RUSSELL KIGHTLEY/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

RUSSELL KIGHTLEY/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

Recognize the Signs

Successful strategies for addressing eating disorders with patients.

Eating disorders (EDs) are psychiatric illnesses with psychological, behavioral, and physiological manifestations. Often accompanied by feelings of angst about weight and body image, EDs cause serious disturbances in eating behavior, including excessive undereating or overeating.1,2 An estimated 25 million Americans experience EDs, which have the highest mortality rate of all psychiatric illnesses.3 While most common among adolescent girls, current data show that the prevalence is also rising among adolescent boys.3 EDs affect people of all ethnicities, ages, and socioeconomic statuses.3

EATING DISORDER CLASSIFICATIONS

According to the National Comorbidity Survey Replication, the lifetime prevalence of EDs in the United States ranges from 0.6% to 4.5%.4 The most common types of EDs are anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating disorder. The fifth edition of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V) lists the specific criteria for the diagnosis of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and other specified or unspecified feeding or eating disorders. However, many individuals present with subthreshold EDs that do not meet the DSM-V’s strict diagnostic criteria, but result in disordered eating.4,5

Anorexia nervosa is defined as a restriction of energy intake leading to low body weight. People with anorexia have an intense fear of gaining weight and will restrict eating to an unhealthy level. Anorexia nervosa can include binge eating and purging behaviors, such as self-induced vomiting and the misuse of laxatives, diuretics, or enemas.1

Bulimia nervosa is classified as recurrent patterns of binge eating followed by compensatory behavior to prevent weight gain, such as self-induced vomiting; misuse of laxatives, diuretics, and enemas; fasting; and excessive exercise.1,5 Individuals with bulimia nervosa may be at, above, or below their normal weight, whereas those with anorexia nervosa are underweight.1,6

Binge eating disorder is the most common ED5 and involves recurrent episodes of overeating in the absence of compensatory behaviors, such as purging.1 Binge eating is the consumption of excessive amounts of food within a short period of time (eg, 2 hours) along with a sense of impaired control. Individuals with binge eating disorder often experience negative emotions regarding the binging, such as guilt, embarrassment, or depression.1

RELATED FACTORS

The signs and symptoms of disordered eating may appear similar to other health conditions, such as celiac disease, irritable bowel syndrome, Addison’s disease, and hyperthyroidism,

as well as the post-operative results of bariatric surgery. Careful attention to medical history intake and patient dialogue are key to ascertaining the presence of an ED.

Substance abuse, obsessive-compulsive behaviors, and personality disorders are common comorbidities of EDs.6 Biological, social, and psychological factors all influence the development of EDs. Genetic tendencies, unrealistic body image ideal, lack of self-esteem, and comorbidities, such as anxiety and depression, may play a role in EDs.7,8 Individuals with ED often experience a great deal of shame and guilt, and they may avoid disclosure until obvious manifestations of the ED force the issue. ED prognosis can be

improved with early screening, detection, and intervention.8

According to the American Diabetes Association, women and girls with type 1 diabetes are three times more likely to develop EDs than those who don’t have type 1 diabetes.9

Individuals with type 1 diabetes can restrict their insulin intake in order to prevent weight gain or to produce weight loss, a condition called diabulimia. When insulin is reduced, the

body is unable to turn food into energy, leading to breakdown of fat and muscle tissue. Excess sugar is excreted through frequent urination, and dehydration and dramatic weight

loss are the result.

TREATMENT

Individuals with ED can undergo inpatient or outpatient treatment with a health care team that often consists of counselors, physicians, nurses, and dietitians. Using a whole body approach to treat EDs is essential for effective management and successful outcomes.10 Close communication between team members is critical for seamless and successful intervention. Unfortunately, because oral health professionals are not part of the ED recovery team, many individuals undergoing treatment lack dental care and often experience irreversible destruction of their dentition. Enamel erosion, caries, and periodontal diseases can often be circumvented in this patient population with early, consistent preventive care.7

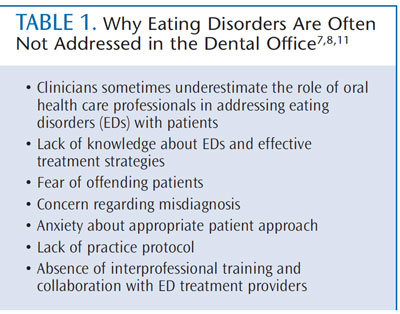

While the results of EDs on the oral cavity have been discussed in the literature since the 1980s, studies show that oral health care professionals generally lack solid understanding of how to discuss and provide appropriate treatment when an ED is recognized.7 Table 1 lists the reasons that oral health care professionals may fail to address the signs of EDs.7,8,11

PATIENT APPROACH

According to Beth A. Mayer, LICSW, and Lindsay Brady, LICSW, of the Multi-Service Eating Disorders Association (MEDA) in Newton, Mass, individuals with eating disorders are often very reticent about their behaviors and they frequently carry a great deal of shame regarding their symptoms. They advise that patients should be approached in a sensitive, but direct, manner. Oral health care professionals have a responsibility to investigate the origin of the pattern of disease/destruction noted in a patient and to document observations and recommendations, as well as the patient’s response. MEDA recommends that oral health care professionals ask the following questions when an ED is suspected:10

- Can you tell me about any behaviors you may currently engage in that could be having this effect on your mouth (or health)?

- Are you currently seeking professionalhelp related to these behaviors?

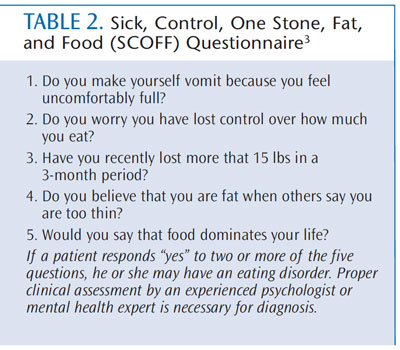

Oral health care professionals can implement screening for EDs when appropriate. British researchers Morgan, Reid, and Lacy created the sick, control, one stone (14 lbs), fat,

and food (SCOFF) questionnaire, a five-question tool used to screen patients for anorexia and bulimia nervosa (Table 2).3 It was developed in 1999 and can be easily administered

in any health care setting.3 While there is no current standard for ED screening, the SCOFF questionnaire can be worked into routine medical history intake along with caries, periodontal, and oral cancer risk assessments.10 EDs do not always manifest intraorally.

Careful attention to medical history intake and patient dialogue are key to understanding patients’ conditions and needs.9 MEDA also recommends against counseling patients. Concern should be expressed, as well as recommendations to treat the oral problems, but referral for counseling should be given only if the patient is interested. Oral health care professionals serve as clinical investigators and supportive coaches.10 They should never diagnose patients or try to shame them into treatment. Oral health care professionals should treat these patients normally, remain supportive of their oral health needs, and provide appropriate resources when requested.10

MINOR PATIENTS

The Massachusetts Eating Disorders Collaborative suggests that in the case of a minor, the parent or guardian should be present when the oral health care professional shares his or her concerns and findings. However, if abuse is suspected, clinicians may need to communicate with the child’s pediatrician or primary care provider. Oral health care professionals need to work within the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act and obtain a medical information release from the parent. A signed release should ideally include the patient’s primary care physician. If so, the oral health care professional can speak directly to the physician. This collaborative care may improve recovery results. It is critical to know the state laws regarding collaborative consultation. Some states may allow collaboration between health providers when the well-being of the patient is at stake without the

need for a signed release.12

The Massachusetts Eating Disorders Collaborative suggests adding the following questions to the medical history intake:12

- Do you have an eating disorder or history of an eating disorder?

- Do you purge or have a history of purging?Frequency per day ______, week ______, month ______.

A confidential watermark should be added to each page of the patient medical history form to encourage patients to share this type of sensitive health information.12

ORAL HEALTH CONSIDERATIONS

Bulimia nervosa has significant consequences on the oral cavity. Enamel erosion, xerostomia, erythema of the pharynx, changes in occlusion, and palatal bruising can be indicators of bulimic behavior. Enamel erosion typically results in lesions that are shallow and wide. Only preventive, provisional, or temporary treatment should be provided until the causative condition is determined and treated, with the exception of active caries and severe dental erosion, which require immediate restorative care.13 Aside from restorative treatment options, oral health care professionals should carefully weigh risk factors, such as binging and purging practices, as well as the individual’s emotional well-being. Collaboration with members of the ED treatment team can assist with timing and extent of restorative and preventive care.14

EDs are often accompanied by comorbidities that may require the use of medications that cause hyposalivation or xerostomia. Chronic xerostomia increases the acidic environment

of the oral cavity, resulting in enamel destruction and the promotion of plaque formation that can increase periodontal inflammation. Additionally, comorbidities can interfere with an individual’s ability or motivation to perform oral hygiene and seek routine preventive care.15 All health care providers must be sensitive to their patients’ needs and

cues, as the manifestations of ED can vary depending on the category of diagnosis and accompanying comorbidities.10

RECOMMENDATIONS

Patients with ED are at high risk of caries, thus, evidence-based clinical recommendations for professionally applied topical fluoride must be implemented. Application of 5% sodium fluoride varnish or 4-minute tray delivery of 2% neutral sodium gel are recommended for remineralization of enamel, and should be applied every 3 months until the patient is no longer at high risk for caries. Patients with compromised enamel, but reduced caries risk, still require fluoride treatment at least semiannually.13,16

The use of 1.1% neutral sodium fluoride gel in custom-made trays for 5 minutes daily, or twice daily brushing with a prescription fluoride toothpaste can help reduce caries risk.8 Patients at high caries risk require increased levels of protective fluoride to counteract the acid attacks of regular vomiting, xerostomia, and/or neglected biofilm.13,16

Patients should be advised to rinse with 1 teaspoon of baking soda mixed with 8 ounces of water after vomiting to neutralize the acid. If baking soda is not available, simply rinsing with water is beneficial.8,15 Patients should not brush their teeth for at least an hour after vomiting because the enamel is softened by stomach acid.8,15 An over-the-counter 0.05% fluoride mouthrinse can be recommended to help reduce enamel loss, but this is not sufficient to support remineralization in patients at high caries risk.8,13,16

During dental appointments, abrasive products should be avoided. Polishing of the enamel is contraindicated unless stain is obvious.8,17 Intraoral photography should be used

to document the state of the oral cavity for future comparison of damage or tissue repair.8

FINAL THOUGHTS

Oral health care professionals can provide the link patients need to begin recovery from these potentially life-threatening illnesses through careful screening, patient rapport, oral care, and referral. Although individuals with EDs may take years to recover, clinicians must remain judgment-free and supportive of the individual’s efforts to seek oral health care.

Remaining positive and reaching out to collaborative

providers on the treatment team may

promote more effective care and encourage

improved overall health outcomes.

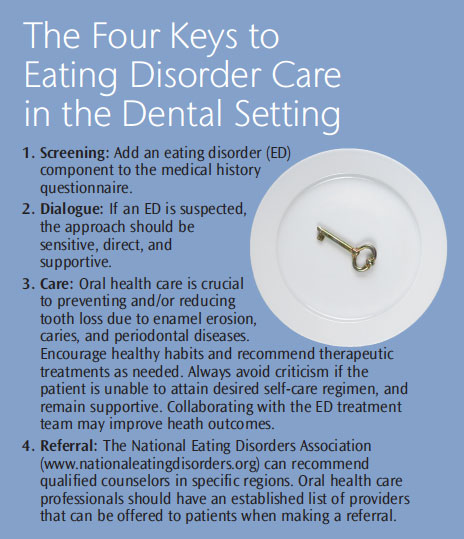

The Four Keys to Eating Disorder Care in the Dental Setting

- Screening: Add an eating disorder (ED) component to the medical history questionnaire.

- Dialogue: If an ED is suspected, the approach should be sensitive, direct, and supportive.

- Care: Oral health care is crucial to preventing and/or reducing tooth loss due to enamel erosion, caries, and periodontal diseases. Encourage healthy habits and recommend therapeutic treatments as needed. Always avoid criticism if the patient is unable to attain desired self-care regimen, and remain supportive. Collaborating with the ED treatment team may improve heath outcomes.

- Referral: The National Eating Disorders Association (www.nationaleatingdisorders.org) can recommend qualified counselors in specific regions. Oral health care professionals should have an established list of providers that can be offered to patients when making a referral.

REFERENCES

-

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V). Arlington, Va: American Psychiatric Publishers; 2013:307.1–307.51,307.59, 307.50.

- National Eating Disorder Association. Available at: www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/general-information. Accessed May 30, 2013.

- Morgan J, Reid F, Lacy JH. The SCOFF Questions. Western Journal of Medicine. 2006;172:164–165.

- Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG,Jr, Kessler RC. The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:348–358.

- Bulik C. Midlife Eating Disorders. New York: Walker Publishing; 2013.

- Pritts SD, Susman J. Diagnosis of eating disorders in primary care. Am Fam Physician. 2003;67:297–304.

- DeBate RD, Tedesco LA, Kerschbaum WE. Knowledge of oral and physical manifestations of anorexia and bulimia nervosa among dentists and dental hygienists. J Dent Educ. 2005;69:346–354.

- Burkhart N, Roberts M, Alexander M, Dodds A. Communicating effectively with patients suspected of having bulimia nervosa. J Am Dent Assoc. 2005;136:1130–1137.

- Ozier AD, Henry BW, American Dietetic Association. Position of the American Dietetic Association: nutrition intervention in the treatment of eating disorders. J Am Diet Assoc. 2011;111:1236–1241.

- Multi-service Eating Disorders Association. Available at: www.medainc.org. Accessed May 30, 2013.

- Debate RD, Tedesco LA. Increasing dentists’ capacity for secondary prevention of eating disorders: identification of training, network, and professional contingencies. J Dent Educ. 2006;70:1066–1075.

- Eating Disorders Collaborative MA. Available at: www.eatingdisorderscollaborativema.org. Accessed May 30, 2013.

- American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs. Professionally applied topical fluoride: evidence-based clinical recommendations. J Am Dent Assoc, 2006;137:1151–1159.

- Gurenlian JR. Eating disorders. J Dent Hyg. 2002;76:219–234.

- Stegman C, Slim L. Recognizing and Managing ED in Dental Patients, Available at: www.media.dentalcare.com/media/en-us/education/ce93/ce93.pdf. Accessed May 30, 2013.

- Jenson L, Budenz AW, Featherstone JDB, Ramos-Gomez FJ, Spolsky VW, Young DA. Clinical protocol for caries management by risk assessment. Journal of the California Dental Association. 2007;35(10):714–723.

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association position paper on polishing. American Dental Hygienists’ Association. Available at: www.adha.org/resourcesdocs/7115_Prophylaxis_Postion_Paper.pdf Accessed May 30, 2013.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. July 2013; 11(7): 24, 26, 28.