Panoramic Radiographs

How to maximize the benefits of the panoramic image while limiting the risk of radiation exposure.

This course was published in the February 2008 issue and expires February 2011. The author has no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Appreciate the value of panoramic radiographs in evaluating growth and development of the pediatric patient.

- Identify uses of panoramic imaging for the pediatric patient.

- Apply selection criteria guidelines in determining the need for radiographic exposure of children and adolescents.

- Determine the radiographic need of children at different stages of dental development.

- Value ALARA protocol for the pediatric patient.

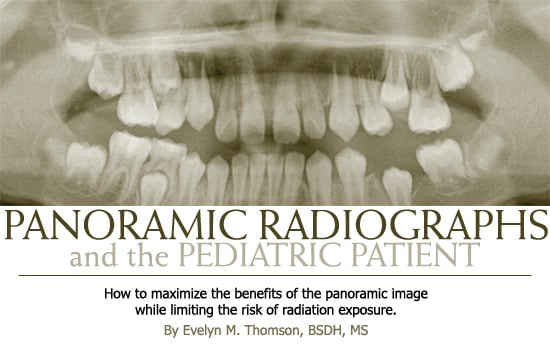

Practicing dental hygienists know the value of the panoramic radiograph in the assessment of the pediatric patient’s oral condition. With its ability to image a broad view of both arches containing the developing and erupting dentition and the supporting periodontal structures all in one image, the panoramic radiograph is invaluable in evaluating growth and development (see Figure 1). Additionally, the ease of obtaining a panoramic image when compared to an intraoral full mouth series can make this technique a reasonable substitute in some cases. However, this ease of use should be a caution to practitioners against overuse. The diagnostic benefits gained from the panoramic radiograph must be weighed against the risk of exposure to ionizing radiation. Through careful use of patient selection criteria and meticulously following as low as reasonably achievable (ALARA) protocol, the dental hygienist will be better prepared to educate anxious parents on the benefits of panoramic radiographs in the treatment and management of the child’s oral health.

Selection Criteria for Radiographs

The panoramic radiograph is useful in dental diagnosis and treatment planning for pediatric patients and can be used to optimize patient care.1-4 In fact, panoramic radiographs have recently received attention, especially for treating children and adolescents. In 2004, the United States Department of Health and Human Services guidelines The Selection of Patients for Dental Radiographic Examinations were accepted as revised by the American Dental Association (ADA) and the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD) along with other dental specialty groups.1,5 The revised guidelines reflect the value and expanded use of panoramic radiographs and recognize that technology has improved significantly in the 15 years since the publication of the original guidelines in 1987.1 The guidelines are not meant as a substitute for professional judgment. Instead, the guidelines present evidence-based practices that can help avoid routine panoramic screening in the absence of suspected pathology.

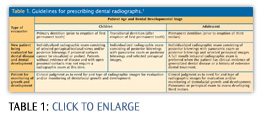

While the value of panoramic radiographs in surveying adult patients for occult diseases continues to be debated, the use of panoramic radiographs to evaluate dental disease and development for the pediatric patient is specifically noted in the revised guidelines (see Table 1).1,6 Because the development and progress of many oral conditions are associated with the patient’s age, stage of chdental development, and vulnerability to known risk factors, the guidelines divide the pediatric patient’s dental age into three stages: primary dentition (generally children under age 6); transitional or mixed primary and permanent dentition (children between the ages of 6 and 12); and permanent dentition (children over age 12). Although assessment of radiographic need should be decided on an individual basis, the suggested use of the panoramic radiograph at each of these stages can assist the practitioner in determining when to recommend the exposure of a panoramic radiograph.

While the value of panoramic radiographs in surveying adult patients for occult diseases continues to be debated, the use of panoramic radiographs to evaluate dental disease and development for the pediatric patient is specifically noted in the revised guidelines (see Table 1).1,6 Because the development and progress of many oral conditions are associated with the patient’s age, stage of chdental development, and vulnerability to known risk factors, the guidelines divide the pediatric patient’s dental age into three stages: primary dentition (generally children under age 6); transitional or mixed primary and permanent dentition (children between the ages of 6 and 12); and permanent dentition (children over age 12). Although assessment of radiographic need should be decided on an individual basis, the suggested use of the panoramic radiograph at each of these stages can assist the practitioner in determining when to recommend the exposure of a panoramic radiograph.

Children Under 6 Years of Age

The guidelines also help practitioners avoid prescribing unnecessary radiographs. Specifically, the guidelines state that prior to the eruption of the first permanent tooth, radiographic examinations—panoramic or intraoral—are not indicated for evaluation of growth and development in the absence of clinical signs or symptoms. Panoramic radiographs are not likely to add beneficial information regarding growth and development for asymptomatic children under age 6. At this stage of dental development, only clinical symptoms of abnormality should prompt the need for radiographs.1

Children Between 6 and 12

Following the eruption of the first permanent tooth, the child enters the transitional dentition stage, and the panoramic radiograph may be a viable option to assess growth and development.1 The increased field of view of the periapical regions revealed by a panoramic radiograph can aid in diagnosing potential eruption problems, especially when exposed early in this stage. For example, the maxillary anterior region may reveal common disturbances such as congenitally missing lateral incisors, ectopic eruption of incisors, or impaction of the canines.7,8 When used in combination with periapical or occlusal radiographs, a panoramic radiograph can assist in determining the bucco-lingual relationship of ectopic or impacted teeth.

9 While intra-oral radiographs provide a sharp, detailed image to evaluate trauma or fractures to teeth and pulp, a diagnostic panoramic radiograph that results from careful exposure techniques is a viable alternative and offers a reduced radiation dose while imaging a larger region.1,10 A panoramic radiograph may also serve as a reliable substitute when patient cooperation in this age group is compromised.

A key point regarding exposure of the panoramic radiograph during the transitional dentition stage is that an initial radiographic exam on a new patient does not usually need to be repeated unless dictated by clinical signs.1 Additional radiographic monitoring during the transitional stage is not required on asymptomatic patients until the eruption of all permanent teeth is complete.

Children Over 12 Years of Age

Panoramic radiographs play an important role in treatment planning for the adolescent patient following the exfoliation of all primary teeth.7,8 In fact, all tooth-bearing regions of the oral cavity should be examined radio-graphically within 2 years following the eruption of the permanent second molars.7 For the adolescent patient, the panoramic radio-graph—when exposed in combination with a set of diagnostic bitewing radiographs—can substitute for a full mouth series. Later in adolescence (patients 16 to 19 years), panoramic radiographs play an important role in evaluating the presence, position, and development of the third molars.1,7 Other examples include the evaluation of the TMJ and the sinuses (see Table 2).

ALARA

The purpose of the selection criteria guidelines is to keep radiation exposure ALARA. Using the guidelines to determine if and when a panoramic radiograph will benefit the pediatric patient assists the practitioner in eliminating unnecessary radiation exposures. Once the need for a panoramic radiograph is assessed, the dental hygienist must determine what steps to take to further keep radiation exposure ALARA. A child’s smaller size and bone density and developing tissues make it imperative that radiation exposure be kept ALARA and that proper radiation protection methods be followed.

The purpose of the selection criteria guidelines is to keep radiation exposure ALARA. Using the guidelines to determine if and when a panoramic radiograph will benefit the pediatric patient assists the practitioner in eliminating unnecessary radiation exposures. Once the need for a panoramic radiograph is assessed, the dental hygienist must determine what steps to take to further keep radiation exposure ALARA. A child’s smaller size and bone density and developing tissues make it imperative that radiation exposure be kept ALARA and that proper radiation protection methods be followed.

Protection begins with assessing the child’s ability to cooperate with the procedure. A child who cannot hold still for the duration of the exposure, usually 15 to 20 seconds, should not undergo the procedure. However, the panoramic technique is often easier to perform than an intraoral full mouth series. The panoramic machine movement can be used as a fun distraction to calm a potentially anxious child and increase the likelihood of producing a diagnostic image.11

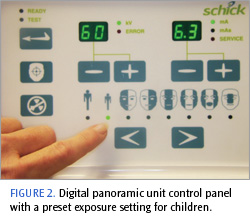

The selection of an exposure setting that produces optimal image density and contrast while minimizing radiation dose is important. Most manufacturers of panoramic machines recommend exposure settings for pediatric patients (Figure 2). Newer intraoral x-ray machines may have default settings that are higher than needed to expose F-speed film and digital sensors.12 The manufacturer’s recommended settings should be assessed to determine if desired results are produced. Carefully examining the diagnostic quality of panoramic radiographs can determine if the recommended settings are appropriate or in need of adjustment.

Panoramic radiographs play an important role in assessment, diagnosis, and treatment planning for the pediatric patient. The use of panoramic radiographs in determining growth and development of the patient in transitional dentition and adolescence is receiving a more prominent focus. Because radiation damage to biological tissues is cumulative over a lifetime, radiation exposure to the pediatric patient must be kept to the minimum required to achieve a diagnostic image.

TABLE 2. USES OF PANORAMIC IMAGING FOR THE PEDIATRIC PATIENTS

- Tooth development

- Eruption pattern disturbance

- Ectopic eruption

- Delayed eruption

- Congenitally missing tooth

- Supernumerary tooth

- Retained tooth or root tips

- Location and development of third molars

- Evaluation of trauma

- Suspected fractures

- Extensive disease

- Large areas of suspected pathology

- Evaluation of TMJ

- Evaluation of sinuses

- Orthodontic survey

- Initial assessment to the need for additional intraoral films

- Localization of buccal or lingual objects when used in combination with intraoral film

- Substitute for periapical films with uncooperative or special needs patients

REFERENCES

- Public Health Service, Food and Drug Administration, American Dental Association Council on Dental Benefit Program, Council on Dental Practice, Council on Scientific Affairs. The Selection of Patients for Dental Radiographic Examinations. Available at: www.ada.org/prof/resources/topics/radiography.asp. Accessed January 16, 2007.

- Monsour P. Getting the most from rotational panoramic radiographs. Aust Dent J. 2000;45:136-142.

- Ketley C, Holt R. Visual and radiographic diagnosis of occlusal caries in first permanent molars and in second primary molars. Br Dent J. 1993;174:364-370.

- Rushton V, Horner K, Worthington H. Routine panoramic radiography of new adults in general practice: relevance of diagnostic yield to treatment and identification of radiographic selection criteria. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 2002;93:488-495.

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Guideline on prescribing dental radiographs for infants, children, adolescents, and persons with special health care needs. Pediatr Dent. 2005;27:185-186.

- American Dental Association. Routine dental panoramic radiograph not necessary. J Am Dent Assoc. 2005;136:584.

- Pinkham PS, Casamassimo P, Fields HW, McTigue DJ, Nowak AJ. Pediatric Dentistry Infancy through Adolescence. 4th ed. St Louis: Elsevier Saunders; 2005:304-306, 506, 677.

- Taylor N, Jones A. Are anterior occlusal radiographs indicated to supplement panoramic radiography during an orthodontic assessment? Br Dent J. 1995;179:377-81.

- White SC, Heslop EW, Hollender LG, Mosier KM, Ruprecht A, Shrout MK. Parameters of radiologic care: an official report of the American Academy of Oral Maxillofacial Radiology. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 2001;91:498-511.

- Sameshima G, Asgarifar K. Assessment of root resorption and root shape: periapical vs. panoramic films. Angle Orthod. 2001;71:185-189.

- McDonald RE, Avery DR, Dean JA. Dentistry for the Child and Adolescent. 8th ed. St Louis: Elsevier Mosby; 2000:71-72.

- Button TM, Moore WC, Goren AD. Causes of excessive bitewing exposure. Results of a survey regarding radiographic equipment in New York. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1999;87:513-517.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. February 2008;6(2): 30-33.