The Manifestations of Lyme Disease

This often misdiagnosed tick-borne disease produces oral signs and symptoms detectable in the dental setting.

This course was published in the February 2020 issue and expires February 2023. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Identify the route of transmission for Lyme disease.

- Discuss the three stages of Lyme disease and their signs and symptoms.

- Explain the role of oral health professionals in the detection and treatment of this tick-borne disease.

Lyme disease—which is spread via tick bite—is the most common vector-borne disease caused by Borrelia burgdorferi in the United States.1,2 In 2017, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported 42,743 confirmed cases of Lyme disease—an increase of 17% from 2016.2 While tick-borne infections are most common in the summer, due to increasingly warmer temperatures, ticks may still be active in the fall.3–7 The total number of Lyme disease cases is unknown because of the high prevalence of misdiagnoses. Lyme disease was first discovered in Lyme, Connecticut, in the mid-1970s when a large number of children presented with symptoms of juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Upon further examination, the arthritic symptoms were also accompanied by cardiac and neurologic findings, as well as the clinical presence of an expanding rash, erythema migrans. In the early 1980s, Wilhelm Burgdorfer, PhD, and colleagues isolated an unspecified bacterium from deer ticks. Their analysis revealed that the unspecified coiled spirochete was the etiological host of Lyme disease. Named after the founder, the spirochete is now known as Borrelia burgdorferi.3,8,9

TRANSMISSION

B. burgdorferi is spread through infected deer ticks and black-legged ticks.2,10 Ticks, which transfer the bacteria to humans via saliva through their bite, can transmit infection throughout their lives. Individuals living in suburban and rural areas are at highest risk of exposure. Ticks typically live in densely wooded areas, thick shrubs, high hedges, and small trees.11 They are unable to fly or jump, and often hold onto the tips of grass and shrubs with their lower legs, which is called “questing.” While ticks are questing, they climb onto a passing host and find an acceptable place to attach.11 Ticks require an area on the host that is well supplied with blood to feed, so they are usually found around the backs of the knees, armpits, groin, navel, and hair line.12 The infected tick needs to be attached to the host for approximately 24 hours to 48 hours to transfer the bacteria. Therefore, removing the tick at its earliest occurrence can reduce the risk of infection.10,13,14

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Oral health professionals should be familiar with the signs and symptoms of all stages of Lyme disease to better educate patients and support early detection of the disease. The stages of Lyme disease are: early localized, early disseminated, and late disseminated.6,15 Contingent on the stage of the illness, patients may present with various signs and symptoms that can affect multiple systems such as integumentary (exocrine), nervous, muscular, skeletal, and circulatory.10 Regardless of clinical presentation, the majority of patients with Lyme disease will see their clinical symptoms resolved if treated appropriately with antibiotics and antimicrobials. Misdiagnosis can lead to further progression of the disease and the need for prolonged treatment.16,17 The signs and symptoms associated with the different stages vary.

EARLY LOCALIZED STAGE

The early localized stage—which typically presents with the most common clinical manifestation of a “bull’s-eye” rash, or erythema migrans—occurs in approximately 80% of patients.6,11,13,15,18 Symptoms of erythema migrans usually appear at the site of a tick bite around 3 days to 30 days after exposure. The rash appears as a red macule or papule, erythematous, circular, and may have raised and warm borders. It can also appear as a target lesion and present with a vesicular and necrotic center (Figure 1).2,6,11,15 If untreated, erythema migrans increases in size by as much as 30 cm or more in diameter for days to weeks. Joint pain, fatigue, swollen glands, elevated temperature, stiff neck, conjunctivitis, difficulty concentrating, and sensitivity to light are common symptoms in the early localized stage.2,11,18 Oral symptoms may include transient periods of pain in the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) or masticatory muscle, as well as limitations in opening the mouth. Patients experiencing facial pain due to Lyme disease are frequently wrongly diagnosed with temporomandibular disorders (TMDs).15 Most patients with early Lyme disease recover when treated with appropriate therapy.16,17

EARLY DISSEMINATED STAGE

The onset of the early disseminated stage appears from weeks to a few months after infection and transpires once B. burgdorferi invade the bloodstream and settle in remote areas within the body.10,19,20 The most common manifestation in this stage is multiple sites of erythema migrans. These alternative skin lesions consist of an arrangement of ring-shaped erythematous lesions similar to but generally smaller than the initial lesion seen in the early localized stage. Other manifestations include facial nerve palsy, acute lymphocytic meningitis, and neck stiffness.19 Additional symptoms such as feeling light-headed, palpitations, labored breathing, chest pain, and fainting may be related to Lyme carditis (when B. burgdorferi enter the tissues of the heart). Myalgia, fatigue, burning and shooting pain that radiates on the skin, and migratory musculoskeletal pain in joints and bone are also symptoms of this stage. Although rare, inflammation of the iris and optic nerve damage have also been reported.6,10,21

LATE PERSISTENT STAGE

Disease progression in the late persistent stage occurs months to years after initial infection.19,20 The most common indicator is arthritis usually affecting large joints, specifically the knee. Although arthritis involvement can be migratory, typically five or fewer joints are affected.6 Other signs of Lyme arthritis may include inflammation of the tendons and TMJ pain.6 When the disease is untreated, damage to the nervous system occurs, causing Lyme neuroborreliosis, or a neurological manifestation of Lyme disease.3,4,15 The symptoms include inflammation of the brain, possible brain damage, and damage to the peripheral nerves. These signs often mimic other neurological diseases, which can lead to misdiagnosis.6,22 Studies show that exposure to the bacteria at any stage of Lyme disease can spread to the nervous system, joints, and other skin sites. However, the frequency of dissemination and the ability for the bacteria to persist varies, and early diagnosis is key to preventing further progression of disease.6,15,19,20,22

TREATMENT

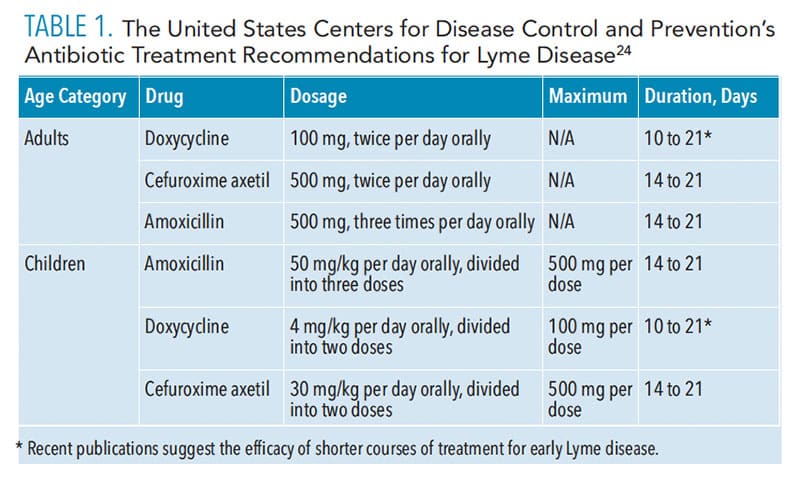

Oral health professionals should be familiar with Lyme disease treatments. In 2010, the Infectious Diseases Society of America published updated treatment recommendations for Lyme disease, which include antibiotics for all stages. However, the duration and route of treatment regimens differ, depending on the stage of disease.3,23 Different measures of prophylactic therapy are used depending on the stage of disease, and the complexity of treatment can vary depending on the involvement of the systems. Table 1 provides recommended dosages.24 While doxycycline is the first method of treatment, it is not the drug of choice for all patients, including pregnant women and children younger than 8 due to the risk of tooth discoloration; amoxicillin should be used instead.9,25 Recognizing and treating Lyme disease during pregnancy is crucial, as research indicates an association between untreated disease and pregnancy problems, including premature birth, stillbirth, and spontaneous abortion.3,9,10,25

PREVENTION

As Lyme disease is tick-borne, individuals must be vigilant to prevent getting bit by ticks. Personal protective measures such as wearing light-colored clothing (makes recognizing ticks easier), awareness of signs and symptoms, and using tick and insect repellents that contain N, N-Diethyl-meta-toluamide, or DEET, can reduce disease exposure. High bushes, trees, and grass should be kept trimmed, and large areas of leaves and wood piles should be removed. Avoiding heavily infested wooded areas and not sitting on the ground are also recommended.6,10,16

As studies suggest that the transmission of B. burgdorferi from infected ticks requires a prolonged duration of attachment, inspecting body, hair, and clothing after possible exposure is vital. Attached ticks should be removed immediately. Using the tip of a tweezer and avoiding any twisting motion, the tick should be removed by gently pulling it straight out.3,6,8,10,16 Ticks can fall off the host or clothes and can survive for 1 week to 2 weeks while searching for a new host. Consequently, when returning from areas of possible tick exposure, immediate inspection of the body and clothes should follow. Taking a hot shower and washing and drying clothes for 20 minutes on high heat to kill any ticks that may still be present are highly recommended.26 Once a tick is removed, putting it in alcohol and placing it in a sealed bag prior to disposal or flushing it down the toilet is advised.27 Control of Lyme disease progression depends the public’s willingness to follow protective guidelines, awareness of signs and symptoms, and the ability to seek medical treatment.5,6,10,11

ROLE OF ORAL HEALTH PROFESSIONALS IN DIAGNOSIS

Oral health professionals can recognize the signs and symptoms of Lyme disease and make referrals to primary care physicians. They are particularly well suited for this because the Lyme disease symptoms of head and neck pain may motivate patients to seek dental treatment. Clinicians need to be thorough when evaluating symptoms. A precise and comprehensive history of present illness, past medical history, and current social history must be acquired. The most common nondental orofacial pain condition associated with Lyme disease is a temporomandibular disorder (TMD), which may present as limitations in opening of the mouth, headache, facial pain, and joint clicking or popping.17 The causes of generalized muscle pain and/or arthritis should be investigated. TMD may be the manifestation of other underlying causes of systemic disease.28 While TMD involvement in Lyme disease has been reported in early studies, there is not substantial evidence confirming the correlation.15,26,28

Patients presenting with symptoms manifesting as Lyme neuroborreliosis may have facial pain due to nerve involvement, whereas patients with symptoms of Lyme arthritis experience pain in the joints.15 Burning mouth syndrome is sometimes present in patients with Lyme disease. While a direct cause-and-effect relationship has not been established, reports indicate that the presence of burning mouth syndrome in this patient population may be due to neurological manifestations of B. burgdorferi to the mandibular division on the trigeminal nerve.29 Ruling out other underlying diseases when treating patients with TMD symptoms is key to detecting Lyme disease. Investigating unclear, nonspecific TMDs, headaches, and facial pain is critical to preventing misdiagnosis.

SEROLOGICAL TESTING

The CDC recommends a two-phase serological test for Lyme disease.30 The first test administered is a sensitive enzyme immunoassay (EIA) or immunofluorescent assay (IFA), which looks for antibodies to B. burgdorferi. Specimens with negative results do not require further testing. Inconclusive or positive results are then analyzed by a western immunoblot assay for the presence of specific immunoglobulins: IgG and IgM.10,30,31 Recently the US Food and Drug Administration approved new guidelines for Lyme disease testing.32,33 These guidelines allow for an EIA to be used instead of the western immunoblot assay as the second test in the two-step process.

There are limitations to the serologic testing for Lyme disease. IgM antibodies may not become detectable until 2 weeks to 6 weeks after exposure, and their presence declines within 4 months to 6 months of the disease’s onset. They can also remain present in the bloodstream even after treatment, creating a false-positive result.3,10,30 These limitations make serologic testing contraindicated for those patients who present with erythema migrans. The rash most often presents before antibodies appear, which justifies the diagnosis of Lyme disease and antibiotic therapy once the rash is noted.10 Erythema migrans is frequently misdiagnosed, as it can be confused with eczema, insect bites, or ringworm. However, erythema migrans tends to abruptly increase in size, and patients should be monitored for 1 day to 3 days if a definitive diagnosis is not initially possible.6

CONCLUSION

Collaboration between oral health professionals, patients, and other health care providers is key to the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of Lyme disease. Education and awareness are key to prevention and management of Lyme disease, which is central to ensuring public health. As such, oral health professionals should be knowledgeable about the stages of Lyme disease and its signs and symptoms. Patients who may have Lyme disease should be advised to see their primary care physicians, who can make the necessary referrals to board-certified specialists in infectious disease. With an incidence that has risen dramatically over the past 10 years and increasingly warmer temperatures, which are favored by ticks, all health care professionals, including dental, need to be prepared to act quickly to assist patients who may be vulnerable to Lyme disease.5,10,11

REFERENCES

- Johnson L, Wilcox S, Mankoff J, Stricker RB. Severity of chronic Lyme disease compared to other chronic conditions: a quality of life survey. PeerJ. 2014;2:e322.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recent Surveillance Data. Lyme Disease. Available at: cdc.gov/lyme/data surveillance/recent-surveillance-data.html. Accessed January 16, 2020.

- Nichols C, Windemuth B. Lyme disease: from early localized disease to post-lyme disease syndrome. J Nurse Pract. 2013;9:362–367.

- Miraglia CM. A Review of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Guidelines for the Clinical Laboratory Diagnosis of Lyme Disease. J Chiropr Med. 2016;15:272–280.

- Bouchard C, Dibernardo A, Koffi J, Wood H, Leighton P, Lindsay L. Increased risk of tick-borne diseases with climate and environmental changes. Canada Commun Dis Rep. 2019;45:83–89.

- Gern L, Falco RC. Lyme disease. Rev Sci Tech L’oie. 2016;19:121–135

- Kugeler KJ, Farley GM, Forrester JD, Mead PS. Geographic distribution and expansion of human lyme disease, United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21:1455–1457.

- Borchers AT, Keen CL, Huntley AC, Gershwin ME. Lyme disease: A rigorous review of diagnostic criteria and treatment. J Autoimmun. 2015;57:82–115.

- Pöyhönen H, Nurmi M, Peltola V, Alaluusua S, Ruuskanen O, Lähdesmäki T. Dental staining after doxycycline use in children. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2017;72:2887–2890.

- Ziegler RM, Didas CM, Smith JS. Diagnosing and managing Lyme disease. J Am Acad Physician Assist. 2013;26:21–26.

- Heir GM, Fein LA. Lyme disease: considerations for dentistry. J Orofac Pain. 1996;10:74–86.

- Rahlenbeck S, Fingerle V, Doggett S. Prevention of tick-borne diseases: an overview. Br J Gen Pract. 2016;66:492–494.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It’s Open Season on Ticks! Available at: cdc.gov/features/hunting-season-ticks/index.html. Accessed January 16, 2020.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Lifecycle of Blacklegged Ticks. Available at: cdc.gov/lyme/transmission/blacklegged.html. Accessed January 16, 2020.

- Osiewicz M, Manfredini D, Biesiada G, et al. Differences between palpation and static/dynamic tests to diagnose painful temporomandibular disorders in patients with Lyme disease. Clin Oral Investig. 2019;23:4411–4416.

- Murray TS, Shapiro ED. Lyme disease. Clin Lab Med. 2010;30:311–328.

- Osiewicz M, Manfredini D, Biesiada G, et al. Prevalence of function-dependent temporomandibular joint and masticatory muscle pain, and predictors of temporomandibular disorders among patients with Lyme disease. J Clin Med. 2019;8:929.

- Walker BW. Responding to neurologic effects of Lyme disease. Nursing (Lond). 2008;38:20.

- Elbaum-Garfinkle S. Close to home: A history of Yale and Lyme disease. Yale J Biol Med. 2011;84:103–108.

- Bockenstedt LK, Wormser GP. Unraveling Lyme disease. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66:2313–2323.

- Steere AC, Coburn J, Glickstein L, Steere AC, Coburn J, Glickstein L. Review series: the emergence of Lyme disease. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1093–1101.

- Schwenkenbecher P, Pul R, Wurster U, et al. Common and uncommon neurological manifestations of neuroborreliosis leading to hospitalization. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17:1–10.

- Infectious Diseases Society of America. Available at: idsociety.org/globalassets/idsa/topics-of-interest/lyme/idsalymediseasefinalreport.pdf. Accessed January 16, 2020.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Treatment. Available at: cdc.gov/lyme/treatment/index.html. Accessed January 16, 2020.

- Wormser GP, Wormser RP, Strle F, Myers R, Cunha BA. How safe is doxycycline for young children or for pregnant or breastfeeding women? Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2019;93:238–242.

- Xie J, Washington N, Chandran R. An unexpected souvenir: Lyme disease presenting as TMJ Arthritis. Available at: pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/141/1_MeetingAbstract/693.full. Accessed January 16, 2020.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tick Removal and Testing. Available at cdc.gov/lyme/removal/index.html. Accessed January 16, 2020.

- Kumar A, Brennan MT. Differential diagnosis of orofacial pain and temporomandibular disorder. Dent Clin North Am. 2013;57:419–428.

- Young K, DeKlotz T, Reilly M. Burning mouth syndrome: a rare manifestation of lyme disease. Otolaryngol Neck Surg. 2010;143(2_Suppl):P159–P159.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System. Nationally Notifiable Infectious Diseases. Available at: cdc.gov/nndss/conditions/notifiable/2016. Accessed January 16, 2020.

- Arvikar SL, Steere AC. Diagnosis and treatment of Lyme arthritis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2015; 29: 269–280.

- United States Food and Drug Administration. FDA Clears New Indications for Existing Lyme Disease Tests That May Help Streamline Diagnoses. Available at: fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-clears-new-indications-existing-lyme-disease-tests-may-help-streamline-diagnoses. Accessed January 16, 2020.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated CDC Recommendation for Serologic Diagnosis of Lyme Disease. Available at: cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/68/wr/mm6832a4.htm?s_cid=mm6832a4_w. Accessed January 16, 2020.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. February 2020;18(2):40–43.