IDEABUG/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

IDEABUG/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

Caring for Children With Sensory Processing Disorders

Understanding these neurodevelopmental disorders will help oral health professionals provide safe and effective care.

This course was published in the February 2020 issue and expires February 2023. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Explain the prevalence of neurodevelopmental disorders in children, including sensory processing disorders, and the two categories of sensory processing disorders most recognizable by oral health professionals.

- Describe the unique and fluid nature of sensory processing disorders, and why adapting the dental environment to the patient’s specific needs can improve care.

- List techniques that can help prepare these patients for a successful dental visit and support optimal care while in the clinic.

The United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention1 reports that one in six children has one or more neurodevelopmental disorders, including autism spectrum disorder (ASD), attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, or an intellectual disability disorder. While not defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders as an independent disorder, sensory processing disorders are increasingly recognized by clinicians in individuals who have problems interacting with the world through their senses.2 Typical human behavior includes the ability to receive input from one or more senses (such as vision, touch, or hearing), identify them in the brain, and respond appropriately. An individual with a sensory processing disorder has difficulty receiving and responding to these sensory messages. As a result, interactions with the environment are not predictable.3

Among these patients, maintaining health (and oral health, in particular) can be complicated by sensory over-responsivity.4 As expected, the dental environment and professional care is often met with anxiety and behavioral problems, and parents/caregivers of children with ASD and sensory processing disorders report difficulty and poor compliance during dental visits, leading to more frequent cancellations. As a result, caries and periodontal diseases are frequent and age of onset tends to be earlier in this population. The use of medications to assist in treatment is common, but increasing understanding of nonpharmacological approaches may benefit these patients, as well.5

Research indicates that sensory processing disorders are present in 5% to 16% of typically developing children,6–8 and the majority of children with ASD have sensory processing disorders. The incidence of ASD is on the rise, with increased numbers of these children seen in dental offices.3 Less attention has been paid to typical children with sensory processing disorders, as they may be more difficult to identify.

Sensory-adapted dental environments based on individual needs have been identified as beneficial for pediatric patients and their parents/caregivers; studies evaluating the impact on perceived pain, anxiety, profound distress, and related magnitude of negative behaviors have shown positive outcomes in children with ASD and related sensory processing disorders.3,5,9,10 Additionally, protocols using visual supports and social stories to increase the child’s awareness of the dental process may calm fears, thereby increasing acceptance of care and, ultimately, improving oral health.

Along with individualized adaptations, parent/caregiver training is a key component of addressing sensory issues,11 but few resources are available that are specifically designed for parents/caregivers when bringing children with sensory processing disorders to the dentist. Understanding challenges and strategies to address these special needs may decrease stress for patients, parents/caregivers, and providers. These methods may also decrease the need for physical restraints and/or pharmacological management, shorten appointment times, and, ultimately, reduce associated costs. With the rise in the number of children with neurodevelopmental disorders, it is essential to enhance professionals’ self-efficacy in providing care. Unfortunately, within the dental field, specialized services and training to care for these populations have not grown in proportion to demand. The goal of this article is to help dental teams deepen their understanding of sensory processing disorders and their impact on oral health, and develop the skills to overcome the challenges associated with treating this patient population.

UNDERSTANDING SENSORY INTEGRATION

Sensory integration is the neurological process of organizing sensory inputs for function in daily life. The brain must take sensory input from our eight senses and send signals to the body in response to that input. These eight senses include the five most familiar: vision, auditory, tactile, taste, and smell. The other three include vestibular (our sense of movement and balance), proprioception (the sense of where our body is in space), and interoception (a sense of what is going on within our bodies, such as heart rate, hunger, and thirst). An inability to effectively respond to sensory inputs impacts daily activities. For example, a sensory processing disorder involves more than just discomfort with bright lights or loud sounds; rather, it causes inability to function in daily life.12

Sensory processing disorders may be related to problems with learning, motor development, or behavior. These might include coordination problems; poor attention span; problems with academic-related tasks (such as handwriting or cutting with scissors); unusually high or low activity levels; problems with self-care (such as tying shoes, dressing, or eating); low self-esteem; poor social interaction; and oversensitivity to touch, sights, or sounds.

SENSORY AVOIDERS VS SENSORY SEEKERS

Two categories of sensory processing disorders are most recognizable by oral health professionals. Sensory avoiders are individuals who overrespond to certain sensory inputs. In comparison, sensory seekers crave specific sensory inputs, such as vestibular (movement) or touch (see sidebar on page 36 for more information on caring for sensory-seeking patients). Because sensory seekers cannot seem to get enough sensory input, they are typically not as challenging to work with in the dental office. Children who are sensory avoiders are likely to respond to certain sensory input as though it is painful or irritating. This triggers their autonomic nervous system to respond with fight, flight, or freeze reactions. The negative responses may be extreme and include (but are not limited to) hitting, biting, closing the mouth and eyes, running away, crying, or yelling. These behaviors can make the dental visit extremely challenging or even impossible.

Many children are both sensory seekers and sensory avoiders. It is common for a child with sensory processing disorders to be a seeker of one sensation and avoider of another. In addition, no two children are alike, and sensory processing can vary from day to day or moment to moment. Considering the likelihood these patients will have difficulty with more than one input,13 dental teams are advised to consider and address each patient’s individual needs.

PRIOR TO TREATMENT

Effective communication with parents/caregivers is crucial when treating this patient population. Collecting information about the child’s sensory needs can help prevent challenging behaviors while in the dental chair. Questions to ask parents/caregivers include what the child is sensitive to, favorite (or disliked) flavors, and whether the patient is light sensitive. Dental teams might also ask if the patient is comfortable lying in a reclined position, and whether the overhead monitor should be on or off. The questioning might extend to the child’s self-care regimen and recent experiences with dental providers.

Parents/caregivers are the dental team’s ally, and working collectively will facilitate optimal care for children with sensory processing disorders. These individuals understand their child better than anyone else, so taking the time to listen and learn is time well spent.

Prior to the appointment, parents/caregivers need to prepare the child.14 A get-acquainted visit with the office and staff prior to coming for the actual appointment can be very helpful.15 Lacking this previsit, the child could be overwhelmed by the operatory environment. Considering it is easier to prevent sensory avoidance than correct it once it has occurred, dental teams should schedule sufficient time when caring for these patients, and allow them to ease into care at a slow pace.

Another way to effectively prepare children and their parents/caregivers is to read a book or social story together about going to the dentist.16 A social story can be easily designed by oral health professionals to help educate the family about the dental visit. A story that clearly explains and shows pictures of each step of the dental visit is best.17 The parent/caregiver should start reading the story with the child a week or more prior to the visit, so the child has time to reflect and ask questions. Information about designing a social story can be found at: carolgraysocialstories.com.

ENVIRONMENTAL CONSIDERATIONS

Visual Environment. Some children love bright, primary colors. However, bright colors and busy décor can be overwhelming, especially for children with sensory processing disorders. Warm tones and calming colors, such as light blue, tan, or gray, are best. Additionally, avoid bright lights, especially flashing the dental light into the child’s eyes. Teams may also wish to cover any blinking lights. Decluttering and organizing workspaces will also be helpful. Offering sunglasses for the patient is a simple method of preventing overstimulation from visual inputs.

Auditory Environment. Sporadic loud sounds, such as dental handpieces, can be overstimulating for a child with sensory processing disorders who is sensitive to sound. Using the operatory that is the furthest away from the source of the sound and providing noise-cancelling headphones may prove helpful. Background music is not always a good choice because it adds to the auditory input the child must process. Assuming the sound is acceptable to the child, a white noise machine may be a better choice. While most clinicians do not notice the humming or buzzing of fluorescent lights, patients with sensory processing disorders who are sensitive to sound will notice, and to them it may even be painful. Turn off fluorescent lights if possible, as well as extraneous equipment and screens. Another helpful technique is to place a towel under instruments so they do not clang against the tray as they are being retrieved and returned.

Tactile Adaptations. The dental environment can be overwhelming for a child who is hypersensitive to touch. When treating these patients, tell the child before touching will occur and avoid unexpected touching when possible. Briefly explain what is going to happen and be patient with the child. Always use a firm touch.18 Feather-like or very light touches tend to be bothersome for these patients. The extra weight of a lead apron or a weighted vest or weighted blanket may be calming. Children should also be allowed to bring their own blanket or toy that calms them.

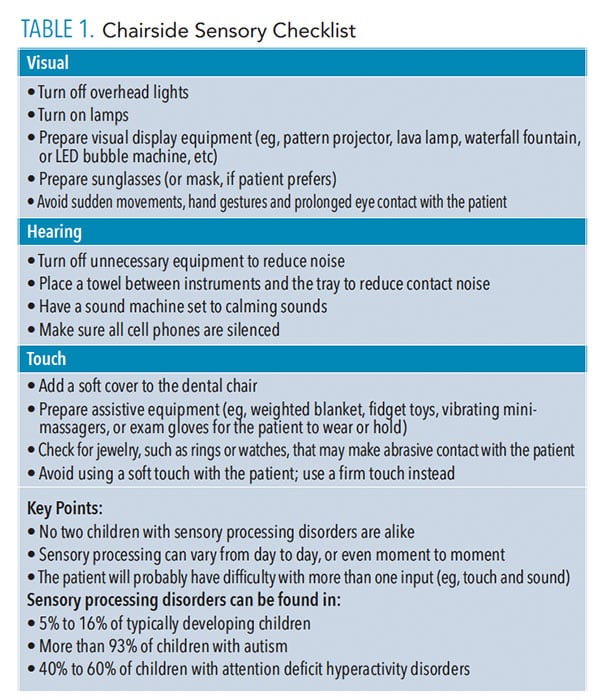

Smell and Taste Environment. Clinicians should avoid wearing products with scents. What others deem as pleasant smells may be unpleasant or overwhelming to a patient with a sensory processing disorder. Avoid gum or breath mints with strong scents. Do not give a sensory-avoiding child an overwhelming number of choices. Rather than offering five flavors of prophy paste or fluoride varnish, offer two choices that are based on prior consultation with the parent/caregiver. (Table 1 provides a chairside sensory checklist that can be implemented in practice.)

![Sensory checklist]() DURING TREATMENT

DURING TREATMENT

When approaching the patient, be warm and friendly but never overly enthusiastic. Speak in a quiet, calm voice. These patients should be told what is needed of them. For example, “Please open your mouth” will work better than “Can you open your mouth for me?” Children with sensory processing disorders may be slow to process and respond to language. Use fewer words and short phrases and give them time to process. Clinically, it can be helpful to provide an emotional check-in chart with words and facial expressions to allow the child to express how he or she is feeling. Check in often to make sure the patient is OK. A visual picture schedule—laminated drawings depicting each step in the procedure—will aid the child when transitioning between steps and will help build independence.19,20 The pictures could be attached to a ring the patient can hold and flip through as the clinician and child move through the appointment together, or the pictures could be larger and mounted to a clipboard or wall.

One of the most common challenges when treating children with sensory processing disorders is they do not want to lay back in the chair (or dental table commonly used in pediatric dental offices). Parents or caregivers can help by introducing the child to a reclining chair at home. The clinician might need to work on this over several appointments. In the meantime, the patient should be allowed to sit as upright as possible. When using dental tables, a possible solution might be using a foam wedge or beanbag for the patient to lean against.

CONCLUSION

Many children with sensory processing disorders have difficulty participating in routine dental care. Dental experiences that are perceived as unpleasant or stressful will likely stick with the child into adulthood, and may also negatively impact the attitudes of parents/caregivers. The result could lead to poor oral health for these patients. In light of this, and given the likelihood of encountering patients with sensory processing disorders, dental teams are encouraged to seek training in treating this population. Being willing to listen to parents/caregivers, as well the child, and trying easy environmental modifications will help clinicians provide a positive experience.10,19 Ultimately, these interventions have the potential to promote a lifetime of good oral health for these at-risk patients and families.

ADAPTING THE ENVIRONMENT FOR SENSORY SEEKERS

Sensory-seeking children have a difficult time sitting still and constantly seek out stimulation. Parents/caregivers of sensory seekers should be advised to build in extra time before their child’s appointment to allow him or her to release extra energy. For example, taking him or her to the playground, bike riding, jumping on a trampoline, or even running around the building before entering can help the child be better prepared for the appointment.

Visual. May prefer visual stimulation, such as bright lights, changing light patterns, or projected scenes/movies to watch during the appointment.

Auditory. May enjoy music with changes in volume, instrument/sounds with pitch or beat frequency, and audio books with kid-friendly stories.

Touch. Provide textured mat/disc/blankets to sit on, apply weighted blankets/vests/pillows/objects during appointment time, offer fidget spinners or other toys to keep seekers’ hands busy, or give sensory seekers devices that vibrate.

Taste. Give sensory seekers a choice of flavors. If possible, allow them to pick more than one, and switch flavors during procedures.

Smell. Use products with stronger smells, good or bad.

REFERENCES

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Facts about developmental disabilities. Available at: cdc.gov/ncbddd/developmentaldisabilities/facts.html. Accessed January 3, 2020.

- Dionne-Dostie, E, Paquette N, Lassonde M, Gallagher A. Multisensory integration and child neurodevelopment. Brain Sci. 2015;5:32–57.

- Kuhaneck HM, Chisholm EC. Improving dental visits for individuals with autism spectrum disorders through an understanding of sensory processing. Spec Care Dentist. 2012;32:229–233.

- Stein LI, Lane CI, Williams ME, Dawson ME, Polido JC, Cermak SA. Physiological and behavioral stress and anxiety in children with autism spectrum disorders during routine oral care. Biomed Res Int. 2014:694876.

- Shapiro M, Melmed RN, Sgan-Cohen, HD, Parush S. Effect of sensory adaptation on anxiety of children with developmental disabilities: a new approach. Pediatr Dent. 2009;31:222–228.

- Ben-Sasson A, Hen L, Fluss R, Cermak SA, Engel-Yeger, B, Gal E. A meta-analysis of sensory modulation symptoms in individuals with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2009;39:1–11.

- Ahn RR, Miller LJ, Milberger S, McIntosh DN. Prevalence of parents’ perceptions of sensory processing disorders among kindergarten children. Am J Occup Ther. 2004;58:287–293.

- Tomchek SD, Dunn W. Sensory processing in children with and without autism: a comparative study using the short sensory profile. Am J Occup Ther. 2007;61:190–200.

- Bodison SC, Parham, LD. Specific sensory techniques and sensory environmental modifications for children and youth with sensory integration difficulties: a systematic review. Am J Occup Ther. 2018;72:7201190040p1-7201190040p11.

- Cermak SA, Stein Duker LI, Williams ME, Dawson ME, Lane CJ, Polido JC. Sensory adapted dental environments to enhance oral care for children with autism spectrum disorders: a randomized controlled pilot study. J Autism Dev Disord. 2015;45:2876–2888.

- Reynolds S, Glennon T, Ausderau K, et al. Using a multifaceted approach to working with children who have differences in sensory processing and integration. Am J Occup Ther. 2017;71:7102360010p1–7102360010p10.

- Isbell C, Isbell RT. Sensory Integration: A Guide for Preschool Teachers. Gryphon House; Beltsville, Maryland: 2008.

- Miller LJ, Fuller, DA, Roetenberg J. Sensational Kids: Hope and Help for Children With Sensory Processing Disorders (SPD). Perigree Book; New York: 2014.

- Bondioli M, Pelagatti S, Buzzi MC, Senette C. ICT to aid dental care of children with autism. ASSETS. 2017;321–322.

- Pathmashri VP, Santhosh Kumar MP. Dental management of children with autism spectrum disorders. Drug Intervention Today. 2018;10(7):1190–1194.

- Anderson K, Self T, Carlson B. Interprofessional collaboration of dental hygiene and communication sciences and disorders students to meet oral health needs of children with autism. J Allied Health. 2017;46:E97–E101.

- Gray C. What is a Social Story? Available at: carolgraysocialstories. com/social-stories/what-is-it/. Accessed January 3, 2020.

- Delli K, Reichart PA, Bornstein MM, Livas C. Management of children with autism spectrum disorder in the dental setting: concerns, behavioral approaches, and recommendations. Med Oral Patol Cir Bucal. 2013;1:18.

- Elmore JL, Bruhn AM, Bobzien JL. Interventions for the reduction of dental anxiety and corresponding behavioral deficits in children with autism spectrum disorder. J Dent Hyg. 2016;90: 111–120.

- Cagetti M, Mastroberardino S, Campus G, et al. Dental care protocol based on visual supports for children with autism spectrum disorders. Medicina Oral Patologia Oral Y Cirugia Bucal. 2015;20:E598–E604.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. February 2020;18(2):34–37,39.