Innovations in Scope of Practice

The career paths for dental hygienists continue to expand, providing additional professional opportunities and improving access to care.

For more information about scope of practice and dental therapy, read Dimensions of Dental Hygiene’s annual supplement Perspectives on the Midlevel Practitioner at: dimensionsofdentalhygiene.com/perspectives-on-the-midlevel-practitioner.

Over the past decade, legislatures across the United States have grappled with scope of practice issues for health professions, including dental hygiene. Almost every state has provided new permissions or enabled conditions for broader practice in response to new technology, improved science, novel dental materials, or alternative methods for delivery of care. Downstream effects of these changes include opportunities for innovative dental hygiene practice. In addition, the fundamental shift in health care delivery away from the medical paradigm of identifying and treating existing disease toward early intervention in prevention of disease processes has had collateral effects on dentistry and dental hygiene. Dental hygienists’ competencies are grounded in patient education, motivational interviewing, and preventive and prophylactic clinical services. This expertise has positioned the profession to play a pivotal role in efforts to improve the oral health of the US population. Dental hygienists are now more commonly viewed as primary preventive oral health specialists with separate and critical responsibilities in the oral health care continuum of care.

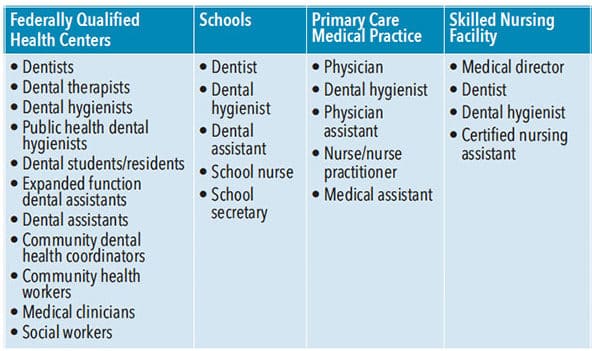

Dental hygiene has evolved from a somewhat limited role in private dental practices to multiple functions in a variety of dental, medical, educational, and social service provider organizations. While many dental hygienists continue to offer important services in private practice settings, an increasing number are embracing opportunities for expanded practice. These broader opportunities offer different ways in which dental hygienists can serve patients and provide new portals of entry for patients to the oral health care delivery system. One critical function for dental hygienists is to act as a first point of patient contact with oral health services, providing referral to and consultation with other members of clinical dental teams. The emergence of team-based service delivery in oral health care represents an environmental shift that encourages more flexible use of the competencies of various health professions to enable high-quality, high-value, and efficient patient-centered services. Dental hygienists working in skilled nursing facilities consult closely with medical and nursing staff and in school-based programs, they work with administrative staff, nurses, and teachers. Teledentistry teams often include dental hygienists, as well as information technology staff who are critical to delivering remote consultation services. The skills needed by dental hygienists to work effectively with different professional disciplines are similar to those needed to provide compassionate patient care, including communication and interpersonal skills, flexibility, conflict management, cultural awareness, empathy, ethics, and critical-thinking and problem-solving skills.1,2 Table 1 lists examples of various health care teams where dental hygienists might practice.

OVERCOMING BARRIERS TO CARE

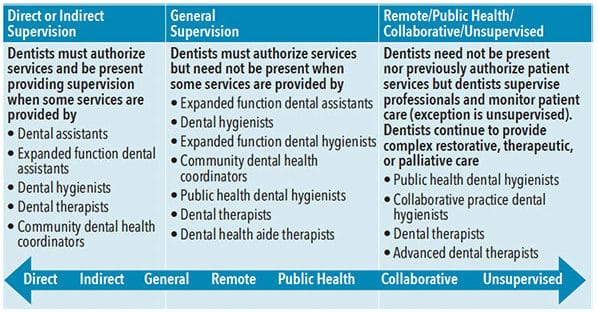

A fundamental change to the effective use of dental hygienists is the ability to provide clinical services with less direct oversight in settings other than traditional dental practices. Legislators and regulators recognize that the traditional delivery system is not designed to meet the needs of underserved populations and that barriers to obtaining oral health services are overcome when services are delivered in community settings where patients are commonly found.

Changes in legal scope of practice have expanded the settings in which dental hygiene services can be provided to schools, government programs for families and infants (eg, WIC), residences for older adults/those with special needs, correctional facilities/juvenile detention centers, governmental agencies, mental health facilities, assisted living residences, skilled nursing facilities, and even the homes of patients.

These changes appear to be impacting care delivery. According to the School-Based Health Alliance National School Based Health Care Census, an analysis of 20 years of census data found that the proportion of school-based health centers (2,584 in 2016-2017 academic year) that employed oral health professionals in the health clinic increased from 9% in 2001-2002 to 28% in 2016-2017.3,4 School districts throughout the US without fixed clinics are collaborating with mobile dentistry providers to meet the needs of children with limited access to oral health services. For example, a dental hygienist-owned nonprofit organization, Future Smiles, provides services in approximately 50 schools in Nevada using a mixed model of care delivery. In some schools, care is provided in dental chairs within the school during the academic year; in others, dental hygienists use portable equipment.5 Two of the school campuses have separate buildings for fixed operatories where dental hygiene services are provided on a year-round basis. Approximately 5,000 children receive clinical services annually and another 20,000 children receive oral health education.

In South Carolina, there are 61 school-based health centers; 30 of these provide only telehealth services, thus, oral health services are not commonly available.4 A for-profit dental hygiene organization, Health Promotion Specialists, provides dental hygiene services to approximately 23,000 children annually throughout the state using portable equipment and delivering services in neighborhood schools. Most of the children served are Medicaid eligible. The dental hygienists work with the state sealant program to fulfill reporting requirements to meet Healthy 2020 goals for their communities.

In 2016-2017, one of every five schools with health centers were using some form of telehealth to provides services to students or to school communities.4 One example is a portable dental hygiene program in three elementary schools in Polk County, Oregon, in which a dental hygienist provides prophylactic services to students and uses teledentistry technology to capture, store, and forward diagnostic images and assessments to a collaborating dentist for treatment planning for enrolled students.6

Public health dental hygiene practice is available in almost every state, although the pathways to the designation, allowable services, and required levels of supervision vary by jurisdiction. Public health dental hygiene is defined differently across states; it may take the form of collaborative practice, a limited access permit, an extended care permit, or expanded practice dental hygiene. For example, dental hygienists may qualify for independent practice in Colorado and Maine, unsupervised practice with an expanded practice permit in Oregon, stepwise extended care permits in Kansas, public health dental hygiene in Massachusetts and Nebraska, collaborative practice in New Mexico, and alternative practice in California.7 These agreements enable qualified dental hygienists to offer direct access to patients who have not had a recent dental visit and to provide a full range of educational, preventive, and prophylactic dental hygiene services in the community (Table 2).

NEW ORAL HEALTH WORKFORCE MODELS

Several states have enabled new oral health workforce models, generically labeled as dental therapy, which allow professionals who have trained in an accredited curriculum and program and passed clinical and written examinations to provide basic restorative services, primary tooth extractions, and preventive oral health services to underserved patients. In Minnesota, an advanced dental therapist may also carry a dental hygiene license and provide a broad range of preventive and restorative services including pulpotomies on primary teeth and tooth extractions under the general supervision of a dentist. Maine, Vermont, Arizona, New Mexico, Nevada, and Connecticut have also passed legislation enabling dental therapy licenses to dental hygienists who will be required to pursue further education and training for licensure.

These opportunities represent an emerging career ladder for dental hygienists. While these opportunities may still represent exceptional practice for the profession, it is expected that dental hygienists will more commonly pursue some of these roles in the future as provider organizations engage with new models for care delivery.

Like Dimensions’ Facebook page at: facebook.com/dimensionsofdentalhygiene/ and leave a comment on this question: “Do you see expanding opportunities for dental hygienists in your area?” One respondent will receive a coupon for a free continuing education course!

REFERENCES

- Sisodia S, Agarwal N. Employability skills for healthcare industry. Procedia Computer Science. 2017;122:431–438.

- Dalaya M, Ishaquddin S, Ghadage M, Hatte G. An interesting review on soft skills and dental practice. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9:ZE19–ZE21.

- School-Based Health Alliance. National School-Based Health Care Census. Available at: sbh4all.org/school-health-care/national-census-of-school-based-health-centers/. Accessed December 5, 2019.

- Love HE, Schlitt J, Soleimanpour S, Panchal N, Behr C. Twenty years of school-based health care growth and expansion. Health Affairs. 2019;38:5.

- Langelier M, Moore J, Carter R, Boyd L, Rodat C. An assessment of mobile and portable dentistry programs to improve population oral health. Available at: oralhealthworkforce.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/OHWRC_Mobile_and_Portable_Dentistry_Programs_2017.pdf. Accessed December 5, 2019.

- Langelier M, Rodat C, Moore J. Case studies of 6 teledentistry programs: strategies to increase access to general and specialty dental services. Available at: oralhealthworkforce.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/OHWRC_Case_Studies_of_6_Teledentistry_Programs_2016.pdf. Accessed December 5, 2019.

- Langelier M, Baker B, Continelli T. Development of a new dental hygiene professional practice index by state, 2016. Available at: oralhealthworkforce.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/OHWRC_Dental_Hygiene_Scope_of_Practice_2016.pdf. Accessed December 5, 2019.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. January 2020;18(1):16–17.