Mastering Upper Body Mechanics

Correct grasp, neutral positioning of the upper extremities, and hand, wrist, and forearm relationships are crucial to preventing repetitive strain injuries.

Dental hygiene practice has shifted toward an ergonomic focus with new operator stool designs that include arm rests, magnification loupes that improve visibility while optimizing posture, and new instrument handles with scoring patterns and larger diameter handles. While such devices may prove helpful in preventing musculoskeletal disorders—namely repetitive strain injuries—none of these devices will help if good body mechanics, ie, neutral positioning of the upper body and extremities, are not routinely practiced.

THE GRASP

Dental hygiene instruments are usually small in diameter, thus requiring a pinch-grip pressure to control them. This can lead to stress of the forearm, tendons, and wrist.1 The hand is four times stronger when assuming a grip position than when in a pinch position. This suggests that four to five times as much muscle and tendon force is required to pinch an instrument than to grip it.2 To prevent the increased stress on the wrist and forearm tendons due to pinch force, a correct modified pen grasp must be maintained (Figures 1 and 2).

The fingers should produce a triangular, tripod effect. The bony side of the pad of the middle finger close to the fingernail is placed on the shank of the instrument. The index finger is bent at the second joint (counted from fingertip) and is positioned above the middle finger on the same side of the handle. The pad of the thumb is placed midway between the middle and index fingers on the opposite side of the handle. As Figure 1 illustrates, a “tripod” is formed between the pads of the index and middle fingers and the pad of the thumb.3 To further reduce pinch grip force, incorporate larger diameter handles in the instrument set-up. Larger diameter handles help reduce the pinching effect and distribute forces over a larger area.4

UPPER BODY POSTURE

Correct operator posture must also be maintained, with an emphasis on neutral positioning of the upper extremities (Figure 3). Ergonomists have concluded through observational studies that deviations from neutral posture over a long period of time, as well as the performance of repetitive tasks required in the practice of dental hygiene, can result in musculoskeletal disorders.5,6 When assuming correct posture, the back, neck, and head are aligned along a straight axis.7 Maintain this neutral positioning whenever possible. Every effort must be made to avoid bending or twisting in order to obtain direct or indirect vision.

Awareness of your upper body position is important because adjustments during the delivery of care may prevent the development of bad postural habits. Berry et al8 found that the longer hygienists are in practice, the more likely they will unconsciously assume improper body positions. If guidelines for maintaining optimal position are followed, musculoskeletal problems may be prevented. Following are suggested guidelines:

1. Center body weight on the stool with the back in a neutral position, back against stool, shoulders relaxed (Figure 3).

2. Stool height needs adjustment for the individual operator. Sit with the rear as far back in the chair as possible, the knees slightly below the level of the hips. Weight will be evenly distributed over the back of the thighs. Legs should form a tripod with the long axis of the body (Figure 4).

3. Plant feet firmly on the floor. It is not always necessary to have them both flat on the ground. From time to time, foot position may be varied to give different back muscles a rest. One foot should always be flat on the floor to maintain stability. Do not cross the legs.

4. Adjust the stool’s backrest to provide lumbar support.

5. Shoulders should be consciously relaxed any time tension is felt. To help maintain a relaxed shoulder position, the elbows should be approximately even with the occlusal plane of the instrumentation area. Adjust patient chair height if necessary.

6. An ideal distance of 14 to 16 inches should be maintained between patient and operator’s eyes without excessive bending of the neck. Magnification loupes may enhance vision without compromising posture.4

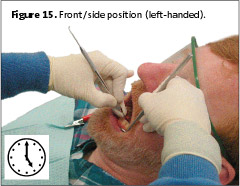

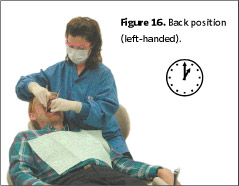

Guideline two is different from what has been historically taught on operator positioning in dental hygiene curricula. Here the upper body is assuming a tripod relationship with the legs. The clinician straddles the patient’s chair at all clock positions. Traditionally in a front position ( 8 o’clock, right-handed; 4 o’clock, left-handed), knees are kept together, making it difficult to place the clinician’s body close to the patient’s oral cavity. As a result, in order to reach the patient, the clinician must reach over with the body weight unevenly distributed over the hips and lower spine. The spine is no longer in a neutral position, often producing discomfort. The straddled operator position ensures upper body neutrality. Changing clinician technique, is a matter of awareness, re-education, and implementation.1

Table 1. Ergonomic products that are currently available.

Table 1. Ergonomic products that are currently available.

Repetitive strain injuries may also develop due to the following factors: increased static workload on small muscles and tendons of the fingers and hand and the flexion and extension positions of the wrist during repetitive scaling and polishing.1 To reduce static workload on the fingers and hand, use slow, deliberately applied force, allowing relaxation of the grasp between strokes rather than a rapid series of strokes with increased pinch force.4 The more precise the work, the greater the need for stability, control, and static muscle contraction.9 Rest periods are necessary to recover from the working stroke and muscle fatigue caused by static muscle contraction. Astrand and Rodahl10 suggest a ratio of 2:1 between contraction time and rest. Stretching fingers while reaching for another instrument may help in providing short periods of rest during patient care.

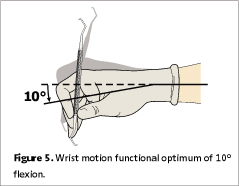

THE WRIST FACTOR

Neutral wrist position is crucial and should be maintained at all times. Laboratory studies supporting neutral positioning demonstrate increased pressure in the carpal tunnel from less than 5 mm Hg (pressure measurement) to more than 30 mm Hg (pressure measurement) during wrist flexion and extension.11 While in the neutral position, pressure in the carpal canal is lowest and the force placed on the flexor and extensor tendons is least.4 Avoid long periods of flexed or extended positions.

Figures 5 and 6 illustrate optimal ranges of wrist flexion and extension. Wrist motion should not exceed a functional optimum of 10° flexion to 35°of extension, when measured from the radius to the second metacarpal just below the index finger.4 More ergonomic practice includes limiting the use of digital motions by moving the entire hand, wrist, and forearm as a unit during the working stroke.3 Using the little finger extensor to balance the hand instead of keeping it tight against the ring finger and/or tucked under the grasp decreases pressure in the palm and carpal tunnel caused by isometric contraction.

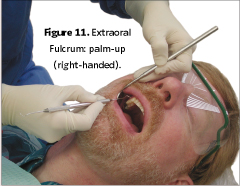

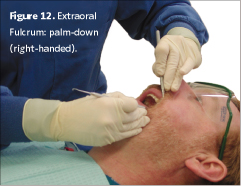

Avoid hyperextension of the thumb toward the palm (Figure 7).4 To keep neutral wrist position while maintaining neutral positioning of upper body extremities, adopt a straddled operator position and hand positions as illustrated in Figures 8, 9, and 10 for a right-handed clinician. Opposite arch fulcrums may help maintain a neutral wrist. Cross-over positions for sextant six (right-handed) and sextant four (left-handed), increase access to these areas with optimal, neutral wrist position. The use of extra-oral fulcrums, palm-up position for sextant one and palm-down for sextant three (right-handed clinician) is helpful in maintaining neutral position in maxillary posterior areas (Figures 11 and 12). Extra-oral fulcrums are opposite for a left-handed clinician (palm-up for sextant three and palm-down for sextant one).

SUMMARY

Along with using equipment that is ergonomic by design, the dental hygiene clinician must be willing to change working routines (ie, making necessary changes in grasp, positioning, and upper body mechanics) in the prevention of musculoskeletal disorders that could possibly end a dental hygiene career. Willingness to abandon bad postural habits and traditional techniques for those that foster better body mechanics and posture are steps in the right direction toward career longevity and prevention of repetitive strain injuries.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

I would like to thank Rita Charles for her help in preparing this manuscript and Kim Theesen, illustrator, for his assistance with the illustrations.

REFERENCES

- Liskiewicz ST, Kerschbaum WE. Cumulative trauma disorders: an ergonomic approach for prevention. J Dent Hyg. 1997;71:162-167.

- Armstrong TJ, Chaffin DB. Some biomechanical aspects of the carpal tunnel. J Biomech. 1979;12:567-570.

- Pattison AM, Pattison GL. Periodontal Instrumentation. 2nd ed. Norwalk, Conn: Appleton & Lange; 1992:137.

- Murphy DC. Ergonomics and the Dental Care Worker. Washington, DC: United Book Press Inc; 1998:175-176.

- Silverstein BA, Stetson DS, Keyserling WM, Fine LJ. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders: comparison of data sources for surveillance. Am J of Ind Med. 1997;31:600-608.

- Bramson JB, Smith S, Romagnoli G. Evaluating dental office ergonomic risk factors and hazards. J Am Dent Assoc. 1998;129:174-183.

- Goldman HS, Hartman KS, Messite J, eds. Occupational Hazards In Dentistry. Chicago: Year Book Medical Publishers; 1984:138.

- Barry RM, Woodall WR, Mahan JM. Postural changes in dental hygienists. Four-year longitudinal study. J Dent Hyg. 1992;65:147-150.

- Oberg T, Oberg U. Musculoskeletal complaints in dental hygiene: a survey study from a Swedish county. J Dent Hyg. 1993;67:257-261.

- Astrand PO, Rodahl K. Textbook of Work Physiology. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1986:115-126, 512-515.

- Gelberman RH, Herginroeder PT, Hargens AR, Lundborg GN, Akeson WH. The carpal tunnel syndrome. A study of carpal tunnel pressures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1981;63:380-383.

|

P R O D U C T S |

|

Color Coded Instruments • American Dental Medical Technology (ADMT), Spokane, Wash, offers ergonomically designed instruments. ADMT’s instruments are color coded to ensure quick differentiation, lightweight, and offer a variable diameter design. The instruments also offer custom marking. (888) 455-2368; www.admtechnology.com. |

|

Lightweight Telescopes • Designs for Vision Inc, Ronkonkoma, NY, provides dental telescopes that are lightweight and custom built. Designs for Vision measures each dental professional’s working distance and individually sets the focal length of the telescopes. The interpupillary distance and angle of declination are also individually set. (800) 345-4009; www.designsforvision.com. |

| Sickle Scaler • American Eagle Instruments, Missoula, Mont, offers the M23 Scaler, a universal sickle scaler designed with special bends and angulation. It is available in 5/16” stainless steel handle as well as the EagleLite 3/8” stainless steel and resin handles. (800) 551-5172; www.am-eagle.com. |

|

|

Loupe Frames • PeriOptix, Mission Viejo, Calif, introduces the new Hogies™ frames available for the 2.5x, 3x, and 3.5x Performance Series™ loupes. They are available in nine colors and feature a magnetic mounting system. They offer wrap-around side arms designed for comfort and stability without headstraps. (888) 360-0033;www.perioptix.com. |

| Instrument Line • PDT/Paradise Dental Technologies, Missoula, Mont, produces the Cruise line of instruments. They are solid resin with nonsilicone knurling pattern. The instruments are anatomically color-coded with a wide diameter. (800) 240-9895; www.pdtdental.com . |

|

|

Loupe Systems • Orascoptic-SDS, Middleton, Wis, offers HiRes™ and Dimensions-3® wide-field loupe systems. They have ergonomically customized working angles with high resolution across the operating field. They are available in either flip-up or through-the-lens and can be mounted on two titanium frame styles. (800) 369-3698; www.orascoptic.com. |

| Optical Loupes • SheerVision Inc, Rolling Hills Estates, Calif, offers optical loupes with a 4 inch field of view and an extended depth of field. They are lightweight with a flip-up design and the angle of declination can be adjusted. (877) 678-4274; www.sheervision.com. |  |

|

Ultrasonic Handpiece • DENTSPLY Professional, York, Pa, offers the Cavitron® Steri-Mate® handpiece with swivel. The ergonomic handpiece can be used with a variety of insert designs. It offers a 330° swivel feature at the juntion of the handpiece and the cable. (877) 794-8357; www.professional.dentsply.com. |

| Seating System • SurgiTel, Ann Arbor, Mich, introduces ErgoComfort™ Seating Systems, ergonomically designed stools. Adjustment mechanisms for height and tilt allow users to adjust to personal seating requirements. The backrest and the stool istelf can also be adjusted. The patented “Relax” and “Hydro” support arms swing side-to-side and forward and back. (800) 959-0153;www.surgitel.com. |  |

|

Ultrasonic scaler • Brasseler USA, Savannah, Ga, offers the Varios 350™ compact multifunction ultrasonic scaler. The Varios 350 measures 32 mm tall by 80 mm wide and 140 mm deep. The lightweight handpiece has an ergonomic, sculpted design. It is available in fiber optic lighting or nonfiber optic models. (800) 841-4522; www.brasselerusa.com. |

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. July 2004;2(7):10-12, 14, 16-17.