Joint Protection

Tips for treating and preventing osteoarthritis of the thumb, a common ailment among dental hygienists.

Osteoarthritis (OA) affects nearly 27 million people in the United States, and is the number one cause of disability among older adults in the country.1 Also known as degenerative joint disease, OA is currently the most common type of arthritis.1 Arthritis is more common among women, those older than 45 years, people with obesity, those with previous injuries to a joint, and those who experience repetitive motion of the joints from work or athletics. Genetics may also be a significant contributing factor. Arthritis is most common in the knees, hips, and hands.2 Mid- to late-career dental hygienists who perform repetitive tasks with little variation of movement may be especially susceptible to OA of the hands.

TABLE 1. OSTEOARTHRITIS SYMPTOMS.

- Pain at the base of the thumb.

- Weakness (which may be due to pain).

- Swelling in the hand and wrist.

- Stiffness (especially in the morning).

- Loss of range of motion, limiting functional use of the thumb.

- Crepitus or a crackling noise with movement.

- Dropping things due to pain, weakness, or poor endurance.

- Enlarged bony protuberance at the base of the thumb, indicating over-growth of bone, which may be the body’s way of stabilizing an unstable joint.

Perhaps due to its mobile nature, OA of the hand frequently involves the thumb,3 or more specifically, the trapeziometacarpal or “basal” joint, located at the base of the thumb, less than an inch distal to the wrist (Figure 1). Thumb basal joint OA is common and can be disabling.4-6 In a study of 143 postmenopausal women, 25% had evidence of basal joint arthritis. Of those diagnosed with basal joint arthritis, 28% reported pain at the base of the thumb.7

SYMPTOMS

Osteoarthritis results in a breakdown of the cartilage that covers and protects the ends of bones within a joint. Table 1 lists OA symptoms. The typical patient with osteoarthritis is a woman between the ages of 50 years and 70 years who complains of thumb pain that originally worsened with activity.8 She reports decreased use of the hand for activities of daily living, weakened grip strength, and decreased manual dexterity. Use of the thumb for such activities as writing, opening jars, or carrying heavy objects between the thumb and fingers causes pain. There is weakness noted while pinching objects between the thumb and fingers. Symptoms may progress to feelings of stiffness and cramping, and in later stages, pain may exist at rest.8

TREATMENT

The first course of action when OA is suspected is to see a physician. The physician may decide that a referral to an orthopedic surgeon who specializes in hands is appropriate. An X-ray is usually needed to diagnose this condition. It will show a narrowing of the joint space, indicating a loss of articular cartilage. Although there is no cure for OA, several treatment options are available depending on the level of severity.

The first course of treatment usually involves oral medications including nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). NSAIDs help ease the pain in addition to relieving the inflammation that so often limits joint function. Next up is typically a referral to either physical therapy or occupational therapy. A licensed therapist who is also a certified hand therapist (CHT) is the best option. A CHT must have a minimum of 5 years of clinical experience, including 4,000 hours treating hand patients. They must also pass a rigorous, comprehensive examination focusing on upper extremity dysfunction. There are currently more than 5,000 CHTs in the United States.9

The hand therapist will probably advise the use of ice or heat as needed for pain, and to rest the thumb and avoid excessive use. This may involve putting the thumb in a splint. Using a splint at night helps to align the joint in a more natural posture, therefore avoiding stressful positions. The splint can also be worn during the day, especially when performing repetitive or strenuous activities that involve the hands. The splint should not be worn all the time because it may cause joint stiffness and contracture. A thumb spica splint (Figure 2) is commonly used for this condition. However, custom splints can also be designed in which the materials are heated and then molded to fit the exact curvatures of the hand. Research demonstrates that use of a splint for 6 weeks reduces symptoms of basal joint arthritis, but is more effective in the early stages of the disease.10 A 7-year longitudinal study showed that a combination of hand therapy and splinting helped 70% of subjects avoid surgical intervention.11

Ultrasound treatment is often used by hand therapists. During this procedure, an ultrasound machine is used to generate high-frequency sound waves that penetrate the skin through a medium of water-based gel. Ultrasound can provide deep heating to subcutaneous tissues, penetrating as much as 5 cm beneath the skin. This is believed to improve blood circulation, provide pain relief, promote healing, and increase the flexibility of soft tissues allowing more joint range of motion. Therapeutic ultrasound can also be used to deliver anti-inflammatory medications. Typically, a concentrated solution of hydrocortisone cream is massaged into the skin prior to administration of the ultrasound treatment.12

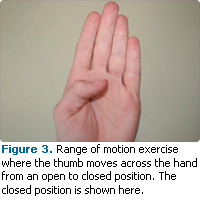

Hand therapy for basal joint arthritis also involves therapeutic exercise and activities to restore range of motion, strength, and function. Thumb range of motion exercises (Figure 3) should not be forced, but performed in a limited, pain-free movement to help slowly restore normal function. Strengthening exercises (Figures 4 and 5) will help rebuild weakened muscles. Functional activities are used to regain coordination (Figure 6).

|

|

Researchers have attempted to study the effects of exercise on the symptoms of OA. In a study of 76 older adults with OA of the hand, half of the individuals received a customized home program to perform daily for 16 weeks including hand strengthening and range of motion exercises. The other half received a placebo treatment of daily home application of a nonmedicated moisturizing lotion. Results indicated that grip and pinch strength improved in the exercise group but not in the placebo group. No changes were noted in self-reported pain, stiffness, or physical function.13

There is growing interest in alternative therapies for arthritis. The Arthritis Foundation promotes a simplified version of tai chi to improve the quality of life for arthritis patients. This method includes agile steps and exercises that may improve mobility, breathing, and relaxation.14 Another alternative therapy is yoga, an ancient form of exercise that involves deep, relaxing stretches. In a study of patients with OA of the hands, yoga was shown to decrease pain with movement, improve range of motion, and decrease tenderness after an 8-week trial compared with a control group that received no treatment.15

For individuals in the advanced stages of basal joint OA, surgical intervention may be indicated. A joint fusion may alleviate pain and inflammation because it essentially removes the involved joint. The downside of this surgery, however, is that movement is no longer possible in this area of the hand. Individuals seeking stability, strength, and elimination of painful symptoms may select this option. Those who wish to maintain normal use of the hand, including manual dexterity and manipulation of objects, will be more interested in joint replacement.

|

|

The most common form of basal joint replacement for the thumb is tendon interposition arthroplasty.3 This surgery involves removal of the trapezium bone, a small wrist bone that is the most proximal component of the joint. The trapezium bone is replaced with soft tissue borrowed from a tendon in the individual’s own wrist. The alternative is total joint replacement using a prosthesis or artificial joint. A study published by the American Society for Surgery of the Hand compared both of these surgical approaches by following patients for 12 months after surgery.16 The authors concluded that joint replacement surgery with prosthesis resulted in faster and better pain relief, stronger grip functions, improved range of motion, and faster convalescence, reaching levels of strength and range of motion comparable to the noninvolved hand. There were no signs of loosening of the prostheses and complication rates were similar between the two surgical approaches. Another study included 43 subjects who reported a 70% satisfaction rate with joint replacement surgery using a prosthesis. Good range of motion, grip, and pinch strength recovery also were reported in this study, however, the authors did report loosening in 44% of these implants.17 Both surgical approaches involve post-operative casting/splinting for 4 weeks to 6 weeks followed by a structured rehabilitation program. Individuals considering surgical intervention for basal joint arthritis should consult a qualified hand surgeon and discuss the pros and cons of all surgical alternatives in order to make an informed decision.

PREVENTION

As with all chronic disease, prevention is the ultimate goal. Unfortunately, the causes of OA are not yet fully understood. Experts have called for more research and action for the primary prevention of OA.18 Current research does offer some hope. Studies of the relationship between muscle weakness and OA suggest that lack of exercise and activity may actually lead to arthritis rather than cause it.19 Weak muscles don’t stabilize joints well, which allows excessive movement and shear forces to build up, leading to wear and tear of the articular cartilage. Though far from conclusive, this theory may offer further evidence of the need to maintain proper fitness. Keeping muscles strong and flexible can only help improve joint health. Regular exercise also will help individuals avoid being overweight, a risk factor for OA. Dental hygienists should keep hand musculature strong and flexible, however excessive repetitive use of the thumb outside of work should be avoided.

REFERENCES

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Arthritis. Available at: www.cdc.gov/arthritis. Accessed March 13, 2011.

- Arthritis Foundation. Osteoarthritis: the basics about this disease that affects 27 million americans. Available at: www.arthritis.org/osteoarthritis.php. Accessed March 13, 2011.

- Swigart CR. Arthritis of the base of the thumb. Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2008;1:142-146.

- Barron OA, Blickel SZ, Eaton RG. Basal joint arthritis of the thumb. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2000;8:314-323.

- Wilder FV, Barrett JP, Farina EJ. Joint-specific prevalence of osteoarthritis of the hand. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2006;14:953-957.

- Sodha S, Ring D, Zurakowski D, Jupiter JB. Preva lence of osteoarthritis of the trapezio – metacarpal joint. J Bone Joint Surg. 2005;87: 2614-2618.

- Armstrong AL, Hunter JB, Davis TR. The prevalence of degenerative arthritis of the base of the thumb in post-menopausal women. J Hand Surg Br. 1994;19:340-341.

- Matullo KS, Ilyas A, Thoder JJ. CMC arthroplasty of the thumb: a review. Hand (NY). 2007;2:232–239.

- Hand Therapy Certification Commission. Who is a certified hand therapist? Available at: www.htcc.org/about/index.cfm. Accessed March 13, 2011.

- Swigart CR, Eaton RG, Glickel SZ, Johnson C. Splinting in the treatment of arthritis of the first carpometacarpal joint. J Hand Surg. 1999;24:86-91.

- Berggren M, Joost-Davidsson A, Lindstrand J. Reduction in the need for operation after conservative treatment of osteoarthritis of the first carpometacarpal joint: a seven year prospective study. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 2001;35:415-417.

- MD Guidelines. Therapeutic Ultrasound. Available at: www.mdguidelines.com/ultrasoundtherapeutic. Accessed March 13, 2011.

- Rogers MW, Wilder FV. Exercise and hand osteoarthritis symptomatology: a controlled crossover trial. J Hand Ther. 2009;22:10-18.

- Arthritis Foundation. Tai Chi Program. Available at: www.arthritis.org/tai-chi.php. Accessed March 13, 2011.

- Garfinkel MS, Schumacher HR Jr, Husain A, Levy M, Reshetar RA. Evaluation of a yoga-based regimen for treatment of osteoarthritis of the hands. Rheumatol. 1994;21:2341-2343.

- Ulrich-Vinther M, Puggaard H, Lang B. Prospective 1-year follow-up study comparing joint prosthesis with tendon interposition arthroplasty in treatment of trapeziometacarpal osteoarthritis. J Hand Surg Am. 2008;33:1369-1377.

- De Smet L, Sioen W, Spaepen D, Van Ransbeeck H. Total joint arthroplasty for osteoarthritis of the thumb basal joint. Acta Orthop Belg. 2004;70:19-24.

- Hochberg MC. Opportunities for the prevention of osteoarthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2010;39:321-322.

- Valderrabano V, Steiger C. Treatment and prevention of osteoarthritis through exercise and sports. J Aging Res. 2010;6:374653.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. April 2011; 9(4): 44, 46, 48.