Sleep Apnea Screening in the Dental Office

Oral health professionals play a key role in ensuring that patients with this common disorder receive an accurate diagnosis and effective treatment.

This course was published in the January 2014 issue and expires January 2017. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Define sleep apnea and sleep hypopnea.

- Discuss the comorbidities associated with sleep apnea.

- List effective screening protocols for sleep apnea in the dental setting.

- Identify the different methods of treating sleep apnea.

WHAT IS SLEEP APNEA?

Apnea is defined as cessation of air flow into the lungs for at least 10 seconds, while hypopnea is a decrease in airflow that occurs during sleep.4 Almost everyone experiences some type of apnea when sleeping; however, patients with sleep disorders experience long and frequent absences of breathing or decreased quality of breathing, which, in turn, decreases the body’s oxygen saturation to unhealthy levels.4

There are three types of sleep apnea. A patient is diagnosed with?obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) when the episodes of apnea and hypopnea occur more than five times per night and are due to an obstruction of the airway.5 Caused by a partial or full collapse of the upper airway, OSA happens when the muscles become relaxed during sleep.4,5 When the airway muscles relax, the airway is constricted—reducing the airflow into the lungs or blocking the airway, which results in total cessation of air flow even though the body is continually trying to take in air.5 Reduction of airflow resulting from this obstruction may cause the patient to snore; however, all individuals who snore do not have OSA. When an individual experiences five to 15 abnormal respiratory events per hour of sleep, OSA is deemed mild; 15 to 30 abnormal respiratory events per hour of sleep is noted as moderate; and more than 30 abnormal respiratory events per hour of sleep is considered severe OSA.6

Central sleep apnea is another type of sleep apnea. It causes an individual’s oxygen saturation to decrease because the brain fails to send a signal to breathe, which causes apnea or breaths that are very shallow and ineffective. Both OSA and central sleep apnea cause an individual to wake up due to the low levels of oxygen saturation.7 Patients with central sleep apnea may also experience OSA, but until a patient receives an OSA diagnosis, central sleep apnea may go unnoticed.7

Complex sleep apnea is the third type of apnea and occurs when patients exhibit a combination of OSA and central sleep apnea. In a retrospective review of 223 patients, investigators found complex sleep apnea comprised 15% of all patients with sleep apnea.8 When patients experience one or more of the three types of sleep apnea, they have OSA syndrome.6 This article will focus on OSA, the most common type of sleep apnea.

OBSTRUCTIVE SLEEP APNEA COMORBITIES

Comorbidities associated with OSA have common risk factors. Researchers are interested in investigating premature death and disease and the role sleep deprivation plays in chronic illnesses such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, obesity, depression, inflammatory changes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, mortality, and motor vehicle accidents.9–14 Sleep deprivation results in metabolic changes that lead to weight gain.10 Studies show that patients who have difficulty falling asleep and experience reduced sleep quality have a higher incidence of prediabetes and, in the presence of type 2 diabetes, poor A1c control.13 This is because OSA may increase insulin resistance through sympathetic nerve activity.13 Treating sleep disorders in patients with type 2 diabetes may improve glycemic control.13

Studies suggest that OSA may also be an important predictor in cardiovascular disease and an independent risk factor among patients with cardiovascular disease.14–20 Patients with untreated OSA show an increased rate of systemic hypertension, when compared to healthy patients who exhibit only snoring at night. Other clinical consequences of OSA are pulmonary hypertension due to resting increase of pulmonary artery pressure. The link between OSA and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is less clear, but relevant in the fact that oxygen saturation is lower among patients who have both diseases.12

Patients with ischemic heart disease and coronary artery disease are at an increased risk of myocardial infarction when oxygen saturation is at its lowest during episodes of apnea. Golbin et al14 found that approximately 75% of atrial fibrillation onsets occurred between the hours of 8 pm and 8 am when continuous cardiac monitoring was conducted with an atrial defibrillator. Patients with OSA are also vulnerable to cardiac arrhythmias. Flemons et al16 discovered the presence of bradycardia arrhythmias during apneas and hypopneas, suggesting that patients with severe apnea have an increased risk of cardiac arrhythmias. OSA may raise the risk of cerebrovascular disease by decreasing the oxygenated blood flow during periods of apneas.15 Areas of the brain with low cerebral vascular reactivity are at an increased incidence for stroke.17 The inflammation process and central obesity play a large role in the cardiovascular disease process, which is exacerbated by OSA.20 The most common psychological concerns found in patients with OSA are depression and anxiety.21

OSA is also directly related to excessive daytime fatigue. In 2008, Vanlaar et al22 found that 58% (750 participants) of drivers in Ontario, Canada, admitted to driving while fatigued or drowsy. Excessive daytime fatigue and sleepiness increase the risk of driving accidents.22,23 These findings raise the question of whether routine screening for OSA should be performed on all patients.

SCREENING FOR OSA IN THE DENTAL OFFICE

One of the greatest obstacles in implementing OSA screening in the dental office is teaching the team to create conversations with patients about sleep apnea and its symptoms. Most patients are unaware they have a sleep disorder.

Once the dental team is trained, the actual screening process is simple and can be completed in a few minutes. The dentist leads the dental team in establishing OSA screening as an expectation, and provides training on the revised medical history, physical examination, and communication to discuss potential sleep issues. Dental hygienists can play a critical role in sustaining this paradigm shift through effective communication with the patient, review of the medical history, and knowledge of the oral cavity.

The dental hygienist begins with a thorough analysis of the medical history, which includes recording gender; smoking and alcohol use; and the presence of hypertension, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and menopause. Medical histories that help screen for OSA include questions regarding symptoms, such as grinding at night, morning headaches, being overweight, problems sleeping, family history of OSA, sleeping in a supine position, inability to concentrate, feeling irritable or depressed, waking up frequently at night with a dry or sore throat, neck circumference greater than 17 inches, and nighttime nasal congestion.24–26 If the patient notes alcohol consumption on the medical history, the dental hygienist should follow up with questions about frequency and if ingestion occurs before bedtime.24–26 Including a patient’s spouse, who may be more aware of the patient’s nighttime symptoms, such as loud snoring or gasping for breath during sleep, may be appropriate.

The dental hygienist’s ability to recognize the signs of sleep apnea is paramount. Oral manifestations of OSA may be interpreted by the dental professional as common anomalies, hence a review is important. Patients with OSA may present with a large tongue, long soft palate, enlarged uvula, broad tonsillar pillars, tonsillar tissue, redundant pharyngeal tissue, linea alba, scalloped tongue (Figure 1), erosion, wear on the lower incisors (Figure 2), and vaulted palate. By bringing these oral signs of OSA to the patient’s attention, the dental hygienist may be able to elicit more information about his or her risk of sleep disorders.

Bruxism, a wearing of the lower incisors, may be related to the forward thrusting of the jaw while sleeping in an effort to force the airway open from the obstruction caused by the tongue.24 Bruxism is often treated with a nightguard, and the possibility that sleep apnea is a causative factor may be overlooked. Additionally, acid erosion of teeth due to gastroesophageal reflux disease may be related to sleep apnea, but this possibility is often missed by health care professionals. While the airway is obstructed, the respiratory and abdominal muscles react to the dropping oxygen levels by causing a reflux of acid into the oral cavity. During the time the airway is obstructed, the respiratory and abdominal muscles react to the dropping oxygen levels by causing a reflux of acid into the oral cavity.24

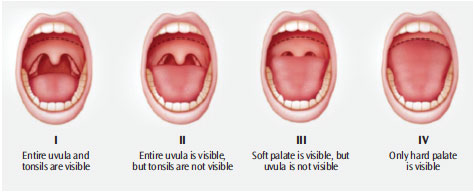

The tongue’s position and shape can provide information in the screening process for sleep apnea. Tongue scalloping, which refers to indentations on the edge of the tongue, is associated with the diagnosis of sleep disorders.27 The Friedman Tongue Classification System—commonly used in dentistry—evaluates the tongue’s position in the mouth and assigns a value to each position based on how much of the tongue obstructs the airway (Figure 3). The dental hygienist can document the classification in the progress note using the Friedman Tongue Classification grades I through IV.25 If the tongue is the primary cause of the obstruction and other methods of treatment have not been successful, oral appliances are the most effective in treating mild to moderate sleep apnea.28 A large tongue that visually blocks the airway while in a neutral position is an indication of more severe OSA.

SCREENING QUESTIONNAIRES

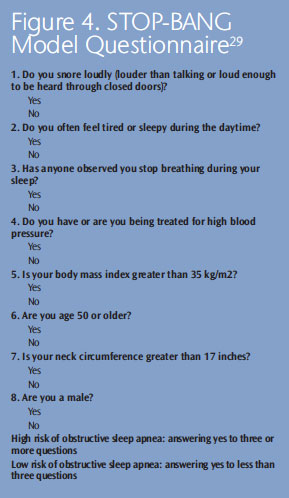

Questionnaires to assess for sleep apnea are available for use in the dental office. The STOP-BANG Sleep Apnea Screening Tool (Figure 4)29 and Epworth Sleepiness Scale30 have a high degree of validity. The STOP-BANG is used as a risk assessment indicator for sleep apnea.31 The acronym STOP represents (S) Do you snore loudly? (T) Are you tired during the day (daytime fatigue)? (O) Has anyone observed you stop breathing while sleeping? and (P) Do you have high blood pressure? If a patient answers yes to three out of the four questions, the practitioner continues onto the BANG portion of the questionnaire. The BANG questions include (1) Is your BMI greater than 35 kg/m2? (2) Are you age 50 or older? (3) Is your neck circumference greater than 17 inches? and (4) Are you male?27 If any of these questions result in positive answers, the dental hygienist reports the findings to the dentist, who then refers the patient to a physician specializing in sleep disorders.29

Results from the Epworth Sleepiness Scale are often requested by insurance companies when validating the need for treatment. The Epworth Sleepiness Scale measures the daytime sleepiness through a short questionnaire.30 The patient is asked to rate the incidence of falling asleep during different activities, such as while sitting, reading, or watching television; while riding in or driving a car; while having a conversation; and after eating, as well as disclose whether he or she takes an afternoon nap.30 The scale provides an ordinal ranking with 0 to 9 being normal and 10 to 24 indicating the need for consultation with a sleep physician.28

POST-SCREENING

After a positive screen for sleep apnea is established, the dentist refers the patient to a sleep specialist for final diagnosis. Sleep apnea touches many specialties within the medical community, including pulmonary medicine, neurology, otolaryngology, and psychiatry.7 A careful diagnosis must be made by a physician through a sleep study, which can be conducted at home or in a sleep laboratory.

During a laboratory-based sleep study, a polysomnogram is used to assess oxygen saturation, heart rate and rhythm, nasal pressure transduction, and oral air flow.6 Sleep stage is measured with electroencephalography, and jaw muscle tone is evaluated by electromyography. Sleep position, along with chest and abdominal movement, are also monitored.9 Polysomnography, when conducted by trained professionals, provides the technology to study and record the characteristics of sleep. More recently, the use of at-home sleep studies has been introduced because of the prevalence of OSA and the often lengthy wait list for polysomnography in a sleep medicine laboratory. All of these measurements must be analyzed by a physician to determine the type and severity of sleep disordered breathing.6

TREATMENT OPTIONS

Continuous positive air pressure (CPAP) is the gold standard for treatment of sleep apnea.9 A CPAP machine opens the airway by increasing air pressure and displacing the tissues in the pharynx, thus reducing obstruction. Unfortunately, compliance with CPAP treatment is often unpredictable; patients do not like wearing bulky masks and frequently complain of dry airways and nosebleeds.9 Depending on where the obstruction takes place, surgery may be a viable option. One size does not fit all when treating patients with sleep apnea.

An oral appliance is often used to treat mild to moderate sleep apnea or when a patient is unable to tolerate the CPAP machine.31–35 If an oral appliance is recommended for the treatment of OSA, a sleep study with a polysomnogram to test effectiveness of the oral appliance is necessary. The efficacy of oral appliance therapy compared to CPAP is controversial. A 2-year follow-up study comparing the two methods showed no significant difference for mild to moderate sleep apnea.32 The purpose of an oral appliance is to advance the mandible to keep the tongue from obstructing the airway.33 The advancement must be within a range of the patient’s mandibular motion that does not cause temporomandibular joint pain or myofacial pain or dysfunction.34 Documentation of assessment prior to placement of the oral appliance is important. A titration of the mandible’s advancement is performed over time until a position is established that eliminates the obstruction. It is important to use an appliance that is approved for use by the US Food and Drug Administration and allows for adjustments within a patient’s range of motion.5,35 After the appliance is delivered, polysomnography and a patient and/or partner interview should be conducted to determine efficacy. Careful monitoring and follow-up are important as health conditions may change that require further evaluation by a sleep physician.

CONCLUSION

An interdisciplinary approach is the most effective when diagnosing and treating sleep apnea. The dental team may lead the process by screening for OSA and making an appropriate referral to a physician for diagnosis and treatment options. The dental hygienist should ask if the patient has followed through with the referral to a sleep specialist. If so, treatment progress should be discussed.

Dental hygienists play a key role in evaluating the use of the therapeutic devices used in OSA treatment. Dental professionals, working as a team with the physician, can provide reinforcement of the selected treatment, intervention if the recommended treatment is not utilized by the patient, and offer appropriate follow up.

Because most patients are not aware they have a sleep disorder, dental hygienists can have a tremendous impact on successful outcomes for patients with OSA. Dental hygienists excel at the communication and motivational skills necessary to implement screening and supportive interactions into practice. The key to successful outcomes is through early screening, detection, and referral for diagnosis and treatment of OSA.

REFERENCES

- A.D.A.M. Medical Encyclopedia. Sleep Disorders Overview. Available at: ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMH0001803. Accessed January 1, 2014.

- American Sleep Apnea Association. Enhancing the Lives of Those with Sleep Apnea. Available at: sleepapnea.org/i-am-a-health-care-professional. html. Accessed January 1, 2014.

- Smith R, Ronald J, Delvaive K, Walld R, Manfreda J, Kryger MH. What are obstructive sleep apnea patients being treated for prior to this diagnosis. Chest. 2002;121:164–172.

- A.D.A.M. Medical Encyclopedia. Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Available at: ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMH0001814. Accessed January 1, 2014.

- Qureshi A, Ballard RD, Nelson HS. Obstructive sleep apnea. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;112: 643–651.

- McNicholas W. Diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea in adults. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;27:154–160.

- American Sleep Apnea Association. Central Sleep Apnea. Available at: sleepapnea.org/learn/ sleep-apnea/central-sleep-apnea.html. Accessed January 1, 2014.

- Science Daily. Mayo Clinic Discovers New Type Of Sleep Apnea. Available at: sciencedaily.com/ releases/2006/09/060901161349.htm. Accessed January 1, 2014.

- Lattimore J. Celermajer D. Wilcox I. Obstructive sleep apnea and cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:1429–1437.

- National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. Who Is at Risk for Sleep Apnea? Available at: nhlbi. nih.gov/health/healthtopics/topics/sleepapnea/atrisk.html. Accessed January 1, 2014.

- Young T, Skatrud J, Peppard P. Risk factors for obstructive sleep apnea in adults. JAMA. 2004; 291:2013–2016.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sleep and Chronic Diseases. Available at: cdc.gov/sleep/about_sleep/chronic_disease.htm. Accessed January 1, 2014.

- Yi-Chen T, Kann N, Tung T, et al. Impact of subjective sleep quality on glycemic control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Family Practice. 2011;29:30–35.

- Golbin J. Somers, VK. Caples S. Obstructive sleep apnea, cardiovascular disease and pulmonary hypertension. Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5: 200–206.

- Mitchell AR, Spurrell PA, Sulke N. Circadian variation of arrhythmia onset patterns in patients with persistent atrial fibrillation. Am Heart J. 2003;146:902–907.

- Flemons WW, Remmers JE, Gillis AM. Sleep apnea and cardiac arrhythmias: Is there a relationship? Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;148:618–621.

- Hersi A. Obstructive sleep apnea and cardiac arrhythmias. Ann Thorac Med. 2010;5:10–17.

- Caballero P, Navarro R, Martin O, Martin T. Cerebral hemodynamic changes in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome after continuous positive airway pressure treatment. Sleep Breath. 2013;17: 1103–1108.

- Uma S, Yezhuvath K, Lewis-Amezcua R, Varghese G, Hanzhang L. On the assessment of cerebrovascular reactivity using hypercapnia bold mri. NMR Biomed. 2009;22:779–786.

- McNicholas WT. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and obstructive sleep apnea: overlaps in pathophysiology, systemic inflammation, and cardiovascular disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:692–700.

- Asghari A, Mohammadi F, Kamrava S, Tavakoli S, Farhadi M. Severity of depression and anxiety in obstructive sleep apnea. Eu Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2012;269:2549–2553.

- Vanlaar W, Simpson H, Mayhew D, Robertson R. Fatigued and drowsy driving: a survey of attitudes, opinions and behaviors. J Safety Res. 2008;39:303–309.

- Smolensky MH, Di Milia L, Ohayon MM, Philip P. Sleep disorders, medical conditions, and road accident risk. Accid Anal Prev. 2011;43:533–548.

- Science Daily. Teeth Grinding Linked To Sleep Apnea; Bruxism Prevalent In Caucasians With Sleep Disorders. Available at: sciencedaily.com/releases/ 2009/ 11/091102171213.htm. Accessed January 1, 2014.

- Friedman M, Hamilton C, Samuelson C, Lundgren M, Pott T. Diagnostic value of the Friedman Tongue Position and Mallampati Classification for obstructive sleep apnea: a meta-analysis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;148:540–547.

- Friedman M. Clinical staging for sleep disordered breathing. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;127:13–21.

- Weiss TM, Atanasov S, Calhoun KH. The association of tongue scalloping with OSA. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;133:966–971.

- Almeida FR. Long-term effectiveness or oral appliance versus CPAP therapy and the emerging importance of understanding patient preferences. Sleep. 2013; 36:1271–1272.

- Farney RJ, Walker BS, Farney RM, Snow GL, Walker JM. The STOP-Bang equivalent model and prediction of severity of obstructive sleep apnea: relation to polysomnographic measurements of the apnea/hypopnea index. J Clin Sleep Med. 2011;7:459–465.

- Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep. 1991;14:540–545.

- Coté GA, Hovis CE, Hovis RM, et al. A screening instrument for sleep apnea predicts airway maneuvers in patients undergoing advanced endoscopic procedures. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:660–665.

- Duff M, Hoekema J, Wijkstra P, et al. Oral appliances versus continuous positive airway pressure in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: a 2 year follow up. Sleep. 2013;36:1289–1296.

- Gotsopoulos H, Chen C, Qian J, Cistulli PA. Oral appliance therapy improves symptoms in obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Resp Crit Care Med. 2002;166:743–748.

- Andrew S, Chan L, Lee RWW, Cistulli PA. Non–positive airway pressure modalities. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5:179–184.

- Sunitha C, Kumar SA. Obstructive sleep apnea and its management. Indian J Dent Res. 2010;21:119–124.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. January 2014;12(1):42–46.