HEADER IMAGE: GJLP / SCIENCE SOURCE

HEADER IMAGE: GJLP / SCIENCE SOURCE

Providing Care to Patients with Parkinson’s Disease

Dental hygienists can help improve these patients’ oral health, comfort, and function, as well as their quality of life.

This course was published in the March 2014 issue and expires March 31, 2017. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Describe the clinical signs and symptoms of Parkinson’s disease (PD).

- Identify the prevalence of PD.

- Detail treatment considerations for providing care to patients with PD.

- Discuss how dental hygienists can help patients with PD improve their oral self-care regimens.

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a chronic, progressive, degenerative disorder of the central nervous system, characterized by a decrease in spontaneous movements, gait difficulty, postural instability, rigidity, and tremors. The disease is caused by the degeneration of the pigmented neurons in the substantia nigra of the brain, resulting in decreased availability of the neurotransmitter dopamine (Figure 1)—a chemical that transmits messages to the cerebrum that controls movement and coordination. As PD progresses, the amount of dopamine produced in the brain decreases, leaving individuals unable to control their body movements.1–4

A combination of genetic and environmental factors may affect PD; however, recent scientific advances point toward genetic mutations and mitochondrial impairment as the most likely etiology of this disease. Other possible causes include stroke, head injury, and brain tumors.5–7 At present, there is no standard of care for treating patients with PD, and there is no cure. Treatment approaches include medication; surgical therapy; lifestyle modifications, such as exercise and rest; physical therapy; occupational therapy; and speech therapy. Individualized care is directed at treating the most debilitating symptoms.8,9

PREVALENCE

In 2010, roughly 630,000 Americans were diagnosed with PD, and this statistic is expected to double by 2040, as the number of older adults in the United States continues to grow.10 Men are one and a half times more likely to develop PD than women.2,3 PD is most prevalent among adults older than 60; however, the American Parkinson’s Disease Association National Young Onset Center notes that 10% to 20% of PD cases are diagnosed in individuals younger than 50.11 Prevalence rates for PD are often underestimated because symptoms may present for years before treatment is sought and a diagnosis is made.10

The needs of an aging population require dental hygienists to be competent in the management of medically compromised patients. Clinicians will be better prepared to effectively treat patients with PD by learning more about the condition’s symptoms, etiology, pharmacologic management, and clinical presentations. Dental hygienists also need to grow their knowledge on how to provide services to patients with disabilities, as this population is increasingly accessing oral health care in private practice settings.

TREATMENT CONSIDERATIONS IN THE DENTAL SETTING

When planning dental treatment for patients with PD, dental hygienists must be cognizant of the severity of their health status. Some patients may have very slight PD and need no treatment alterations, while others may have more severe PD and need modifications, such as bite blocks, to compensate for the lack of oral muscular control.3

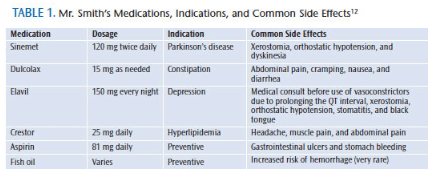

Understanding the medications that patients with PD are taking is important to providing safe and effective care. Clinicians need to pay close attention to contraindications and potential drug interactions.12 Sinemet—a combination of the drugs cardidopa and levodopa (Figure 2)—is one of the most potent and common therapies for PD. Patients who have been taking levodopa or sinemet for several years may develop dyskinesia—the impairment of voluntary movements resulting in tic-like involuntary movements. Dyskinesia often affects the jaw, which can create difficulty in safely accessing the patient’s mouth. Also, the dyskinetic movements may lead to bruxism.3 Dopamine agonists, anticholinergic drugs, monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), and catechol-O-methyl transferase inhibitors are some of the other medications used to treat PD.3,4,9

Clinicians may need to use soft restraints on patients with PD to help contain tremors and provide support during dental treatment. This population often experiences dysphagia, which affects the ability to eat, drink, and relax. The presence of dysphagia raises the risk of silent aspiration—when food, liquids, or stomach contents flow into the lungs—which can lead to pneumonia.13 Salivary dysfunction is common and can result in both excessive salivation (sialorrhea) and xerostomia. Sialorrhea manifests as excessive drooling, which can cause dysphagia, often resulting in sudden coughing and choking.

Patients with PD should receive dietary counseling if they are experiencing xerostomia, to reduce their caries risk. Also, the use of prescription fluoride and in-office topical fluoride treatments may be indicated when the risk of caries is elevated. Artificial salivary lubrication products should be recommended to mitigate the symptoms of xerostomia. Although plaque biofilm management is important in this population, chlorhexidine gluconate mouthrinses are contraindicated due to patients’ decreased ability to expectorate, thus there is increased risk for ingestion. This population needs more frequent recare intervals, as multiple short appointments will be more effective.3,14,15

Dental hygienists should be aware of what symptoms patients with PD have experienced in the past when receiving dental treatment, such as orthostatic hypotension, excessive saliva due to problems swallowing, fear/anxiety, memory difficulties, stooped posture, instability, freezing (gait), tremors, and rigidity.

PRACTICAL TIPS FOR EFFECTIVE ORAL SELF-CARE

Nearly half of all people with PD have difficulty with their daily oral hygiene regimens.3 Dental hygienists should provide patients with explicit instructions to help them maintain good oral hygiene. These instructions should be provided in both written and verbal forms to patients and caregivers.15

Dental hygienists should recommend that patients sit down to brush and floss. This not only reduces the risk of falling, but also helps conserve energy. A shower or commode chair works well for this. Patients can prop their elbows up on the bathroom sink if their shoulders tire easily.16

Patients with PD?may be better served with a power toothbrush or manual toothbrush specially designed for those with limited dexterity. Oral devices can be made easier to hold by attaching a tennis ball on the end of the handle. A dental water jet to provide at-home irrigation may also be helpful. Floss threaders, floss holders, other adjuncts used with traditional floss, and interdental brushes may improve the efficacy of flossing, as well as compliance.

CASE STUDY

Mr. Smith*, a 77-year-old white man with PD, presented for treatment in a private general dental practice with his vital signs within the normal range. He was a retired military veteran and General Motors plant worker. Diagnosed with PD at age 63, Mr. Smith was taking Sinemet (Table 1 provides an overview of his medication usage). He was diagnosed with high cholesterol at age 68 and depression at 71. Mr. Smith experienced a concussion due to a fall at age 69, and he had both of his knees replaced at age 70. He had penicillin and latex allergies, which resulted in hives surfacing around the areas touched by latex gloves.

*The patient’s name and health history details have been changed to protect his privacy.

Mr. Smith had many of the typical symptoms experienced by patients with PD, including shuffled gait. Due to the decrease in muscle movement and coordination caused by PD, he used a cane to walk and moved fairly slowly (bradykinesia). Mr. Smith had decreased range of motion in relation to the stretching of his muscles (rigidity) and lacked facial expression (masking).3,13 These findings, in addition to the loss of fine muscle control in the oral cavity, temporomandibular joint dysfunction, and impaired vocalization (dysarthria), are common oral motor and sensorimotor impairments associated with PD.13

Mr. Smith’s knee replacements required antibiotic prophylaxis prior to beginning any dental treatment. His orthopedic surgeon prescribed 600 mg of clindamycin, due to his penicillin allergy, to be taken 1 hour before beginning dental treatment. Due to Mr. Smith’s latex allergy, the dental hygienists used nitrile gloves and nonlatex dental equipment and supplies. Orthostatic hypotension was a side effect of two of the medications he was taking. This, combined with his diminished physical state, required close monitoring when he rose from and exited the dental chair.

Extraorally, his tremors were challenging for the dental hygienist to manage. Accommodating Mr. Smith required exceptional patient management expertise and additional treatment time. The need for longer appointments sometimes makes dental practices hesitant to accept individuals with PD as patients. Clinicians must remember that patients with disabilities have a right to access oral health care services, and any attempt to avoid providing care (ie, referral to a specialist for conditions typically treated in a general practice) may be considered discrimination under the Americans with Disabilities Act.17

The Oral Health Related Quality of Life (OHQoL) instrument was used to assess Mr. Smith’s quality of life and how it influenced his oral health.18 Transportation was identified as a barrier to receiving health care because he could not drive, but his wife was willing to bring him to appointments. Mr. Smith perceived his general health as worse than most of his peers because of his PD diagnosis, mobility complications, and medication regimen for constipation, high cholesterol, and depression. He attempted to influence his mobility by performing some type of physical activity daily to maintain mobility and independence. Mr. Smith’s mobility greatly influenced decisions about his medical and dental care. He could do most things for himself, but only for short periods of time. He reported his muscles quickly becoming tired and extremely stiff. He depended heavily on his wife to help with his activities of daily living.

Mr. Smith’s OHQoL assessment was fair. He looked forward to seeing his four children and 10 grandchildren whenever possible. He was actively seeking health care and wanted to be in the best health possible. He was struggling with depression, which often accompanies PD.2–4 Mr. Smith reported feeling upset and angered about how PD interfered with his life. He and his wife also experienced stress due to the financial hardship of his illness. Although Mr. Smith had stress in his life, he was motivated to improve his health and, in particular, his oral health with lifestyle changes—including healthy eating and practicing exercises recommended by his physical therapist.

Mr. Smith’s main oral health complaints were that his maxillary removable partial denture did not fit comfortably and extrinsic stain. He reported no pain aside from occasional cold sensitivity. Mr. Smith experienced sialorrhea, which caused excessive drooling, and dysphagia due to the decreased efficacy of his swallowing muscles. He also presented with fractured teeth and significant attrition, both signs of bruxism.

The American Dental Association Caries Management by Risk Assessment form was utilized to assess Mr. Smith’s caries risk and to make recommendations for interventions. Mr. Smith presented with recurrent interproximal and coronal caries. His saliva flow was below normal, and his salivary pH was 6.2. Mr. Smith’s self-care regimen consisted of brushing twice daily most of the time, but at least once daily, with no interdental aids. His last dental exam and prophylaxis was 15 years ago. His recommended maintenance at that time was once every 6 months. His infrequent care was due to financial constraints.

The patient presented with xerostomia, dental caries, and chronic periodontitis (Table 2 summarizes Mr. Smith’s initial oral health status). The caries was most likely caused by his lack of salivary flow due to medication-induced xerostomia and his inability to effectively swallow. Overall, Mr. Smith’s decreased manual dexterity and control of body mobility due to PD put his oral health at elevated risk for periodontal diseases and caries.

Mr. Smith underwent periodontal scaling and root planing in all four quadrants. At the 6-week re-evaluation appointment, his periodontal health had stabilized, his partial denture fit properly, and the caries lesions were removed and restorations placed. His short-term goals were to employ a power toothbrush twice daily to remove biofilm; utilize a floss handle to remove interproximal biofilm once daily; and apply prescription-strength fluoride toothpaste once daily to reduce caries risk. His long-term goals were to maintain his current periodontal status and to prevent new caries lesions. The dental hygienist discussed the importance of continued 3-month professional periodontal maintenance therapy and consistent oral self-care to achieve these long-term goals.

![]() RESOURCES FOR PATIENTS WITH PARKINSON’S DISEASE

RESOURCES FOR PATIENTS WITH PARKINSON’S DISEASE

By keeping up to date on the available resources, dental hygienists can link patients to valuable support and services. Clinicians must be ready to assist individuals in learning more about PD; locating support groups; identifying resources to overcome barriers, such a transportation and lack of financial constraints; and finding resources to help individuals live independently. Mr. Smith was fortunate to live near the Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorder Center at the University of Kansas in Kansas City, Kan. The center is recognized internationally for its expertise in the diagnosis, treatment, and research of PD. It offers deep brain stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus, globus pallidus, and thalamus; specialized speech, swallowing, occupational, and physical therapy; and a variety of social services.

Table 3 provides a comprehensive list of national resources for PD. This table should serve as a starting point for dental hygienists who are trying to identify resources for patients and caregivers. Many of the organizations in the table have local and/or regional branches.

CONCLUSION

Treating patients with PD provides dental hygienists opportunities to expand the provision of oral health care to a population that often lacks access. For patients living with PD, dental hygienists play an important role in enhancing oral comfort and quality of life through the development of meaningful health promotion and disease prevention strategies.

Current knowledge about PD symptoms, etiology, medications, clinical presentations, how to modify treatment based on the dental hygiene process of care, and available resources will aid dental hygienists in providing optimal care. Patients with PD should feel confident that dental hygienists will use evidence-based information to design a care plan that meets their individual needs.

REFERENCES

- American Parkinson Disease Association. Basic info about PD. Available at:?apdaparkinson.org/publications-information/basic-info-about-pd. Accessed February 21, 2014.

- A.D.A.M. Medical Encyclopedia. Parkinson’s Disease. Available at: nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/000755.htm. Accessed February 21, 2014.

- Parkinson’s Disease Foundation. Understanding Parkinson’s. Available at: pdf.org/understanding_pd. Accessed February 21, 2014.

- Golbe LI, Mark MH, Sage JI. Parkinson’s Disease Handbook—A Guide for Patients and Their Families. New Brunswick, NJ: American Parkinson Disease Association Inc; 2009.

- Schapira AH. Etiology of Parkinson’s disease. Neurology. 2006;66(Suppl 10):S10–23.

- Martin I, Dawson VL, Dawson TM. Recent advances in the genetics of Parkinson’s disease. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2011;12:301–325.

- Singleton AB, Farrer MJ, Bonifati V. The genetics of Parkinson’s disease: progress and therapeutic implications. Mov Disord. 2013;28:14–23.

- Oberdorf J, Schmidt P. Improving Care for People with Parkinson’s Disease. Miami: National Parkinson Foundation; 2010.

- National Parkinson’s Foundation. How is PD treated? Available at: parkinson.org/ parkinson-s-disease.aspx. Accessed February 20, 2014.

- Kowal SL, Dall TM, Chakrabarti R, Storm MV, Jain A. The current and projected economic burden of Parkinson’s disease in the United States. Mov Disord. 2013;28:311–318.

- American Parkinson Disease Association-National Young Onset Center. What you should know about early onset Parkinson’s disease. Available at: youngparkinsons.org/what-you-should-know-about-early-onset-parkinsons-disease/symptoms/information. Accessed February 21, 2014.

- Wynn R, Meiller T, Crossley H. Drug Information Handbook for Dentistry. 16th ed. Hudson, Ohio: Lexi-Comp; 2010-2011.

- Huber MA. Parkinson’s Disease and Oral Health Educational Supplement #7. Staten Island, NY: American Parkinson Disease Association Inc; 2007.

- Little JW, Falace DA, Miller CS, Rhodus NL. Dental Management of the Medically Compromised Patient. St. Louis: Elsevier Mosby; 2013.

- Friedlander AH, Mahler M, Norman KM, Ettinger RL. Parkinson’s disease: systemic and orofacial manifestations, medical and dental management. J Am Dent Assoc. 2009;140:658–669.

- Cianci H, Cloete L, Gardner J, Trail M, Wichmann R. Activities of Daily Living: Practical Pointers for Parkinson’s Disease. 3rd ed. Miami: National Parkinson Foundation; 2006.

- United States Department of Justice Civil Rights Division. Information and Technical Assistance on the Americans with Disabilities Act. Available at: ada.gov. Accessed February 21, 2014.

- Williams KB, Gadbury-Amyot CC, Bray KK, Manne D, Collins P. Oral health-related quality of life: a model for dental hygiene. J Dent Hyg. 1998;72:19–26.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. March 2014;12(3):49–53.

FEATURED IMAGE: This colored computed-tomography scan shows a horizontal view of the brain of a patient with Parkinson’s disease. The disease has caused the ventricles to increase in size, as the brain tissue has lost density.

RESOURCES FOR PATIENTS WITH PARKINSON’S DISEASE

RESOURCES FOR PATIENTS WITH PARKINSON’S DISEASE