ROSTISLAV_SEDLACEK / ISTOCK / GETTY IMAGES PLUS

ROSTISLAV_SEDLACEK / ISTOCK / GETTY IMAGES PLUS

Oral Effects of Eating Disorders

Spotting the signs of these issues and helping to mitigate their impact on the oral cavity are key to supporting both oral and systemic health.

This course was published in the April 2022 issue and expires April 2025. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Describe the prevalence of eating disorders.

- Define anorexia nervosa, bulimia, rumination syndrome, and pica.

- Identify the oral manifestations associated with different types of eating disorders.

- Discuss the role of the dental hygienist in managing patients with eating disorders.

Oral health professionals are well positioned to identify early signs of eating disorders and refer patients to the appropriate healthcare professionals.1 Understanding how to recognize the oral implications and manifestations of eating disorders and how to implement appropriate screening tools are critical in helping patients receive the treatment required for recovery.

Approximately 30 million individuals in the United States develop an eating disorder at some point in their lives.2 Eating disorders are serious but treatable mental and physical illnesses that can affect individuals of any gender, age, race, sexual orientation, and physique. Although the precise etiology of eating disorders remains unknown, biological, psychological, and sociocultural factors play a role.2

Eating disorders can have deleterious effects on oral health, as oral hygiene may suffer in the midst of depression, and eating disorder behavior, such as purging, hinders oral health. Medication regimens that address eating disorder comorbidities may also cause oral side effects. The interprofessional team treating patients with these disorders needs to recommend professional oral healthcare for this group.3

Individuals with eating disorders often experience poorer systemic and oral health than those without eating disorders.4 Currently, limited collaborative interaction exists among dental professionals and eating disorder professionals, such as psychiatrists, nutritionists, and physicians. Addressing oral disease among individuals with eating disorders is necessary. Oral health professionals play a crucial role in helping those experiencing eating disorders by providing preventive and therapeutic oral healthcare.3

Clinical Manifestations

Identifying and caring for the oral signs of eating disorders are the purview of oral health professionals in addition to referring patients to appropriate medical professionals.5 Disordered eating behaviors and nutritional deficiencies elevate the risk for oral disease.3

Anorexia nervosa. Patients affected by eating disorders often experience compensatory behaviors to manage their weight.6 Anorexia nervosa is characterized by an exaggerated fear of gaining weight that leads to distorted body image and a too-low body weight accomplished by starvation or overexercising. Individuals with anorexia often obsessively control the number of calories consumed and the types of food they eat. Some individuals exercise obsessively, self-induce vomiting, use laxatives, and/or binge eat.7

Bulimia nervosa. This eating disorder is categorized by binge eating followed by compulsory behaviors to prevent weight gain, such as self-induced vomiting or purging, overexercising, and fasting.8

Both anorexia and bulimia can be life-threatening disorders that require professional treatment. In regards to oral health, self-induced vomiting can permanently harm tooth enamel. This population may present with noninflammatory salivary gland swelling. At times, the parotid gland and submandibular gland may protrude, altering the facial profile. This gland swelling may appear unilaterally or bilaterally.6 The pathogenesis of this side effect may include increased carbohydrate intake, gastric content irritation, and malnutrition.9 Self-induced vomiting appears to be associated with the onset of the swelling, often beginning 2 days to 6 days after the compensatory episode.6 This behavior may also alter the esophageal mucosa, causing dryness and ulcerations. Additional effects include diminished taste acuity, dehydration, enamel erosion, dentinal hypersensitivity, traumatic ulcerations, hematomas, and cheek and lip biting.10

Rumination syndrome and pica. Rumination syndrome is a functional gastrointestinal disorder characterized by unforced and repetitive regurgitation of newly ingested food from the stomach to the oral cavity accompanied by either re-swallowing or spitting.11 Although rumination syndrome was originally linked to individuals with delays or impairments in mental development, it is now recognized as a separate clinical entity.11 Rumination syndrome can cause psychological distress and health problems, such as malnutrition, weight loss, electrolyte disturbances, caries, erosion, and oral malodor.12

Pica is the repeated consumption of “nonnutritive, nonfood” matters, such as dirt, chalk, or paper. To be considered pica, these actions must last more than 1 month, be developmentally unsuitable, and not be part of a cultural practice. Pica is difficult to detect, as it may not be identified until serious health consequences occur. Health problems induced by pica include heavy metal toxicity, gastrointestinal obstruction, parasitic infection, and dental problems, such as caries, erosion, abrasion, and fractured teeth.12

Rumination syndrome and pica are less pervasive than anorexia and bulimia, and more research is needed on these conditions.13

Oral Implications

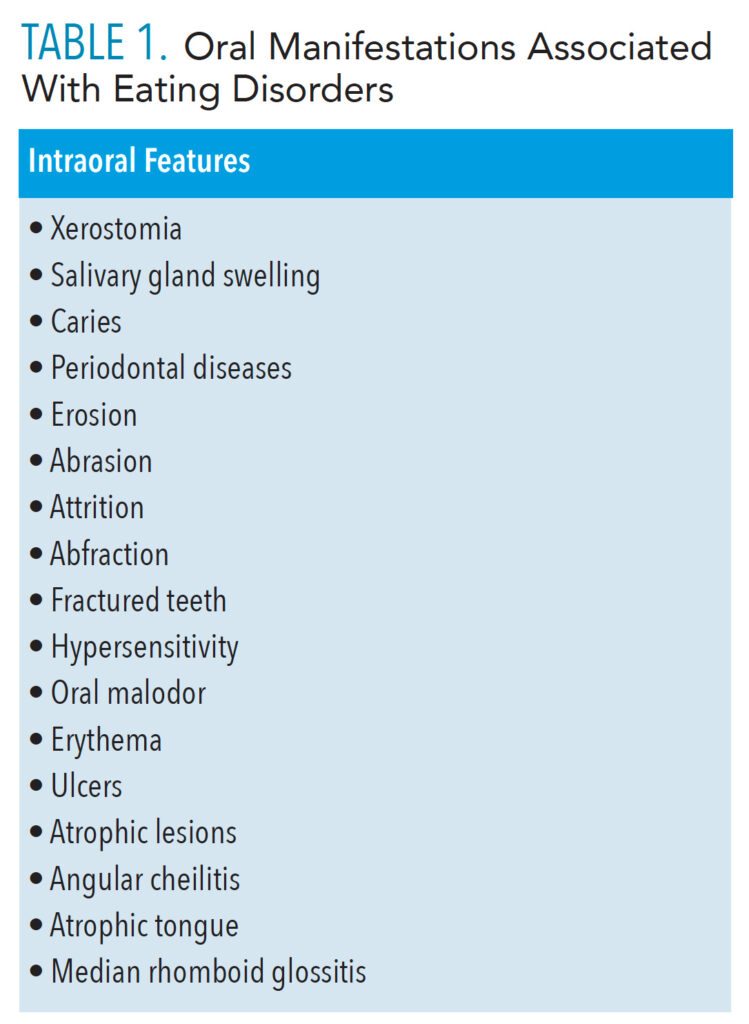

Individuals with eating disorders are at increased risk for poor oral health. The changing severity of oral disease may be associated with the fluctuations in behavior patterns, unhealthy diet, and poor oral hygiene.12 Oral implications from eating disorders, such as enamel erosion, dental caries, periodontal diseases, damage to the gingival tissues, and xerostomia, may remain undetected for years (Table 1).3 Due to the oral health effects caused by eating disorders, dentists and dental hygienists are often the first healthcare providers to identify the signs and symptoms of such health problems.14

Determining the etiology of multifactorial, noncarious lesions is important. Patients with eating disorders may exhibit bruxism as an involuntary reaction to emotions such as stress. Patients with anorexia or bulimia may present with erosive and abrasive changes in the oral cavity, which may cause attrition and abfraction.15 In patients with bulimia, oral acid levels are dependent on the type of food and drink ingested, purging behavior, and stomach acids transmitted to the oral cavity.16 Repeated exposure of the tooth structure to acids incurred by self-induced vomiting may cause demineralization, sensitivity, loss of tooth function, and tooth loss.3 Gastric acid in the oral cavity due to frequent regurgitation may affect the lingual surfaces of the maxillary anterior teeth. Erosion may progress to loss of tooth structure and dental anatomical features.17 Individuals with eating disorders typically select carbonated drinks with artificial sweeteners to control their appetite and weight, increasing the risk of erosion. Frequent toothbrushing has been observed in individuals with eating disorders, which can damage the tooth structure.16

Limited data are available on the association between anorexia and/or bulimia and periodontal health. Some studies show no difference in periodontal parameters among patients with eating disorders, while other studies report a higher prevalence of gingivitis, periodontitis, and gingival recession.4

Malnutrition and the use of medications commonly used in those with eating disorders can cause xerostomia. Xerostomia decreases the pH in the oral cavity, increasing caries and periodontal disease risk.3

The behavioral habits that accompany eating disorders may negatively impact the soft tissue in the oral cavity, such as erythema and ulcers on the soft palate and pharynx.18 Erythema and atrophic lesions may be caused by chronic irritation due to gastric fluids, especially among those who binge.9 Ulcerations may also be caused by trauma from mechanical irritation, such as the use of the fingers or objects to provoke vomiting. Additional effects on the soft tissue include dry lips and angular cheilitis. Angular cheilitis is associated with vitamin deficiencies, dehydration, low electrolytes, and general metabolic changes. Atrophic tongue and median rhomboid glossitis are also linked to eating disorders. Stress and anxiety accompanied by tooth clenching and temporomandibular pain can result in tongue indentations, such as crenated tongue.9,18

Individuals with eating disorders may use substances, such as cigarettes, to suppress appetite, which may result in smoking-related oral tissue lesions. Although smokers present with increased soft tissue lesions, the majority of patients with eating disorders—regardless of smoking status—present with these findings.9,18

Eating disorders alter patients’ oral, nasal and pharyngeal areas, including oral mucosal changes and dental lesions, prompted by both local and systemic factors.9 Oral health professionals may suspect an eating disorder based on characteristic clinical manifestations, and thus should provide referrals to appropriate healthcare providers. Early detection of eating disorders is crucial to preventing health complications.

Screening Tools to Identify Eating Disorders

Eating disorder screening tools can be easily adopted in the dental setting, paving the way for patient education and intervention. Ensuring that patients are comfortable is key before addressing the signs and symptoms of eating disorders. Additionally, social, demographic, and psychiatric factors are all necessary to consider when making an assessment.1

The SCOFF screening tool is widely used to identify eating disorders. SCOFF is an acronym delineating five significant screening questions that can be remembered through the mnemonic, “Sick, Control, One Stone, Fat, and Food.” The questions are as follows:

- Do you make yourself sick because you feel uncomfortably full?

- Do you worry you have lost control over how much you eat?

- Have you recently lost more than one stone (14 pounds) in a 3-month period?

- Do you believe yourself to be fat when other say you are too thin?

- Would you say that food dominates your life?

A yes response equals one point. Two or more points indicates the presence of an eating disorder.19,20

Including tooth wear indices as a component of the medical history and dental examination can help detect eating disorders. Examples of tooth erosion indices include: Lussi’s index-modified version of Linkosalo and Markkanen index, Tooth Wear Index modified by de Carvahalo Sales-Peres et al, BEWE (Basic Erosive Wear Examination), and the Olio et al index.15

The Lussi’s index-modified version of Linkosalo and Markkanen index assesses dentin exposure. The Tooth Wear Index modified by de Carvahalo Sales-Peres et al examines tooth wear via a grade. The BEWE assesses teeth by sextants, categorizing risk level and providing specific treatment for each category. The Olio et al index measures occlusal wear.15

Clinical Intervention

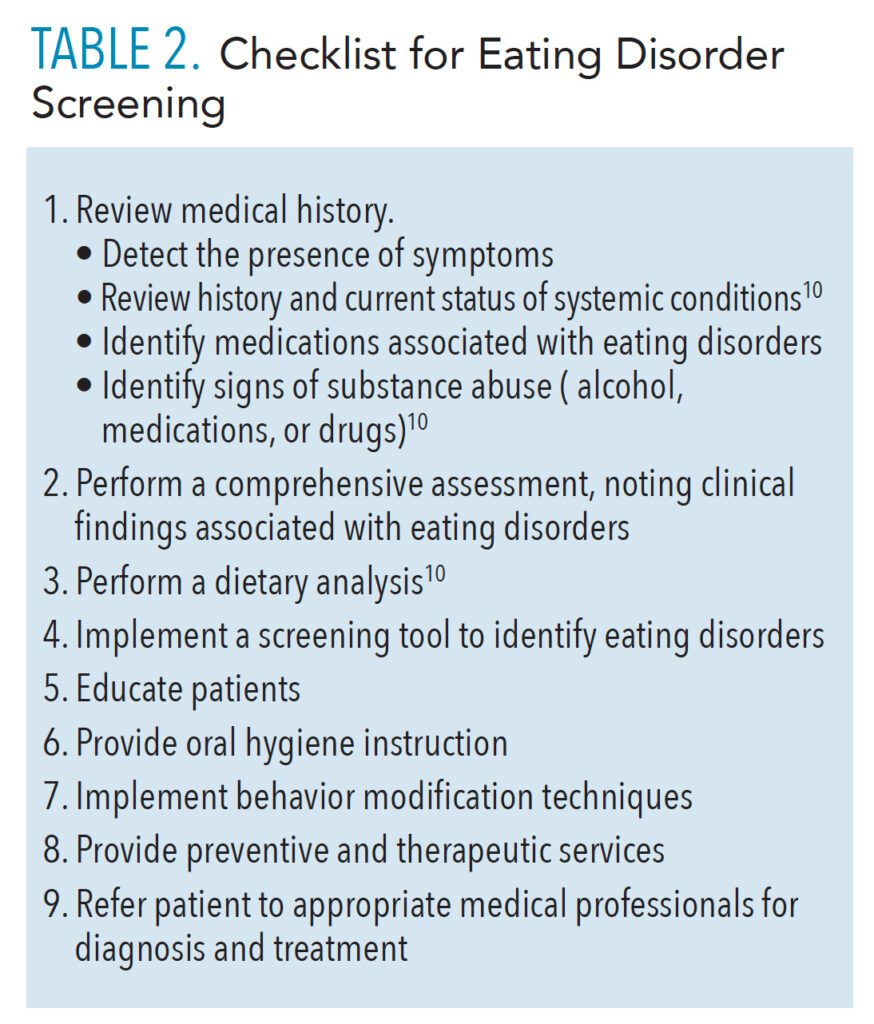

Dental hygienists and dentists play a crucial role in disease detection and prevention (Table 2). Treatment plans for patients suspected of or with known eating disorders should focus on intervention and referral. Interventions focusing on education and treatment are necessary for optimal patient management. Evidence-based strategies individualized to each patient should be selected according to the oral health professional’s assessment. Referring patients to the appropriate medical specialist is key for facilitating a diagnosis and treatment of the nonoral problems related to these disorders.

Patients with swelling of the parotid gland need to understand the etiology of this condition. In these cases, the parotid gland is over stimulated and produces excess saliva in response to increased vomiting. Education is a key factor in addressing this issue. Patients should be informed that, in most instances, the parotid gland will revert to its previous size and normal function if self-induced vomiting is ceased.

Treatment strategies for xerostomia should focus on reducing symptoms, increasing salivary flow, and preventing complications.21,22 Patients should remain well hydrated, avoid irritating dentifrices and foods, use sugar-free gum or candy, and brush with a fluoride dentifrice. The use of mucosal lubricants, saliva substitutes, and salivary stimulants are also viable treatment options.21

Patients at high caries risk should be informed about their risk factors, including those unrelated to eating disorders. Treatment options include brushing with a fluoride dentifrice, prescribing a fluoride rinse or gel, applying fluoride varnish, addressing oral self-care issues, reducing consumption of cariogenic foods, and instituting frequent recare appointments. Restorative treatment should be recommended in cases of existing nonreversible caries lesions.

A comprehensive periodontal assessment should also be performed. Although it may be difficult to link periodontal diseases to eating disorders, periodontal status should always be classified according to the American Academy of Periodontology’s 2018 classification system. Treatment planning should include patient-specific interventions.

Treatment methods for oral malodor include mechanical and chemical reduction of microorganisms and chemical neutralization of volatile sulfur compounds.23 Most important, caries lesions and periodontal infections must be treated. Tongue scraping and interdental aids, such as floss, can reduce the presence of oral pathogens. The use of antimicrobials, such as chlorhexidine, cetylpyridinium chloride, and triclosan, may also reduce the bacterial load. Mouthrinses containing chlorine dioxide and zinc may neutralize the sulfur compounds that cause oral malodor.23

To diminish the negative impact of tooth erosion, dietary counseling should be implemented. Recommendations should be made to improve salivary flow, neutralize pH levels in the oral cavity, and ensure fluoride exposure. Noncarious cervical lesions may also affect those with eating disorders. Toothbrushing habits should be reviewed among those with abrasion. Occlusion should be assessed for those with abfraction and wear facets. Although there is minimal evidence demonstrating the efficacy of nightguards and bite splints, these oral appliances may be considered. In all cases, the patient should be educated about etiologic factors of the loss of tooth structure and referred to appropriate medical professionals, if necessary. If patients understand the damage caused by their eating disorders, they may be more inclined to seek help to stop the behavior.

As mucosal changes and oral lesions associated with eating disorders are related to local irritating and systemic factors,9 professional considerations should focus on education. Patients should be informed that self-induced vomiting or eating nonfood materials could irritate or damage the hard and soft palates, dorsal surface of the tongue, and lips.9 Patient education should focus on reducing behaviors that induce hemorrhagic lesions and oral atrophies as well as addressing nutritional deficiencies. Smoking cessation efforts should also take place.

Conclusion

Oral health professionals need to obtain the appropriate knowledge and skill set to recognize the signs and symptoms of eating disorders. The use of screening tools can help identify such conditions. Patient management should include behavior modification techniques, education, and provision of preventive and therapeutic services. Additionally, implementing an interprofessional approach by referral to appropriate medical professionals is crucial to address issues outside of the dental hygiene scope of practice.

References

- American Dental Association. Statement from Richard W. Gesker, DDS, Dentists can help spot early signs of eating disorders. Available at: ada.org/en/publications/ada-news/떑-archive/november/dentists-can-help-spot-early-signs-of-eating-disorders. Accessed March 21, 2022.

- National Eating Disorders Association. What Are Eating Disorders? Available at: nationaleatingdisorders.org/what-are-eating-disorders. Accessed March 21, 2022.

- Johnson LB, Boyd LD, Rainchuso L, Rothman A, Mayer B. Eating disorder professionals’ perceptions of oral health knowledge. Int J Dent Hyg. 2017;15:164–171.

- Pallier A, Karimova A, Boillot A, et al. Dental and periodontal health in adults with eating disorders: a case-control study. J Dent. 2019;84:55–59.

- Frimenko KM, Murdoch-Kinch CA, Inglehart MR. Educating dental students about eating disorders: perceptions and practice of interprofessional care. J Dent Educ. 2017;81:1327–1337.

- Colella G, Lo Giudice G, De Luca R, et al. Interventional sialendoscopy in parotidomegaly related to eating disorders. J Eat Disord. 2021;9:25.

- National Eating Disorders Association. Anorexia Nervosa. Available at: nationaleatingdisorders.org/learn/by-eating-disorder/anorexia. Accessed March 21, 2022.

- National Eating Disorders Association. Bulimia Nervosa. Available at: nationaleatingdisorders.org/learn/by-eating-disorder/bulimia. Accessed March 21, 2022.

- Panico R, Piemonte E, Lazos J, Gilligan G, Zampini A, Lanfranchi H. Oral mucosal lesions in anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and EDNOS. J Psychiatr Res. 2018;96:178–182.

- Glassford L, MacDonald LL. Eating disorders. In: Bowen DM, Pieren JA, eds. Darby and Walsh Dental Hygiene: Theory and Practice. 5th ed. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier; 2020:902–916.

- Absah I, Rishi A, Talley NJ, Katzka D, Halland M. Rumination syndrome: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2017;29:10.

- Delaney CB, Eddy KT, Hartmann AS, Becker AE, Murray HB, Thomas JJ. Pica and rumination behavior among individuals seeking treatment for eating disorders or obesity. Int J Eat Disord. 2015;48:238–248.

- Murray HB, Thomas JJ, Hinz A, Munsch S, Hilbert A. Prevalence in primary school youth of pica and rumination behavior: The understudied feeding disorders. Int J Eat Disord. 2018;51:994–998.

- Rungta N, Kudpi R. Evaluation of eating disorders using “SCOFF Questionnaire” among young female cohorts and its dental implications—an exploratory study. J Orofac Sci. 2019;11:27.

- Zalewska I, Trzcionka A, Tanasiewicz M. A comparison of etiology-derived and non-etiology-derived indices utilizing for erosive tooth wear in people with eating disorders. the validation of economic value in clinical settings. Coatings. 2021;11:471.

- Johansson AK, Norring C, Unell L, Johansson A. Diet and behavioral habits related to oral health in eating disorder patients: a matched case-control study. J Eat Disord. 2020;8:7.

- AlShahrani MT, Haralur SB, Alqarni M. Restorative rehabilitation of a patient with dental erosion. Case Rep Dent. 2017;2017:9517486.

- Garrido-Martínez P, Domínguez-Gordillo A, Cerero-Lapiedra R, et al. Oral and dental health status in patients with eating disorders in Madrid, Spain. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2019;24:e595–e602.

- Solmi F, Hatch SL, Hotopf M, Treasure J, Micali N. Validation of the SCOFF questionnairefor eating disorders in a multiethnic general population sample. Int J Eat Disord. 2015;48:312–316.

- Sharifian MJ, Pohjola V, Kunttu K, Virtanen JI. Association between dental fear and eating disorders and body mass index among Finnish university students: a national survey. BMC Oral Health. 2021;21:93.

- Villa A, Connell CL, Abati S. Diagnosis and management of xerostomia and hyposalivation. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2014;11:45–51.

- American Dental Association. Xerostomia. Available at: ada.org/resources/research/science-and-research-institute/oral-health-topics/xerostomia. Accessed March 21, 2022.

- Kapoor U, Sharma G, Juneja M, Nagpal A. Halitosis: Current concepts on etiology, diagnosis and management. Eur J Dent. 2016;10:292–300.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. April 2022;20(4):38-41.