PATRICKHEAGNEY/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

PATRICKHEAGNEY/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

Oral Implications of Gastroesophageal and Laryngopharyngeal Reflux Diseases

Understanding the signs and symptoms of these common health problems can help clinicians educate patients on the best approach to prevent serious oral health issues.

This course was published in the December 2020 issue and expires December 2023. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Define gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR).

- Identify the oral implications of these diseases.

- Discuss how oral health professionals can help patients prevent oral health problems related to GERD and LPR.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) affects up to 50% of adults in the Western world, making it one of the most prevalent diseases in the population.1 GERD is a condition where stomach acid is allowed to flow freely to the esophagus due to the relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) over time. The LES is located at the bottom of the esophagus and relaxes to allow the passage of food and liquid into the stomach. After the nutrients have passed through the esophagus, the LES should close.2 However, in patients with GERD, the LES remains relaxed and allows for stomach acid to flow into the esophagus and potentially into the oral cavity.3 This exchange of acid is called acid reflux.

Risk factors for GERD include routine intake of alcohol, nicotine, and caffeine, and being overweight.4 While these risk factors can be reduced via behavior modification, other factors, such as pregnancy, use of certain medications, and hiatal hernia, cannot always be modified.4 Additionally, GERD does not always follow traditional guidelines and can occur in what most oral health professionals would consider low-risk populations.5 GERD is often found in patients in their 20s and 30s, as well as those who are not overweight.6

Signs and Symptoms

The most common symptom of GERD is heartburn, or inflammation and irritation of the esophagus. Patients with heartburn may seek treatment sooner due to the discomfort, which may reduce the potential for long-term permanent damage.6 Patients may not realize that some symptoms are related to GERD—such as chronic cough, noncardiac chest pain, and even asthma—which may delay treatment.1

Laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) is another form of GERD that is considered atypical because it does not present with the typical GERD symptoms.6 Reflux occurs in patients who have GERD, but the sphincter at the top of the esophagus is also relaxed, allowing for the acid to travel all the way up the esophagus and into the larynx and pharynx.7 While LPR occurs in patients who already have GERD, their symptoms are often different. Those with LPR may not complain of heartburn, and instead may have a hoarse voice, frequent need to clear their throat, trouble swallowing food, and excessive throat mucus.8,9 Patients whose primary diagnosis is GERD will notice their symptoms worsen at night or while lying in a supine position, while symptoms of LPR often occur during the day while sitting or standing upright.5,8 While GERD and LPR exhibit different symptoms, they both can cause harmful oral manifestations that can be pre-cancerous and/or embarrassing.5 Understanding the oral signs and symptoms of both GERD and LPR can help clinicians educate patients on the best treatments to prevent symptoms, but also aid in the prevention of more serious oral conditions.

![Important Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease Assessments]() Oral Manifestations

Oral Manifestations

GERD and LPR have similar oral manifestations, which include tooth erosion, xerostomia, oral malodor, or any combination of these symptoms.4,10

Dental erosion. A comorbidity of chronic GERD, dental erosion is a sign that can be noted during routine dental hygiene treatment.10,11 Dental erosion is when part of the tooth structure, typically the enamel, is lost due to a chemical (nonbacterial) process.11 The eroded portion of the tooth appears yellow and shiny, may have rounded cusps and cupping of occlusal surfaces, and restorations appear to be above the level of other tooth structures.11 In patients with GERD, this chemical process is related to the additional acid entering the oral cavity by the relaxation of the upper and lower esophageal sphincters.2,12

Studies show that dental erosion occurs in approximately 24% of adults diagnosed with GERD,4,13 and up to 98% of children with GERD.14 Anyone with GERD, regardless of the severity, is at risk for dental erosion caused by free-flowing gastrointestinal acid.13 The appearance of teeth eroded by GERD is similar to teeth that have been eroded due to bulimia, with the maxillary anterior lingual surface most frequently affected.15 While it was originally thought that mandibular teeth were protected, multiple studies demonstrate erosion does occur on the mandibular anterior teeth of patients who have stomach acid routinely reaching the oral cavity.13,15 These studies also show that GERD-related erosion and erosion caused by external factors (acidic foods and drinks) can be different. Erosion caused by external factors often presents as a combination of attrition on anterior teeth (with no evidence of bruxism) and buccal cervical noncarious lesions (similar to abfraction in appearance). Variances between the pH in stomach acid (about 1.2) and external acids, depth of the acquired pellicle on various aspects of the teeth, and the body’s ability to produce unstimulated saliva may be the causes of these differences.15

Xerostomia. The salivary flow of patients with GERD is often reduced and, therefore, has a lower buffering capacity when compared to patients without gastrointestinal diseases.13,15 Saliva plays a large role in neutralizing the pH of the oral cavity and cleansing the oral structures to help reduce oral diseases, such as dental caries. Knowing this, it is safe to hypothesize that those patients with free-flowing intestinal acids with low acidic pH (often 1.2 or lower) would benefit from an adequate volume of neutralizing saliva. Unfortunately, the opposite is true and, instead, these patients are almost twice as likely to experience xerostomia, even when considering age and saliva composition.16

Campisi et al16 tested the saliva of patients with and without GERD. Results showed that 57.5% of patients with GERD (test group) experienced xerostomia compared to 28.7% of those without a GERD diagnosis (control group). This study tested both basal and stimulated saliva flow, as well as the pH and electrolyte content. The control group’s saliva averaged a pH of 7.8 while the test group had a statistically higher, more basic pH of 8.9. This higher, more basic pH falls outside of the range of normal saliva pH (5.3 to 7.8) and, theoretically, should have a higher buffering capacity to fight acid attacks. However, this study and another by Jager et al17 demonstrate that electrolyte and potassium composition between test and control saliva is different. The basal salivary flow rate was similar between both the control and test groups; however, the test group had a lower rate of stimulated salivary flow. As the stimulated salivary flow decreased, the pH and potassium levels increased. These changes in saliva content can reduce saliva’s buffering ability and decrease protection of the pellicle. This allows for breakdown of enamel, even though the saliva has a more basic pH. While the exact reason is unclear, it is thought that this change in and/or reduction in saliva could be linked to increased gingival inflammation, burning sensation, and oral malodor.18

Oral malodor. Affecting anywhere between 25% and 65% of the United States population, xerostomia is typically linked to coated tongue, dry mouth, and hard/soft tissue diseases.19,20 However, oral malodor is also linked to systemic disorders, including GERD and LPR.19 In healthy individuals, intestinal acids and their corresponding odors remain in the GI tract. However, in those with GERD and/or LPR, these acids, odors, and sometimes even bacteria can enter the oral cavity and cause malodor.

Considering that some patients are unaware or not diagnosed with GERD and that the nontraditional signs and symptoms of GERD may manifest in the oral cavity before systemic signs occur, oral health professionals can play a role in identifying patients who may have gastrointestinal diseases, and refer patients to primary and/or specialty care physicians.4,21

The Role of the Dental Hygienist

The diagnosis and treatment of reflux conditions, such as GERD and LPR, are imperative to help prevent and manage symptoms as well as prevent future precancerous conditions.4 Due to the potential serious health implications of GERD and LPR, dental hygienists may want to screen for GERD symptoms alongside the oral cancer screening.12

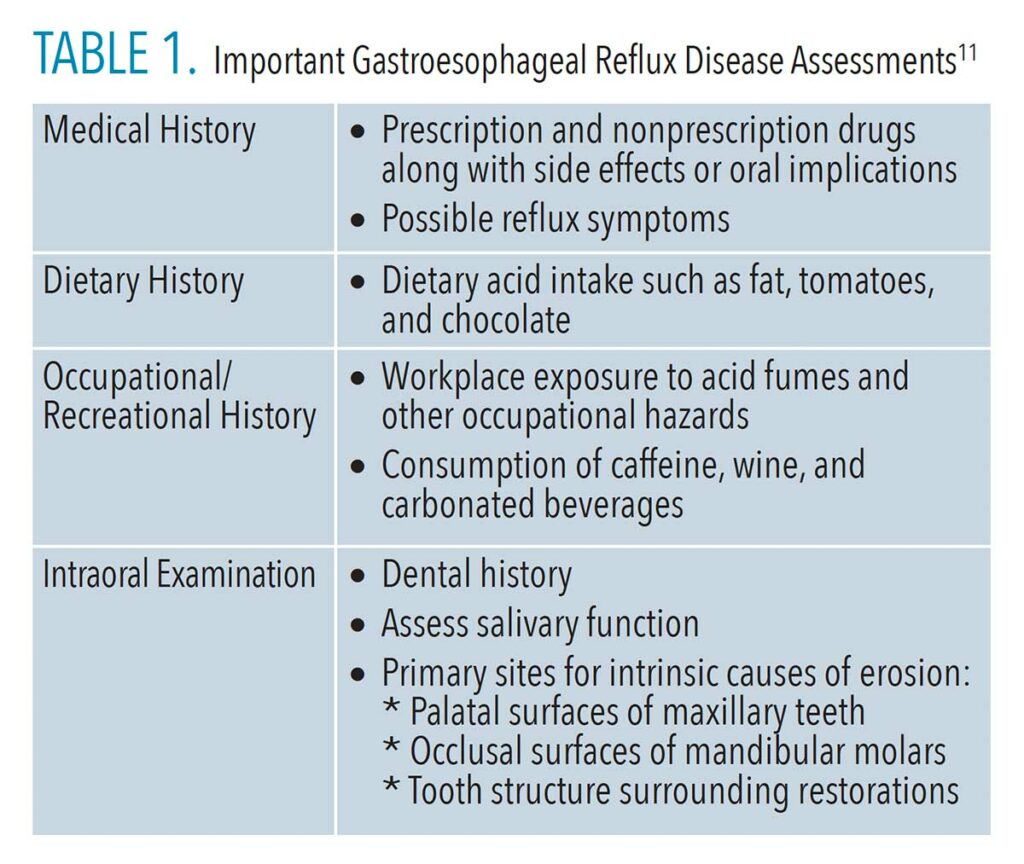

The screening should begin with a full medical and dental history interview with every patient at every appointment. Patients who have nontraditional symptoms may indicate “no” to reflux diseases when completing their medical history form or when verbally asked. Table 1 (page 27) is a helpful guide to use in conversations to help uncover nontraditional GERD symptoms.

After a thorough history has been completed, assessment of the oral cavity for signs of GERD, regardless of whether it is disclosed on a patient’s health history, is vital. The assessment should note the presence of any of the following intraoral signs of GERD:

- Enamel erosion that is not related to history of bulimia on the maxillary anterior lingual surfaces, posterior occlusal surfaces, and mandibular anterior lingual surfaces

- Xerostomia not associated with medication use

- Oral malodor (even mild) when not caused by hard or soft tissues diseases (eg, periodontal diseases or caries)

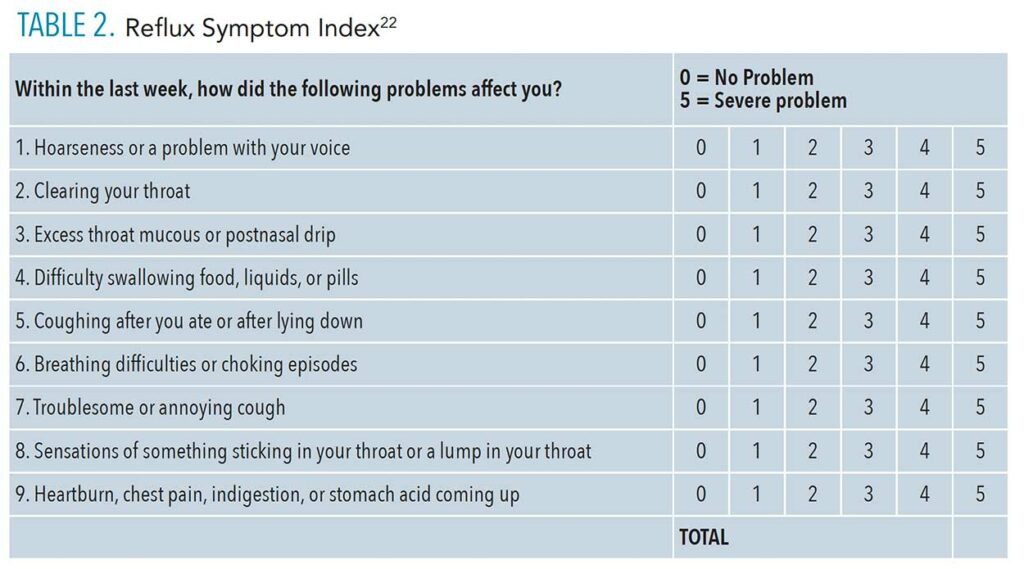

When any of these signs are noted, the clinician should complete detailed documentation in the patient chart and begin a conversation about past history of gastrointestinal diseases. If the patient is unaware of current or previous gastrointestinal diseases, the oral health professional should consider asking about the occurrence of nontraditional symptoms or ask him or her to complete the reflux symptom index (RSI). The RSI is a fast and reliable tool used to help identify patients with GERD or LPR (Table 2, page 28). Scores of 13 or higher are considered abnormal, likely indicate reflux, and could warrant a referral to the patient’s primary care physician for further investigation and diagnosis.9

Once GERD/LPR is identified, it is important to discuss with the supervising dentist and, together, educate the patient on the findings and possible remedies that fall under the dental hygiene scope of practice. Nonpharmaceutical treatments for GERD and LPR can include lifestyle and dietary modifications. Losing weight and reducing or eliminating tobacco and alcohol use can help to improve or eliminate reflux.9 Dietary modifications are also important in the treatment of reflux. Oral health professionals can educate patients on the most common aggravators of reflux symptoms including the consumption of caffeine, carbonated beverages, wine, fat, tomatoes, and chocolate, as well as late-night eating.5,9 It can be difficult to make so many dietary changes at one time. Patients may want to start by decreasing the frequency of harmful foods as well as combining their consumption with main meals. The goal is to successfully decrease the amount of these foods and also limit the amount of time they are in contact with the teeth.11

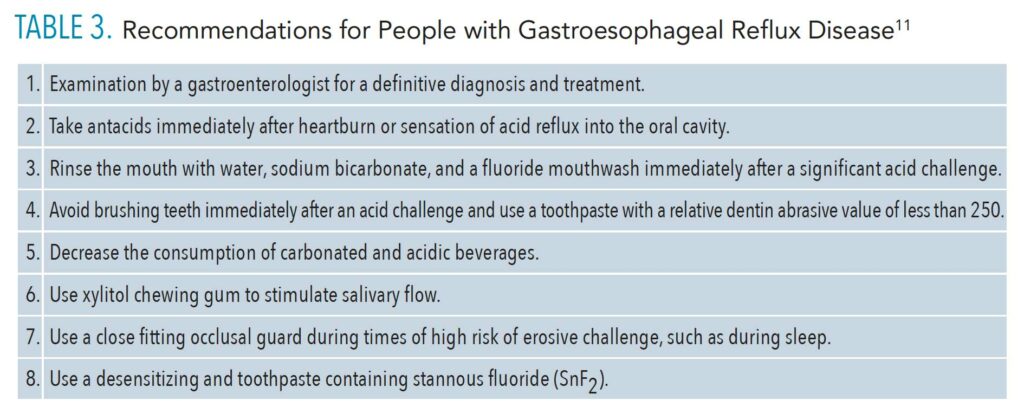

In addition to diet modifications, dental interventions should be considered when enamel erosion has occurred. Although dental erosion is permanent, further destruction can be prevented, and current tooth structure can be strengthened through over-the-counter and/or prescription topical fluoride applications. A toothpaste containing stannous fluoride (SnF2) may be recommended, as it seems to provide greater protection against erosive challenges than dentifrices containing sodium fluoride only or a combination of sodium fluoride and potassium nitrate.23 While sucking or chewing sugar-free mints and mint-flavored gum is a common recommendation to increase saliva flow and mask oral malodor, patients with GERD should avoid these as mint can increase symptom severity.5

For patients with a current or previous history of GERD, oral health professionals can provide a written at-home chart for what to do when they experience a reflux incident. Table 3 provides an example.

Conclusion

Reflux disorders, such as GERD and LPR, do not always present with the most common signs and symptoms, leaving them potentially difficult to diagnose and treat. Oral health professionals can play an important role in aiding in the detection of these potential cancer-causing diseases and making the appropriate referrals. Clinicians should not only be aware of possible oral manifestations of reflux disorders, but also assess and communicate their findings with the patient. Awareness of reflux, as well as its related oral manifestations, enables oral health professionals to help patients prevent future oral conditions and seek the treatment they need.

References

- Wood JM, Hussey DJ, Woods CM, Watson DI, Carney AS. Biomarkers and laryngopharyngeal reflux. J Laryngol Otol. 2011;125:1218-1224.

- Gifford-Jones W. GERD and LES culprits in angina-mimicking pain. The Windsor Star. March 1995:B4.

- Mayo Clinic. Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Available at: mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/gerd/symptoms-causes/svc-20361940. Accessed November 20, 2020.

- Ranjitkar S, Kaidonis JA, Smales RJ. Gastroesophageal reflux disease and tooth erosion. Int J Dent. 2012;2012:479850.

- Koufman JA. Low-acid diet of recalcitrant laryngopharyngeal reflux: therapeutic benefits and their implications. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2011;120:281–287.

- Koufman J, Stern J, Bauer M. Dropping Acid The Reflux Diet Cookbook and Cure. 6th ed. Elmwood Park, New Jersey: G&H Soho Inc; 2015.

- Martinucci I, de Bortoli N, Savarino E, et al. Optimal treatment of laryngopharyngeal reflux disease. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2013;4:287–301.

- Koufman JA, Belafasky PC, Bach KK, Daniel E, Postma GN. Prevalence of esophagitis in patients with pH-documented laryngopharyngeal reflux. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:1606–1609.

- Campagnolo AM, Priston J, Thoen RH, Medeiros T, Assuncao AR. Laryngopharyngeal reflux: Diagnosis, treatment, and latest research. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2014;18:184–191.

- Warsi I, Ahmed J, Younus A, et al. Risk factors associated with oral manifestations and oral health impact of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a multicenter, cross-sectional study in Pakistan. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e021458.

- Dunbar A, Sengun A. Dental approach to erosive tooth wear in gastroesophageal reflux disease. Afr Health Sci. 2014;14:481–486.

- Raibrown A, Giblin LJ, Boyd LD, Perry K. Gastroesophageal reflux disease symptom screening in a dental setting. J Dent Hyg. 2017;91:44–48.

- Yoshikawa H, Furuta K, Ueno M, et al. Oral symptoms including dental erosion in gastroesophageal reflux disease are associated with decreased salivary flow volume and swallowing function. J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:412–420.

- Canadian Society of Intestinal Research. GERD and Dental Erosion. Available at: badgut.org/information-centre/a-z-digestive-topics/gerd-dental-erosion/. Accessed November 20, 2020.

- Valena V, Young WG, Dental erosion patterns from intrinsic acid regurgitation and vomiting. Aust Dent J. 2002;2:106–115.

- Campisi G, Lo Russo L, Di Liberto C, et al. Saliva variations in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. J Dent. 2008;36:268–271.

- Jager DHJ, Vieira AM, Ligtenberg AJM, Bronkhorst E, Huysmans MCDNJM, Vissink A. Effect of salivary factors on the susceptibility of hydroxyapatite to early erosion. Caries Res. 2011;45:532–537.

- Watanabe M, Nakatani E, Yoshikawa H, et al. Oral soft tissue disorders are associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease: retrospective study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2017;17:92.

- Campisi G, Musciotto A, Di Fede O, Di Marco V, Craxì A. Halitosis: Could it be more than mere bad breath? Intern Emerg Med. 2011;6:315–319.

- Karin K, Wilder-Smith CH, Bornstein MM, Lussi A, Seemann R. Halitosis and tongue coating in patients with erosive gastroesophageal reflux disease versus nonerosive gastroesophageal reflux disease. Clin Oral Invest. 2013;17:159–165.

- Ignat A, Burlea M, Lupu VV, Paduraru G. Oral manifestations of gastroesophageal reflux disease in children. Romanian Journal of Oral Rehabilitation. 2017;9(3):40–43.

- Belafsky PC, Postma GN, Koufman, JA. Validity and reliability of the reflux symptom index (RSI). J Voice. 2002;16:274–277.

- Hooper S, Seong J, Macdonald E, et al. A randomized in situ clinical trial, measuring the ant-erosive properties of a stannous-containing sodium fluoride dentifrice compared with a sodium/potassium nitrate dentifrice. Internat Dent J. 2014;64(Suppl 1):35–42.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. December 2020;18(11):26-28,31.