BY ED UTHMAN FROM HOUSTON, TX, USA - LYMPHOCYTIC GASTRITIS, CC BY 2.0,

HTTPS://COMMONS.WIKIMEDIA.ORG/W/INDEX.PHP?CURID=82958634

BY ED UTHMAN FROM HOUSTON, TX, USA - LYMPHOCYTIC GASTRITIS, CC BY 2.0,

HTTPS://COMMONS.WIKIMEDIA.ORG/W/INDEX.PHP?CURID=82958634

The Oral Impact of Celiac Disease

Patients with this genetic, autoimmune disorder experience significant oral health effects.

This course was published in the January 2020 issue and expires January 2023. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Define celiac disease (CD), its prevalence, and clinical signs.

- Describe the effect of CD on nutrient absorption.

- Identify the oral conditions that may serve as risk factors for CD.

Celiac disease (CD) is a hereditary, autoimmune disease induced by a reaction to gluten. Gluten is found in wheat (breads, soups, pastas, cereals, sauces, and salad dressings); rye (rye breads and beer); and barley (malt products, food colorings, soups, beer, and brewer’s yeast).1,2 Nonfood products that may contain gluten, such as Play-Doh, cosmetics, skin and hair products, toothpaste, and mouthrinse, may transfer gluten from hands to the mouth.1,2

CD affects approximately one in 100 people internationally.3 The United States, Argentina, Italy, Germany, Denmark, and Finland have a higher prevalence of CD compared with other countries. Found more often in white females, CD is also hereditary. Those with a parent, child, or sibling with CD are at a one in 10 risk of also receiving a CD diagnosis.4 Environmental factors—such as the introduction of gluten at an early age, absence of breastfeeding, and viral infections during infancy—may increase the risk of CD.5,6

In the United States, 2.5 million individuals remain undiagnosed, which can lead to significant health problems, ranging from iron-deficiency anemia to infertility and miscarriage to neurological problems.4 CD may appear at any age, and a diagnosis raises the risk for other autoimmune diseases that are genetically and immunologically linked to CD (Table 1).7–9

The clinical signs of CD differ between children and adults. Among children, CD may cause weight loss; delayed tooth eruption; stained, pocked, and grooved enamel defects; and recurring aphthous ulcers. Signs of CD in adults may include abdominal discomfort, chronic diarrhea, bloating, weight loss, joint pain, muscle cramping, seizures, skin rashes, infertility and miscarriage, peripheral neuropathy, osteoporosis, atrophic glossitis, xerostomia, and aphthous ulcers.10,11

![]() NUTRIENT ABSORPTION

NUTRIENT ABSORPTION

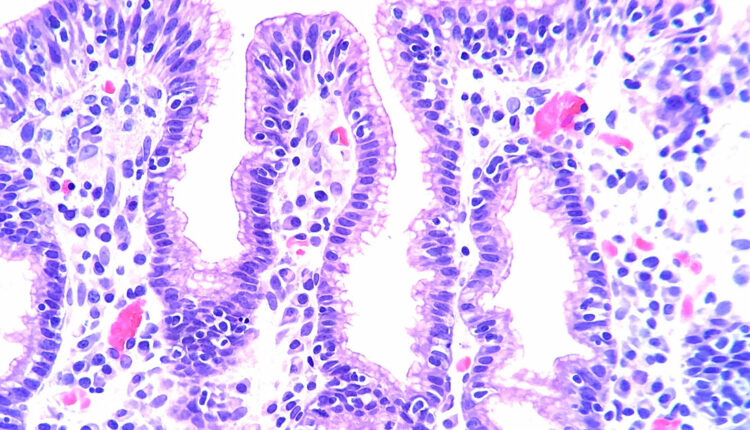

CD damages the villi of the small intestines, which impedes the body’s ability to absorb nutrients (Figure 1). When individuals with CD are exposed to alpha gliadin, a protein found in gluten, the body creates a T-cell mediated inflammatory response in which IgA antitussive transglutaminase, antiendomysial, and antigliadin antibodies are released. This reaction damages the brush border in the small intestine, which consists of folds of Kerckring that contain villi and microvilli, which are used for nutrient absorption. Through the inflammatory response, the villi are flattened.

The decreased absorption of nutrients caused by CD includes those that play a key role in tooth development, such as the minerals calcium and fluoride.

DIAGNOSIS

Early detection and diagnosis of CD can be difficult because patients are frequently unaware of their risk for the disease. Finances may prohibit diagnosis when there is a lack of health insurance coverage or financial ability to consult a primary physician. In addition, CD mimics irritable bowel syndrome and lactose intolerance, further increasing the difficulty of diagnosis.

The following are part of a CD diagnosis:

- Presence of clinical signs, including rash, fullness in the abdomen, deformity of tooth enamel, and history of aphthous ulcers.

- Genetic blood tests (more than 40 genes are associated with CD; HLA-DQ2 and HLA-DQ8 are present in 85% of patients).

- Intestinal biopsy of the small intestine.

- Skin biopsy to check for antibodies if dermatitis herpetiformis is present.

ORAL SIGNS AND EFFECTS

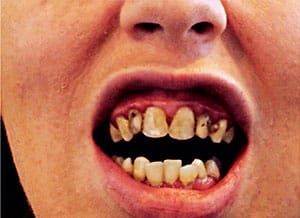

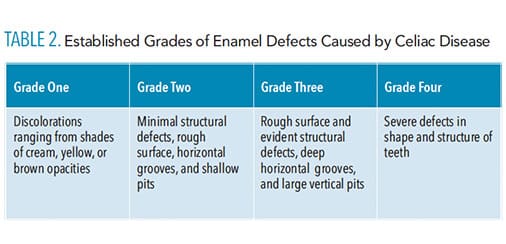

Oral health professionals should be aware of the signs of CD, including enamel deformity reported by established enamel grades of CD (Table 2) and history of recurring aphthous ulcers and dermatitis herpetiformis.12,13

Children with CD are at increased risk for dental caries.4 Delayed tooth eruption, mandibular jaw defects, enamel impairments, altered matrix formation, hypocalcification, and burning sensations in the oral cavity are other oral signs of CD. Patients who develop CD before age 7 are at greatest risk of negative effects in their permanent dentition. Dental defects can be used as a warning sign of CD in children and infants.14,15 Children with CD may develop patchy white-yellow colorations on their teeth, or enamel hypoplasia, which may cause the dentition to appear ridged and pitted. In some cases, the teeth may present with a distinct groove, a sign of a significant enamel impairment.16,17

Patients with CD are at increased risk for xerostomia, which increases the risk of caries; aphthous ulcers; aphthous stomatitis; atrophic glossitis; and, in some cases, oral cancer, especially squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx.4,7,18–21

![]() ROLE OF THE DENTAL HYGIENIST

ROLE OF THE DENTAL HYGIENIST

When treating patients with CD, interprofessional collaboration and solid communication between the dentist, dental hygienist, and other medical team members are imperative. The first step is to consult with the patient’s medical team members prior to beginning any dental treatment. They will have a wide-range view of the patient’s current health status and can provide guidance on the appropriateness of dental care.

In the dental practice, dental hygienists are often the first point of contact with patients. As such, they must be aware of any dental products that contain gluten, such as prophy paste, toothpaste, and floss, so clinicians must ensure that alternative products for patients with CD are available. The practices’ dental dealer representative should be able to suggest gluten-free products.

Taking diagnostic radiographs, performing a thorough clinical assessment, and gathering a concise medical, dental, and familial history are the foundations of a decisive and complete treatment plan.

Dental hygienists must be aware of the possible oral manifestations that can arise in patients with CD. Some adjustments in patient care may be needed to ensure patient comfort. Clinicians can recommend products to soothe aphthous ulcers and an extra soft toothbrush should be suggested, especially if there is irritation in the mouth. In addition, if the patient has xerostomia, moisturizing oral health products are recommended, as well as home fluoride treatment with possible tray fabrication/application. Fluoride varnish is helpful to reduce caries risk due to its viscosity and effective uptake within the tooth structures.

Patients with CD will need preventive services on 3-month to 4-month intervals so the oral status can be reviewed and evaluated. A thorough dietary analysis may assist with educating patients on how to improve their nutritional intake, especially of calcium and fluoride, which are imperative to oral health. This would be in collaboration with the primary care physician and/or dietitian.

CASE STUDIES

Case Study 1. A 27-year-old woman presented to the dental office with concerns regarding the esthetics of her smile. She had red, ulcerated tissue and bleeding, with plaque and calculus irritating the marginal gingiva (Figure 2). The resultant pain interfered with her ability to brush regularly. Her medical history noted a diagnosis of CD; allergies to phenazopyridine hydrochloride, hydromorphone hydrochloride, penicillin, and azithromycin; hypertension; chronic bronchitis and cough; sinus problems; allergy/hives; bruises easily; ulcers; syncope; and vertigo. She had a history of anemia and arthritis and was on a daily calcium supplement. Her medication regimen included hydrocodone 500 mg, three times daily; liquid lidocaine 2% viscous solution, 1 teaspoon every 6 hours to 8 hours; amoxicillin 500 mg, once daily for 6 weeks; and alprazolam 5 mg daily.

Tooth #16 was partially erupted with severe caries and the crown was decayed to the gumline with possible chronic periapical abscess present. The patient had severe caries throughout her dentition. Porcelain-fused-to-metal (PFM) crowns were needed on #6 to 11 due to severe caries. Tooth #15 and 16 MOD required extraction due to severe caries.

On the initial dental appointment, the dentist suggested the patient use prescription-strength fluoride gel in fabricated bleaching trays to wear once daily. The dentist recommended that the patient see a specialist but she declined due to a lack of dental insurance and financial constraints.

The initial treatment plan was to place PFM crowns on #6 to 11. The dentist completed resin restorations on #7, 10, 11 facials due to severe caries and enamel breakdown on these surfaces, which was a temporary solution.

At another appointment, the dentist placed a resin-one surface posterior restoration on #14 lingual. The next week, the patient reported losing the filling on #14 and severe pain described as “fire ants continually biting.” The dentist suggested the need for extraction by an oral surgeon. She was given a prescription for hydrocodone bitartrate/acetaminophen and zithromax/azithromycin for 5 days.

The following week, the patient reported no improvement and still had burning near the teeth that had recently been filled. The patient was given another prescription for hydrocodone bitartrate/acetaminophen and viscous lidocaine 100 ml for pain. The patient was unable to return to the dental practice for treatment and did not continue with the treatment plan.

Case Study 2. An 18-year-old woman with CD but no other health history concerns presented to the dental office with generalized moderate to severe decalcification on many teeth and recurrent caries (Figure 3). The dentist suggested wearing trays filled with casein phosphopeptide–amorphous calcium phosphate paste overnight. A review of acidity intake was performed and the patient’s consumption of diet soft drinks was discussed with the recommendation made to limit or eliminate such consumption. Fluoride varnish was applied at each preventive maintenance appointment. On two separate occasions, the patient was prescribed 21 pills of 500 mg amoxicillin with no refills for infection.

DISCUSSION

As is demonstrated in these case studies, CD can have a disasterous effect on patients’ oral health, especially those who have limited access to professional dental care. Patients with CD are very difficult to restore due to the fragility of their dentition. Each time a dentist prepares the teeth for composite restorations, the more tooth structure is sacrificed and the strength of the restoration is diminished. In addition, some patients with CD have a tendency for diminished healing, hence, there is significant concern when extracting teeth.

Patients with CD may have no other choice than to have their teeth extracted. Decreased healing can affect the oral tissues and bone support; in addition, patients may struggle with wearing dentures because of the potential of ulcerative gingiva and increased inflammation on the ridges of bone. Patients with CD will need to be educated on all aspects of treatment and informed of the treatment goals and strategies that are specifically designed for their needs. Obtaining informed consent is of the utmost importance.

CONCLUSION

The prevalence of CD is growing, especially in the US.22 Patients may seek dental care without knowing of their condition. Oral health professionals are well-positioned to note this disease’s oral signs and symptoms. A thorough medical, familial, and dental history will aid in proper diagnosis and treatment. Oral health professionals who suspect CD should speak with not only the patient but also his or her physician and/or dietitian to determine an effective treatment strategy. This interdisciplinary approach will support the successful management of CD, as well as mitigate its effects on oral health.

REFERENCES

- Celiac Disease Foundation. The big 3: wheat, barley, rye. Available at: celiac.org/gluten-free-living/what-is-gluten/. Accessed December 4, 2019.

- Kelly CP, Bai JC, Liu E, Leffler DA. Advances in diagnosis and management of celiac disease. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:175–186.

- Singh P, Arora A, Strand TA, et al. Global prevalence of celiac disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:823–836.

- Celiac Disease Foundation. Oral Health. Available at: https://celiac.org/about-celiac-disease/related-conditions/oral-health/. Accessed December 4, 2019.

- Nelms M, Sucher K, Lacey K, Roth SL. Nutrition Therapy and Pathophysiology. 3rd ed. Boston: Cengage Learning; 2019:405–406.

- Parzanese I, QehajaJ D, Patrinicola F, Aralica M, Chiriva-Internate M, Stifter S. Celiac disease: from pathophysiology to treatment. World J Gatrointest Pathophysiol. 2017;8:27–38.

- Celiac Disease Foundation. What Is Celiac disease? Available at: celiac.org/about-celiac-disease/what-is-celiac-disease/. Accessed December 4, 2019.

- Laurett E, Rodrigo L. Celiac disease and autoimmune-associated conditions. Biomed Res Int. 2013:127589.

- Gluten Intolerance Group. Associated Autoimmune Diseases. Available at: gluten.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/EDU_AssociatedAuto_5.12.14.pdf. Accessed December 4, 2019.

- Byrd-Bredbenner C, Moe G, Beshgetoor D, Berning J. Wardlaw’s Perspectives in Nutrition. 9th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Co Inc; 2013:142–661.

- Vivas S, Vaquero L, Rodriguez-Martin L, Caminero A. Age-related differences in celiac disease: specific characteristics of adult presentation. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther. 2015;6:207–212.

- Rashid M, Zarkadas M, Anca A, Limeback H. Oral manifestations of celiac disease: a clinical guide for dentists. J Can Dent Assoc. 2011;77:39.

- Amato M, Zingone F, Caggiano M, Iovino P, Bucci C, Ciacci C. Tooth wear is frequent in adult patients with celiac disease. Nutrients. 2017;9:1321.

- Zylberberg HM, Lebwohl B, RoyChoudhury A, Walker M, Green PHR. Predictors of improvement in bone mineral density after celiac disease diagnosis. Endocrine. 2018;59:311–318.

- Al-Homaidhi M. The effect of celiac disease on the oral cavity. Available at: medcrave.com/articles/det/12437/The-Effect-of-Celiac-Disease-on-the-Oral-Cavity-A-Review. Accessed December 9, 2019.

- Sheetal A, Hiremath VK, Patil AG, Sajjansetty S, Kumar SR. Malnutrition and its outcome-a review. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7:178–180.

- Anderson J. Effects of celiac disease on your teeth and gums. Available at: verywellhealth.com/effects-of-celiac-disease-on-dental-health-4115330. Accessed December 4, 2019.

- Drummond BK, Kilpatrick N. Planning and Care For Children and Adolescents With Dental Enamel Defects Etiology, Research and Contemporary Management. Berlin: Springer; 2015:1–14.

- Dombrowski M. Celiac teeth: celiac disease and oral health. Available at: colgate.com/en-us/oral-health/conditions/gastrointestinal-disorders/celiac-teeth-celiac-disease-oral-health-0715. Accessed December 4, 2019.

- Saccucci M, DiCarlo G, Bossu M, Giovarruscio F, Salucci A, Polimeni A. Autoimmune diseases and their manifestations on oral cavity: Diagnosis and clinical management. J Immunol Res. 2018;2018:6061825. Accessed December 4, 2019.

- Lewis MAO, Wilson NHF. Oral ulceration: causes and management. The Pharmaceutical Journal. 2019;302(7923):e10.

- Offord C. The celiac surge. Available at: the-scientist.com/features/the-celiac-surge-31438. Accessed December 4, 2019.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. January 2020;18(1):26–29.

NUTRIENT ABSORPTION

NUTRIENT ABSORPTION ROLE OF THE DENTAL HYGIENIST

ROLE OF THE DENTAL HYGIENIST