SELVANEGRA / ISTOCK / THINKSTOCK

SELVANEGRA / ISTOCK / THINKSTOCK

Recognizing the Signs Of Crohn’s Disease

Oral health professionals should be aware of the oral manifestations of this gastrointestinal condition in order to facilitate early diagnosis.

This course was published in the March 2016 issue and expires March 31, 2019. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Identify the diagnostic criteria for Crohn’s disease.

- List the oral signs and symptoms of this gastrointestinal condition.

- Explain the treatment strategies for Crohn’s disease.

- Discuss the oral health care considerations for treating this patient population.

Environmental, behavioral, and genetic factors may contribute to the development of IBD. The use of tobacco at a young age and gastroenteritis have both been implicated independently as risk factors for IBD.8 New evidence suggests that those who were prescribed high levels of antibiotics in early childhood and those with low vitamin D levels are at increased risk for IBD, especially Crohn’s disease.9,10

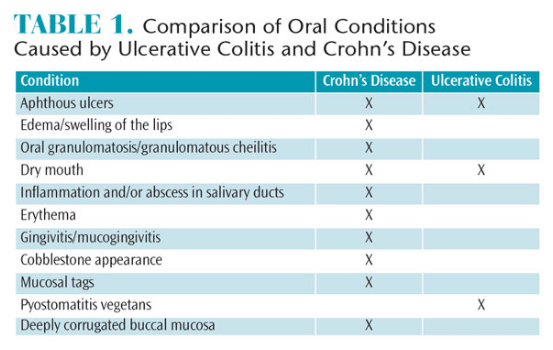

Both Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis are autoimmune disorders with similar signs and symptoms that can range from mild to severe. They also have periods of activity and remission.8 Symptoms for Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis include abdominal cramping, diarrhea, and areas of ulceration within the intestinal tract that can cause intestinal bleeding.2,7 Patients with both variations of IBD may experience malnutrition and anemia due to impaired absorption of vitamins B, D, folic acid, iron, and other critical nutrients. Malnutrition and anemia can cause serious oral health problems, including erythema, edema, angular cheilitis, glossitis, burning mouth syndrome, candidiasis, leukoplakic patches, and gingivitis.2,7,11,12 Ulcerative colitis can cause pyostomatitis vegetans, an uncommon oral manifestation that results in yellow, pus-filled lesions that frequently present with “snail track” patterns. Table 1 provides a comparison of the oral manifestations of both Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis.13

This article will focus on the diagnostic signs and symptoms of Crohn’s disease, as well as considerations for treatment of patients with this gastrointestinal disorder.1

REACHING A DEFINITIVE DIAGNOSIS

REACHING A DEFINITIVE DIAGNOSIS

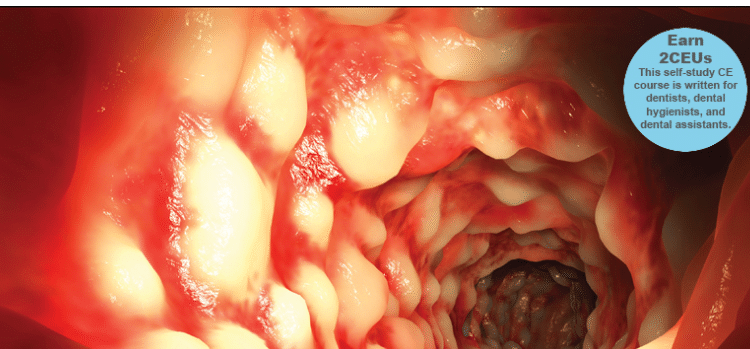

Today, the diagnosis of Crohn’s disease is made via integrative interpretation of clinical, radiographic, and laboratory analyses.11 Colonoscopy, ileoscopy, and relevant biopsies are essential to making an accurate diagnosis at the junction of the ileum and colon. Endoscopic findings include skip lesions (alternating areas of ulceration and healthy tissue), cobblestoning (uneven projections of unaffected mucosa surrounded by ulcers that can cause longitudinal or circumferential fissures), and strictures.14–16 While these are considered the gold standard for the diagnosis of Crohn’s disease, subjective assessments based on physical exams and patients’ descriptions of symtomology can also be considered.7,8 Definitive symptomatology includes the presence of non-necrotizing granulomatous inflammation within the submucosal connective tissue of bowel or oral tissues.17

Crohn’s disease most frequently occurs in the distal portions of the small intestine, where the ileum approaches the large intestine. One third of cases occur in the colon itself.7 In addition to the location of intestinal lesions, patients are also phenotyped using the Montreal classification, which considers age at diagnosis, disease site modifiers, and whether other autoimmune diseases are present.7 Once a definitive diagnosis is made, treatment is determined based on the location and severity of the disease.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS OF CROHN’S DISEASE

Common extraintestinal manifestations of Crohn’s disease include osteoporosis; asthma; changes to the skin such as psoriasis; and the presence of other autoimmune conditions such as kidney stones or polyarticular arthritis.7 Crohn’s disease can also cause sensory impairments, such as hearing loss, and eye problems, including uveitis.8

Chronic inflammatory disorders that overlap with Crohn’s disease may increase the risk for other systemic conditions such as autoimmune thrombocytopenia, autoimmune pancreatitis (resulting in type 1 diabetes), autoimmune hepatitis, psoriasis, or gangrene.7 Patients with Crohn’s disease are also at increased risk of cancer and are three times more likely to develop life-threatening blood clots.2

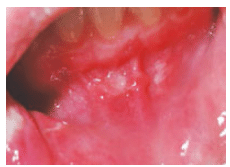

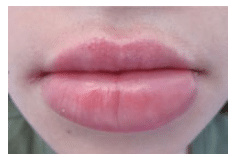

Oral manifestations of Crohn’s disease are not uncommon—especially in pediatric populations—and may be the first signs of the disease.9 Visible oral manifestations are similar to those found in the intestine, including cobblestone appearance of the mucosa, deep linear ulcerations, and mucosal tags. Oral manifestations may also include swelling of the lips, angular cheilitis, hyperplasia of erythematous gingiva,14 and recurrent ulcerations (Figure 1).11,12 Orofacial granulomatosis, or swelling of the orofacial area (Figure 2), is suggestive of Crohn’s disease and typically appears without accompanying intestinal symptoms.18–21 Recent literature notes that orofacial granulomatosis manifests in almost half of children and 20% to 50% of adults with Crohn’s disease.22 Whether orofacial granulomatosis is an oral manifestation of Crohn’s disease or a separate inflammatory condition remains debatable. Because orofacial granulomatosis may be an early indicator of Crohn’s disease, children who present with this condition should be evaluated for Crohn’s disease to facilitate early diagnosis.22

Esophageal involvement is also common.23 Symptoms of esophageal involvement may include dysphagia, heartburn, or acid reflux caused by esophageal damage/lesions, including lichen planus. Therefore, patients should be evaluated for signs of upper gastrointestinal symptoms.23 Knowledgeable oral health professionals can be instrumental in recognizing relevant signs and symptoms and referring patients to their physicians for further examination and diagnosis.

TREATMENT AND MANAGEMENT STRATEGIES

Crohn’s disease symptoms recur without a clear pattern and can be mild, moderate or severe. Treatment of Crohn’s Disease is determined by disease location, activity, and severity. These factors, when combined with the Crohn’s phenotype and imaging from endoscopic examination, are key in predicting the disease sequelae and potential complications.7

Traditional treatments for Crohn’s disease include pharmacotherapy and surgery. Medication regimens consist of five main pharmacological approaches: anti-inflammatory medications (sulfasalazine, mesalamine), steroidal therapies (prednisone), antibiotics (metronidazole, ciprofloxacin), immunomodulators (methotrexate, azathioprine), and biologic therapies (inflixiban, adalimumab).2,7 Almost 75% of individuals with the disease will eventually require surgical therapy such as strictureplasty, colectomy, proctocolectomy, or conservative surgical resection of the diseased bowel.2,24 Patients may also require other dietary interventions, including enteral nutrition.

Optimal treatment for Crohn’s disease remains controversial. Currently, two principal strategies are used: a traditional step-up approach and a top-down approach. In the step-up approach, corticosteroids or mesalamine products are introduced with subsequent advancement to immunomodulators or anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents, depending on disease severity. In the top-down approach, treatment begins with anti-TNF agents.14 Although earlier reports suggested exclusion of specific food types as a possible treatment,19 a Cochrane review concluded that corticosteroid therapy is more effective than enteral nutrition for inducing remission of active Crohn’s disease.25

CONSIDERATIONS FOR ORAL HEALTH CARE

Patients with mild manifestations of Crohn’s disease may receive dental care without complications. Oral manifestations of the disease are not typically problematic, may not need specific oral treatment, and, most often, resolve over time.19 But for patients who exhibit the recurrent aphthous ulcerations that occur in 10% of those affected, topical steroids may reduce healing time of ulcers and help alleviate resultant pain.26,27 In a recent study of pediatric patients with Crohn’s disease, a multidrug treatment that included azathioprine appeared to help mitigate the oral manifestations.21 Some patients with Crohn’s disease, however, may present with large oral ulcers that require treatment with biologics (specific proteins as opposed to chemical medications) to manage these lesions.27

Many of the medications prescribed for Crohn’s disease are immunosuppressants and biologics that may cause myriad oral and systemic side effects. For example, patients with Crohn’s disease who are taking biologics are at increased risk for infections, such as tuberculosis and hepatitis. These patients should be highly encouraged to remain up to date on their vaccinations, including influenza, pneumococcal, hepatitis A, hepatitis B, tetanus, diphtheria, humanpapilloma virus, pertussis, and polio. Patients who are immunocompromised should receive immunizations that do not contain viable microbes.7

Other commonly prescribed Crohn’s medications include corticosteroids, which help reduce the inflammatory process of the disease and promote healing. Patients who take corticosteroids for long periods often require careful monitoring of blood pressure and blood glucose levels.8 Oral health professionals should note in the patient’s chart to monitor blood pressure and blood glucose levels at each visit to ensure safe treatment. Treatment alterations, such as scheduling short appointments in the morning, may be necessary.

Smoking is a risk factor for Crohn’s disease. In fact, smokers are two times more likely to develop Crohn’s disease than nonsmokers.2 Smoking is also a risk factor for Crohn’s-related complications, increasing the occurrence of fistulas and intestinal strictures. Additionally, smoking can prolong flare ups and interfere with prescribed pharmacotherapies and other medical treatments.7 As with all patients, oral health professionals should encourage patients with Crohn’s disease to quit tobacco use.

Crohn’s disease frequently interferes with the absorption of nutrients, causing malnutrition. Clinicians should be aware of oral signs of malnutrition and the resultant deficiencies in vitamins and minerals, which can cause a variety of oral implications. Anemia can increase the risk of periodontal diseases, while other nutrient deficiencies can cause candidiasis and angular cheilitis.

Crohn’s disease makes it difficult to digest some foods. Whole grain and high-fiber foods can exacerbate symptoms of cramping and diarrhea. Small, frequent meals that are soft in consistency, have minimal fiber, and are low in carbohydrates may be recommended to ease digestion. However, this type of diet may increase caries risk. As such, oral health professionals should carefully assess caries risk, provide appropriate patient education, implement caries risk management plans, and offer nutritional counseling, as necessary.

In patients with Crohn’s disease, pharmacotherapy, extraintestinal manifestations, and/or concurrent autoimmune conditions are considerations for oral health professionals. Osteoporosis and asthma are other common conditions that may be seen in those with Crohn’s disease. Past or ongoing bisphosphonate therapy for the treatment of osteoporosis can have implications for more invasive dental procedures like extractions. Generally, patients who have taken oral bisphosphonate for less than 4 years and have no clinical risk factors do not require any alteration or delay in the provision of routine dental care.28 On the other hand, patients who need invasive dental procedures should be carefully evaluated for the risk of osteonecrosis of the jaw.

Because asthma is often seen in patients with Crohn’s disease, the use of ultrasonic scalers may be inadvisable.29 Additionally, many asthma medications can cause oral side effects, such as xerostomia and increased caries risk. Patients should be educated on the side effects, the potential for increased caries risk, and self-care practices that can help mitigate that risk, such as rinsing the mouth immediately after using an inhaler.

Some patients with Crohn’s disease are prescribed blood thinners to limit the risk of inappropriate blood clotting. Several of these medications require patients to regularly undergo coagulation testing, with the international normalized ratio (INR) most often used. The ideal INR values for patients taking blood thinners is 2.0 to 3.0.

Adults, adolescents, and children with Crohn’s disease are more likely to experience severe oral disease than their counterparts. Studies have shown an increased prevalence of periodontal diseases and caries among those with Crohn’s disease.30,31 Patients with Crohn’s disease, despite showing minimal biofilm accumulation, tend to have high decayed, missing, filled teeth scores, are likely to have bleeding on probing at more sites, and also display a tendency toward deep periodontal pockets.28 Thus, clinicians should execute careful, regular monitoring of caries and periodontal risks to help patients with Crohn’s disease maintain optimal oral health.

CONCLUSION

Oral health professionals will most likely encounter patients with Crohn’s disease in the dental setting. Their treatment likely requires a collaborative efforts that include both dental providers and primary care physicians/gastroenterologists. Because manifestations of Crohn’s disease may appear in the mouth before intestinal signs are noted, oral health professionals should be aware of the disease’s signs and symptoms so a referral for definitive diagnosis can be made.

While some patients with Crohn’s disease may present with minimal or no complications, others may experience problems that significantly impact the provision of oral health care. The careful review of patients’ medical histories, medication regimens, and dietary habits is necessary to create personalized and safe oral health care plans. Emphasis should be placed on patient education regarding the specific oral-systemic health implications for optimal oral health.

References

- Peery AF, Dellon ES, Lund J, et al. Burden of gastrointestinal disease in the United States: 2012 update. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:1179–1187.

- Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America. The FactsAbout Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Available at: ccfa.org/assets/pdfs/ibdfactbook.pdf. Accessed February 17, 2016.

- Loftus EV. Clinical epidemiology of inflammatory bowel diseases: Incidence, prevalence and environmental influences. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1504–1517.

- Hou JK, Abraham B, El-Serag H. Dietary intake and risk of developing inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review of the literature. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:563–573.

- Ko Y, Butcher, R, Leong RW. Epidemiological studies of migration and environmental risk factors in the inflammatory bowel diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:1238–1247.

- Kappelman MD, Moore KR, Allen JK, Cook SF. Recent trends in the prevalence of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in a commercially insured US population. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;58:519–525.

- Baumgart DC, Sandborn WJ. Crohn’s disease. Lancet.2012;380:1590–1605.

- Baumgart DC, Sandborn WJ. Inflammatory bowel disease: Clinical aspects and established and evolving therapies. Lancet. 2007;369:1641–1657.

- Schulfer A, Blaser MJ. Risks of antibiotic exposures early in life on the developing microbiome. PLoS Pathogens. 2015;11:1–6.

- Ham M, Longhi MS, Lahiff C, Cheifetz A, Robson S,Moss AC. Vitamin D levels in a adults with Crohn’s disease are responsive to disease activity and treatment. Inflamm Bowl Dis. 2014;20:856–860.

- Alawi F. An update on granulomatous diseases ofthe oral tissues. Dent Clin North Am. 2013;57:657–671.

- Katsanos KH, Torres J, Roda G, Brygo A, Delaporte E,Colombel JF. Review article: Non-malignant oral manifestations in inflammatory bowel diseases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;42:40–60.

- Ormond M, Sanderson JD, Escudier M. Disorders ofthe mouth. Medicine. 2015;43:187–191.

- Wilkins T, Jarvis K, Patel J. Diagnosis andmanagement of Crohn’s disease. Am Fam Physician. 2011;84:1365–1375.

- Richards CJ. Pathological considerations in Crohn’s disease. In: Rajesh A, Sinha R, eds. Crohn’s Disease: Current Concepts. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2015:11–21.

- Ye Z, Lin Y, Cao Q, He Y, Xue L. Granulomas as the most useful histopathological feature in distinguishing between Crohn’s disease and intestinal tuberculosis in endoscopic biopsy specimens. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:1–9.

- Neville BW. Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology.St. Louis: Elsevier/Saunders; 2009:968.

- Scully C, Cochran KM, Russell RI, et al. Crohn’s disease of the mouth: An indicator of intestinal involvement. Gut. 1982;23:198–201.

- Rowland M, Fleming P, Bourke B. Looking in the mouth for Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:332–337.

- Tilakaratne WM, Freysdottir J, Fortune F. Orofacial granulomatosis: Review on aetiology and pathogenesis. J Oral Pathol Med. 2008:37:191–195.

- Ejeil A-L, Thomas A, Mercier S, Moreau N.Unusual gingival swelling in a 4-year old child. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2014;118:627–631.

- Lazzarini M, Martelossi S, Cont G, et al. Orofacial granulomatosis in children: Think about Crohn’s disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2015;47:338–341.

- DeFelice KM, Katzka DA, Raffals LE. Crohn’s disease of the esophagus: Clinical features and treatment outcomes in the biologic era. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21:2106–2113.

- Dignass A, VanAssche G, Lindsay JO, et al. The second European evidence-based consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn’s disease: current management. J Crohns Colitis. 2010;4:28–62.

- Zachos M, Tondeur M, Griffiths AM. Enteral nutritional therapy for induction of remission in Crohn’s disease. Cochrane Database Sys Rev. 2007;1:CD000542.

- Quijano D, Rodriguez M. Topical cortico steroids in recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Systematic review. Acta Otorrinolaringol Esp. 2008;59:298–307.

- Beltran B. Extrainitestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease: Do they influence treatment and outcome? World J Gastroenterol. 2011:17:2702–2707.

- Ruggiero SL, Dodson TB, Fantasia J, et al.American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons position paper on medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw—2014 update. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014;72:1938–1956.

- Bateman ED, Hurd SS, Barnes PJ, Bousquet J, et al. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention: GINA executive summary. Eur Respir J. 2008;31:143–178.

- Koutsochiristou V, Zellos A, Dimakou K, et al. Dental caries and periodontal diseases in children and adults with inflammatory bowel disease: A case-control study. Inflamm Bowel Dis.2015;21;1839–1846.

- Brito F, deBarros FC, Zaltman C, et al. Prevalence of periodontitis and DMFT index in patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. J Clin Periodontol. 2008;35:555–560.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. March 2016;14(03):44–47.

REACHING A DEFINITIVE DIAGNOSIS

REACHING A DEFINITIVE DIAGNOSIS