Starting Out Right

The importance of infant oral health care and disease management.

This course was published in the May 2009 issue and expires May 2012. The author has no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Understand the basic etiology of caries in early childhood.

- Identify components of infant oral health care.

- Provide basic anticipatory guidance and appropriate referrals.

While a general decline of dental caries among the American population has occurred over the past decade, a recent national survey indicates an increased prevalence of dental caries in primary dentition among children aged 2 to 5 years.5 The absence of timely information on proper oral health care and a lack of early access to dental care for children who have high caries risk have contributed to the severity of this public health problem. To combat this issue, the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD) has recommended that “all primary health care professionals who serve mothers and infants should provide parent/ caregiver education on the etiology and prevention of early childhood caries (ECC). Oral health counseling during pregnancy is especially important for the mother.”6

Understanding the etiology of ECC, oral health risk assessment, anticipatory guidance, and early caries prevention and intervention are essential components of infant oral health care and disease management and should be integrated into the curriculum of all dental, medical, nursing, and allied health care professional programs.

ETIOLOGY OF CARIES IN EARLY CHILDHOOD

Dental caries is a transmissible, infectious bacterial disease of the teeth7 and is a result of an imbalance of multiple risk factors and protective factors over time. The caries process involves an overgrowth of normally occurring human oral flora, predominately mutans streptococci, and fermentable carbohydrates leading to acid demineralization of dental structures. Several protective factors in the oral cavity, such as saliva and fluoride, mediate the process and the interplay of the pathological factors (bacteria and carbohydrates) and protective factors on teeth dictate the expression of dental disease over a period of time.

Human dental flora are site specific and do not colonize in the oral cavity until the eruption of the primary dentition. The acquisition of mutans streptococci occurs at an average age of approximately 2 years.8 The most common route of bacterial transmission is from mother (vertical colonization) or caregiver to infant.9-11 Carious lesions can develop as soon as teeth erupt, and caries in early childhood usually have a unique presentation, eg, smooth surface lesion, with aggressive and virulent nature and rapid progression. Signs of early caries initially appear as chalky white spots or lines on intact enamel surfaces and typically occur on the maxillary incisors. Cavitated lesions may occur as early as 10 months of age.12

Human dental flora are site specific and do not colonize in the oral cavity until the eruption of the primary dentition. The acquisition of mutans streptococci occurs at an average age of approximately 2 years.8 The most common route of bacterial transmission is from mother (vertical colonization) or caregiver to infant.9-11 Carious lesions can develop as soon as teeth erupt, and caries in early childhood usually have a unique presentation, eg, smooth surface lesion, with aggressive and virulent nature and rapid progression. Signs of early caries initially appear as chalky white spots or lines on intact enamel surfaces and typically occur on the maxillary incisors. Cavitated lesions may occur as early as 10 months of age.12

Early childhood caries is generally defined as the presence of one or more decayed (noncavitated or cavitated lesions), missing (due to caries), or filled tooth surfaces in any primary tooth in a child 71 months of age or younger.13,14 Although the severity of ECC may be associated with poor feeding habits— and thus was traditionally known as “baby bottle syndrome” or “nursing decay”—these terms may not truly reflect the multifactorial etiology of the disease process.15 Although the severity of ECC may be associated with poor feeding habits this term may not truly reflect the multifactorial etiology of the disease process.15 Early inoculation of bacteria in the primary dentition, frequent bottle feeding at night, frequent sugar consumption and snacking, poor oral hygiene, enamel hypoplasia, and other associated factors may predispose infants to develop ECC.8,16-19 If caries activity continues to progress rapidly without intervention, severe early childhood caries (S-ECC) and extensive loss of dental structure may occur at a relatively early age (Figure 1).

Early signs of dental caries in infants and toddlers are associated with a child’s caries risk and indicate a potentially high caries incidence in the future. ECC can be a costly, devastating disease in children with detrimental effects on the dentition and may lead to other health issues, such as malnutrition, subnormal weight, and iron deficiency.20,21

PRENATAL VISIT

Prevention of ECC begins with oral health counseling and modification of maternal oral health during the prenatal and perinatal periods.22 Maternal oral health is linked to future dental health of the infant and may also affect the infant’s systemic health.23-25 For example, periodontitis in pregnant woman may be associated with an increase risk of premature birth.26,27 Medication intake during pregnancy may lead to intrinsic discoloration of developing dentition. Counseling should be provided to the expecting parents, and the mother should be evaluated for signs of dental caries and periodontal diseases periodically. Active carious lesions and periodontal diseases should be treated in a timely manner. Proper oral hygiene care and optimal dietary intake with reduced frequency of sugar consumption should be advised.

PRIOR TO ERUPTION OF PRIMARY DENTITION

Newborns and infants should be evaluated for any oral or dental abnormalities, such as eruption cyst and natal teeth (teeth present at birth), and referred for proper intervention. An oral health risk assessment should be performed and an appropriate preventive plan should be developed based on potential risk variables. In the initial counseling, appropriate anticipatory guidance should be given, and emphasis should be placed on proper nutritional intake.

Human breast milk provides the best nutritional source for infants and breastfeeding alone may not be cariogenic. However, human breast milk in combination with other carbohydrates and formula milk with high sugar content can be highly cariogenic.28 Fruit juice is highly discouraged. If the infant is bottle-fed, the caregiver should hold the infant when feeding, and the bottle should not be propped or placed in the bed. The bottle should contain only milk or water. Feeding throughout the night—whether frequent bottle feeding or breastfeeding on demand—has been associated with ECC.29 Prior to the eruption of dentition, gum and surrounding soft tissue should be cleaned and wiped with damp cloth after each feeding to optimize the oral health.

ERUPTING PRIMARY DENTITION

The first clinical sign of tooth eruption is blanched mucosa tissue, and the toddler may exhibit symptoms of irritability, slight temperature increase, and increased sucking. Drooling is a common finding at this age and may not be related to teething. Sucking on soft washcloths or teething rings may help relieve teething discomfort. Mandibular primary central incisors are normally the first teeth to emerge in the oral cavity and the timing for eruption is around 6 months to 8 months. A child should be evaluated for the eruption pattern, and the caregiver should be advised on proper tooth eruption sequence, timing, and oral facial development.

The role of fluoride in tooth formation and caries prevention is well documented.30-36 Proper evaluation of the child’s need for fluoride supplements or topical fluoride treatments is critical, as excessive fluoride may lead to unesthetic fluorosis or fluoride toxicity. Systemic fluoride supplementation for a child is based on the fluoride concentration in drinking water and the child’s age. If the fluoride concentration in the drinking water is below the optimal level supplemental fluoride in liquid suspension should be prescribed. Systemic fluoride is not dispensed to children younger than 6 months of age regardless of the fluoride level of drinking water. Fluoridated bottled water is also available for those children who are not exposed to an optimal level of fluoride.

Maternal oral health should be monitored periodically as it significantly influences the risk of dental disease in a child.37,38 The mother should maintain optimal dental health and oral hygiene practices to reduce plaque bacterial levels and consequently reduce transmission and opportunity for early microbial colonization in the child’s oral cavity. Studies indicate that the timing of bacterial colonization is associated with caries development.39 The practice of sharing utensils, cups, or food between caregiver and infant is highly discouraged because saliva serves as an ideal medium for bacterial transmission. To minimize the mother’s bacterial load, she should be advised on appropriate dietary habits and frequency of snacking, cariogenicity of certain foods and beverages, proper oral hygiene, and the use of supplemental fluoride products. Salivary bacterial levels and flow rate should be tested and monitored.

Recent evidence also suggests that the incidence of caries in a child can be significantly reduced when a mother chews four pieces of xylitol gum per day.25,40 More important, the mother should seek routine professional oral health evaluation, obtain dental prophylaxis and topical fluoride application, and be treated for any gingival disease and dental caries.

A child should receive an initial dental examination within 6 months of the first tooth eruption and no later than 12 months of age.41 Dental decay can be well advanced by age 3. Dental examination at an early age provides an opportunity for the health care provider to detect early oral and dental disease, such as ECC, and to provide timely intervention and appropriate referral, if needed, thereby eliminating extensive and costly treatments in the future, enhancing school readiness, and improving the child’s general health and wellbeing. The examination should consist of evaluating the oral facial development, erupting pattern of teeth, occlusion relationship, integrity of oral tissue, plaque level, and disease of dental structure. Enamel hypoplasia may be observed in children with low birth weight or systemic illness during early infancy.42

A child should receive an initial dental examination within 6 months of the first tooth eruption and no later than 12 months of age.41 Dental decay can be well advanced by age 3. Dental examination at an early age provides an opportunity for the health care provider to detect early oral and dental disease, such as ECC, and to provide timely intervention and appropriate referral, if needed, thereby eliminating extensive and costly treatments in the future, enhancing school readiness, and improving the child’s general health and wellbeing. The examination should consist of evaluating the oral facial development, erupting pattern of teeth, occlusion relationship, integrity of oral tissue, plaque level, and disease of dental structure. Enamel hypoplasia may be observed in children with low birth weight or systemic illness during early infancy.42

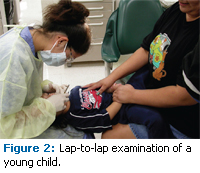

The child should be examined in a lapto- lap position (Figure 2) or a supine position in a dental chair to allow for adequate visualization of dental and oral soft tissues. Any discomfort or pain should be evaluated, and parental concerns should be addressed. Supplemental diagnostic aids, such as radiographs, may be needed in the assessment of underlying pathology. Early childhood dental visits also offer opportunities to provide oral health education and anticipatory guidance for caregivers, development of a preventive strategy based on oral health risk assessment, and determination of an appropriate interval for periodic examination and routine dental prophylaxis. A concentrated topical fluoride application, such as fluoride varnish, should be applied to young primary dentition in children who have existing ECC or are at high caries risk during each periodic evaluation visit. Apprehensive children can also benefit from visiting a dental office at an early age, as continued and repetitive dental visits may familiarize them with the dental setting and alleviate anxiety and fear of visiting dentists in the future.

Children are in a constant state of change in physical growth and mental development. A developmentally appropriate anticipatory guidance should be advised based on a child’s age and state of development. Practical information and counseling should be provided to parents about relevant topics, such as injury prevention, feeding and oral habits, oral hygiene, nutritional intake, and speech development.

Prior to developing manual dexterity and the ability to perform simple tasks of personal hygiene, a child’s home oral care is the responsibility of the parents. After the eruption of the first tooth, dentition should be cleaned with an appropriate size, soft-bristle toothbrush, and a smear layer of fluoridated toothpaste should be used (Figure 3). Excessive toothpaste should be wiped off with a damp cloth. Xylitol wipes may be used to clean dentition and the oral cavity after each feeding. As a child gets older and develops appropriate skills, instructions on proper oral hygiene technique, including brushing twice daily with small pea-sized amounts of fluoridated toothpaste and dental flossing, should be provided to both parent and child.

Parents need to supervise home oral hygiene until the child has demonstrated the ability to perform personal hygiene effectively and independently. The effectiveness of oral hygiene practice should be monitored, discussed with parents, and reinforced at every periodic dental visit.

By now, parents should be familiar with the role of carbohydrates in caries initiation and the development of ECC. They should be made aware of the other health issues—such as obesity—related to excess consumption of carbohydrates and sweetened carbonated beverages. Nutritional counseling based on the United States Department of Agriculture’s Food Pyramid should be provided to parents with an understanding of the relationship between a healthy diet and a child’s development. A child’s daily nutritional intake should be reassessed at each periodic evaluation visit, and proper dietary choices promoting oral health should be discussed with the parents. To minimize the risk of developing ECC, the timing of bottle feeding or breastfeeding should be restricted to meal times and not on demand or while the child is sleeping. Sugarcoated pacifiers may also be associated with ECC. Drinking between meals should be limited to water or unsweetened milk, and juice should be restricted to meal times with no more than 4 oz to 6 oz per day.43 Children are encouraged to use a sippy cup by 6 months of age and should wean from the bottle or breastfeeding by the age of 12 months.

The AAPD recommends that every infant should have a dental home and an established source of dental care by 12 months of age.44-46 A thorough medical history of the infant and a dental history of both infant and primary caregiver, in particular the mother, should be recorded. The dental care provider should conduct a thorough oral examination, assess the infant’s risk of developing dental disease, determine an appropriate prevention plan and interval for periodic reevaluation, provide anticipatory guidance, plan for comprehensive care, and refer patients to the appropriate health care professional if needed.

REFERENCES

- United States Public Health Service. Oral Health in America: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, Md: Department of Health and Human Services; 2000.

- Tang JM, Altman DS, Robertson DC, O’Sullivan DM, Douglass JM, Tinanoff N. Dental caries prevalence and treatment levels in Arizona preschool children. Public Health Reports. 1997; 112:319-329, 330-331.

- Pierce KM, Rozier RG, Vann WF Jr. Accuracy of pediatric primary care providers’ screening and referral for early childhood caries. Pediatrics. 2002;109(5)e82.

- Brunelle JA. Caries attack in the primary dentition of U.S. children. J Den Res. 1990;69:180.

- Dye BA, Tan S, Smith V, et al. Trends in Oral Health Status: United States, 1988-1994 and 1999- 2004. Hyattsville, Md: National Center for Health Statistics. 2007.

- Guidelines on infant oral health care. Ped Dent. 2008; 30:90-93.

- Kohler B, Andreen I, Jonsson B, Hultqvist E. Effect of caries preventive measures on streptococcus mutans and lactobacilli in selected mothers. Scand J Dent Res. 1982;90:102-108.

- Caufield PW, Cutter GR, Dasanayake AP. Initial acquisition of mutans streptococci by infants: evidence for a discrete window of infectivity. J Dent Res. 1993;72:37-45.

- Berkowitz RJ. Mutans streptococci: acquisition and transmission. Ped Dent. 2006; 28:106-109.

- Davey AL, Rogers AH. Multiple types of the bacterium streptococcus mutans in the human mouth and their intra-family transmission. Arch Oral Biol. 1984;29:453-460.

- Berkowitz RJ, Jones P. Mouth to mouth transmission of the bacterium streptococcus mutans between mother and child. Arch Oral Biol. 1985;30:377-379.

- Douglass JM, Tinanoff N, Tang JM, Altman DS. Dental caries patterns and oral health behaviors in Arizona infants and toddlers. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2001;29:14-22.

- Kaste LM, Drury TF, Horowitz AM, Beltran E. An evaluation of NHANES III estimates of early child – hood caries. J Public Health Dent. 1999;59:198-200.

- Drury TF, Horowitz AM, Ismail AI, et al. Diagnosing and reporting early childhood caries for research purposes. J Public Health Dent. 1999;59:192-197.

- Reisine S, Douglass JM. Psychosocial and behavioral issues in early childhood caries. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1998; 26(suppl):32-44.

- Davies GN. Early childhood caries: A synopsis. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1998; 26(suppl): 106-116.

- Seow WK. Biological mechanisms of early childhood caries. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1998;26(suppl):8-27.

- Li Y, Caufield PW. The fidelity of initial acquisition of mutans streptococci by infants from their mothers. J Dent Res. 1995; 74(2):681-685.

- Kohler B, Bratthal D, Krasse B. Preventive measures in mothers influence the establishment of the bacterium streptococcus mutans in their infants. Arch Oral Biol. 1983; 28:225-231.

- Acs G, Lodolini G, Kaminshy S, Cisneros GJ. Effect of nursing caries on body weight in pediatric populations. Ped Dent. 1992; 14:302-305.

- Clarke M, Locker D, Berall G, Pencharz P, Kenny DJ, Judd P. Malnourishment in a population of young children with severe early childhood caries. Ped Dent. 2006;28:254-259.

- Ismail AI. Prevention of early childhood caries. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1998; 26(suppl):49-61.

- Kohler B, Andreen I, Jonsson B. The effects of caries—preventive measures in mothers on dental caries and the oral presence of the bacteria streptococcus mutans and lactobacilli in their children. Arch Oral Biol. 1984;29:879-883.

- Brambilla E, Felloni A, Gagliani M, Malerba A, Garcia-Goday F, Strohmenger L. Caries prevention during pregnancy: results of a 30-month study. J Am Dent Assoc. 1998;129:871-877.

- Isokangas P, Soderling E, Pienihakkinen K, Alanen P. Occurrence of dental decay in children after maternal consumption of xylitol chewing gum, a follow-up from 0 to 5 years of age. J Dent Res. 2000;79:1885-1889.

- Lopez NJ, Smith PC, Gutierrez J. Periodontal therapy may reduce the risk of preterm low birth weight in women with periodontal disease: a randomized controlled trial. J Perio. 2002; 73:911-924.

- Jeffcoat MK, Hauth JC, Geurs NC, et al. Periodontal disease and preterm birth: results of a pilot intervention study. J Perio. 2003;74:1214-1218.

- Erickson PR, Mazhari E. Investigation of the role of human breast milk in caries development. Ped Dent. 1992;21:86-90.

- Tinanoff N. Introduction to early childhood caries conference: initial description and current understanding. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1998;26(suppl):5-7.

- Guideline on fluoride therapy. Ped Dent. 2007; 29(suppl):111-114.

- Fluoride supplementation for children: interim policy recommendations. Pediatrics. 1995;95:777.

- Adair SM. Evidence-based use of fluoride in contemporary pediatric dental practice. Ped Dent. 2006;28:133-142.

- ten Cate JM. Review on fluoride, with special emphasis on calcium fluoride mechanisms in caries prevention. Eur J Oral Sci. 1997;105:461-465.

- Engel-Brill N, Gedalia I, Raxn F, Friedwald E, Rot – mann M, Rosen L. The effect of topical fluoride agents on saliva secretion. J Oral Rehab. 1996;23:501-504.

- Kuthy RA, McTigue DJ. Fluoride prescription practices of Ohio physicians. J Public Health Dent. 1987;47:172-176.

- Levy SM, Muchow G. Provider compliance with recommended dietary fluoride supplement protocol. Am J Public Health. 1992;82:281-283.

- Kohler B, Bratthall D. Intrafamilial levels of strep – tococcus mutans and some aspects of the bacterial transmission. Scand J Dent Res. 1978;86:35-42.

- Klein H. The family and dental disease IV. Dental disease (DMF) experience in parents and offspring. J Am Dent Assoc. 1946;33:735.

- Wan A, Seow W, Purdie D, Bird P, Walsh L, Tudehope D. A longitudinal study of streptococcus mutans colonization in infants after tooth eruption. J Dent Res. 2003;82:504-508.

- Hale KJ. Oral health risk assessment timing and establishment of the dental home. Pediatrics. 2003;111:1113-1116.

- Oral health policies. Ped Dent. 1999;21:18-37.

- Seow WK, Humphrys C, Tudehope DI. Increased prevalence of developmental dental defects in lowbirthweight children: a controlled study. Ped Dent. 1987;9:221-225.

- The use and misuse of fruit juice in pediatrics. Pediatrics. 2001;107:1210-1213.

- Nowak AJ, Casamassimo PS. The dental home: a primary oral health concept. J Am Dent Assoc. 2002; 133:93-98.

- Oral health risk assessment timing and estab – lishment of the dental home. Pediatrics. 2003; 111: 1113-1116.

- Nowak AJ. Rationale for the timing of the first oral evaluation. Ped Dent. 1997;19:8-11.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. May 2009; 7(5): 34-37.