LIGHTFIELDSTUDIOS/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

LIGHTFIELDSTUDIOS/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

Smokeless Doesn’t Equal Safe

Oral health professionals need to be well versed in the adverse effects of e-cigarettes so they can effectively educate their patients.

This course was published in the April 2019 issue and expires April 2022. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Define the mechanism of action and ingredients of e-cigarettes.

- Identify the prevalence of e-cigarette use.

- Discuss the risks and side effects of e-cigarette use.

- Explain the role of the oral health professional in educating patients regarding e-cigarette use.

Smoking has taken on a new form. While the use of traditional cigarettes has declined, alternatives, such as electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) or vaping, have been gaining popularity.1,2 Middle and high school students are the largest users of these smoking alternatives.1,2 According to a report by the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2.1 million US middle and high school students used e-cigarettes in 2017.1 This new fad can have deleterious health consequences. E-cigarettes contain varying levels of nicotine and other chemicals known to increase the risk of cancer.2 In addition, e-cigarettes can harm the oral cavity. Oral health professionals need to educate patients about the potential harm of these products.

E-cigarettes are electronic devices developed as a nicotine delivery alternative to traditional (combustible) cigarettes. Initially, they were designed to help addicted smokers quit the habit.3 The first patent for e-cigarettes was issued in 1965. In 2005, Hon Lik created and patented an e-cigarette that contained nicotine without the tar.3 However, neither the World Health Organization nor the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) supports the use of e-cigarettes as approved smoking cession tools.

E-cigarettes have experienced a significant gain in popularity as an alternative to traditional cigarette smoking, even among nonsmokers, and the industry has seen increasing sales.4,5 Today, e-cigarettes are available in convenience stories and smoke and vape shops across the country.

MECHANICS

The first generation of e-cigarettes resembled traditional cigarettes and were fully disposable.4 The newer generations have refillable and replaceable parts (Figure 1). An e-cigarette is composed of three main parts: battery, atomizer, and a liquid, which often contains nicotine.

The lithium battery is rechargeable using a USB port. The atomizer contains a wick and a metal coil. When a puff is taken, the coil is heated to approximately 400° F via the battery, and the liquid is aerosolized.6 The aerosolized liquid appears as a vapor when exhaled that resembles smoke. Other larger nicotine delivery systems, such as mods or tank systems, are available and bear no resemblance to traditional cigarettes.

INGREDIENTS

Although the liquid in e-cigarettes does not contain combustible tobacco,7 it usually contains nicotine, which is derived from the tobacco plant. Nicotine can also be manufactured synthetically.8 Many types of liquids are available.3,5 Most liquids contain propylene glycol, vegetable glycerin, nicotine, and flavorings, such as menthol, bubblegum, and strawberry.5,9 Carcinogens, such as formaldehyde, acetaldehyde, and nitrosamine, have been found in e-cigarette vapor.10 Additionally, trace amounts of lead and calcium have been found in the liquid due to the heating mechanism, as well as diacetyl.11,12 Diacetyl is a chemical that provides the creamy, buttery flavor used in microwave popcorn; however, it destroys the lungs’ airways, which can lead to bronchiolitis obliterans, or popcorn lung.12

Besides flavorings and nicotine, e-liquids can contain cannabis.13 In a 2015 study of high school students conducted by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, 65% said they were only vaping flavorings, 20% said they were vaping nicotine, 6% said they were vaping marijuana, and the remaining 6% said they did not know what they were vaping.13

PREVALENCE

The popularity of e-cigarettes continues to grow, especially among adolescents and young people. In a 2017 study, nearly one in three high school seniors reported using e-cigarettes.14 According to the FDA, from 2017 to 2018, e-cigarette use increased 78% among high school students (11.7% to 20.8%) and 48% among middle school students (3.3% to 4.9%).14,15

According to the US Department of Health and Human Services 2016 Executive Survey, e-cigarette use among those younger than 25 has surpassed that of adults older than 25.2 E-cigarettes have been adopted by younger generations because of the flavors, packaging, and ease in obtaining.2,5 Until recently, there were no age restrictions on the sale and distribution of e-cigarettes to minors.16

E-cigarettes are also popular among adults mainly due to the following: role as tobacco cessation aids, perception they are less harmful than traditional cigarettes, ability to avoid creating second-hand smoke, and to circumvent indoor smoking restrictions.17–19 In 2016, roughly 68% of adults who smoked wanted to quit, but only 7.4% succeeded, a testament to how difficult quitting may be for some people.20 However, despite its popularity as a smoking cessation aide, the effectiveness of e-cigarette use as a smoking cessation device has not been established.2

RISKS AND SIDE EFFECTS

E-cigarette use has been associated with throat, eye, and airway irritation.21 E-cigarette use can also constrict airway flow and reduce exhaled nitrous oxide.21 While the overall long-term health consequences of e-cigarette use are unknown, asthma has been reported in children with consistent exposure.21

A 5 ml refillable e-cigarette cartridge can contain a nicotine concentration of 20 mg/mL.21,22 A lethal dose of nicotine is estimated at 10 mg in children and between 30 mg and 60 mg in adults.21,22

Nicotine is highly addictive, and at least one-third of users report being just as addicted to e-cigarettes as they were to cigarettes.23 Nicotine stimulates the brain to release epinephrine and dopamine.16 Dopamine plays a large role in reward-motivated behavior, creating the desire to use nicotine repeatedly.16

Despite the visual lack of secondhand smoke, e-cigarette vapors can still potentially expose people nearby to nicotine and other chemicals.23 Flouris et al24 found that the acute effects of e-cigarettes on lung function were similar to those of tobacco cigarettes. E-cigarette liquid can remain on surfaces for weeks to months, which can lead to third-hand exposure or accidental ingestion by children.25 Furthermore, because nicotine can cross the placenta, the use of any nicotine-containing product can cause adverse effects during or after pregnancy.2

In addition to the systemic health concerns, e-cigarettes can negatively affect the oral cavity. The chemical vapors produced by vaping can alter or damage the epithelial cells, leading to oral ulcerations or oral cancer.26 While additional studies on the effects of e-cigarette vapors are needed, early research has indicated an inflammatory response in periodontal ligament fibroblasts, which may lead to a greater risk for periodontal disease.27,28 Other side effects include sore throat, dry mouth, ulcers, headache, nausea, hoarseness, and coughing.11

DEVICE DANGERS

Mechanical failure has been reported with e-cigarette devices, including spontaneous combustion of the lithium battery.29 Explosions occur when the battery short circuits. This is most often the result of overcharging, overheating, moisture exposure, contact with metal objects, faulty batteries, or battery charging with incompatible devices.29 Injuries, such as burns and blast wounds, have been associated with the explosions.30 According to the US National Fire Data Center, there were 195 fire and explosion incidents due to e-cigarettes between January 2009 and December 2016.29 From these malfunctions, 38 resulted in severe injury and hospitalization for a loss of a body part, third degree burns, or facial injuries.29 To date, there are no laws concerning the safety of e-cigarette batteries.29

NEW GUIDELINES

Until recently, there were no definitive guidelines for the sale, distribution, and marketing of e-cigarettes.12 In 2014, the FDA classified e-cigarettes as tobacco products in an effort to provide regulatory guidance and authority over the industry.7 In 2016, e-cigarettes became subject to the same regulations as other tobacco products.12 As such, manufacturers are required to disclose their ingredients and include health warnings on their packaging. The new rule also restricts youth access by prohibiting the sale of e-cigarettes to those younger than 18.30 E-cigarettes contain varying amounts of nicotine, therefore nicotine dependence is a concern. Some vaping products contain nicotine levels higher than a traditional tobacco cigarettes, increasing the likelihood of addiction.2,21,22 Furthermore, there is widespread belief among adolescents and younger adults that vaping is safer than traditional cigarettes.13,21 Appealing candy-like flavorings and marketing to youth are associated with an increase of e-cigarette use among adolescents. Beginning in 2018, all tobacco or tobacco-like products covered by the new FDA regulation must include a nicotine addictiveness warning on all packages and advertisements.14

THE ROLE OF THE ORAL HEALTH PROFESSIONAL

Dental professionals have a responsibility to educate their patients and the public on the detrimental effects of smoking, including the use of e-cigarettes. Medical history forms should include questions on the use of not only traditional tobacco products, but also the use of alternatives. Tobacco cessation programs should include educating patients about the dangers associated with vaping. Furthermore, only approved smoking sessions therapies, such as the patch, gum, or medication, should be recommended as tobacco cessation aids.31

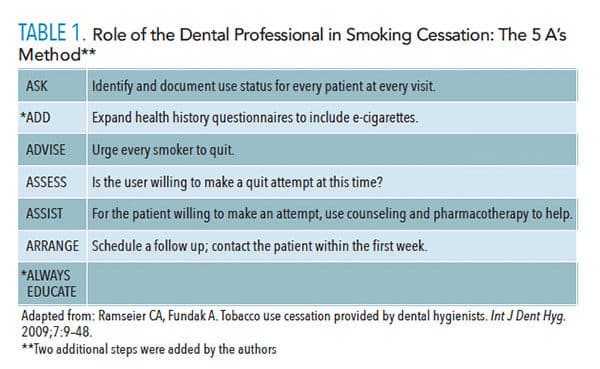

Several health organizations have adopted the 5 A’s as an intervention model based on evidence-based guidelines for smoking cessation.31 The 5 A’s method suggests the health care professional follow these steps: Ask, Advise, Assist, and Arrange. Table 1 provides an overview of the 5 A’s. We have added two steps: Add and Always Educate.

Many health history forms only include questions about traditional cigarettes, such as “Do you smoke?” Newer health history forms should include or “Add” questions relating to all smoking-related habits, such as “Do you use e-cigarettes, vapes, or hookahs?” Oral health professionals should take the time to “Always Educate” parents and caregivers about the effects of e-cigarettes.

When addressing patients who smoke, whether with traditional cigarettes or alternatives, a nonoffensive, nonthreatening, and nonconfrontational manner should be used.

Motivational interviewing (MI) is a way to help counsel patients to quit smoking. According to Ramseier and Fundak,31 the purpose of MI is to gauge the patient’s motivation to change, increase the patient’s desire and confidence to change, and gain the patient’s commitment to discuss the change at a follow up visit or call. For those patients who continue to struggle, or who have experienced a relapse, the health care professional should make a referral to the patient’s primary care provider.

![]() CONCLUSION

CONCLUSION

E-cigarettes are marketed as a less harmful alternative to cigarettes, however they are not without side effects. Vaping is on the rise, especially among young and impressionable populations. The long-term effects of e-cigarettes are unknown and more research is needed. Furthermore, vaping has not been identified as a proven smoking cession tool. Therefore, clinicians must educate the public on the potential harm of e-cigarettes and other nicotine delivery systems and recommend only evidence-based smoking cessation options.

REFERENCES

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Electronic Cigarettes. Available at: cdc.gov/ tobacco/ basic_ information/ e-cigarettes/ index.htm. Accessed March 21, 2019.

- United States Department of Health and Human Services. E-Cigarette Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General Executive Summary. Available at: https:/ / e-cigarettes.surgeongeneral.gov/ documents/ 2016_ SGR_ Exec_ Summ_ 508.pdf. Accessed March 21, 2019.

- Zhu S-H, Sun JY, Bonnevie E, et al. Four hundred and sixty brands of e-cigarettes and counting: implications for product regulation. Tob Control. 2014;23Suppl 3:iii3–iii9.

- Palazzolo DL. Electronic cigarettes and vaping: a new challenge in clinical medicine and public health: A literature review. Front Public Health. 2013;56:1–20.

- American Dental Association. E-Cigarettes, Research and Your Health: What Do We Know About Electronic Cigarettes? Available at: https:/ / www.adafoundation.org/ ~/ media/ ADA_ Foundation/ Files/ ADA-Foundation-VRC-Vaping-Research-and-Health.pdf?la=en. Accessed March 21, 2019.

- Holliday R, Stubbs CA. Dental Perspective On Electronic Cigarettes: The Good, The Bad and The Ugly. Available at: https:/ / www.oralhealthgroup.com/ features/ a-dental-perspective-on-electronic-cigarettes-the-good-the-bad-and-the-ugly/ . Accessed March 21, 2019.

- Nicotine and Tobacco Research. Are E-Cigarettes Tobacco Products? Available at: https:/ / academic.oup.com/ ntr/ article/ 21/ 3/ 267/ 5041976. Accessed March 21, 2019.

- Felman A. Everything you need to know about nicotine. Available at: medicalnewstoday.com/ articles/ 240820.php. Accessed March 21, 2019.

- Willershausen I, Wolf T, Weyer V, Sader R, Ghanaati S, Willershausen B. Influence of e-smoking liquids on human periodontal ligament fibroblasts. Head Face Med. 2014;10:1–7.

- Goniewicz ML, Knysak J, Gawron M, et al. Levels of selected carcinogens and toxicants in vapour from electronic cigarettes. Tob Control. 2013;23133–139.

- Williams M, Bozhilov K, Ghai S, Talbot P. Elements including metals in the atomizer and aerosol of disposable electronic cigarettes and electronic hookahs. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0175430.

- Sherry JS, Blackstad NM, Wheatley KS. E-cigarettes, vaping and chairside education. Available at: dentalacademyofce.com/ courses/ 3229%2FPDF%2F1612cei_ Sherry-Vaping_ web.pdf. Accessed March 21, 2019.

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. Teens Using E-cig Devices Not Just For Nicotine. Available at: drugabuse.gov/ news-events/ news-releases/ 2016/ 08/ teens-using-e-cig-devices-not-just-nicotine. Accessed March 21, 2019.

- United States Food and Drug Administration. Vaporizers, e-cigarettes, and other electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS). Available at: fda.gov/ TobaccoProducts/ Labeling/ ProductsIngredientsComponents/ ucm456610.htm. Accessed March 21, 2019.

- United States Food and Drug Administration. FDA takes new steps to address epidemic of youth e-cigarette use, including a historic action against more than 1,3000 retailers and 5 major manufacturers for their roles perpetuating youth access. Available at: fda.gov/ NewsEvents/ Newsroom/ PressAnnouncements/ ucm620184.htm. Accessed March 21, 2019.

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. Electronic Cigarettes. Available at: drugabuse.gov/ publications/ drugfacts/ electronic-cigarettes-e-cigarettes#ref. Accessed March 21, 2019

- Watkins SL, Glantz SA, Chaffee BW. Association of noncigarette tobacco product use with future cigarette smoking among youth in the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study, 2013-2015. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172:181–187.

- Etter J, Bullen C. Electronic cigarettes: Users profile, utilization, satisfaction and perceived efficacy. Addiction. 2011;106:2017–2028.

- Cobb CO, Hendricks PS, Eissenberg T. Electronic cigarettes and nicotine dependence: evolving products, evolving problems. BMC Med. 2015;13:119.

- Caraballo, RS, Shafer, PR, Patel, D, Davis, KC, McAfee, TA. Quit methods used by us adults cigarette smokers, 2014-2016. Available at: cdc.gov/ pcd/ issues/ 2017/ 16_ 0600.htm. Accessed March 21, 2019.

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Policy on Electronic Cigarettes. Reference Manual. Available at: aapd.org/ media/ policies_ guidelines/ p_ electroniccig.pdf. Accessed on March 21, 2019.

- Cameron JM, Howell D, White J, Andrenyak D, Layton M, Roll M. Variable and potentially fatal amounts of nicotine in e-cigarettes solutions. Tob Control. 2014;23:77–78.

- Glasser AM, Collins L, Pearson JL, et al. Overview of electronic nicotine delivery systems: A systematic review. Am J Prevent Med. 2017;52:e33–e66.

- Flouris AD, Chorti M, Poulianiti K, Jamourtas A, Kostikas K, Tzatzarakis M. Acute impact of active and passive electronic cigarette smoking on serum cotinine and lung function. Inhalation Toxicol. 2013;25:91–101.

- Harrison R, Hicklin D. Electronic cigarette explosions involving the oral cavity. J Am Den Assoc. 2016;147:891–896.

- Sundar IK, Javed F, Romanos GE, Rahman I. E-cigarettes and flavorings induce inflammatory and pro-senescence responses in oral epithelial cells and periodontal fibroblasts. Oncotarget. 2016;7:77196–77204.

- Tatullo M, Gentile S, Paduano F, Santacroce L. Marrelli M. Crosstalk between oral and general health status in e-smokers. Medicine. 2016;95:1–7.

- National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research. Effects of E-cigarette Aerosol Mixtures On Oral and Periodontal Epithelia. Available at: nidcr.nih.gov/ grantsandfunding/ See_ Funding_ Opportunities_ Sorted_ By/ ConceptClearance/ CurrentCC/ Effects-of-E-cigarette.htm. Accessed March 21, 2019.

- Saxena S, Kong L, Pecht M. Electronic cigarettes: A battery safety issue. Availabel at: https:/ / ieeexplore.ieee.org/ stamp/ stamp.jsp?arnumber=8328814. Accessed March 21, 2019.

- United States Food and Drug Administration. The Facts Of FDA’s New Tobacco Rule. Available at: fda.gov/ ForConsumers/ ConsumerUpdates/ ucm506676.htm. Accessed March 21, 2019

- Ramseier CA, Fundak A. Tobacco use cessation provided by dental hygienists. Int J Dent Hyg. 2009;7:9–48.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. April 2019;17(4):26–29.

I recently did an interview with a Tobacco Cessation expert and was so surprised of how prevalent this was in the young community. This is such a needed article for clinicians today.- Jasmin