Serving Disadvantaged Populations

Public health dental hygienists are dedicated to providing oral care services to those who need it most.

Introduction

Manager, Professional Relations Sunstar Americas Inc

The inability of disadvantaged populations to access professional oral health care remains a significant problem in the United States. Opportunities abound for dental hygienists to work in alternative practice settings and, in 37 states, provide care directly to patients. While many dental hygienists will choose the private practice model upon graduation, others will take the path less traveled and seek out new practice settings. In this Sunstar Spotlight, we highlight public health dental hygiene—a specialty dedicated to serving those in need.

Katherine Lemoine Pelullo, RDH, MEd, from Tufts University School of Dental Medicine, provides insights into the magnitude of the access-to-care issue and discusses the role of the public health dental hygienist in ameliorating the problem.

Many dental professionals work in private practice their entire careers. While the way they provide treatment may change due to advances in techniques and technologies, the setting in which they practice remains the same. Unfortunately, the private practice model does not serve the thousands of Americans who do not have dental insurance and who cannot pay out-of-pocket for dental health care services. The oral and systemic health of individuals who are unable to access care are at great risk.

Poor oral health has significant health consequences. Dental caries is the most common chronic childhood disease—five times more common than asthma, and seven times more common than hay fever.1 More than 51 million school hours are lost each year due to dental-related illnesses.1 Approximately 50% of children age 5 to 9 have at least one caries lesion or restoration; this statistic increases to 78% once they reach 17.1

Accessing oral health care continues to be challenging for millions of the nation’s most vulnerable populations. Emphasizing the importance of oral health and its relationship to overall health is critical to improving the health of all Americans. This attitudinal change must be coupled with an examination of service-delivery models to identify oral health professionals and protocols that will improve access to care—including the use of public health dental hygienists.

ORAL HEALTH CRISIS

Achieving optimal oral health presents many challenges to individuals and families who have few resources. Barriers to care include limited income and/or no dental insurance, transportation issues, and the inability to take time off from work for dental appointments. Patients who are homebound face tremendous challenges in accessing care, and some require the use of ambulance vans to transport them to appointments. The level of reimbursement for providers in public programs is generally low and can be a disincentive for dental professionals to participate in these programs. Special patient populations, including those with developmental and physical disabilities and older adults, may face additional obstacles when seeking oral health care. In order to overcome these barriers, policy-makers need to be better informed about the importance of oral health to overall health and its integral relationship to systemic health.1

The United States Surgeon General’s 2000 report, Oral Health in America, brought the country’s oral health crisis to light, and encouraged the development of a national oral health plan to improve quality of life and eliminate health disparities.1 The report noted that this should include:

- Building an effective health infrastructure that meets the needs of every American and integrates oral health effectively into overall health

- Removing known barriers that affect patients’ treatment

- Utilizing public-private partnerships to improve oral health status1

Dental hygienists have responded to the Surgeon General’s call to improve the nation’s oral health over the past 14 years.1 In 2001, the American Dental Hygienists’ Association (ADHA) published the Access to Care Position Paper that stated, “It is the position of the ADHA that oral health care—a fundamental component of total health care—is the right of all people. Lack of access to oral health care is a critical issue in the US due to disparities in the health care delivery system. Dental hygienists must play a vital role in the solution to eliminate these disparities and assure quality oral health care for all.”2

Over the past 101 years, dental hygienists have worked in a variety of settings, including private dental offices, schools, long-term care facilities, and research, to name a few. State dental practice acts and supervisory regulations, however, have traditionally prohibited dental hygienists from having direct access to patients—limiting their ability to reach underserved populations.

![]() EXPANDING THE REACH

EXPANDING THE REACH

Enabling dental hygienists to practice to the full extent of their education and experience is integral to solving the nation’s access-to-care problems. Today, there are more than 50 baccalaureate degree-completion programs and over 20 master degree programs to help dental hygienists extend their reach into additional practice settings.3 The public health dental hygienist is dedicated to meeting the needs of underserved groups, such as low-income populations, pregnant women, older adults, and those with developmental, physical, or mental disabilities.4 Public health dental hygienists typically provide services within the traditional dental hygiene scope of practice. In some states, public health dental hygienists may provide oral health and educational services within a state preventive dental health program under general supervision, which means the dentist must authorize the services provided, but he or she need not be on-site.5 They may practice clinically or serve in administration or developmental roles. A variety of settings are available to public health dental hygienists, such as community oral health program development, community water fluoridation programs, Medicaid or public health administration, school-based dental clinics, mobile dental clinics, and long-term care facilities.4

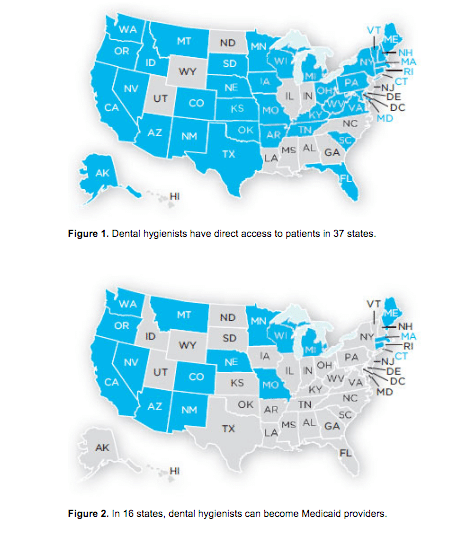

In the 37 states where dental hygienists have direct access to patients, public health dental hygienists may deliver advanced clinical services, including the provision of restorative care (Figure 1).5 The scope of practice varies by jurisdiction. For example, in Massachusetts, public health dental hygienists may provide the full range of dental hygiene services that are allowed in a private dental office under general supervision. They can administer key oral health treatments, including prophylaxis, root planing, application of fluoride treatments, and placement of sealants. However, they cannot administer local anesthesia because this service must be administered under the direct supervision of a dentist.

In Washington, public health dental hygienists can place sealants, apply fluoride varnish, and perform prophylaxis in community-based and school-based programs. Additionally, they can provide oral health services in senior centers. Clinicians working in these settings do so under general supervision.5 Public health dental hygienists in Nebraska can provide oral health services in public health and health-care related settings. Specifically, they are authorized to administer prophylaxis to children, and perform pulp vitality testing and preventive services (eg, fluoride and sealant application) under general supervision.5 West Virginia enables public health dental hygienists to offer patient education, nutritional counseling, oral screening with referral to a dentist, application of fluoride treatments and sealants, and prophylaxis under general supervision in hospitals, schools, correctional facilities, jails, community centers, long-term care facilities, nursing homes, home health agencies, group homes, state institutions, public health facilities, homebound settings, and accredited dental hygiene education programs.5

Each state has its own requirements that must be met before public health dental hygienists can provide care directly to patients. In Massachusetts, public health dental hygienists must maintain a valid dental hygiene license to practice in the state, have practiced full-time for at least 3 years or worked at least 4,500 hours part-time, and completed additional training requirements. These include the completion of at least 6 hours of hands-on experience in a public health setting, and a minimum of 4 units of didactic continuing education in the following areas: infection control and US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Guidelines for Infection Control in Dental Health-Care Settings, 2003; risk management for practice in a public health setting; and management of medical emergencies. The Massachusetts Department of Public Health, Office of Oral Health, has developed an online toolkit to guide dental hygienists through the process of becoming a public health dental hygienist (mass.gov). Once all of the requirements are met, Massachusetts public health dental hygienists are allowed to purchase equipment and establish a practice.6

In Massachusetts, a public health setting includes, but is not limited to, residences of the homebound; schools; Head Start programs; nursing homes; licensed long-term care facilities, clinics, community health centers, and hospitals; medical facilities; prisons; residential treatment facilities; federal, state, or local public health programs; mobile dental facilities; and portable dental programs.5 The state of Massachusetts also requires that public health dental hygienists maintain a collaborative agreement with a local or state government agency or institution, or a licensed dentist who agrees to provide the appropriate level of communication and consultation with the public health dental hygienist to ensure patient health and safety. The collaborative agreement must also include a signed affidavit that confirms successful completion of the required continuing education. This agreement must be reviewed annually.6

In order to become a public health dental hygienist in Washington, licensed dental hygienists must have 2 years of clinical experience, and they must report data on the patients they serve to the state’s Department of Health. In West Virginia, licensed dental hygienists must have been in practice for at least 2 years with a minimum of 3,000 hours of clinical practice experience. In addition, they must complete 6 continuing education units. The supervising dentist and the public health dental hygienist must provide the state board of dental examiners with an annual report of care.5

The scope of practice for public health dental hygienists varies widely between states. Some allow public health dental hygienists to provide comprehensive preventive care—including local anesthesia administration—while others may limit direct access to screenings and fluoride and sealant application. To date, the District of Columbia and 13 states—Hawaii, Utah, Wyoming, North Dakota, Illinois, Indiana, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, North Carolina, Delaware, and New Jersey—prohibit direct access of any kind.5

REIMBURSEMENT

Dental hygienists who wish to receive payment for services provided directly to patients need to apply for a national provider number. In the 16 states where dental hygienists are allowed to become Medicaid providers, clinicians need to enroll to begin submitting for payment (Figure 2).7 Third-party private payers have different rules, and dental hygienists must inquire about the process for becoming an approved provider with individual companies.8

CONCLUSION

Dental hygienists are key to improving access to care problems in the United States. By expanding the settings in which dental hygienists are allowed to practice, more people will receive the oral health care services they need. For dental hygienists interested in this professional track, the path can be arduous, but also tremendously gratifying. Helping disadvantaged populations receive professional oral health care services and improve both their oral and systemic health is the public health dental hygienist’s passion.

A DAY IN THE LIFE OF A PUBLIC HEALTH DENTAL HYGIENIST IN PRACTICE

A typical work day for a Massachusetts public health dental hygienist in clinical practice begins long before arriving at the site where patients will be treated. Portable equipment must be inspected, loaded, and transported to the location. This armamentarium can include large, bulky items, such as a compressor, which may weigh upwards of 60 lbs (Figure 3). Instruments must be packaged, transported, and sterilized according to infection control standards for mobile and portable programs. All dental and program supplies must be restocked and prepared for transport. In Massachusetts, where public health dental hygienists can bill Medicaid directly for services provided, clinicians generally check all patients’ eligibility status and claims history to prevent duplication of any recent treatment provided in a private dental office or community health center.

Upon the clinician’s arrival at the treatment site, equipment and supplies must be unloaded and set up. A public health dental hygienist usually meets with a facility representative. In school settings, this is typically the nurse. Before the first patient arrives, the public health dental hygienist may review records of the patients scheduled for the day and follow-up on any referral issues or questions from the previous visit. It is then time to actually start treating patients. Depending on the site and services provided, the schedule may include one patient or as many as 10 patients.

At the end of the treatment day, the public health dental hygienist must complete all required forms that will be sent home to families and provided to the facility representative. Equipment is disassembled and instruments are placed in containers in preparation for transport. Typically, a brief meeting between the dental hygienist and the facility representative occurs, during which they review patient records from the day and identify individuals who require follow-up. Then, the public health dental hygienist may need to contact patient families via telephone to help them secure a dental home.

After arriving home, the public health dental hygienist must unload, autoclave all instruments, and complete necessary billing paperwork.

REFERENCES

- United States Department of Health and Human Services. Oral Health In America: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, Md: National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research; 2000.

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association. Access to Care Position Paper, 2001. Available at: adha.org/resourcesdocs/7112_Access_to_ Care_Position_Paper.pdf. Accessed October 7, 2014.

- Foley M. Rise of the public health dental hygienist. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2014;12(Suppl 10):26–27.

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association. Careers in Public Health. Available at: adha.org/public-health. Accessed October 7, 2014.

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association. Direct Access States. Available at:?adha.org/resources-docs/7513_Direct_Access_to_Care_from_DH.pdf. Accessed October 7, 2014.

- Board of Registration in Dentistry, 234 Code of Massachusetts Regulations. Available at: lawlib.state.ma.us/source/mass/cmr/cmrtext/234CMR5.pdf. Accessed October 7, 2014.

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association. Direct Medicaid Reimbursement 2014. Available at: adha.org/resources-docs/7526_Medicaid_Map.pdf. Accessed October 7, 2014.

- Byrd T. Rules of reimbursement. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2014;12(Suppl 10):24–25.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. November 2014;12(11):17–20.