YAKOBCHUKOLENA / ISTOCK / GETTY IMAGES PLUS

YAKOBCHUKOLENA / ISTOCK / GETTY IMAGES PLUS

Promoting Healthy Aging in the Dental Setting

Integrating tailored health promotion and preventive interventions, such as risk assessment for falls, with the provision of oral healthcare may facilitate a pathway to active, healthy aging.

This course was published in the June 2022 issue and expires June 2025. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Discuss the impact of population aging.

- Identify programs that incorporate systemic health screening into the dental setting and explain the results.

- List the stages of behavior change.

Dental hygienists are recognized as health promotion and disease prevention specialists, partly due to the specialized education and training they receive as students. This education is expanded upon with clinical experience in the workforce. Dental hygienists are highly skilled members of the dental team. They are well-positioned to act as portals to interdisciplinary healthcare referrals when indicated. This provides the dental hygiene clinician with the opportunity to provide preventive, supportive, patient-centered healthcare. In particular, as the United States population continues to age, dental hygienists may be able to promote active and healthy aging. As such, the dental hygiene profession may want to expand its scope of practice to include assessments for the promotion of active and healthy aging.

Population Aging—A Global Occurrence

By 2050, the number of older adults will exceed the number of young individuals worldwide. Referred to as population aging, this development is without precedent in human history.1 Musculoskeletal injuries, such as hip, vertebral, or distal forearm fractures, present significant health problems for aging adults. In 2010, the annual rate of hospitalization for musculoskeletal conditions ranged from 3% among those between the ages of 65 and 74, 5% among individuals ages 75 to 84, and 8% in those 85 and older.

Older women are more likely than older men to be hospitalized for musculoskeletal conditions.2 Each year, 2% of noninstitutionalized individuals ages 65 and older report experiencing a fracture and 2% experience a dislocation or sprain.2 Fractures due to a fall are even more frequent among nursing-home residents. People with musculoskeletal conditions often have physical limitations that impede their abilities to perform routine oral healthcare activities, ultimately, contributing to increased healthcare needs.2

Person-Centered Oral Healthcare

In the US, more adults tend to see their dentist each year than their physician.3 Patients regularly visit an oral health professional for preventive care, but may see a physician only when ill. Often patients develop a long-term relationship with their oral health professionals. These practice patterns provide an opportunity in the dental setting to expand access to or facilitate delivery of preventive healthcare services that could promote and sustain healthy aging.

Given that the incidence of chronic disease and the emergence of other health issues increase over the lifespan, early identification of health issues provides an opportunity for those at risk to benefit from primary prevention activities. These may include initiating behavior changes that could modify their risk factors (eg, dietary modifications, increased physical activity, pharmacological therapy); delaying disease onset; or controlling disease severity. Studies have documented patients’ willingness to undergo screening for health conditions as part of a dental visit to aid in prevention of diseases, assist in controlling disease progression, and prevent complications.4

A growing body of research is documenting the feasibility, acceptability, and value of integrating screening for various health conditions, such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and obesity, as part of oral health treatment services and community outreach activities.3–6 Physicians have acknowledged the utility of this multidisciplinary approach as a means of identifying individuals at risk for adverse health events.3,5 In 2004, Columbia University, College of Dental Medicine and its partners instituted the ElderSmile program.5 This program integrated health screenings with oral health outreach activities at a community senior center, which strongly demonstrated the public health value of this integrated service. The program goals were to improve access to and delivery of oral healthcare for older adults and establish and operate a network of prevention centers.6 Health screenings delivered through ElderSmile identified older adults with undiagnosed hypertension (25%) and diabetes (8%), as well as individuals whose diagnosed hypertension (38%) and diabetes (38%) were not under control.6 The ElderSmile program is a replicable model for community-based oral and general health screening.5,6

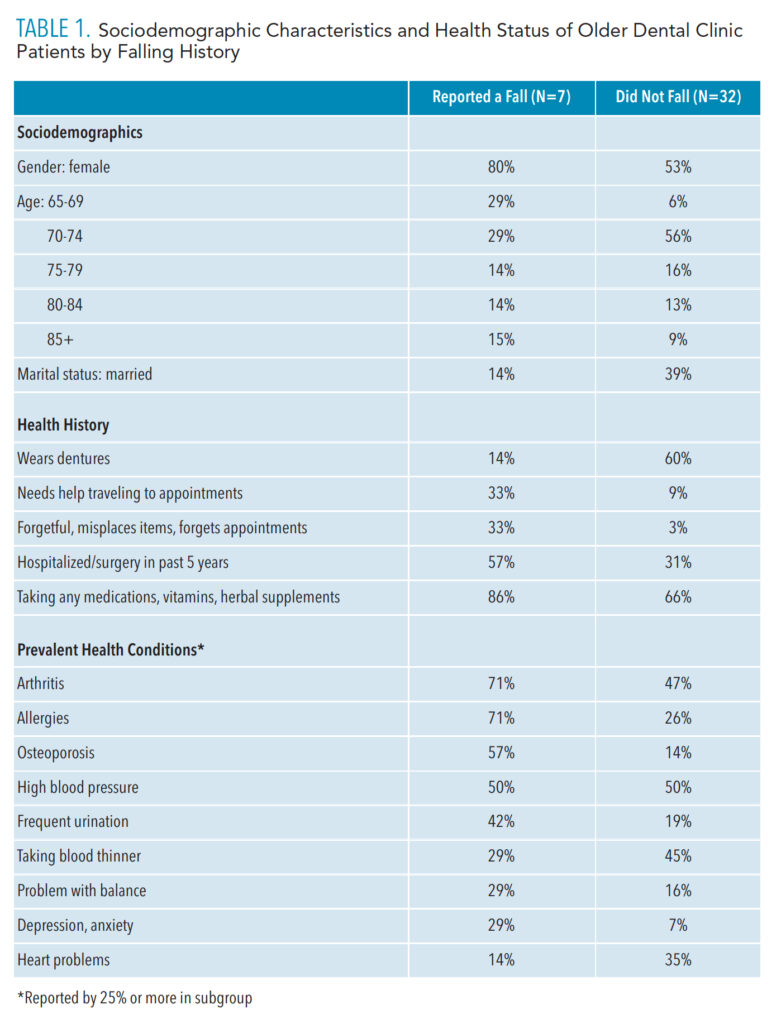

A preliminary investigation was conducted to assess the feasibility and utility of initiating screening and referral for fall risk in community dental clinics. A history of fall and associated risk factors were collected from a convenience sample of patients ages 65 and older attending the New York University College of Dentistry’s low cost dental clinic (N=39). About one in five (18%) reported a fall in the previous year. The older adults who had fallen were more likely to be women, at advanced age (85 and older), and not currently married (Table 1). In terms of functional status, individuals with a history of falls were more likely to report needing to travel to appointments compared to those who did not report a fall (33% vs 9%). Additionally, these older adults were more likely to misplace items and forget appointments than those without a history of failing (33% vs 3%). Regarding physical health status, those who reported falling were more likely than those who did not fall to have been hospitalized or undergone surgery in the past 5 years (57% vs 31%). They also were almost twice as likely as those without a fall to report balance problems (29% vs 16%). And finally, those who had a fall were also more likely than those who did not report a fall to be taking medications, vitamins, or herbal supplements (86% vs 66%). They were also more likely to report having chronic health conditions, such as arthritis (71% vs 47%); allergies (71% vs 26%); and high blood pressure (57% vs 14%).

Overall the insights from this preliminary exploration supports the feasibility of screening for fall risk. Such an initiative would expand the reach of evidence-based, fall-prevention programs to older community residents who could benefit from earlier access to such an intervention. These include older adults who have fallen but have not experienced a serious fall and those who have one or more factors increasing their fall risk (eg, problem with balance) but have not yet fallen. Early implementation of a fall prevention program for these groups of at-risk individuals, could forestall a serious injury.7,8 Not all individuals who experience a fall go on to seek medical follow-up.9

Process of Health Behavior Change

As postulated by the Precaution Adoption Process Model,10 health behavior change is a dynamic process with many determinants, accomplished in a series of cognitive-behavioral stages over time. Informed by this framework, the process of screening patients and making them aware of their health risk acts as a catalyst to move patients from Stage 1 of being “unaware of the issue” to Stage 7 when a decision is made to not only act but to “maintain the action and/or behavior.”10

People move from Stage 1 toward Stage 2 where they are “aware, but unengaged in the issue.” During Stage 3, the contemplation stage, the patient is “undecided about acting,” then progresses to the decision stages, where the patient has either “decided not to act” (Stage 4) or “decided to act, but is not yet in action” (Stage 5). In Stage 5, the decision has been made to “act,” and in Stage 6, “action begins.” Most important, in Stage 7 the decision is forged to “maintain the action.”10 Progressing to this final stage of sustained health behavior change could extend the period of active aging and promote longevity. Providing ongoing screening opportunities for a health condition provides a stimulus that may move an individual toward action or to reconsider an earlier decision not to act.

The Dental Setting as an Outreach Portal for Fall Prevention and Support of Healthy Aging

Limited health research and evidence-based programming have focused on community-based fall prevention, despite the high rate of fall-related morbidity and mortality.7,8 In the US, falls are the leading cause of injury and injury-related death for older adults. Each year, about 30% of community residents ages 65 and older experience a fall, with about one in five falls requiring hospitalization.7 With the aging of the population, the magnitude of this public health issue will continue to grow, as the largest increases in death from a fall are among adults ages 85 and older.9

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that healthcare providers conduct a fall risk evaluation on any community-dwelling adult age 65 and older to assess modifiable risk factors and recommend interventions to reduce these risks.9 Similarly, in a joint statement, the American Geriatrics Society and the British Geriatrics Society recommend that an assessment be done on anyone age 65 and older who presents for medical attention because of a fall, demonstrates difficulty walking or with balance, or reports recurrent falls in the past year.11 The risk of a fall increases with age, with the potential for serious fall-related injury increasing exponentially.7 While the majority of falls occur indoors/at home, outdoor falls are common.12

Fall-prevention efforts that target multiple risk factors have been found to be effective in reducing the frequency and severity of falls.9 However, these programs have typically targeted older adults who have fallen and sustained an injury. Conversely, individuals who have not experienced a serious fall but are at risk of falling would also benefit from referral to assess modifiable risk factors and resources.9 Healthcare providers, such as dental hygienists who are working in dental settings, are ideally situated to take an active role in injury prevention efforts. Similarly, all dental settings are ideal safety nets for the delivery of oral healthcare to older adults. Dental clinics have established linkages and referral patterns across systems of care and specialties that could facilitate referral to preventive services prior to an injury-sustaining event—effectively delaying or preventing a falls-related, unintentional injury.

Summary and Conclusions

Population aging is defining the 21st century. Advances in longevity are fundamentally impacting society, offering both challenges and opportunities. Dental hygienists can play an integral role in public health outreach efforts targeting older adults. Dental hygienists are trained in the art and science of disease prevention and detection. There is a tendency to attribute the symptoms of a disease and functional decline as an inevitable part of the aging process. An interdisciplinary approach and patient-centered care are vital to promoting active aging and reaping the benefits that an extended lifespan provides. Early detection of health risks by dental hygienists and timely access to health promotion resources and services may prevent, delay, or support the effective management of health conditions in older adults.

Integrating tailored health promotion and preventive interventions—such as fall risk assessment and referral—with the delivery of accessible oral healthcare provides a synergistic approach to optimizing function, promoting longevity, and facilitating a pathway to active, healthy aging. Given the incidence of chronic health conditions in aging populations and the comorbidities of oral health conditions with other health issues, the value of providing holistic, patient-centered healthcare delivery is evident. This approach would sustain function, prevent or delay disability, and foster active and healthy aging. Some of the inevitable aspects of aging—such as falling—can be prevented if questions related to falls are included in preliminary dental screenings. Comprehensive dental assessments can result in successful support of healthy aging.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Kim Attanasi, PhD, MS, RDH, for her assistance with this manuscript.

References

- Projected Age Groups and Sex Composition of the Population: Main Projections Series for the United States, 2017-2060. Washington, DC: United States Census Bureau; March 2018.

- Lamster IB, Northridge M. Improving Oral Health for the Elderly: An Interdisciplinary Approach. New York: Springer; 2008.

- Glick M, Greenberg BL. The potential role of dentists in identifying patients’ risk of experiencing coronary heart disease events. J Am Dent Assoc. 2005;136:1541–1546.

- Bin Mubayrik A, Al Dosary S, Alshawaf R, et al. Public attitudes toward chairside screening for medical conditions in dental settings. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2021;15:187–195.

- Greenberg BL, Thomas PA, Glick M, Kantor ML. Physicians’ attitudes toward medical screening in a dental setting. J Public Health Dent. 2015;75:225–233.

- Marshall S, Northridge ME, De La Cruz LD, Vaughan RD, O’Neil-Dunne J, Lamster IB. ElderSmile: A comprehensive approach to improving oral health for seniors. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:595–599.

- Marshall SE, Cheng B, Northridge ME, Kunzel C, Huang C, Lamster IB. Integrating oral and general health screening at senior centers for minority elders. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:1022–1025.

- Panel on Prevention of Falls in Older Persons, American Geriatr Society, British Geriatric Society. Summary of the Updated American Geriatrics Society/British Geriatrics Society clinical practice guideline for prevention of falls in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011,59(148–157.

- Moreland B, Kakara R, Henry A. Trends in nonfatal falls and fall-related injuries among adults aged ≥ 65 years—United States, 2012-2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:875–881.

- Weinstein ND, Sandman P, Blalock SJ. The precaution adoption process model. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K, eds. Health Behavior and Health Education. 4th ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2008:23–47.

- Burns E, Kakara R. Deaths from falls among persons aged ≥ 65 years—United States, 2007-2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:509–514.

- Chippendale T, Raveis V. Knowledge, behavioral practices, and experiences of outdoor fallers: implications for prevention programs. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2017;72:19–24.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. June 2022; 20(6)38-41.