Skip the Sugary Drinks

Consuming sugar-sweetened beverages causes a multitude of oral and systemic health problems.

This course was published in the May 2015 issue and expires May 31, 2018. The author has no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Define sugar-sweetened beverages.

- Discuss how the consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages harms the dentition.

- Identify the systemic health concerns associated with consuming sugary drinks.

- Describe the role of the dental hygienist in reducing the consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages.

A sugar-sweetened beverage is defined as any drink with added sugar or sweetener, including soda, punch, fruit juice, lemonade, powdered drinks, sport drinks, and energy drinks.1–5 In 2010, there was an average of 61 nationally-distributed brands of sugar-sweetened beverages with 644 products that were manufactured by 14 different companies.4

The United States population consumes high numbers of sugary drinks, especially young people. On an average day, 80% of children and teenagers consume at least one sugar-sweetened beverage.1–5 Studies show that Americans drink 42 gallons of sugary drinks a year5 and manufacturers reap more than $29 billion annually from the consumption of these products.4

The amount of sugar contained in drinks varies. For example, a 12-ounce soda contains about 45 grams of sugar and a 20-ounce soda contains 75 grams of sugar. Four grams of sugar equals 1 teaspoon, and 1 gram of sugar equals four calories.4 Thus, a 12-ounce soda contains a bit more than 11 teaspoons of sugar while a 20-ounce soda includes more than 18 teaspoons of sugar.3

Regular sodas contain the largest quantity of sugar per beverage.4 The primary ingredient found in energy drinks is caffeine, but sugar is a close second.4 Sports drinks contain less sugar than most sweetened beverages, but one 8-ounce drink still contains 14 grams.4 Sugar-sweetened beverages contain other ingredients, including water, protein, fat, sodium, caffeine, acids, and artificial sweeteners.4 Because these drinks offer little, if any, nutritional benefits, they are often described as containing empty calories.

DESTROYING DENTITION

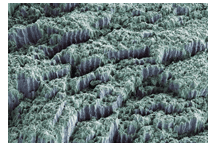

Enamel is one of the hardest materials in the human body (Figure 1); however, it is susceptible to irreversible damage. Research shows that sugar-sweetened beverages can harm the dentition in several ways.6–8 A common misconception is that the high concentration of sugar in these drinks is solely responsible for dental caries, but new research shows that the acidic ingredients play a role in tooth decay, as well.6–8 In addition to dental caries, demineralization, dentinal hypersensitivity, and erosion, which all begin in the same manner, are linked to frequent consumption of sugary drinks.6,8,9

Bacteria that naturally occur in the oral cavity, such as Streptococcus mutans, Lactobacillus, and Actinomyces viscosus, cause the demineralization of tooth enamel. The bacteria colonize on tooth surfaces and feed off the high amount of fermentable carbohydrates in sugar-sweetened beverages (Figure 2).6,7,9 The process of the bacteria metabolizing the sugars causes a decrease in pH levels within the oral cavity and begins the process of enamel demineralization. During demineralization, calcium and phosphorous are stripped from the dental enamel.6,9 In order for demineralization of enamel surfaces to occur, the pH level needs to be between 4.5 and 5.5. On root surfaces, the pH level needs to range from 6.0 to 6.7 in order for demineralization to begin.10 If pH levels remain low for long periods or for repeated exposures, the risk of developing a caries lesion is significantly increased.6,9 Sugar-sweetened drinks contain different types of acid, including carbonic, phosphoric, citric, malic, and tartaric acids.6 The acids in these beverages cause a decrease in pH in the oral cavity, which, in concert with the exposure to fermentable carbohydrates, further demineralizes the enamel. These acids do not need sucrose to start the demineralization process, which may be confusing to patients. They may not understand how “diet” or “light” beverages can still cause dental caries.4 The levels of acid in some beverages is as corrosive as the acid found in car batteries.11

In addition to caries and demineralization, hypersensitivity can be caused by frequent consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages.6 Hypersensitivity can occur when the acids remove the dentin, opening tubules and causing the dentition to become increasingly more aware of stimuli. Drinking sugary beverages also raises the risk of erosion. Because the dentition loses key minerals during demineralization, the weakened enamel may also experience erosion due to opposing occlusal forces during bruxism, hard bristle toothbrushes, or the use of too much force or pressure while toothbrushing.6,9

SYSTEMIC HEALTH CONCERNS

Consuming sugar-sweetened beverages also causes systemic health problems. An estimated 93 million Americans are obese and approximately 9 million adolescents are considered overweight or obese.5 The average American drinks almost 100 pounds of sugar annually.5 When children drink one sugar-sweetened beverage per day, they increase their risk of becoming overweight or obese by 60%.5 Adults who drink one sugary drink per day increase their risk of becoming overweight or obese by 27%.5 Individuals often don’t think of the sugar they’re consuming in beverages and fail to incorporate the calories into their daily intake.12

In the past, research was used to simply recognize the link between dental caries and obesity when consuming excessive amounts of sugar-sweetened beverages; however, scientists are discovering that there are far more health concerns related to sugar consumption, including raising the risk for diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular diseases, liver cirrhosis, and dementia.2,12–19 In addition, obesity is linked to other health disorders, including sleep apnea; cardiovascular disease; respiratory problems; osteoarthritis; gynecological problems; and endometrial, breast, and colon cancer.13–16 When sugar enters the body in a liquid form, it is absorbed and metabolized very quickly, which causes blood sugar to spike.17 Research shows liquid sugar is metabolized in less than 30 minutes; whereas a candy bar, also containing high amounts of sugar, takes longer.17 Frequent spikes in blood sugar cause the body to deposit fat into the liver, which is a direct cause of diabetes. When individuals drink one sugar-sweetened beverage per day, they have increased their risk of developing type 2 diabetes by 26%.18

The prevalence of diabetes has tripled over the past 30 years, while consumption of sugary drinks has doubled.19 Diabetes can cause blindness, amputations, kidney failure, liver disease, cardiovascular complications, cancer, strokes, and even death.20 The sugar contained in most sweetened beverages is far more than is recommended by the American Heart Association (AHA), and excessive sugar consumption can lead to hypertension and obesity.13–15 The AHA recommends children consume only 3 teaspoons of added sugar, about 50 calories, a day.13 Adult women should consume no more than 100 calories, or 6 teaspoons, of added sugar a day, while adult men should consume no more than 150 calories, or 9 teaspoons, of sugar a day.15

RISING SALES

The increase in consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages did not happen overnight, and strategic marketing has played a role.4,5,13,21 Indefatigable marketing ads, increased portion sizes, constant availability, and low cost have fueled the ever-growing popularity of sugary drinks.21 In 2012, the manufacturers of sugary drinks spent $948 million on advertising, whereas products that did not contain sugar spent only $504 million.4 These advertisements are often shown more frequently on television channels that cater to adolescents and children.13 In addition, marketing for sugary drinks frequently uses celebrities who are popular among young people to promote their products.21

Serving sizes for drinks at restaurants have also grown.4,13,21 In the 1950s, sugary drinks came in 6-ounce servings. Today, most servings in fast-food restaurants come in 32-ounce cups, and some stores sell cups that can hold up to 64 ounces.21 Free refills are also commonly provided, so people may actually consume several servings in one sitting. Sugary drinks are also relatively inexpensive and coupons and special sales are frequently offered to encourage customers to buy more. Sugar-sweetened beverages are ubiquitous; they are sold everywhere from grocery stories to office supply warehouses to gyms, schools, and parks.

DENTAL HYGIENISTS CAN HELP

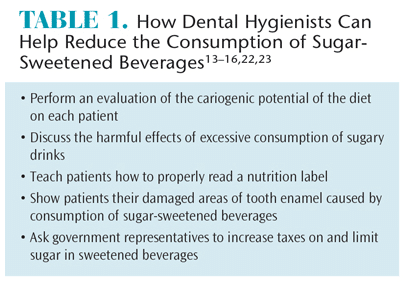

Dental hygienists have a role to play in reducing their patients’ consumption of sugary drinks (Table 1). First, they can help patients to recognize how much sugar they are drinking on a daily basis by asking patients to identify which of their favorite beverages increase their risk for caries. Patients should write down what they consumed over a 3-day, 5-day, or 7-day period. The evaluation should include the type and amount of all food/drinks consumed, how they were prepared, and the time of day they were consumed. At the next appointment, the dental hygienist can identify the sugar ingested as liquid sugar, solid and sticky sugar, or slowly dissolving sugars. The frequency with which each sugar is ingested is tallied and multiplied by one, two, or three, depending on the source. Liquid sugars are multiplied by one, solid and sticky sugars are multiplied by two, and slowly dissolving sugars are multiplied by three. A dietary caries risk score of nine or more indicates that the patient is in need of nutrition counseling to reduce the risk of cariogenic potential in the diet.22

Dental hygienists have a role to play in reducing their patients’ consumption of sugary drinks (Table 1). First, they can help patients to recognize how much sugar they are drinking on a daily basis by asking patients to identify which of their favorite beverages increase their risk for caries. Patients should write down what they consumed over a 3-day, 5-day, or 7-day period. The evaluation should include the type and amount of all food/drinks consumed, how they were prepared, and the time of day they were consumed. At the next appointment, the dental hygienist can identify the sugar ingested as liquid sugar, solid and sticky sugar, or slowly dissolving sugars. The frequency with which each sugar is ingested is tallied and multiplied by one, two, or three, depending on the source. Liquid sugars are multiplied by one, solid and sticky sugars are multiplied by two, and slowly dissolving sugars are multiplied by three. A dietary caries risk score of nine or more indicates that the patient is in need of nutrition counseling to reduce the risk of cariogenic potential in the diet.22

Dental hygienists need to keep in mind that some patients’ caloric intake choices may be related to their cultural or religious background, and these choices should be respected.22 Patients experiencing nutrition-related disease or deficiencies, eating disorders, weight management problems, and metabolic disease need to be referred to a physician or nutritionist and should not be counseled by dental hygienists.22

In addition to assisting them in becoming more aware of their daily consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages, dental hygienists can help patients better understand nutrition labels. They can teach patients about serving sizes and selective wording that may be found on the beverage container that might cause the consumer to believe the drink is healthier than it really is. Armed with this knowledge, patients may choose to reach for more nutritious beverages when they are thirsty.

Once patients have become more conscious of their sugar consumption, dental hygienists can then help them remineralize or desensitize any weak areas in their dentitions. Remineralization can occur naturally from the calcium and phosphate found in saliva that build on existing crystal remnants of the dentition. Remineralization can occur only when there is both adequate saliva and low exposure to acids. Encouraging patients to increase their salivary flow while monitoring their diet will promote remineralization. Clinicians may also recommend an increase in fluoride exposure. Professional fluoride application during routine prophylaxis visits or the use of a prescription-strength fluoride treatment to take home and apply nightly are both good options.22

The pain of dentinal hypersensitivity can be reduced by identifying the cause and risk factors and introducing behavior modification techniques, such as using a dentifrice designed to reduce sensitivity.22 Dental hygienists can also recommend therapeutic fluoride treatments, either in-office or take-home, to reduce the pain caused by hypersensitivity.22

Drinking fluoridated community water is also important. Patients should be encouraged to replace their consumption of sugary drinks with water, as even a small decrease in the amount of sweetened drinks consumed makes a difference. Dental hygienists should also update parents/guardians about the hidden ingredients and lack of nutrients found in sugar-sweetened beverages and encourage them to replace these drinks with water or milk.13

Dental hygienists can also advocate for reduced consumption of sugar-sweetened drinks. They can ask their government legislators to increase taxes on sugary drinks.13 In 2014, California had two cities propose legislation to increase taxes on sugar-sweetened beverages.23 These measures were developed due to a recent Harvard University study that found increasing the price of soda caused consumers to avoid purchasing it.23 In Berkeley, California, voters decided that the city should begin taxing sugar-sweetened beverages at an increased rate of 1 cent per ounce. In the city of San Francisco, however, voters rejected the proposed tax.23

There are currently 15 countries, not including the US, that have special increased taxation regimens for sugar-sweetened beverages.14 In addition, there is a call for the US government to provide a dietary limit for added sugar to beverages. Currently, the federal government provides a list through the Child Nutrition Labeling Program to both the public and manufacturers that dictates what ingredients in what amount can be added to foods. Sugar, according to the government’s list, is generally regarded as a safe food choice. As a result, manufacturers are allowed to place as much sugar as they want into their food and beverages.13 Public health advocates have asked for sugar to be removed from this list so that limits can be placed on how much sugar is added to food and drinks. Further support from dental hygienists and consumers could help get this request granted.

CONCLUSION

Dental hygienists have a unique opportunity to educate the public on the growing concern of excessive consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages. The sugar and acid found in these drinks not only harm the dentition, but can also lead to systemic health problems. Dental hygienists need to help patients treat areas of the mouth that have already been damaged by excessive consumption of sugary drinks. Furthermore, providing education on how to read nutrition labels can help patients make better decisions about the beverages they consume. Government legislation may also help reduce consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages. Overconsumption of these drinks is an important public health topic and should be part of the dental hygienist’s agenda.

REFERENCES

- Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. Sugary Drinks. Available at: hsph.harvard.edu/ nutrition source/ healthy-drinks/sugary-drinks. Accessed February 24, 2015.

- Bleich SN, Wang YC. Consumption of sugarsweetened beverages among adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:551–555.

- Bleich SN, Wayng YC, Wang Y, Gortmaker SL. Increasing consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages among US adults: 1988-1994 to 1999- 2004. Am J Clin Nut. 2009;89:372–381.

- Rudd Center. Sugary Drink Facts. 2013. Available at: sugarydrinkfacts.org/resources/SugaryDrinkFACTS_Rep ort_Results.pdf. Accessed February 24, 2015.

- Babey SH, Jones M, Yu H, Goldstein H. Bubbling over: soda consumption and its link to obesity in California. Policy Brief UCLA Cent Health Policy Res. 2009(PB2009-5):1–8.

- Kaplowitz GJ. An update on the dangers of soda pop. Dent Assist. 2013;80:13–28.

- Naval S, Koerber A, Salzmann L, et al. The effects of beverages on plaque acidogenicity after a sugary challenge. J Am Dent Assoc. 2013;144:815–822.

- Cheng R, Yang H, Shao, M, et al. Dental erosion and severe tooth decay related to soft drinks: a case report and literature review. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2009;10:395–399.

- Zero DT, Fontana M, Martinez-Mier EA, et al. The biology, prevention, diagnosis and treatment of dental caries: scientific advances in the US. J Am Dent Assoc. 2009;140:25s–34s.

- Wilkins EM. Protocols for prevention and control of dental caries. Clinical Practice of the Dental Hygienist. 11th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams, & Wilkins; 2005:393–401.

- Indiana Dental Association. Drinks Destroy Teeth. Available at: drinksdestroyteeth.org/?p=129. Accessed February 24, 2015.

- Pan A, Hu FB. Effects of carbohydrates on satiety: differences between liquid and solid food. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2011;14:385–390.

- Giancoli A, Soto R. Sugary drinks: a big problem for little kids. Available at: first5la.org/files/ Sugar-Sweetened_ Drink_ Policy_Brief.pdf. Accessed February 24, 2015.

- Schmidt LA. New unsweetened truths about sugar. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:525–526.

- Yang Q, Zhang Z, Gregg EW, et al. Added sugar intake and cardiovascular disease mortality among US adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:516–524.

- National Institutes of Health. Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults. Available at: nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/obesity/ob_gdlns.pdf. Accessed February 24, 2015.

- Janssens JP, Shapira N, Debeuf P, et al. Effects of soft drink and table beer consumption on insulin response in normal teenagers and carbohydrate drink in youngsters. Eur J Cancer Prev. 1999;8:289–295.

- Malik VS, Popkin BM, Bray GA, Despres JP, Willett WC, Hu FB. Sugar-sweetened beverages and risk of metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes: a metaanalysis. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:2477–2483.

- Nielsen SJ, Popkin BM. Changes in beverage intake between 1977 and 2001. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27:205–210.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2014. Available at: cdc.gov/diabetes/pubs/statsreport14.htm. Accessed February 24, 2015.

- California Center for Public Health Advocacy. How sugar-sweetened beverages became a leading contributor to the obesity epidemic. Available at: kickthecan.info/files/documents/SSBs%20as%20leadi ng%20contributor_6.17.13.pdf. Accessed February 24, 2015.

- Darby ML, Walsh MM. Dental Hygiene Theory and Practice. 4th ed. St. Louis, Missouri: Saunders Elsevier; 2015.

- Frizell S. Nation’s first soda tax passed in California City. Time Magazine. Available at: time.com/3558281/soda-tax-berkeley. Accessed February 24, 2015.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. March 2015;13(3):52,55–57.