Managing Orofacial Pain

Oral health professionals should be prepared to address chronic idiopathic or dysfunctional orofacial pain conditions.

This course was published in the January 2018 issue and expires January 2021. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Define orofacial pain.

- Identify the initiating or aggravating factors of orofacial pain.

- Discuss the various causes, symptoms, and treatments for chronic idiopathic or dysfunctional orofacial conditions.

Orofacial pain can have a huge socioeconomic burden and psychosocial impact. It manifests as reduced quality of life, depression, and disrupted relationships; it also impacts work capacity. Economic burden arises from the pharmacological management of pain, cost of health insurance, and loss of employment. Lack of up-to-date knowledge among clinicians regarding the diagnosis and management of orofacial pain conditions can lead to misdiagnosis.1–3 Orofacial pain can be classified as acute or chronic pain, based on the duration of onset. This article will focus on a sampling of the chronic causes of orofacial pain; more specifically, chronic idiopathic or dysfunctional orofacial pain conditions.

The Australian Pain Management Association defines chronic orofacial pain as that which appears to originate from the head and neck region for more than 3 months. Chronic orofacial pain is a diagnosis of exclusion after considering more common possible causes. It can last for months to years, causing psychological morbidity and impacting quality of life.4,5 Chronic pain can be associated with idiopathic disorders, with specific etiology, and may accompany many diseases or disorders. Prevalence of chronic pain in adults is estimated at 12% to 30%, and is considered an epidemic.6–9 Chronic orofacial pain conditions are broadly classified as dysfunctional or idiopathic orofacial pain, neurovascular and tension type, and neuralgias;10,11 the latter two classifications will not be covered in this discussion. Other classification systems may include different categories, such as acute vs chronic, or arthrogenic vs myogenic. This article provides readers with the basic knowledge of etiology, nature of the pain periodicity, initiating or aggravating factors, and management of chronic idiopathic or dysfunctional orofacial pain conditions.

These conditions are a form of chronic pain that cannot be placed in the neurovascular and tension type, or neuralgias classification categories. Patients may present with nonspecific persistent pain, which may be due to a surgical intervention, or a dysfunction that cannot be attributed to a specific cause.

PERSISTENT IDIOPATHIC FACIAL PAIN

Etiology: According to the International Headache Society (IHS), persistent idiopathic facial pain (PIFP) does not have characteristics of any neuralgias and does not fulfill any other diagnosis. It may be due to insignificant trauma or minor surgery to the face, teeth, or gingiva. The pain may persist in spite of removal of the noxious stimuli and healing of the tissues post-surgically.12

Clinical Features: PIFP can have varying presentations, but recurs daily and persists for more than 2 hours to 3 hours, and for more than 3 months. Pain is often described as dull, aching, and nagging, or intermittent sharp pain without neurological deficits. It is difficult to localize and is associated with psychological disorders.12,13

Diagnosis: This is a diagnosis of exclusion, based on history, clinical examination, radiographs, and adjunctive testing.12,13Diagnostic criteria for PIFP have been described by IHS classification:12 A. Facial and/or oral pain fulfilling criteria B and C; B. Recurring daily for more than 2 hours per day for more than 3 months; C. Pain is poorly localized, and does not follow the distribution of a peripheral nerve; and it has dull, aching, or nagging quality; D. Clinical neurological examination is normal; E. A dental cause has been excluded by appropriate investigations; and F. Not better accounted for by another International Classification of Headache Disorders-3 (ICHD-3) diagnosis.

Treatment: Topical anesthetics and/or anticonvulsants are the first line of treatment, followed by antidepressants, analgesics, and anxiolytics.13

TEMPOROMANDIBULAR JOINT DISORDERS

Temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorders are musculoskeletal conditions that involve the TMJ, jaw muscles, and associated structures. The prevalence of masticatory muscle pain is 13%, disc derangement disorder prevalence is up to 16%, and TMJ pain disorders have a reported prevalence of up to 9%. These disorders are encountered twice as often in women than in men.6,14

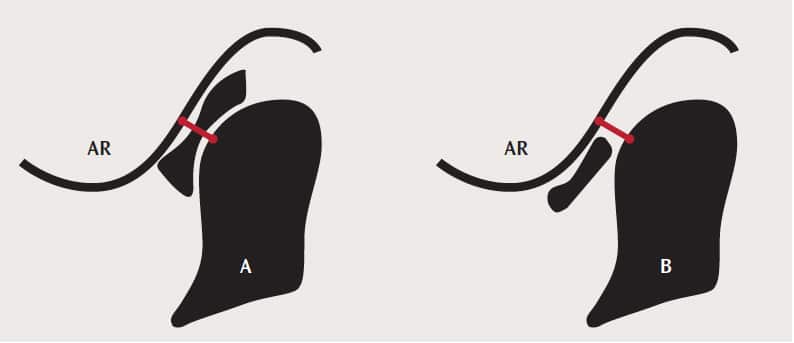

Disc displacement with reduction is a common noninflammatory condition of the TMJ. It is characterized by the abnormal alignment between the disc and condyle (Figure 1). The most common direction for displacement of the disc is anterior or antero-medially.6,15

Etiology: The causes of disc displacement are mainly elongated or torn ligaments (which attach the disc to condyle), and lubrication impairment in the joint space.6 The disc may be displaced due to direct or indirect trauma, daytime parafunction, or nocturnal bruxism.

Clinical Features: The movement of the disc between the condylar head and the temporal fossa may cause clicking, popping, or snapping sounds on opening and closing the mouth. The joint noises may be accompanied by pain or discomfort associated with jaw movements.14,16

Diagnosis: A diagnosis is confirmed with a positive history of joint noises, such as clicking, popping, or snapping, for the past 30 days. In addition to the examination, the clinician must confirm at least one of the following:15 clicking, popping, or snapping noise detected during opening and closing, with palpation during at least one of the three repetitions of the jaw opening/closing or clicking; popping, or snapping noise detected during opening and closing, with palpation during at least one of the three repetitions of the jaw opening and closing; and clicking, popping, or snapping noises detected, with palpation during at least one of the three repetitions of left lateral, right lateral , or protrusion movements.

Diagnosis can be confirmed with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the TMJ that shows:15 posterior band of the disc is located anterior to the 11:30 position and the condyle is not seated under the intermediate zone of the disc in maximum intercuspal position (Figure 1), and the intermediate zone of the disc is located between the condylar head and articular eminence on maximum opening.

Treatment: Disc displacement with reduction does not require treatment if the patient can open his or her mouth without discomfort. Explanation, reassurance, patient education, and self-care are the first line of treatment. Self-care includes limiting excessive jaw movements, heat massage, and using relaxation techniques. Occlusal stabilization appliances prevent bruxism. Physiotherapy, acupuncture, and behavioral techniques are alternative methods of treatment. Along with conservative treatment, analgesics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and muscle relaxants are also prescribed if the patient is symptomatic.17

Disc displacement without reduction is characterized by the disc being in an anterior position relative to the condyle in the closed-mouth position, and the disc does not reduce with the opening of the mouth.6

Etiology: The causes of disc displacement without reduction are similar to disc displacement with reduction, and include direct or indirect trauma.6

Clinical Features: Disc displacement without reduction is characterized by limited mandibular mouth opening and deflection on opening on the affected side, and limited lateral movements to the contralateral side. There may be pain on opening, with or without capsulitis.15

Diagnosis: A diagnosis can be confirmed by limited mouth opening and the patient being positive for:15 jaw lock or catch, so the mouth will not open all the way; limitation in jaw opening severe enough to interfere with the ability to eat; the maximum assisted mouth opening should be less than 40 mm.

Diagnosis can be confirmed with an MRI of the TMJ that shows: the posterior band of the disc is located anterior to the 11:30 position, and the intermediate zone of the disc is located anterior to the condylar head in the maximum intercuspal position or on full opening, the intermediate zone of the disc is located anterior to the condylar head.

Treatment: Management should include patient reassurance, education, and analgesics; in select cases, occlusal stabilization appliance and passive physiotherapy exercises may be used. Arthrocentesis or open surgical procedures may be needed if patients do not respond to conservative methods. In addition, NSAIDs may be prescribed when the patient presents with associated capsulitis.18

OSTEOARTHRITIS

Also known as osteoarthrosis or degenerative joint disease (DJD), osteoarthritis is a degenerative condition of the joint characterized by deterioration and abrasion of articular tissue, and concomitant remodeling of the underlying subchondral bone due to overloading of the remodeling mechanism.18

Etiology: Etiopathogenesis of DJD is multifactorial and complex. Osteoarthritis is usually seen in older adults, but is not uncommon in children. History of fracture, microtrauma, or repetitive adverse loading may lead to osteoarthritis. Disturbances of joints, such as internal derangement and prolonged myofascial pain, and associated systemic conditions, such as congenital and developmental abnormalities, increase susceptibility.18–20

Clinical Features: Patients may experience spontaneous pain at rest or with function associated with joint noises, such as crunching or grinding, during movement. In addition, DJD may result in malocclusion (eg., anterior open bite), when bilateral joints are involved, and contralateral posterior open bite when present unilaterally.6

Diagnosis: Taking a complete patient history, along with a clinical examination supported by radiographic evidence, will confirm an initial diagnosis of osteoarthritis.15 The diagnosis is confirmed by: the presence of joint pain; presence of joint noise in the last 30 days (crunching, grinding, or grating); and crepitus detected with palpation during unassisted maximum opening and lateral movements. Diagnosis must be confirmed via cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) of the TMJ, which will show at least one of the following: subchondral cyst (Ely’s cyst), erosion, generalized sclerosis, or osteophyte. Note: In DJD cases, CBCT has better sensitivity than MRI.20

Treatment: Management and treatment are focused on reducing pain and decreasing the inflammation in the joint. Patient education is a primary focus. Self-care, physiotherapy, acupuncture and topical ointments are among the nonpharmacologic forms of treatment.20

Occlusal stabilization appliances are used for joint stabilization, and to reduce muscle pain, bruxism, and joint loading.19–21 A combination of occlusal stabilization appliance and pharmacotherapy enhances patient comfort and contributes to better treatment outcomes. For mild to moderate inflammatory changes in DJD, NSAIDs are reported to be an effective first-line treatment. Topical ointments, such as 10% diclofenac sodium, or other compounded medications can also be used. When taken over time, supplements, such as glucosamine sulphate, have shown better efficacy than ibuprofen in patients being treated for degenerative TMJ disease.22–26 Severe TMJ osteoarthritis can be treated with intra-articular injections of local anesthetics or corticosteroids and arthrocentesis.27,28 Surgical interventions are only considered when conservative treatment has failed.

MYOFASCIAL PAIN

Myofascial discomfort is pain of muscular origin, including pain associated with localized areas of tenderness to palpation in muscles.29 It involves discomfort or pain in the muscles that control jaw function. It is referred from, or emanates around, active myofascial trigger points.

Etiology: The etiology of localized myalgia and myofascial pain is multifactorial. Factors contributing to myofascial pain include physical sources (eg, malocclusion, trauma, jaw alignment or poor posture), psychosocial aspects (eg, anxiety, stress, and interpersonal or oral habits), inflammatory or systemic conditions (eg, polymyalgia rheumatica, polymyositis, dermatomyositis, lupus erythematosus or fibromyalgia), or idiopathic sources (eg, ischemia of the muscle).30,31

Clinical Features: Myofascial discomfort presents as a dull, aching pain that is generally localized to the area of palpation. The pain increases with movement. Taut bands of muscles (trigger points) may be present in the muscles. These hyperirritable bands are easily palpable. They are mainly limited to the temporalis and masseter muscles. There may be limitation of mandibular movements, and the pain may radiate beyond the boundaries of the muscle being palpated.29–31 The patient may describe transient facial numbness, hyperalgesia and allodynia.6,32

Diagnosis: A diagnosis may be confirmed when the history is positive of, or for,15 pain in the jaw, temple, in front of, or in, the ear (when ear infections are ruled out) in the last 30 days. A confirmation of pain in the area of the temporalis and masseter muscles can be achieved by examining for: pain changes with jaw movement, jaw function, or parafunction; familiar muscle pain with palpation and maximum assisted or unassisted opening; pain with muscle palpation beyond the boundary of the muscle

Treatment: The primary goals of therapy are pain management and restoration of normal function and movement. Treatment includes reassurance, patient education, self-care, physiotherapy, intraoral appliance therapy, pharmacotherapy, and behavioral/relaxation techniques.29 Moist heat and physiotherapy (in the form of passive exercises) are advised. Occlusal stabilization appliances or splints are frequently recommended. Pharmacotherapy includes muscle relaxants, NSAIDs, tricyclic antidepressants, local anesthetics, and compounded topical medications, as well as botulinum toxin and trigger point injections.30–37

BURNING MOUTH SYNDROME

Burning mouth syndrome (BMS) is described as a burning sensation in the oral mucosa occurring in the absence of clinically apparent mucosal abnormalities or laboratory findings, and is often perceived as pain. Prevalence rates in the general population are reported at 0.7% to 15%. Women are affected more commonly than men.6,38,39

Etiology: The pathophysiology of BMS is poorly understood. Although dental procedures or recent use of medications (eg, antibiotics) have been implicated, a neuropathic origin may be more likely. Onset of symptoms is spontaneous, but may be followed by an upper respiratory tract infection. BMS is classified as primary (etiology unknown) or secondary (etiology known).39,40

Clinical Features: Affecting the dorsal and lateral surface of the tongue, anterior hard palate, and buccal mucosa, BMS presents as a persistent burning sensation without any visible mucosal changes. The pain varies from mild to severe. Patients may complain of xerostomia and altered taste sensation (eg, a metallic taste). Eating, chewing gum, or sucking on candies can reduce the symptoms.40,41

Diagnosis: A diagnosis is based on complete history and exclusion of local irritating factors or systemic diseases. The common underlying causes could be candidiasis, hyposalivation, autoimmune mucosal lesions, allergies, vitamin deficiencies. or drug-induced mucositis. Diagnosis can be confirmed with cytological smears, patch testing, blood testing, and by measuring salivary flow.40–42

Treatment: This condition is difficult to treat; commonly, the patient will have consulted multiple practitioners without any resolution. Nonpharmacological treatments, such as cognitive behavior therapy and biofeedback, have shown positive results.42Pharmacological treatment involves topical medications (eg, clonazepam, capsaicin, or oral lidocaine) and systemic drugs (eg, clonazepam or tricyclic antidepressants). Complementary and alternative medications have also proven to be effective.42

With the increasing prevalence of patients presenting with orofacial pain, oral health professionals should be well versed in the wide spectrum of orofacial pain disorders, and the various causes, symptoms, and treatments. When indicated, it is equally important for clinicians to be able to refer these patients to an orofacial pain specialist for further management.

REFERENCES

- International Association for the Study of Pain Available at: iasp-pain.org. Accessed December 12, 2017.

- Cousins MJ, Gallagher RM. Fast Facts: Chronic and Cancer Pain. 2012

- American Board of Orofacial Pain. Available at: abop.net. Accessed December 12, 2017.

- Sessle B. Orofacial Pain: Recent Advances in Assessment, Management and Understanding of Mechanisms. Available at: http://ebooks.iasp-pain.org/orofacial_pain. Accessed December 12, 2017.

- Berman LH, Hartwell GR. Diagnosis. In: Cohen S, Hargreaves K, eds. Pathways of the pulp. 9th ed. St. Louis, Mo: Mosby Inc; 2006:

- de Leeuw R, Klasser GD. Orofacial Pain Guidelines for Assessment, Diagnosis and Management. 5th ed. Illinios: Quintessence Publishing Co; 2013.

- de Moraes Vieira EB, Garcia JB, da Silva AA, Mualem Araújo RL, Jansen RC. Prevalence, characteristics and factors associated with chronic pain with and without neuropathic characteristics in São Luís, Brazil. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012;44:239–251.

- 8 Schopflocher D, Taenzer P, Jovey R. The prevalence of chronic pain in Canada. Pain Res Manag. 2011;16:445–450.

- Moulin DE, Clark AJ, Speechley M, Morley-Forster PK. Chronic pain in Canada-prevelance, treatment, impact and the role of opioid analgesia. Pain Res Manag. 2002;7:179–184.

- Khawaja N, Yilmaz Z, Renton T. Case studies illustrating the management of trigeminal neuropathic pain using topical 5% lidocaine plasters. Br J Pain. 2013;7:107–113.

- Alberts I. Idiopathic orofacial pain: a review. The Internet Journal of Pain, Symptom Control and Palliative Care. 2008;6:1–7.

- International Headache Society classification ICHD-3 Beta. Available at: ihs-headache.org. Accessed December 12, 2017.

- Klasser GD, Management of persistent idiopathic facial pain. J Can Dent Assoc 2013;79:d71.

- National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research. Available at: nidcr.nih.gov. Accessed December 12, 2017.

- Schiffman E, Ohrbach R, Truelove E, et al. Diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders (DC/TMD) for clinical and research applications: recommendations of the International RDC/TMD Consortium Network and Orofacial Pain Special Interest Group. J Oral Facial Pain Headache. 2014;28:6–27.

- Young A. Internal derangements of the temporomandibular joint: a review of the anatomy, diagnosis, and management. J Indian Prosthodont Soc. 2015;15: 2–7.

- Scrivani SJ, Keith DA, Kaban LB. Temporomandibular disorders. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2693–2705.

- Miernik M, Więckiewicz W. The basic conservative treatment of temporomandibular joint anterior disc displacement without reduction-review. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2015;24:731–735.

- Kalladka M, Quek S, Heir G, Eliav E, Mupparapu M, Viswanath A. Temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis: diagnosis and long-term conservative management: a topic review. J Indian Prosthodont Soc. 2014;14:6–15.

- Tanaka E, Detamore MS, Mercuri LG. Degenerative disorders of the temporomandibular joint: etiology, diagnosis, and treatment. J Dent Res. 2008;87:296–307.

- Meng JH, Zhang WL, Liu DG, Zhao YP, Ma XC. Diagnostic evaluation of the temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis using cone beam computed tomography compared with conventional radiographic technology. Beijing Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2007;39:26–29.

- Inchingolo F, Tatullo M, Marrelli M, et al. Combined occlusal and pharmacological therapy in the treatment of temporo-mandibular disorders. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2011;15:1296–1300.

- McAlindon TE, LaValley MP, Gulin JP, Felson DT. Glucosamine and chondroitin for treatment of osteoarthritis: a systematic quality assessment and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2000;283:1469–1475.

- Li C, Jia Y, Zhang Q, SHI Z, Chen H. Glucosamine hydrochloride combined with hyaluronate for temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis: a primary report of randomized controlled trial. Hua Xi Kou Qiang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2011;29:632–635,639.

- Thie NM, Prasad NG, Major PW. Evaluation of glucosamine sulfate compared to ibuprofen for the treatment of temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis: a randomized double blind controlled 3 month clinical trial. J Rheumatol. 2001;28:1347–1355.

- Haghighat A, Behnia A, Kaviani N, Khorami B. Evaluation of Glucosamine sulfate and Ibuprofen effects in patients with temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis symptom. J Res Pharm Pract. 2013;2:34–39.

- Iturriaga V, Bornhardt T, Manterola C, Brebi P. Effect of hyaluronic acid on the regulation of inflammatory mediators in osteoarthritis of the temporomandibular joint: a systematic review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2017;46:590–595.

- Laudenbach J, Stoopler E. Temporomandibular Disorders: A Guide For The Primary Care Physician. The Internet Journal of Family Practice. 2002;2:1–7.

- Greenberg MS, Glick M. Burket’s Oral Medicine Diagnosis and Treatment. 10 ed. Hamilton, Ontario: BC Decker Inc; 2003:284.

- Romero-Reyes M, Uyanik JM. Orofacial pain management: current perspectives. J Pain Res. 2014;7:99–115.

- Greene CS. The etiology of temporomandibular disorders: implications for treatment. J Orofac Pain. 2001;15:93–105.

- Mense S. The pathogenesis of muscle pain. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2003;7:419–425.

- Graff-Radford SB. Myofascial pain: diagnosis and management. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2004;8463–467.

- Okeson JP. Bell’s Orofacial Pains: The Clinical Management of Orofacial Pain. 6th ed. Carol Stream, IL: Quintessence Publishing Co Inc: 2005.

- Okeson JP. The classification of orofacial pains. Oral Maxillofacial Surg Clin N Am. 2008;20:133–144.

- McNeill C. Temporomandibular Disorders: Guidelines for Classification, Assessment, and Management.2nd ed. Chicago, IL: Quintessence Publishing Co Inc;1993.

- Wright EF, North SL. Management and treatment of temporomandibular disorders: a clinical perspective. J Man Manip Ther. 2009;17:247–254.

- Bergdahl M, Bergdahl J. Burning mouth syndrome: prevalence and associated factors. J Oral Pathol Med. 1999;28:350–354.

- Klasser GD, Fischer DJ, Epstein JB. Burning mouth syndrome: recognition, understanding, and management. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2008;20:255–271.

- Sunil A, Mukunda A, Gonsalves MN, Basheer AB, Deepthi K. An overview of burning mouth syndrome. Indian J Clin Prac. 2012;23:145–152.

- Gurushka M. Clinical features of burning mouth syndrome. Oral. Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol.1987;63:30–36.

- Nasri-Heir C, Zagury JG, Thomas D, Ananthan S Burning mouth syndrome: current concepts. J Indian Prosthodont Soc. 2015;15:300–307.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. January 2018;16(01):44-47.