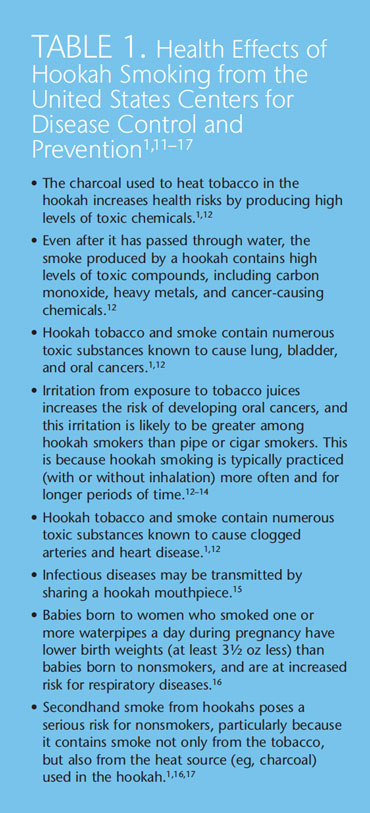

The truth is that hookah smoking is no less harmful than other forms of tobacco use, and it, most definitely, exerts negative health effects on its users (Table, presents a summary).1,11–17 Many hookah uses assume that the practice is relatively safe because the tobacco smoke has first passed through the water.5 The water filtration system, however, only cools the smoke, enabling the user to inhale a greater amount of smoke over a longer period of time than is typical of traditional smoking practices. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) states that “even after it has passed through water, the smoke produced by a hookah contains high levels of toxic compounds, including carbon monoxide, heavy metals, and cancer-causing chemicals.”11 Repeated inhalation of tobacco smoke only increases the exposure to carcinogens, and, while the water may absorb some of the nicotine, users are still at risk for addiction. The misconception that waterpipe smoking is not as addictive as cigarettes is widespread.8 However, a clinical study examining nicotine and nicotine levels after using a waterpipe showed high levels of both substances in the blood and saliva of users.18

Not only does waterpipe smoke contain many of the same toxins found in cigarette smoke,5 the use of charcoal to heat tobacco in the waterpipe increases the resultant health risks.11 The combination of charcoal and tobacco can produce high levels of toxic chemicals that may be carcinogenic,11 causing serious harm to the lungs and other parts of the body.

Hookah smoking requires the user to inhale a larger volume of smoke during a single session compared to cigarette smoking. The volume of smoke inhaled during a typical hookah session is approximately 90,000 mL compared to the 500 mL to 600 mL inhaled from smoking one cigarette.11 This is because puffs from the waterpipe are generally larger than puffs from a cigarette. During the activity of waterpipe smoking, which typically lasts 30 minutes to 1 hour, the smoker may take 50 puffs to 200 puffs. In fact, hookah users may inhale as much smoke during one session as a cigarette smoker would inhale consuming 100 or more cigarettes.4

Hookah smoking is not only a concern for users, but also for those exposed to its secondhand smoke.19 The CDC notes that the secondhand smoke generated by hookah smoking exerts significant health effects on nonsmokers, as it also contains smoke from charcoal—the original heat source.11 Hookah bars in which waterpipes are smoked are becoming abundant across the US, with an estimated opening of 200 to 300 locations since 2000.18 The air inside of hookah lounges or bars may contain high concentrations of secondhand smoke, creating hazardous conditions for patrons and employees. In a study that assessed the level of secondhand smoke emitted by hookah smoking, Fiala et al20 evaluated the indoor air quality of 10 hookah lounges in the state of Oregon. The measurements determined that the air quality in all of the establishments was unacceptable, generating ratings from “unhealthy” to “hazardous” on the US Environmental Protection Agency scale. The authors surmised that these levels created potential negative health effects for customers, as well as employees.20

Even with these misconceptions exposed, hookah establishments are widely unregulated—making it easy for young adults to frequent them and engage in this smoking activity. The many statewide smoke-free regulations currently in place often do not address hookah smoking specifically. Primack et al21 found that while 73 of the biggest American cities prohibit cigarette smoking inside of bars, 69 make an exception for hookah smoking. Four of the 69 cities have created legislation specifically exempting hookah smoking from traditional tobacco regulations. 21 A change in public policy is necessary to prevent secondhand exposure to this form of tobacco smoke.

ORAL AND SYSTEMIC HEALTH CONCERNS

Hookah smoking has been linked to oral, bladder, lung, stomach, and esophageal cancers; respiratory disease; reduced lung function; decreased fertility; and low birthweight in babies.15 In a study of 16 subjects, Jacob et al found that hookah smokers had substantial increases in plasma nicotine concentrations similar to those experienced during cigarette smoking; however, increases in carbon monoxide levels were significantly higher among hookah smokers than those generated by cigarette smoking.3 The absorption of nicotine in amounts comparable to or greater than cigarette smoking may indicate a strong risk for addiction from hookah smoking.

Cigarette smoking raises the risk of the following problems in the oral cavity: oral squamous cell carcinoma, oral leukoplakia, periodontal diseases, tooth loss, gingival recession, and smoker’s leukoplakia or smoker’s palate (Figure 2).22 It is logical to assume that the risks faced by hookah smokers are similar to those experienced by cigarette smokers and users of other tobacco products.

Young smokers are more likely to develop severe periodontal problems than nontobacco users,19 and a literature review found that hookah smoking was significantly associated with periodontal disease development.23 Tobacco use can also affect wound healing and interfere with the successful outcomes of oral disease treatment.

The shared use of the hookah pipe also presents health concerns. Hookah smoking is a group activity, with individuals sharing a single pipe and, often, the same mouthpiece.11 This communal use raises the risk of spreading infectious diseases or harmful transmissible microorganisms, such as tuberculosis and the herpes, influenza, hepatitis A, and hepatitis B viruses.15

Tobacco juice irritates the oral cavity, raising the risk of oral cancer.2,11,12 Because hookah smoking is practiced for longer periods of time than other forms of tobacco use, this oral cancer risk may be even greater among hookah users.2,11,12 The length of hookah smoking sessions, in addition to the frequency of use, affect the level of risk for both systemic and oral complications.

DENTAL HYGIENISTS AND TOBACCO CESSATION

The use of tobacco in the United States continues to decline, and significant progress has been made among young people. Researchers from the CDC’s Office on Smoking and Health recently published a study that looked at trends in tobacco use among high school students from 2000 to 2012.24 The data, collected from the National Youth Tobacco Survey, showed that high school students’ use of any type of tobacco product declined from 33.6% in 2000 to 20.4% in 2012, with the most significant reductions noted among those who reported smoking cigarettes only. The authors suggest that more research is needed in order to effectively develop prevention and control protocols that address other forms of tobacco use.24

Because hookah smoking uses flavored tobacco and appears to be a fun social activity, tobacco cessation experts are concerned that it will entice a new generation of tobacco users, and may lead to an increase in cigarette smoking. Dental professionals should assess their patients’ use of tobacco products at each visit, which can be obtained through the medical/dental history form and by talking with patients about their lifestyle choices. Education is the key to continuing the downward trend in tobacco utilization. Thus, more study is warranted on the health effects of hookah smoking, as well as appropriate strategies to deter its use. Both medical and dental professionals must be involved in educating patients about the dangers of all forms of tobacco use.

A Cochrane review25 sought to investigate the efficacy of tobacco cessation efforts among waterpipe smokers but could find no randomized controlled trials on the subject. The authors suggest that more research is needed on the addictiveness of hookah smoking and associated health effects among both users and those exposed to secondhand smoke, in addition to well designed studies on treatments designed to cease this type of tobacco use.25

Although programs designed specifically for hookah smokers are still being investigated and developed, the American Dental Hygienists’ Association has extensive tobacco cessation programming available free of charge on its website www.askadviserefer.org. See Table 2 for an example of a 3-minute tobacco cessation intervention that can be useful for all types of tobacco users.26

As oral health professionals, dental hygienists are in a unique position to reach out into the community to educate the public, especially adolescents and young adults, about the dangers of hookah smoking. Dental hygienists can participate in health fairs, community outreach activities, and address this issue in schools and universities. Clinicians can become advocates for change in policy promoting new laws or amendments to existing legislation to curb hookah use. It was the initiation of wide-reaching public policy that curbed the affordability and accessibility of cigarettes, which helped reduce smoking among young people by nearly 50% between 1998 and 2009.7,27 Pushing for public policy that eliminates exemptions for hookah lounges under current smoke-free legislation; requires the clear labeling of hookah tobacco and inclusion of health warnings on every package; extends current bans on flavoring tobacco in cigarettes to the tobacco used in hookah smoking; and furthers regulation on the shipment of hookah tobacco can help curtail this dangerous trend.7 Hookahs should be regulated in the same manner as cigarettes and other tobacco products. These avenues serve as an important opportunity for the oral health profession to educate the public—primarily youths—about the true dangers of hookah smoking.

REFERENCES

- American Lung Association. Tobacco PolicyTrend Report: An Emerging Deadly Trend:Waterpipe Tobacco Use. Available at: www.lungusa2.org/ embargo/ slati/ Trendalert_ waterpipes.pdf.Accessed October 23, 2013.

- The Bacchus Network. Top Facts: Hookah.Available at: tobaccofreeu.org/cms-assets/documents/120710-860548.hookah.pdf.Accessed October 28, 2013.

- Jacob P 3rd, Abu Raddaha AH, Dempsey D,et al. Nicotine, carbon monoxide, andcarcinogen exposure after a single use of a waterpipe. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev.2011;20:2345–2353.

- Gatrad R, Gatrad A, Sheikh A. Hookahsmoking. BMJ. 2007;335:20.

- World Health Organization. TobReg AdvisoryNote. Waterpipe Tobacco Smoking: HealthEffects, Research Needs and RecommendedActions by Regulators. Available at: www.who.int/tobacco/global_interaction/tobreg/Waterpipe%20recommendation_Final.pdf. Accessed October 23, 2013.

- National Cancer Institute, National Institutes ofHealth. A Harmful Trend: Increased WaterpipeSmoking. Available at: benchmarks.cancer.gov/2010/05/a-harmful-trend-increased-waterpipesmoking/.Accessed October 23, 2013.

- Morris DS, Fiala SC, Pawlak R. Opportunitiesfor policy interventions to reduce youth hookahsmoking in the United States. Prev Chronic Dis.2012;9:E165.

- Brockman LN, Pumper MA, Christakis DA,Moreno MA. Hookah’s new popularity amongUS college students: a pilot study of thecharacteristics of hookah smokers and theirFacebook displays. BMJ Open. 2012;2:e001709.

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG,Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future, NationalResults on Adolescent Drug Use: Overview ofKey Findings, 2009. Bethesda, Md: NationalInstitute on Drug Abuse; 2010.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.Use of cigarettes and other tobacco productsamong students aged 13-15 years—worldwide,1999-2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep.2006;55:553–556.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.Smoking and Tobacco: Hookahs. Available at:www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/tobacco_industry/hookahs/. Accessed October23, 2013.

- Cobb C, Ward KD, Maziak W, Shihadeh AL,Eissenberg T. Water pipe tobacco smoking: anemerging health crisis in the US. Am J HealthBehav. 2010;34:275–285.

- Nuwayhid IA, Yamout B, Azar G, Kambris MA.Narghile (hubble-bubble) smoking, low birthweight and other pregnancy outcomes. Am JEpidemiol. 1998;148:375–383.

- El-Hakim IE, Uthman MA. Squamous cellcarcinoma and keratoacanthoma of the lowerlips associated with “goza” and “shisha” smoking.Int J Dermatol. 1999;38:108–110.

- American Lung Association. HookahSmoking: A Growing Threat to Public Health.Available at: www.lung.org/stop-smoking/tobacco-control-advocacy/reports-resources/cessation-economic-benefits/ reports/ hookahpolicy-brief.pdf. Accessed October 23, 2013.

- Department of Health and Human Services.Preventing Tobacco Use Among Youth andYoung Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General.Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control andPrevention, Office on Smoking and Health; 2012.

- Cobb CO, Vansickel AR, Blank MD, Jentink K,Travers MJ, Eissenberg T. Indoor Air Quality inVirginia Waterpipe Cafés. Tob Control. 2013;22:338–343.

- Noonan D, Kulbok PA. New tobacco trends:waterpipe (hookah) smoking and implicationsfor healthcare providers. J Am Acad Nurse Pract.2009;21:258–260.

- Wilkins E. Clinical Practice of the DentalHygienist.11th ed. Baltimore: Lippincott,Williams & Wilkins; 2012.

- Fiala SC, Morris DS, Pawlak RL. Measuringindoor air quality of hookah lounges. Am JPublic Health. 2012;102:2043–2045.

- Primack BA, Hopkins M, Hallett C, et al.US health policy related to hookah tobaccosmoking. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:e47–51.

- Frei M, Engel Brügger O, Sendi P, Reichart PA,Ramseier CA, Bornstein MM. Assessment ofsmoking behaviour in the dental setting. A studycomparing self-reported questionnaire data andexhaled carbon monoxide levels. Clin OralInvestig. 2012;16:755–760.

- Akl EA, Gaddam S, Gunukula SK, HoneineR, Jaoude PA, Irani J. The effects of waterpipetobacco smoking on health outcomes: asystematic review. Int J Epidemiol.2010;39:834–857.

- Arrazola RA, Kuiper NM, Dube SR. Patternsof current use of tobacco products among UShigh school students for 2000-2012—findingsfrom the National Youth Survey. J AdolescHealth. 2013 Sep 25. Epub ahead of print.

- Maziak W, Ward KD, Eissenberg T.Interventions for waterpipe smoking cessation.Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;4:CD005549.

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association.Tobacco Cessation Program for the DentalPractice. Available at: www.askadviserefer.org/downloads/Tobacco_Cessation_Protocols.pdf.Accessed October 29, 2013.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.Cigarette use among high school students—United States, 1991–2009. MMWR Morb MortalWkly Rep. 2010;59:797–801.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. November 2013;11(11):62–66.