LUMINEUX_IMAGES/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

LUMINEUX_IMAGES/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

Oral Health Strategies for Patients Who Use Medical Cannabis

With cannabis use increasing across the United States, oral health professionals need to be prepared to address the dental needs of this population.

This course was published in the April 2021 issue and expires April 2024. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Define cannabis and its uses.

- Describe the oral health implications of cannabis use.

- Identify management strategies for patients who use medical cannabis.

Cannabis is the most commonly used psychoactive drug in the United States and around the world.1,2 While most cannabis use is recreational, more than 4 million Americans use cannabis for medicinal purposes.3–5 The availability of cannabis and diversity of cannabis-derived products are rapidly changing in the US.6 Oral health professionals are likely to encounter patients who are either prescribed cannabis-derived drugs or have a license to purchase medical marijuana from a dispensary.

“Cannabis,” “marijuana,” and “hemp” are terms that should not be used interchangeably. Cannabis sativa, Cannabis indica, and Cannabis ruderalis are varieties of plants from the Cannabaceae family that contain active chemical compounds that include delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD). Strains of C. sativa have high levels of THC and little or no CBD, while strains of C. indica have moderate levels of THC and CBD. Strains of the C. ruderalis group contain low to moderate levels of THC and high levels of CBD. The federal government defines cannabis as all parts of the C. sativa plant.7 Marijuana only includes the parts of the C. sativa plant with significant amounts of THC.8 Hemp refers to industrial uses of cannabis, and it is commonly used as fiber for textiles.7,9

Cannabinoids are a group of active cannabis compounds undergoing study for many potential therapeutic uses. More than 100 cannabinoids have been identified in the cannabis plant, but THC and CBD have garnered the most interest. THC is a potent substance primarily responsible for causing psychoactive effects that create the sense of euphoria often associated with marijuana use.2,5,8 CBD is a nonintoxicating substance that may offer potential therapeutic use for inflammation, pain, anxiety, and a variety of other ailments. The discovery of the endocannabinoid system (ECS) in the early 1990s has improved the understanding of the role cannabinoids play in maintaining homeostasis.10 Composed of a network of receptors, signaling molecules, and enzymes, the ECS is involved with inflammation, pain modulation, and immune response.11

MEDICAL CANNABIS LEGALIZATION

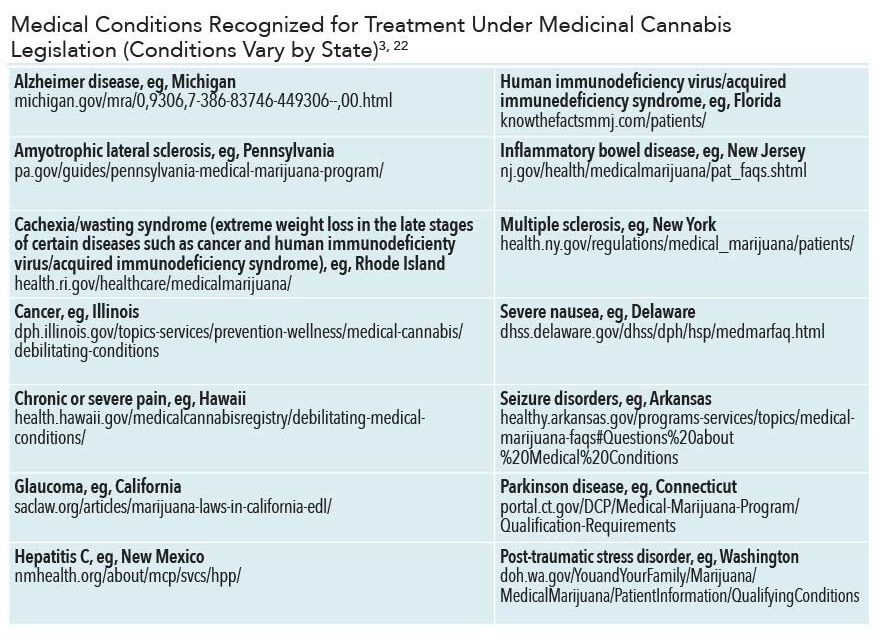

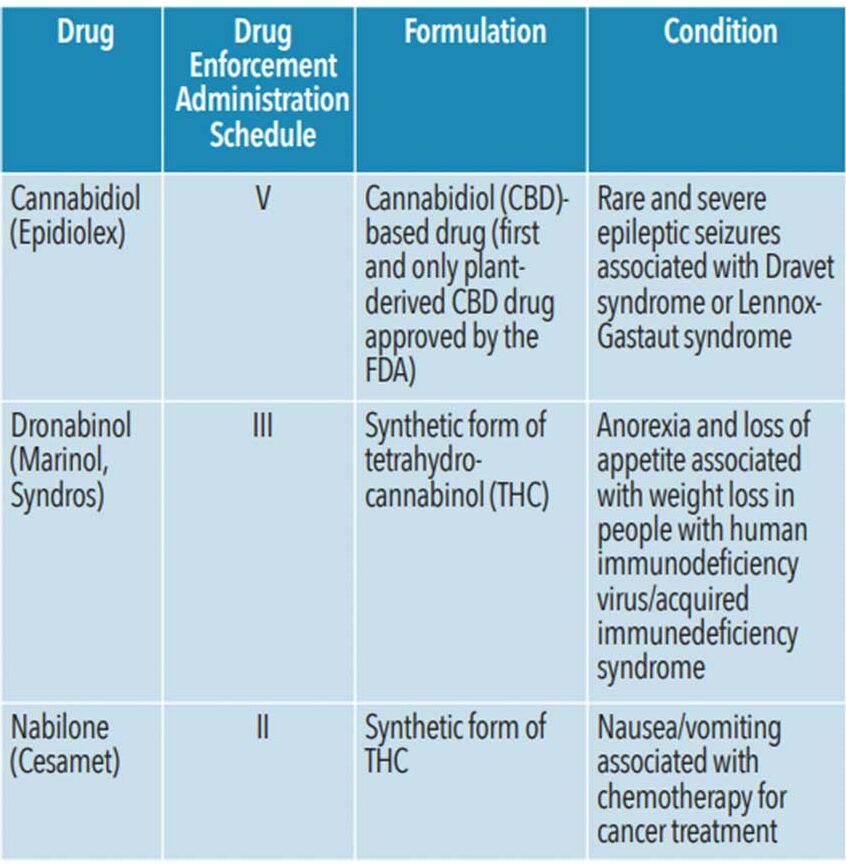

The legalization of cannabis use for both medical and recreational uses is growing across the US. However, much remains unknown about the drug. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has not approved the whole cannabis plant for use as medicine.7 However, the cannabinoids (CBD, THC) that have been isolated from the plant are used in select drugs approved by the FDA for limited therapeutic uses, including seizures, weight loss associated with human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), and nausea associated with cancer treatments (Table 1).12

While whole cannabis remains a Schedule I narcotic (defined as having “no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse”) under the US Controlled Substance Act, its cannabinoids are scheduled separately from whole cannabis.13 For example, dronabinol (synthetic form of THC), is classified as a Schedule III drug (“having moderate to low potential for physical and psychological dependence) and is available with a prescription.12,13 However, FDA-approved cannabinoid drugs are quite different from cannabis obtained from state-certified dispensaries.

Though whole cannabis supply and use remain illegal at the federal level, individual states may have their own laws.14 Starting in the late 1990s, states began passing laws to protect individuals who use cannabis for medical purposes. As of November 2020, 36 states have legalized marijuana for medicinal use and 15 states have legalized marijuana for recreational use.15 As of spring 2020, approximately 4.3 million people used medical cannabis in states where cannabis is legal.3

Despite a scarcity of well-designed research to support cannabis’ safety and efficacy, many states allow its use for a variety of conditions.14,16 Modern therapeutic uses of CBD range from treating nausea, pain, and inflammation to various skin conditions such as eczema and psoriasis. CBD may also reduce seizure frequency in individuals with Dravet syndrome or Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. THC successfully reduces nausea and vomiting among individuals undergoing chemotherapy, and increases appetite in individuals affected by wasting associated with late stages of cancer and AIDS.17 Medical cannabis may also improve muscle spasticity and pain in those with multiple sclerosis and other neurological conditions; reduce intraocular pressure in individuals with glaucoma; and improve symptoms of anxiety, depression, insomnia, and post-traumatic stress disorder.16,17 Cannabis use may also help individuals recover from opioid use disorder but research has yet to show a direct association.8

ROUTES OF ADMINISTRATION

Oral health professionals should understand the increasingly diverse routes of administration and the potential for adverse effects on oral health. In the US, smoking and vaporizing combusted cannabis materials by way of a joint, blunt, spliff, pipe, water pipe, or bong remains the most common route of administration for both medicinal and recreational use. Water pipes and bongs are intended to reduce inhalation of toxins by filtering the combusted cannabis smoke through water, however, it is unknown how effective this is.1 The psychoactive effects from smoked cannabis in any form are seen within minutes of administration and can last several hours.18

Vaporization, or cannavaping, has become a popular inhalation-based route of administration. A vape pen or e-cigarette is used to electronically heat cannabis to high enough temperatures to release its active cannabinoids along with water vapor as an aerosolized mixture that is inhaled.1 The addition of vitamin E acetate in some cannabis, nicotine, and other vaping products has led to safety concerns as it has been implicated in more than 2,800 cases of lung injury and death in the US as of February 2020.19 The practice of dabbing has also become popular and refers to the inhalation of flash-vaporized cannabis from concentrated resins. Some data suggest that dabbing increases the severity of effects and raises the risk for burns.1,12

Alternatives to inhalation-based cannabis include edibles such as cannabis-infused foods, drinks, and candies. Edibles provide a delayed onset of psychoactive effects due to their lag in bioavailability. These effects can be unpredictable, long-lasting, and potentially overwhelming, especially as patients may have difficulty in titrating doses.

Liquid tinctures provide another oral route for users. They contain alcohol-based liquid cannabis extracts administered as drops and absorbed through the oral mucosa. Strips, sprays, lozenges, and capsules are among other oral routes of ingestion; current data on the prevalence of their use is limited.1

Cannabis’ active compounds can also be administered through topical application to the skin. Transdermal patches allow controlled delivery of cannabinoids into the bloodstream and are currently being studied for use in patients with arthritis.20,21 Cannabis-infused lotions, creams, balms, and oils may be used in the localized management of skin conditions including eczema and psoriasis. Vaginal and rectal suppositories are being evaluated for medicinal applications such as endometriosis and hemorrhoids.1

GENERAL HEALTH CONSIDERATIONS

Research is ongoing to determine cannabis’ effects on general health. THC is likely responsible for the majority of its adverse health effects.5 Higher THC concentrations can cause orthostatic hypotension and self-limited tachycardia. THC can cross the placenta during pregnancy and may be secreted in breast milk. Cannabis use during pregnancy may be associated with low birth weight in infants.22 Short-term exposure to smoking cannabis may be linked to bronchodilation, while long-term effects may include lower forced expiratory volume and increased risk for respiratory infections.14 Current evidence does not demonstrate an independent connection between cannabis use and an increased risk for lung cancer, but associated risk factors should not be discounted.1,14 Clinically observed effects of acute cannabis intoxication from THC may include impairments in memory and attention and cause acute dizziness, fatigue, disorientation, euphoria, and hallucinations.14,23

ORAL HEALTH IMPLICATIONS OF CANNABIS USE

Research regarding cannabis use and its impact on oral health is still limited. However, some associations with oral effects—such as xerostomia, caries, periodontal diseases, and oral cancer—have been found.17,24,25 Oral health professionals should be able to discuss the possible implications of medical cannabis use in order to better support patients’ oral and overall health.

Regardless of route of administration, cannabis use may impact salivary flow due to its interaction with the parasympathetic nervous system.25 This can lead to xerostomia during and immediately after use for up to several hours.24 THC is an appetite stimulant that may lead users to consume cariogenic foods. When combined with poor oral hygiene, individuals experiencing dry mouth may be at greater risk for caries.19,24

Some evidence suggests an association between frequent cannabis use via inhalation and gingivitis, periodontal diseases, oral lesions, and infection.14,23,26,27 A study by Rawal et al2 concluded that chronic marijuana use may be associated with gingival enlargement, appearing clinically similar to phenytoin-induced enlargement. Further research is needed on this subject.

Inhaling cannabis is the most hazardous to oral health, as the user is exposed to higher concentrations of carcinogens than tobacco, and may raise the risk for oral cancer. More evidence is required to establish an independent relationship between oral cancers and cannabis use.24

Some studies have found associations but not causal effects between the human papillomavirus (HPV) and marijuana use.28 A 2020 study found that THC in the bloodstream may accelerate the growth of biomarkers associated with HPV-related head and neck cancers.29

CONSIDERATIONS IN PATIENT MANAGEMENT

When assessing and treating patients who use cannabis, a patient’s ability to provide consent, impact of cannabis use on oral health, and potential interactions with anesthetics and prescribed medications should all be considered.18,30 Maintaining good rapport with patients who use cannabis can help ensure that treatment and education are geared toward their specific needs.24

Determining whether a patient is a cannabis user is important to providing accurate treatment and education. Incorporating questions regarding cannabis use into the medical history, along with asking follow-up questions, can be helpful. Relevant information may include patient usage, dosing strategies, routes of administration, dietary habits, and oral implications.

Self-reporting of medical cannabis use can still be compromised due to stigma or legal status in the state in which treatment is provided. Asking questions about most recent cannabis usage and evaluating physical signs are important to determine if a patient can give consent for treatment. Considerations for informed consent are similar to those for patients who consume alcohol or use prescription medications that can cause impairment.24,30 Implementing office policies and procedures can help oral health professionals objectively determine when rescheduling a patient is appropriate. Signs and symptoms of cannabis use that may be noted during the initial assessment may include bloodshot or glassy eyes, dilated pupils, tachycardia, hypertension, lethargy, anxiety, confusion, or difficulty focusing.18,31 Oral cancer screenings should be part of routine preventive dental assessments. Of note should be changes to soft tissue and oral epithelium, including gingival enlargement and stomatitis.

Intraoral considerations, most often associated with long-term and frequent cannabis use, include increased bleeding, xerostomia, and delayed healing, which can complicate treatment.18,30 Even if a patient is deemed suitable for treatment, the physiological effects of frequent cannabis use can be prolonged over multiple days due to the body’s slow excretion of the drug.16 Patients may need to be placed in a semi-supine position as orthostatic hypotension may occur, posing a risk for falling or fainting.9 Cannabis users may also experience tachycardia and increased anxiety as a side effect of THC; these effects may be heightened or prolonged with local anesthetics that contain epinephrine, which can be potentially life threatening.23,30 Consider postponing nonemergency treatment and use caution when administering anesthesia with epinephrine to patients who regularly or have recently used cannabis.16

Another consideration is potential drug interactions. A consultation with the patient’s primary care physician may be necessary. Cannabis is generally well-tolerated, but there is little high-level research directly assessing its drug-to-drug interactions. THC and CBD may affect a drug’s absorption, distribution, metabolism, or excretion. The interaction is uniquely influenced by the drug in question and the nature of the cannabis preparation used.16

Oral health professionals need to maintain a nonjudgmental attitude toward patients who disclose their medical cannabis use.24 Patient education can include general and oral health risks, diet, and oral self-care techniques. As inhalation of cannabis has been shown to be the most hazardous route of administration, less harmful methods could be discussed. As with tobacco smokers, the negative pressure created by the act of inhaling cannabis can be hazardous to post-operative surgical healing, increasing the potential for dry sockets. Clinicians should use their best judgment to determine what should be discussed, as education needs may vary based on the patient’s frequency of medical cannabis use and routes of administration.

As with any drug use, documentation is important. Documenting dose and frequency of a patient’s cannabis use and observations of his or her ability to provide consent on the patient’s medical history is key in addition to whether the patient was impaired and unable to consent for treatment. Note any oral health considerations that may be associated with cannabis use, and document information that was shared with the patient.18,30

CONCLUSION

Cannabis use effects both general and oral health but more research is needed to determine additional impacts on health. Potential therapeutic benefits of medical cannabis are becoming better understood; however, cannabis has yet to undergo rigorous drug-approval processes to assure its safety and efficacy as a medical therapy. As research becomes available, oral health professionals should remain up-to-date on current laws, medicinal uses, general and oral health implications, and patient management strategies.

REFERENCES

- Russell C, Rueda S, Room R, et al. Routes of administration for cannabis use—basic prevalence and related health outcomes: a scoping review and synthesis. Int J Drug Policy. 2018;52:87–96.

- Rawal SY, Tatakis DN, Tipton D. Periodontal and oral manifestations of marijuana use. J Tenn Dent Assoc. 2012;92:26.

- Marijuana Policy Project. Medical Marijuana Patient Numbers. Available at: mpp.org/issues/medical-marijuana/state-by-state-medical-marijuana-laws/medical-marijuana-patient-numbers/. Accessed March 8, 2021.

- Schauer GL, King BA, Bunnell RE, et al. Toking, vaping, and eating for health or fun: marijuana use patterns in adults, US, 2014. Am J Prev Med. 2016;50:1–8.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Marijuana and Public Health. Available at: cdc.gov/marijuana/index.htm. Accessed March 8, 2021.

- Levinsohn EA, Hill KP. Clinical uses of cannabis and cannabinoids in the United States. J Neurol Sci. 2020;411:1–6.

- United States Food and Drug Administration. FDA Regulation of Cannabis and Cannabis-Derived Products, Including Cannabidiol (CBD). Available at: fda.gov/news-events/public-health-focus/fda-regulation-cannabis-and-cannabis-derived-products-including-cannabidiol-cbd. Accessed March 8, 2021.

- Small E. Evolution and classification of Cannabis sativa (marijuana, hemp) in relation to human utilization. Bot Rev. 2015;81:189–294.

- National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. Cannabis (Marijuana) and Cannabinoids: What You Need to Know. Available at: nccih.nih.gov/health/marijuana-cannabinoids. Accessed March 8, 2021.

- VanDolah HJ, Bauer BA, Mauck KF. Clinicians’ guide to cannabidiol and hemp oils. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94:1840–1851.

- Witkamp R, Meijerink J. The endocannabinoid system: an emerging key player in inflammation. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2014;17:130–138.

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. Marijuana as Medicine. Available at: drugabuse.gov/publications/drugfacts/marijuana-medicine. Accessed March 8, 2021.

- United States Drug Enforcement Administration. Drug Scheduling. Available at: dea.gov/drug scheduling#:~:text=Schedule%20III%20drugs% 2C%20substances%2C%20or,but%20more%20than%20Schedule%20IV. Accessed March 8, 2021.

- Ebbert JO, Scharf EL, Hurt RT. Medical cannabis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2018;93:1842–1847.

- National Conference of State Legislatures. State Medical Marijuana Laws. Available at: ncsl.org/research/health/state-medical-marijuana-laws.aspx. Accessed March 8, 2021.

- Bridgeman MB, Abazia DT. Medicinal cannabis: history, pharmacology, and implications for the acute care setting. P T. 2017;42:180–188.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. The health effects of cannabis and cannabinoids: the current state of evidence and recommendations for research. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; January 12, 2017.

- Martin M. Impaired in the chair? Cannabis and the dental hygiene process of care. Available at: files.cdha.ca/Profession/OhCanada/OhCanada_Winter_cannabis.pdf. Accessed March 8, 2021.

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Smoking and Tobacco Use, Outbreak of Lung Injury Associated With the Use of E-cigarette, or Vaping, Products. Available at: cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/severe-lung-disease.html#key-facts. Accessed March 8, 2021.

- Brooke LL, Herrmann CC, Yum S, inventors; Brooke LL, Herrmann CC, Yum S; assignee. Cannabinoid patch and method for cannabis transdermal delivery. United States patent. Available at: patents.google.com/patent/US6328992B1/en. Accessed March 8, 2021.

- Bruni N, Della Pepa C, Oliaro-Bosso S, et al. Cannabinoid delivery systems for pain and inflammation treatment. Molecules. 2018;23:2478.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Marijuana use during pregnancy and lactation. Committee Opinion No. 722. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e205–209.

- Whiting PF, Wolff RF, Deshpande S, et al. Cannabinoids for medical use: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2015;313:2456–2473.

- Joshi S, Ashley M. Cannabis: a joint problem for patients and the dental profession. Br Dent J. 2016;220:597–601.

- Versteeg PA, Slot DE, Van Der Velden U, et al. Effect of cannabis usage on the oral environment: a review. Int J Dent Hyg. 2008;6:315–320.

- Chisini LA, Cademartori MG, Francia A, et al. Is the use of cannabis associated with periodontitis? a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Periodontal Res. 2019;54:311–317.

- Ortiz AP, González D, Ramos J, et al. Association of marijuana use with oral HPV infection and periodontitis among Hispanic adults: implications for oral cancer prevention. J Periodontol. 2018;89:540–548.

- Gillison ML, D’Souza G, Westra W, et al. Distinct risk factor profiles for human papillomavirus type 16-positive and human papillomavirus type 16-negative head and neck cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:407–420.

- Liu C, Sadat SH, Ebisumoto K, et al. Cannabinoids promote progression of HPV-positive head and neck squamous cell carcinoma via p38 MAPK activation. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26:2693–2703.

- American Dental Association. Cannabis: Oral Health Effects. Available at: ada.org/en/member-center/oral-health-topics/cannabis. Accessed March 8, 2021.

- Dhingra D, Kaur S, Ram J. Illicit drugs: effects on eye. Indian J Med Res. 2019;150:228–238.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. April 2021;19(4):36–39.