Screening for Obstructive Sleep Apnea

The incorporation of simple screening procedures in the dental office can help expedite an early diagnosis and successful treatment of OSA.

This course was published in the April 2010 issue and expires April 2013. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Identify the symptoms associated with obstructive sleep apnea.

- Understand the role of established screening tools in identifying risk factors for obstructive sleep apnea.

- Describe the role of the dental hygienist in the identification of risk factors associated with obstructive sleep apnea.

- Describe the various treatment options for patients with obstructive sleep apnea.

Many patients visiting the dental office have undiagnosed chronic diseases. In addition to the impact of these undetected diseases on patients’ general and oral health, social and work-related implications are also relevant.

The relationship between obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and the high incidence of transportation accidents in the United States is an example of an undiagnosed disease causing often tragic societal implications. A 2008 study found that people who have sleep apnea are at double the risk of being in a car accident.1 The National Transportation Safety Board also issued a recommendation in October 2009 to screen all truck and bus drivers, commercial pilots, train engineers, and merchant sailors for sleep apnea.2 The early recognition and treatment of OSA can significantly reduce those associated risks. Dental professionals are well suited to recognize the symptoms of OSA and provide patients with a physician referral for further evaluation.

WHAT IS OSA?

Obstructive sleep apnea is a common sleep disorder that causes recurrent episodes of upper airway obstruction. The blocked breathing experienced by those who have OSA results in a decrease in airflow and ventilation during sleep.3 Figure 1 illustrates the anatomy of the throat and breath flow of a patient who has OSA.

OSA also causes interrupted sleep and a decrease in oxygen levels in the blood known as hypoxemia.3 Hypoxemia leads to the development of many adverse systemic effects, which are listed in Table 1.4,5

The interrupted sleep episodes experienced by individuals who have OSA can cause a variety of symptoms (see Table 2). Daytime symptoms include daytime sleepiness, depression, difficulties with concentration or memory, fatigue, gastric reflux, morning headaches and a history of work-related accidents.1 Nighttime symptoms include awakenings or arousals from the obstructed airway episodes, loud snoring, insomnia, and frequent nighttime urination.6

Bruxism and xerostomia are symptoms that are often not immediately associated with OSA. Xerostomia is common among people who have OSA because of the open mouth episodes experienced during the night.7,8 Bruxism, which takes place during the arousal episodes, is associated with sudden awakenings from the obstruction.9

Anatomical characteristics are also indicators of OSA. Patients who have sleep apnea may exhibit specific intraoral traits, such as shape of the soft palate, enlargement of the lateral pharyngeal walls, and the mandible profile.1 Table 3 provides a list of the physical characteristics associated with OSA, most of which can be easily identified during a routine dental exam.

TABLE 1. ADVERSE SYSTEMIC EFFECTS ASSOCIATED WITH HYPOXEMIA.4-6

- Arrythmias

- Atherosclerosis

- Congestive heart failure

- Coronary artery disease

- Diabetes

- Hypertension

- Pulmonary hypertension*

- Stroke

*Abnormally high pressure in the arteries of the lungs that causes the right side of the heart to work harder

Gender differences also play a role in OSA. For example, although men typically exhibit more of the physical characteristics of OSA, such as large tonsils, a wide uvula, and high tongue, it is women with large tonsils and a retrognathic profile who are more likely to develop OSA.10 Also, women typically do not present with the classic symptoms of OSA, such as snoring and daytime sleepiness. Their symptoms may be less definitive, such as insomnia and depression. Obesity is another risk factor associated with OSA, although it is not a necessary component of the disorder.5

TABLE 2. SYMPTOMS OF OSA.6,7,9

- Bruxism

- Daytime sleepiness

- Depression

- Difficulties with concentration or memory

- Fatigue

- Frequent nighttime urination

- Gastric reflux

- Insomnia

- Loud snoring

- Morning headaches

- Sudden nighttime awakening

- Work-related accidents

- Xerostomia

Lifestyle characteristics can also indicate the possibility of OSA. Behaviors, such as high use of alcohol, sedatives, or tranquilizers, are also risk factors because these substances relax the muscles of the throat. Additionally, smoking increases the risk of OSA by three times.11

DIAGNOSIS

Approximately, 80% of all moderate to severe cases of OSA in middle-aged men and women go undiagnosed.12 A definitive diagnosis of OSA is achieved through a sleep test known as polysomnography, which involves an overnight stay in a sleep laboratory. Polysomnography provides a recording of the patients’ brain waves (EEG); heart rhythm (ECG); air flow; eye, chin, chest, and limb movements; oxygen saturation; and snoring in order to determine if the patient has a sleep disorder like OSA.5 This extensive testing is only used in patients who exhibit the common symptoms of OSA or the systemic effects associated with OSA.

TABLE 3. PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS ASSOCIATED WITH OSA.10,20

- Large neck circumference

- High tongue

- Large tonsils

- Narrow pharyngeal airspace

- Obesity

- Retrognathic profile

- Wide uvula

Although polysomnography is used as the definitive diagnosis of OSA, early detection and recognition of OSA risk factors are critical in the identification of patients who may not present with classic OSA symptoms, such as loud snoring and sudden gasping for air during the sleep cycle. Two screening tools—the Mallampati examination and the Epworth Sleepiness Scale—are currently used by medical professionals to screen patients for undiagnosed OSA and to identify patients who have airways that may be difficult to intubate.

The Mallampati examination is used by anesthesiologists, pulmonologists, and respiratory therapists to estimate the size of the opening of the oropharynx by comparing the size and shape of the soft palate and uvula to the back of the throat (Figure 2).13 Research has confirmed the usefulness of this scoring system in identifying patients who may be at risk for OSA.14 Patients with a high classification (3 or 4) on the Mallampati examination should be referred to their primary care physician for further evaluation. Patients who are classified as a 3 or 4 are also at greater risk of having a difficult airway for endotracheal intubation because of the limited opening of the oropharynx.15 Dental professionals who practice sedation dentistry need to be aware of all patients who may have a difficult airway to intubate in order to avoid complications during sedation.

The Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) is used by pulmonologists and polysomnographers as a screening tool for sleep apnea (Figure 3).16 The ESS identifies patients who score greater than 10 as being at risk for sleep apnea. The scale is a simple questionnaire used to evaluate daytime sleepiness.16 Both the Mallampati and ESS are simple tools and can be easily used by dental hygienists.

The Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) is used by pulmonologists and polysomnographers as a screening tool for sleep apnea (Figure 3).16 The ESS identifies patients who score greater than 10 as being at risk for sleep apnea. The scale is a simple questionnaire used to evaluate daytime sleepiness.16 Both the Mallampati and ESS are simple tools and can be easily used by dental hygienists.

TREATMENT

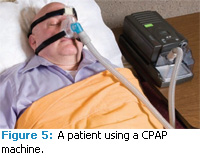

The most common treatment for OSA is the use of a continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) device (Figures 4 and 5). This device is used during sleep to stent the airway open and eliminate the obstruction. Figure 6 illustrates how the CPAP device opens the airway.

Lifestyle changes such as losing weight, smoking cessation, or sleeping on the side instead of on the back can also be recommended.11 For some patients, wearing an appliance during sleep hours to direct the mandible anteriorly—which encourages the tongue and soft palate to stay forward and not close off the airway during sleep—may be helpful. This device, known as an anterior mandibular positioning device (AMP), may be used to alleviate some of the obstructive effects of sleep apnea.17 However, some patients report a number of side effects and symptoms caused by the appliance including dry mouth and temporomandibular joint symptoms.1

Lifestyle changes such as losing weight, smoking cessation, or sleeping on the side instead of on the back can also be recommended.11 For some patients, wearing an appliance during sleep hours to direct the mandible anteriorly—which encourages the tongue and soft palate to stay forward and not close off the airway during sleep—may be helpful. This device, known as an anterior mandibular positioning device (AMP), may be used to alleviate some of the obstructive effects of sleep apnea.17 However, some patients report a number of side effects and symptoms caused by the appliance including dry mouth and temporomandibular joint symptoms.1

Surgical procedures can also be recommended for patients who are intolerant to CPAP. The surgical procedure should be selected based on the patient’s airway anatomy, medical status, and severity of disorder.18

THE ROLE OF THE DENTAL HYGIENIST

Dental hygienists have an expanding role in collaborating with other health care professionals in the early identification of risk factors associated with systemic conditions. Dental hygienists currently use several risk assessment tools during a routine dental hygiene exam to recognize conditions and factors that predispose a patient to certain conditions or diseases. Regarding OSA, dental hygienists can include an assessment of xerostomia, bruxism, and the size of the tongue and airway opening into their routine oral exams. By implementing the ESS and the Mallampati examination into their inspection of the oral cavity, the dental hygienist is in a unique position to recognize patients who may have undiagnosed OSA.19 By incorporating these relatively simple screening procedures into the dental exam and health history, early screening is possible. Patients can then be referred to their primary care physicians for further testing to expedite early diagnosis and treatment of OSA.

REFERENCES

- Mulgrew AT, Nasvadi G, Butt A, et al. Risk and severity of motor vehicle crashes in patients with obstructive sleep apnoea/hypopnoea. Thorax. 2008;63:536-541.

- National Transportation Safety Board. Safety Recommendation. Available at: www.ntsb.gov/Recs/letters/2009/H09_15_16.pdf. Accessed March 24, 2010.

- Remmers JE, deGroot WJ, Sauerland EK, Anch AM. Pathogenesis of upper airway occlusion during sleep. J Appl Physiol. 1978;44:931-938.

- Wolk R, Somers VK. Cardiovascular conse – quences of obstructive sleep apnea. Clin Chest Med. 2003;24:195-205.

- Lee W, Nagubadi S, Kryger MH, Mokhlesi B. Epidemiology of obstructive sleep apnea: a population-based perspective. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2008;2:349-364.

- Patil SP, Schneider H, Schwartz AR, Smith PL. Adult obstructive sleep spnea. Chest. 2007; 132: 325-337.

- Oksenberg A, Froom P, Melamed S. Dry mouth upon awakening in obstructive sleep apnea. J Sleep Res. 2006;15:317-320.

- Al Lawati NM, Patel SR, Ayas NT. Epidemiology, risk factors, and consequences of obstructive sleep apnea and short sleep duration. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2009;51:285-293.

- Oksenberg A, Arons E. Sleep bruxism related to obstructive sleep apnea: the effect of continuous positive airway pressure. Sleep Med. 2002;3:513-515.

- Dahlqvist J, Dahlqvist A, Marklund M, Berggren D, Stenlund H, Franklin KA. Physical findings in the upper airways related to obstructive sleep apnea in men and women. Acta Otolaryngol. 2007;127:623-630.

- Mayo Clinic. Sleep Apnea, Risk Factors. Available at: http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/sleepapnea/DS00148/DSECTION=risk-factors. Accessed March 24, 2010.

- Young T, Evans L, Finn L, Palta M. Estimation of the clinically diagnosed proportion of sleep apnea syndrome in middle-aged men and women. Sleep. 1997;20:705-706.

- Mallampati SR, Gatt SP, Gugino LD, et al. A clinical sign to predict difficult tracheal intubation: a prospective study. Can Anaesth Soc J. 1985;3:429-434.

- Nuckton TJ, Glidden DV, Browner WS, Claman DM. Physical examination: mallampati score as an independent predictor of obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep. 2006;29:903-908.

- Hiremath AS, Hillman DR, James AL, Noffsinger WJ, Platt PR, Singer SL. Relationship between difficult tracheal Intubation and obstructive sleep apnea. Br J Anaesth. 1998; 80: 606-611.

- Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep. 1991;14:540-545.

- Clark GT, Sohn JW, Hong CN. Treating obstructive sleep apnea and snoring: assessment of an anterior mandibular positioning device. J Am Dent Assoc. 2000;131:765-771.

- Li KK. Surgical management of obstructive sleep apnea. Clin Chest Med. 2003;24:365-370.

- Padma A, Ramakrishnan N, Narayanan V. Management of obstructive sleep apnea: a dental perspective. Indian J Dent Res. 2007; 18: 201-209.

- Schellenberg JB, Maislin G, Schwab RJ. Physi cal findings and the risk for obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:740-748.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. April 2010; 8(3): 54-57.