Manage Medications Safely

Patient safety is supported by proper prescription labeling, distribution, storage, and disposal of medications in the dental setting.

This course was published in the May 2014 issue and expires May 31, 2017. The author has no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Identify best practices for issuing prescriptions.

- Discuss proper protocol for dispensing and labeling medications.

- Explain how to properly identify medications to ensure the correct one is used.

- List the steps for the safe maintenance of a drug inventory.

- Detail strategies for safely storing and disposing of medications.

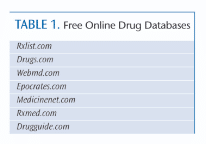

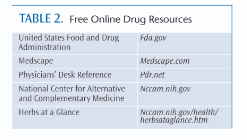

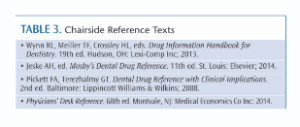

Managing medications effectively is a critical component of the dental office safety plan. Every attempt must be made to maintain accurate records regarding a patient’s medication use. Drug information systems should be utilized to assist with interpreting indications, contraindications, and adverse events, and to check compatibility prior to prescribing new medications. Subscription services that provide information on preventing drug interactions and complications are available, as well as free online databases (Table 1 and Table 2) and reference texts (Table 3)

All members of the dental team must make a conscientious effort to prevent medication errors during the provision of care. A medication error is defined as “a failure in the treatment process that leads to, or has the potential to lead to, harm to the patient.”1,2 These errors include: prescribing faults (irrational, inappropriate, and ineffective prescribing, under-prescribing, overprescribing); prescription errors (writing the prescription); dispensing the formulation (wrong drug, formulation, or labeling); administering or taking the medicine (wrong dose, route, frequency, or duration); and monitoring therapy (failing to alter therapy when required, erroneous alteration).1,2

ISSUING PRESCRIPTIONS

The entire dental staff is responsible for ensuring the safekeeping of prescription pads. They should never be kept in patient treatment areas or left unattended.3 Dentists should not preprint their United States Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) numbers on their prescription pads to reduce the likelihood that a stolen prescription pad could be used to obtain controlled substances. Stolen prescription pads should be reported to the appropriate authorities and, where specified, to the state dental board.

Today, many dental offices generate prescriptions using computer software programs, which can be programmed to retrieve templates for frequently prescribed medications. Patient information and date of issuance are entered prior to printing.

Each prescription should be checked for accuracy prior to giving it to a patient. Often, modifications are required due to the patient’s age or because of an existing medical condition. Dentists are encouraged to write notes to the pharmacist about any modifications made to standard dosing regimens directly on the prescription. If a computer-generated prescription is used, dosage adjustments and notes to the pharmacist should be added prior to printing the prescription. Printouts should be rechecked, as printer artifacts may resemble decimal points, which could inadvertently cause misinterpretation of medication dosages.

Use of electronic prescriptions, known as e-prescribing, significantly reduces medication errors associated with illegible handwriting, limits the wait time for patients to receive medications, and decreases the risk of prescription tampering.4 In the US, the vast majority of chain, community-based, and independent pharmacies access electronic prescriptions through Surescripts—a national networking system that allows for secure electronic communication between physicians, hospitals, pharmacies, and third-party payers.4,5 Allscripts is another clinical networking system that connects clinical and financial data across multiple settings.6 In medicine, most e-prescribing is conducted through electronic health records; however, transitioning to this mechanism has been slower in dentistry.

Prescribing drugs for uses outside the scope of dental practice is not permitted, and may result in disciplinary action by the state licensing board. Pharmacists play a critical role in screening for and reporting inappropriate prescribing behaviors. Staff members must monitor, address, and report inappropriate prescribing behaviors, as well. When a prescribed drug seems outside the normal scope of dental practice—such as the use of an antidepressant to manage chronic facial pain—the dentist is encouraged to document the indication for use directly on the prescription. Including the indication reduces the need for pharmacist intervention and follow-up.7

Prescribing drugs for uses outside the scope of dental practice is not permitted, and may result in disciplinary action by the state licensing board. Pharmacists play a critical role in screening for and reporting inappropriate prescribing behaviors. Staff members must monitor, address, and report inappropriate prescribing behaviors, as well. When a prescribed drug seems outside the normal scope of dental practice—such as the use of an antidepressant to manage chronic facial pain—the dentist is encouraged to document the indication for use directly on the prescription. Including the indication reduces the need for pharmacist intervention and follow-up.7

If two individuals within the same household require the same drug (eg, both use the same home fluoride), each person should be given his/her own prescription for the medication. Prescriptions may only be issued to patients of record and for the treatment of a documented oral care need. Prescriptions may not be generated for family members, staff members, or friends of the dentist unless they are patients of record and have a documented oral care need.3 Dentists are not permitted to self-prescribe medications.3

DISPENSING AND LABELING

It is commonplace for dental offices to dispense certain prescription drugs directly to patients from the office, most notably home fluorides and 0.12% chlorhexidine gluconate mouthrinses. Occasionally, dentists also may dispense antibiotics and prescription pain relievers. Dental professionals are reminded that, as with all prescription drugs, dispensed medications must be labeled appropriately in accordance with the law.

Labels must contain the same information found on prescription drug containers dispensed from the pharmacy. This information includes, but is not limited to: dentist’s name, office address, and phone number; patient’s name; drug name, dosage, and quantity dispensed; instructions for use; precautionary statements; and dispensing date.

Labels must contain the same information found on prescription drug containers dispensed from the pharmacy. This information includes, but is not limited to: dentist’s name, office address, and phone number; patient’s name; drug name, dosage, and quantity dispensed; instructions for use; precautionary statements; and dispensing date.

When the patient has a common name or when there is one or more individual with the same name, or living within the same household with the same name (eg, father and son), two patient identifiers should be included on the label, such as date of birth and address. This may help prevent dispensing the drug to the wrong patient.

Labeling requirements may differ for dispensing individually packaged drugs, such as manufacturer samples, directly to patients. Further, some states require additional information on the label, and some necessitate that dentists who dispense prescription drugs register with the state. Oral health professionals, including dental hygienists and dental assistants, are encouraged to consult their state dental practice acts to determine the requirements for the proper dispensing and labeling of prescription medications. Failure to comply with drug dispensing and labeling laws is a violation of the state dental practice act, which may result in legal and disciplinary actions.

To facilitate this process, labels may be purchased in bulk and then preprinted with the required information, allowing space for the dentist to write in the patient’s name and dispensing date. When it is determined that the drug is necessary for a patient, the dentist completes the label and affixes it to the product. All prescription drugs should be stored in the original packaging from the manufacturer. If a drug is purchased in bulk and the dentist wishes to send some of the drug home with the patient, the dispensed drug must be placed into an appropriate container and labeled accordingly, including the quantity of the drug dispensed.

Many manufacturers of 0.12% chlorhexidine gluconate mouthrinses leave space on their products for the placement of office prescription labels. For prescription fluorides dispensed from the dental office, the label can be affixed either directly onto the bottle or tube, or to the packaging itself.

DRUG IDENTIFICATION

The label on the drug container should always be double-checked prior to administering or dispensing a medication to a patient. This is especially important during a medical emergency, when the stress levels of both patients and staff are high. Prior to administering emergency medications, practitioners should check the label first to verify that the correct medication has been selected. To reduce the risk of error, create a quick reference guide that contains bulleted notes about the drugs in the emergency kit. The notes should be easy to read and quick to interpret. Affix the guide either to the top of the kit or place it within the kit in a spot that is easy to access during an emergency. For example, a note could read, “Chest pain: nitroglycerin tablets: one tablet under tongue every 5 minutes; three doses maximum.” A color-coding scheme also may be used to organize drugs in the emergency kit.8

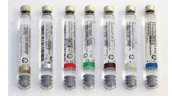

Manufacturers have implemented measures to assist with easy identification of local anesthetic agents by participating in a standardized color-coding scheme adopted by the American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs in 2003.9 Each anesthetic agent is assigned a unique color, which appears on individual cartridges, as well as outside packaging (Figure 1). A 3 mm band of color is located at the stopper end of the cartridge. In addition, lettering on the cartridge follows US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) labeling guidelines for easy readability and drug identification. Dental professionals should always check the color band and read the label on the cartridge prior to inserting it into the syringe to ensure proper drug selection.

There have been documented cases of “mistaken identity,” in which sodium hypochlorite—an irrigant used during endodontic procedures—was accidentally injected into the soft tissues instead of a local anesthetic agent, resulting in tissue and bone necrosis.10,11 Newer delivery vehicles that are visibly different from the glass cartridges used for local anesthetics have helped to eliminate this risk.

There have been documented cases of “mistaken identity,” in which sodium hypochlorite—an irrigant used during endodontic procedures—was accidentally injected into the soft tissues instead of a local anesthetic agent, resulting in tissue and bone necrosis.10,11 Newer delivery vehicles that are visibly different from the glass cartridges used for local anesthetics have helped to eliminate this risk.

The manufacturer of phentolamine mesylate, a vasodilator that reverses the effects of local anesthetic agents, uses color coding to help practitioners easily distinguish it from local anesthetic drugs delivered via the same cartridge design. A bright green label on the cartridge and a blue endcap help prevent medication errors.12 While the majority of states allow dental hygienists to administer local anesthetic agents, only 17 states allow dental hygienists to administer reversal agents.13–15 Dental hygienists should consult their state dental practice acts to verify whether administration of this drug falls within their legal scope of practice.

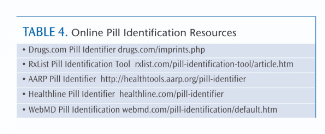

Many software programs are available to assist with drug identification (see Table 4). Individual tablets and capsules are branded with a unique identification code that can be entered into a software system for analysis. Other characteristics, such as pill shape and color, also can be used to filter results.

DOCUMENTATION

Information about prescribed or dispensed medications must be noted in the patient’s record. Documentation should include the drug indication, drug name, dosage, quantity dispensed, number of refills, instructions provided to the patient, precautions, and any special notes given to the pharmacist. If the prescription was phoned or faxed into the pharmacy, the pharmacy location, phone number, and name of the pharmacist or pharmacy technician who took the order also should be documented.

DRUG INVENTORIES

Most dental offices do not keep a significant number of drugs onsite, but it is important for every staff member to be aware of what drugs are available, as well as their standard dosing regimens and indications and contraindications for use. Many dentists have acetaminophen and ibuprofen available to dispense in a single dose for pain relief following a procedure. Many also keep amoxicillin and clindamycin on hand to dispense to patients who require antibiotic premedication prior to scheduled dental procedures.

A staff member should be designated to help monitor the inventory of in-office medications. This ensures that an adequate supply of medication is kept on hand, and to verify that the available drugs have not expired. Monitoring also should include drugs kept in the office medical emergency kit, which often expire at different dates. Expiration dates for in-office fluorides, chlorhexidine mouthrinses, and topical and local anesthetic agents should be monitored, as well.

A recent article by Saraghi and Hersh16 discussed two case reports where lidocaine and benzocaine were detected in the bloodstream and urine of individuals who used them to enhance the nasal numbness produced by cocaine inhalation. Saraghi and Hersh noted that lidocaine and benzocaine are readily available in dental offices, suggesting a potential risk that dental offices may be a source of these substances for adulterating cocaine. They recommend that these agents be monitored closely in the dental practice setting.16

The designated staff member should monitor drugs within the dental office on a monthly basis, with the inventory date and any pertinent findings documented in a log.8 Nitrous oxide and oxygen tanks should be monitored more frequently, depending on how much and how often the gases are used. An adequate oxygen supply must be available at all times.

The designated staff member should monitor drugs within the dental office on a monthly basis, with the inventory date and any pertinent findings documented in a log.8 Nitrous oxide and oxygen tanks should be monitored more frequently, depending on how much and how often the gases are used. An adequate oxygen supply must be available at all times.

Ordering a replacement vial of nitroglycerin tablets after the existing vial has been opened is recommended, as exposure to light degrades the drug. Adopting this habit helps to ensure there is a fresh inventory of this emergency drug for use with patients who develop angina while in the dental office. Some dentists prefer to keep nitroglycerin spray in their emergency kits instead of tablets, as the spray form has a longer shelf life. Epinephrine pens used to counteract anaphylaxis also have a short shelf life, and require frequent replacement.

State dental practice acts are very specific as to the requirements for keeping detailed records and documented inventories if using and dispensing controlled substances in the dental office. These requirements are issued by the DEA and address when and how often a detailed inventory must be completed, nature of the specific drug information for inclusion, and length of time inventory records must be maintained and submitted for review. The inventory typically uses a coding scheme that allows the dentist to track which patients receive the drugs without using common identifiers that violate the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. This requires additional paperwork that must be kept in a secure location. It takes considerable effort to maintain accurate records that comply with state laws regarding the use of controlled substances. Failure to manage appropriate drug inventories for controlled substances is a violation of the state dental practice act and federal DEA requirements, which may result in legal and disciplinary actions.

DRUG STORAGE

All drugs that are used in the dental office should be kept in their original containers, and stored in a secure location removed from patient treatment rooms and common areas. Controlled substances (eg, opiates for sedation) must be kept in a locked cabinet that is only accessible by authorized personnel. Most general dental offices do not need to keep controlled substances onsite. In fact, doing so may increase the potential for theft and other criminal behavior.

Drugs should be stored in an area away from direct sunlight and immune from extreme temperature changes. For example, drugs should not be kept in a cabinet above the autoclave, as the steam and heat that escape during venting significantly raise the temperature of the surrounding area.

Local anesthetic cartridges are kept in the operatories for easy access during patient procedures. Smaller quantities are preferred to ensure that cartridges are used prior to their expiration dates. When refilling the stock, newer cartridges are placed beneath/behind existing cartridges, rotating the cartridges with approaching expiry to the front to prompt immediate use. When possible, cartridges should be stored in their original containers in the treatment area. Excess containers should be kept in a central supply area in their original packaging that displays the expiration date. Expiration dates, which are printed on each cartridge, should be checked prior to administration.

DRUG DISPOSAL

Consumers and professionals need to be informed about how to safely dispose of unused and expired medications. Access to stored medications at home is a contributing factor to prescription medication abuse, which is especially problematic for children and adolescents—and is a leading cause of emergency department visits due to accidental or intentional overdose.17,18 Clinicians must avoid overprescribing and limit quantities of prescribed pain medications and controlled substances in an effort to help combat drug abuse.

Drug disposal by flushing medications down the sink or toilet has led to concerns about negative effects on people and animals through contamination of water supplies and vegetation. There are also concerns about the effects that antibiotics in the water may have on disease-producing pathogens. According to the US Environmental Protection Agency, there is currently no evidence showing adverse human health effects caused by drug residues in the environment. The primary way drugs end up in the water supply is through human excretion of medications that are not fully metabolized, which then enter the environment after passing through waste water treatment plants.19,20

Drugs must be disposed of properly in accordance with local, state, and federal laws. Clinicians and consumers can contact city and county household trash and recycling offices for information about local drug take-back programs, as well as any rules that dictate which medications can be returned. Pharmacists are good resources to assist with identifying take-back programs in the area. The DEA’s Office of Diversion Control maintains a website— deadiversion.usdoj.gov/drug_disposal/takeback — where users can enter a zip code to find a location that accepts drugs for proper disposal. This website also provides information for practitioners about how to properly dispose of unusable or unwanted scheduled substances, by transferring these drugs to an authorized registrant, known as a “reverse distributor.”21

In cities without a take-back program, most medications can be disposed of in the household trash. If not properly sealed, drugs disposed of in this fashion can leak into the environment over time. Hospitals and pharmacies often dispose of drugs through incineration, but this is not always an option for consumers and clinicians in other settings.

The FDA and White House Office of National Drug Control Policy developed federal guidelines to assist with proper drug disposal.18 These guidelines include:

- Follow disposal instructions on the drug label or information that accompany the drug; do not flush medicines down the sink or toilet unless the medication packaging notes that this is acceptable

- Take advantage of community drug take-back programs that allow the public to bring unused drugs to a central location for proper disposal; contact the city or county government household trash and recycling service to see if a take-back program is available; the DEA periodically sponsors National Prescription Drug Take-Back Days

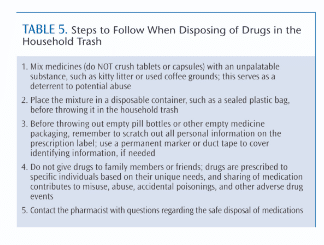

If no disposal instructions are given on the prescription drug labeling and no take-back program is available locally, the medications may be disposed of in the household trash following the specific steps outlined in Table 5.

Inhalers used for respiratory diseases may contain propellants known as chlorofluorocarbons, which damage the ozone layer. These propellants were phased out at the end of 2013. Local trash and recycling offices should be contacted to determine how to properly dispose of these devices, as they may become combustible if punctured or incinerated. Special handling may be required if identified as hazardous waste.19

The FDA has a list of medications, including opioid analgesics, that should be flushed down the sink or toilet, as these drugs may be especially harmful or fatal to people or pets if accidentally ingested, even in a single dose.22 Patients should be advised to follow the disposal recommendations included with the product packaging.

SUMMARY

All dental professionals should consult state dental practice acts for guidance about how to properly prescribe, label, dispense, store, and dispose of medications. These regulations can be incorporated into office procedures for implementation in daily practice. Practitioners must comply with local, state, and federal guidelines. Adherence to proper medication management strategies helps to promote patient safety.

REFERENCES

- Aronson JK. Medication errors: definitions and classification. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;67:599–604.

- Aronson JK. Medication errors: what they are, how they happen, and how to avoid them. QJM. 2009;102:513–521.

- Harold RS. Prescription writing for dentists: ethical and legal guidelines. J Mass Dent Soc. 2012;61:6.

- Dental Software Advisor. Dental ePrescribing: Why and What to Expect. Available at: dentalsoftwareadvisor.com/dental-eprescribing-why-and-what-to-expect. Accessed April 20, 2014.

- Surescripts. Medication Network Services. Available at: surescripts.com/products-and-services/medication-network-services. Accessed April 20, 2014.

- Allscripts. About Allscripts. Available at: allscripts.com/en/company/about-us.html.Accessed April 20, 2014.

- Kelly WN. Including indications when writing prescriptions. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2011;68:1397.

- Roberson JB. Emergency kit strategies for the dental office. Available at: dentistrytoday.com/ emergency-medicine/6767-emergency-drug-kit-strategies-for-the-dental-office. Accessed April 20, 2014.

- American Dental Association. Color Coding of Local Anesthetic Cartridges. Anesthesia and Sedation. Available at: ada.org/2516.aspx?currentTab=2#color. Accessed April 20, 2014.

- Gursoy UK, Bostanci V, Kosger HH. Palatal mucosa necrosis because of accidental sodium hypochlorite injection instead of anaesthetic solution. Int Endod J. 2006;39:157–161.

- Pontes F, Pontes H, Adachi P, Rodini C, Almeida D, Pinto D Jr. Gingival and bone necrosis caused by accidental sodium hypochlorite injection instead of anaesthetic solution. Int Endod J. 2008;41:267–270.

- Logothetis D. Local Anesthetic Agents: a Review of the Current Options for Dental Hygienists. Available at: cdha.org/?wpdmact=process&did=NzkuaG90bGluaw==. Accessed April 20, 2014.

- Hersh EV, Lindemeyer RG. Phentolamine mesylate for accelerating recovery from lip and tongue anesthesia. Dent Clin North Am. 2010;54:631–642.

- Tavares M, Goodson JM, Studen-Pavlovich D, et al. Reversal of soft-tissue local anesthesia with phentolamine mesylate in pediatric patients. J Am Dent Assoc. 2008;139:1095–1104.

- Hersh EV, Moore PA, Papas AS, et al. Reversal of soft-tissue local anesthesia with phentolamine mesylate in adolescents and adults. J Am Dent Assoc. 2008;139:1080–1093.

- Saraghi M, Hersh EV. Potential diversion of local anesthetics from dental offices for use as cocaine adulterants. J Am Dent Assoc. 2014;145:256–259.

- Partnership for a Drug Free America. The Partnership Attitude Tracking Study (PATS). Teens 2008 Report. Available at: drugfree.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Full-Report-FINAL-PATS-Teens-2008_updated.pdf. Accessed April 20, 2014.

- White House Office of National Drug Control Policy. Prescription Drug Abuse. Available at: whitehouse.gov/ondcp/prescription-drug-abuse. Accessed April 20, 2014.

- United States Food and Drug Administration. Consumer Health Information. How to Dispose of Unused Medications. Available at: fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/ResourcesForYou/Consumers/BuyingUsingMedicineSafely/UnderstandingOver-the-CounterMedicines/ucm107163.pdf. Accessed April 20, 2014.

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. How to Dispose of Medicines Properly. Available at: water.epa.gov/scitech/swguidance/ppcp/upload/ppcpflyer.pdf. Accessed April 20, 2014.

- United States Food and Drug Administration. Medicines Recommended for Disposal by Flushing. Available at:fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/ResourcesForYou/Consumers/BuyingUsingMedicineSafely/EnsuringSafeUseofMedicine/SafeDisposalofMedicines/ UCM337803.pdf. Accessed April 20, 2014.

- United States Drug Enforcement Administration. Drug Disposal Information. Available at: deadiversion.usdoj.gov/drug_disposal/index.html. Accessed April 20, 2014.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. May 2014;12(5):51–55.