THARAKORN / ISTOCK / THINKSTOCK

THARAKORN / ISTOCK / THINKSTOCK

Reducing Muscle Workload

The use of cordless handpieces may help dental hygienists mitigate their risk of musculoskeletal disorders.

The high prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders (MSD) among dental professionals is well documented.1–8 Research suggests that the prevalence of work-related musculoskeletal pain among dentists and dental hygienists ranges between 64% and 93%;3,4 although, the number of MSDs among dental professionals may be underreported.5 Dental hygienists in particular demonstrate high levels of MSDs. While they can occur in the shoulders, back, or neck, the highest prevalence of MSDs is seen in the hands and wrists.1,3,4,6 Injuries to the wrists and hands arise from holding instruments in static positions and performing highly repetitive tasks. Therefore, it is not surprising that dental hygienists face high risks for developing carpal tunnel syndrome compared with other professions.1,6,7 Despite advances in ergonomically designed instruments, there is much work to be done.

Evidence shows that MSDs are a significant occupational hazard for dental hygienists, impacting their productivity and initiating premature departure from the profession.2,7 In light of the high prevalence of MSDs among dental hygienists, factors that contribute to the development of work-related MSDs must be identified and mitigated. Dental hygienists need to adopt ergonomic principles such as?holding the neck, trunk, and wrist in a neutral position;9 using appropriate lighting; adjusting the height and location of seating; donning properly fitted gloves; and wearing loupes.10 However, a significant portion of a dental hygienist’s workload still requires repetitive movements, precise control of forces, and maintaining static positions. These factors are especially linked to the development of hand and wrist pain. In an effort to mitigate these risks, manufacturers have sought to design instruments based on ergonomic factors. Researchers have begun to test these instruments and contribute to the understanding of how characteristics such as balance, diameter, weight, padding, and surface texture affect the risk of developing MSDs.8,11,12

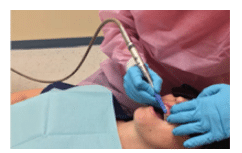

The creation of powered instruments has been an important milestone in dental hygiene practice. For example, coronal polishing has evolved from the porte polisher, to slow speed handpieces, to specialized prophylaxis handpieces. Powered instruments have been created in an effort to improve effectiveness and efficiency, thereby reducing the workload on dental hygienists. Ergonomic adaptations are being continually made to these instruments, such as the introduction of short and lightweight handpieces. A traditional problem with handpieces has been the constraint of cords or hoses that provide power to instruments. These add weight and create resistance during instrumentation (Figure 1). Cord drag or “cord catching” has been thought to increase muscle stress and workload; however, this has only recently been studied.13 Many clinicians wrap cords around their wrists or fingers or wrap them around bracket tables in efforts to reduce cord resistance and improve maneuverability. The introduction of a swivel hose mechanism appears to have mitigated the cord catching problems observed in earlier designs, but the presence of any cord or hose can still cause drag.

Developments in electric motors and battery technology have made it possible to build powered instruments without cords or hoses to improve efficiency and reduce the risks of MSDs. Cordless tools have been developed for construction, manufacturing, and medicine, with dental product manufacturers following suit.14,15 Today, cordless prophylaxis handpieces provide clinicians with another option.

In principle, cordless hygiene handpieces provide improved portability and ease of movement, while reducing cord restriction and cord drag. Thus, the clinician may expect a reduced muscle workload when using a cordless handpiece compared with a traditional corded handpiece, which may decrease the risk of MSDs. In industry, battery powered tools were developed in an effort to reduce MSDs and improve efficiency,14,15 but the purported ergonomic benefits have yet to be tested.

Recently, we conducted the first study—and the only clinical research to date—to quantitatively determine if a cordless handpiece reduces muscle workload compared with a corded version.13 The clinical study compared cordless and corded handpieces in terms of muscle activity and duration. Surface electromyography (sEMG) was used to quantify forearm muscle activity among three handpieces during simulated coronal tooth polishing. Thirty dental hygienists, with a mean age of 37.7 years who had between 1 year and 20+ years of clinical experience, completed the study. Three handpieces were tested: two corded and one cordless. Muscle activity of four forearms muscles—flexor digitorum superficialis, flexor pollicis longus, extensor digitorum communis, and extensor carpi radialis brevis—were analyzed with sEMG (Figure 2). Handpieces were randomized and each subject polished four different areas of the mouth using their normal procedures. At the conclusion of the study, an end-user satisfaction questionnaire was completed. Results suggest that although levels of muscle activity did not differ significantly between the three handpieces, the total muscle activity was the lowest for the cordless handpiece. On average, polishing using the cordless handpiece took 30 seconds less time than with either of the corded versions, which, in turn, reduced stress and muscle load. It was postulated that the elimination of cord drag reduced the duration of polishing, which explains the decreased total muscle activity. The cordless handpiece scored the highest among the handpieces tested for maneuverability and comfort. Subjects reported that the ease of movement and lack of cord resistance were important in determining their preference. Participants stated that the cordless handpiece was quieter and produced even, sufficient power throughout the polishing sequence. Overall, 50% of the participants preferred the cordless handpiece vs the two corded devices.

Polishing’s repetitive motions place continuous loads on the muscles and tendons of the wrists and hands. Reducing the total muscle workload via the use of a cordless handpiece may help to decrease the risk of MSDs. Future studies should examine a broader array of handpieces from a larger, more diverse subject population, over a longer time period.

PRACTICAL IMPLICATIONS

The repetitive movements common in dental hygiene practice place high workload demands on the muscles of the forearms and hands. It is likely that such tasks lead to the development of MSDs, which may explain the high prevalence among dental hygienists. Ergonomic improvements to instruments may help decrease MSDs, and a cordless handpiece is one such development. Further research is needed to test and refine the development of handpieces in order to reduce the stress and workload on the clinician. However, using instruments that have been shown to reduce muscle workload is unlikely to fully eliminate MSDs. Rather, reducing this risk requires a multifaceted ergonomic approach that includes selecting appropriate equipment, organizing the workspace, and adopting postures and movements that minimize stresses and workload placed on the body.10,13 The development and more widespread use of cordless equipment, such as curing lights and hygiene handpieces, is likely to continue to grow. Dental hygienists should utilize the evidence-based ergonomic knowledge that is currently available, as well as keep abreast of new developments in order to reduce their risk for developing MSDs.

References

- Anton D, Rosecrance J, Merlino L, Cook T. Prevalence of musculoskeletal symptoms and carpal tunnel syndrome among dental hygienists. Am J Ind Med. 2002;42:248–257.

- Osborn JB, Newell KJ, Rudney JD, Stoltenberg JL. Musculoskeletal pain among Minnesota dental hygienists. J Dent Hyg. 1990;64:132–138.

- Åkesson I, Johnsson B, Rylander L, Moritz U, Skerfving S. Musculoskeletal disorders among female dental personnel -clinical examination and a 5-year follow-up study of symptoms. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 1999;72:395–403.

- Szyma?ksa J. Disorders of the musculoskeletal system among dentists from the aspect of ergonomics and prophylaxis. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2002;9:169–173.

- Lalumandier JA, McPhee SD, Parrott CB, Vendemia M. Musculoskeletal pain: prevalence, prevention, and differences among dental office personnel. Gen Dent. 2001;49:160–166.

- Leigh JP, Miller TR. Occupational illnesses within two national data sets. Int J Occup Environ Health. 1998;4:99–113.

- Osborn JB, Newell KJ, Rudney JD, Stoltenberg JL. Carpal tunnel syndrome among Minnesota dental hygienists. J Dent Hyg. 1990;64:79–85.

- Simmer-Beck M, Branson BG. An evidence-based review of ergonomic features of dental hygiene. Work. 2010;35:477–485.

- Kott K, Lemaster MF. Injury prevention with physical therapy. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2014;12(4):26–29.

- Ayoub HM, Darby M. Ergonomic best practices. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2013;11(4):3–34.

- Simmer-Beck M, Bray KK, Branson B, Glaros A, Weeks J. Comparison of muscle activity associated with structural differences in dental hygiene mirrors. J Dent Hyg. 2006;80:8.

- Dong H, Barr A, Loomer P, Laroche C, Young E, Rempel D. The effects of periodontal instrument handle design on hand muscle load and pinch force. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006;137:1123–1130.

- McCombs GB, Russell D. Comparison of corded and cordless handpieces on forearm muscle activity, procedure time, and ease of use during simulated tooth polishing. J Dent Hyg. 2014;88:386–393.

- Bjorlingson N, Rengstedt M. Advanced battery tools for ergonomics and quality assurance in aircraft assembly. SAE Int J Aerosp. 2012;5:62–67.

- Kim FJ, Sehrt D, Molina WR, Pompeo A. Clinical use of a cordless laparoscopic ultrasonic device. JSLS. 2014;18:e2014.001153.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. April 2016;14(04):24–26,29.