Sunstar Spotlight: Improving The Health of Patients With Diabetes

Achieving positive outcomes in this population requires a multidisciplinary approach.

INTRODUCTION

Sunstar’s mission is to improve overall health by helping people achieve strong, healthy teeth and gums. We are committed to providing innovative, high-quality oral health care products to consumers and professionals. Furthermore, Sunstar is a leader in educating and motivating individuals to make lifelong commitments to oral health. In support of our mission, Sunstar partnered with Harvard Medical School’s Joslin Diabetes Center to create the Joslin Sunstar Diabetes Education Initiative. We also acknowledge dental professionals via award programs such as the World Dental Hygienist Award (see page 23 for a list of this year’s recipients) and recently sponsored a publication on the association between periodontitis, atherosclerosis, and diabetes. Sunstar was one of the first supporters of scientific research into the oral-systemic link more than 30 years ago. Since then, we have hosted many symposia in collaboration with key opinion leaders to educate dental and medical professionals.

—Jackie L. Sanders, RDH, BS

Manager, Professional Relations Sunstar Americas Inc

Diabetes mellitus is a chronic disease that affects more than 422 million people in all parts of the world.1 The latest National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey reported that 14.3% of adults in the United States have diabetes. In addition, about 40% have prediabetes or elevated blood glucose levels. Individuals with prediabetes are at increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes.2

GUNILLA ELAM / SCIENCE SOURCE

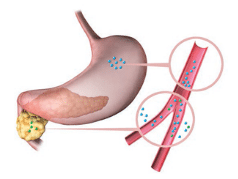

Diabetes is a metabolic disease in which the body fails to properly metabolize glucose, leading to elevated levels of glucose in the bloodstream. There are three main categories of diabetes: type 1, type 2, and gestational diabetes.3 Type 1, which accounts for 5% to 10% of all cases, is an autoimmune disease in which the body fails to produce insulin in the pancreas (Figure 1). The most common category of diabetes is type 2, which is caused by insulin resistance and/or deficiency in insulin production and comprises 90% to 95% of all cases (Figure 2). Gestational diabetes affects pregnant women and occurs when the body does not produce enough insulin to lower blood glucose levels. Individuals with a history of gestational diabetes have an increased risk for developing type 2 diabetes.4

Ethnic minorities and older adults are at elevated risk of developing diabetes. The latest national data show that 20.6% to 22.6% of Asian, black, and Hispanic Americans have diabetes, while 11.3% of non-Hispanic whites have it.2 Ethnic minorities with diabetes are more likely to struggle with effective disease management and experience reduced health outcomes.4 Diabetes incidence increases with age. One third of those age 65 or older have diabetes, and their risk for other comorbidities is also higher than other age groups.2,5

Maintaining blood glucose levels in a desirable range is important in preventing and delaying the development of diabetes-related complications. Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) is often used as an indicator of long-term glycemic control. It reflects the average blood glucose concentration over the preceding 2 months to 3 months. Generally, keeping HbA1c levels at less than 7% is recommended.6 HbA1c goals may be adjusted based on factors such as age and other comorbidities. Poorly controlled diabetes increases the risk and severity of complications, including periodontal diseases.7

DIABETES AND ORAL HEALTH

GUNILLA ELAM / SCIENCE SOURCE

Diabetes is a risk factor for periodontal diseases. People with diabetes are three times more likely to develop periodontitis than those who do not have diabetes.7 Risks for gingivitis and oral inflammation are also increased.8 Diabetes may cause xerostomia, thus, raising the risk of dental caries.9 Individuals with diabetes are more likely to experience tooth loss.10

While diabetes negatively affects oral health, periodontitis also adversely impacts diabetes control. Severe periodontitis increases the risk of poor glycemic control. A meta-analysis showed that individuals who received periodontal treatment experienced statistically significant improvements in HbA1c levels (0.4%). Systemically, chronic periodontitis may also worsen existing cardiovascular and kidney disease in patients with diabetes.7

THE ROLE OF NUTRITION

Achieving an optimized glycemic goal is important for successful management of diabetes and its comorbidities such as oral health. A healthy diet is a critical component of reaching glycemic goals and it is an essential self-care behavior that impacts oral health.11

Foods provide macronutrients, micronutrients, fiber, and the phytonutrients needed for energy, growth, and sustenance. Carbohydrates, fats, and proteins are the primary macronutrients that provide the body with energy. Micronutrients (vitamins and minerals), fiber, and phytonutrients are also vital to health. These nutrients play an important role in overall health and diabetes management.

Among the three primary macronutrients, carbohydrates have the most significant impact on blood glucose. The amount of carbohydrates consumed affects post-prandial blood glucose levels.12,13 High carbohydrate intake without adequate insulin to metabolize blood glucose levels leads to hyperglycemia. A consistent pattern of hyperglycemia may increase HbA1c, worsening diabetes control.14

Along with the quantity consumed, the type of carbohydrates also influences the post-prandial glycemic level.12 Glycemic index measures the effect of carbohydrate-containing foods on post-prandial blood glucose.15 The higher the glycemic index of a particular food, the more rapid the variation in blood glucose levels.11,15 Consuming carbohydrates with high glycemic indeces may lead to a raised post-prandial blood glucose level,16 and may contribute to a high HbA1c and less satisfactory diabetes control.14 Conversely, choosing foods that have low glycemic indeces may improve long-term blood glucose control.17

Fat also affects post-prandial blood glucose levels. Studies show that consuming a high-fat meal increases blood glucose levels.16 Without adequate insulin to lower the blood glucose level, HbA1c may be adversely affected in the long-term. Additionally, fat delays gastric emptying, leading to a reduction of early glucose response and late post-prandial hyperglycemia.16 Without properly matching the amount and timing of insulin injection, patients may experience blood glucose swings from hypoglycemia to hyperglycemia.

The total amount of macronutrients consumed affects blood glucose levels. Reducing the consumption of macronutrients lowers caloric intake and may lead to weight loss. For many people with diabetes, especially type 2, losing weight improves diabetes control.18

Patients with diabetes who use insulin or certain types of oral hypoglycemic medications (eg, sulfonylureas, meglitinides) may experience hypoglycemia. Hypoglycemia is treated by promptly consuming 15 g to 20 g of simple, fermentable carbohydrates,6 such as glucose tablets, glucose gel, juice, soda, sugar, or honey. Patients with an erratic blood glucose pattern and frequent hypoglycemia increase their exposure to these fermentable carbohydrates, elevating their risk of tooth decay.19

Ensuring a balanced intake of macronutrients is important in achieving a healthy weight, maintaining a more steady blood glucose pattern, and improving diabetes control. Consuming an adequate and balanced diet also promotes systemic and oral health. Good nutrition is imperative to diabetes management and the prevention of diabetes-related complications.19

Tooth loss and xerostomia are seen more frequently among patients with diabetes.9,10 These conditions also hinder an individual’s ability to chew food, which often leads to the increased consumption of soft and easy-to-chew foods that may be cariogenic.19–21 Foods that have a low glycemic index are often high in fiber and more difficult to chew, such as vegetables, legumes, and whole grains. Dietary restrictions can also compromise the quality of nutrients consumed, impacting overall health.19 Xerostomia may further worsen oral health by increasing the risk of oral infections and caries.22

A two-way relationship between diabetes and periodontal diseases is well-established.7 Nutrition plays a vital role in both systemic health and oral health. There is increased awareness among physicians, dentists, and other medical and dental professionals about these interrelationships. Screening for diabetes in dental offices, assessing oral health in medical settings, and referring patients with diabetes for regular dental appointments are not yet routine practices.

RAISING AWARENESS OF THE ORAL-SYSTEMIC HEALTH LINK

Joslin Diabetes Center, an affiliate of Harvard Medical School in Boston, is dedicated to preventing, treating, and curing diabetes. The clinic at Joslin Diabetes Center has integrated a set of oral health screening questions in its electronic medical system. Providers, including diabetes educators, at the Joslin Diabetes Center initiate conversations with patients regarding the oral-systemic relationship and provide education on the importance of maintaining oral health and glycemic control.

To increase awareness of the link between diabetes and periodontal diseases among health care professionals on a global scale, Joslin Diabetes Center and Sunstar Foundation jointly established the Joslin-Sunstar Diabetes Education Initiative (JSDEI). This initiative focuses on sharing up-to-date scientific evidence regarding the bidirectional links between oral and systemic health. Since its establishment in 2008, JSDEI has held 20 global symposia in the United States, Japan, China, Singapore, Switzerland, Italy, Germany, and Spain. More than 7,000 dental and medical professionals have attended these symposia, including dentists, physicians, dental hygienists, nurses, dietitians, researchers, pharmacists, and medical and dental students.

Renowned scientists and clinicians in both dentistry and medicine provide the education at these symposia. Attendees receive an overview of the pathophysiology of periodontal diseases, diabetes, and diabetes-related complications, in addition to a survey of the research surrounding obesity, inflammation, microbiota, and diabetes treatment. Furthermore, the collaborative roles of dental and medical professionals are emphasized. To encourage referrals for the diagnosis and screening of these diseases, a discussion of insurance/reimbursement is also provided.

Attendees also receive sample assessment questionnaires to encourage medical and dental professionals to screen for periodontal diseases and diabetes in their offices. In specific symposia, diabetes care and starter meal plans are provided. These practical tools are designed to initiate a conversation with patients on the risk factors for both diseases, while prompting clinicians to make appropriate referrals for definitive diagnoses.

In addition, Joslin Diabetes Center and Sunstar Foundation have co-published two booklets on diabetes and oral health—one for professionals and one for patients.23,24 The professional version includes the latest scientific information, screening tools, and treatment methods. The patient booklet provides basic information about diabetes, periodontal diseases, and the signs and symptoms of each. A self-assessment tool for identifying periodontal risk is also included.

CONCLUSION

Oral and systemic health are closely related. For dental professionals, interviewing patients about their medical histories—especially those with periodontal diseases—and referring patients at elevated risk of diabetes to appropriate medical providers support early diagnoses. For medical professionals, assessing the oral health of patients with diabetes and referring them for dental care may help limit oral health problems that, in turn, may affect diabetes and its management. n

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The author would like to thank William C. Hsu, MD, for his help with this manuscript.

References

- World Health Organization. Global Report on Diabetes. Available at:who.int/diabetes/global-report/en. Accessed April 20, 2016.

- Menke A, Casagrande S, Geiss L, Cowie CC. Prevalence of and Trends indiabetes among adults in the United States, 1988-2012. JAMA.2015;314:1021–1029.

- American Diabetes Association. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes.Diabetes Care. 2016;9(Suppl 1):S13–S22.

- Le H, Wong S, Iftikar T, Keenan H, King GL, Hsu WC. Characterization offactors affecting attainment of glycemic control in Asian Americans withdiabetes in a culturally specific program. Diabetes Educ. 2013;39:468–477.

- Kirkman MS, Briscoe VJ, Clark N, et al. Diabetes in older adults: aconsensus report. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:2342–2356.

- American Diabetes Association. Glycemic targets. Diabetes Care.2016;39(Suppl 1):S39–S46.

- Preshaw PM, Alba AL, Herrera D, et al. Periodontitis and diabetes: a twowayrelationship. Diabetologia. 2012;55:21–31.

- Ryan ME, Carnu O, Kamer A. The influence of diabetes on the periodontaltissues. J Am Dent Assoc. 2003;134(Suppl 1):34S–40S.

- Sreebny LM, Yu A, Green A, Valdini A. Xerostomia in diabetes mellitus.Diabetes Care. 1992;15:900–904.

- Patel MH, Kumar JV, Moss ME. Diabetes and tooth loss: an analysisof data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey,2003-2004. J Am Dent Assoc. 2013;144:478–485.

- American Association of Diabetes Educators. AADE7 self-care behaviors.Diabetes Educ. 2008;34:445–449.

- Sheard NF, Clark NG, Brand-Miller JC, et al. Dietary carbohydrate (amountand type) in the prevention and management of diabetes: a statement bythe American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:2266–2271.

- Franz MJ, Powers MA, Leontos C, et al. The evidence for medicalnutrition therapy for type 1 and type 2 diabetes in adults. J Am Diet Assoc.2010;110:1852–1889.

- Monnier L, Colette C. Contributions of fasting and postprandial glucoseto hemoglobin A1c. Endocr Pract. 2006;12(Suppl 1):42–46.

- Bhupathiraju SN, Tobias DK, Malik VS, et al. Glycemic index, glycemicload, and risk of type 2 diabetes: results from 3 large US cohorts and anupdated meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;100:218–232.

- Bell KJ, Smart CE, Steil GM, Brand-Miller JC, King B, Wolpert HA. Impact offat, protein, and glycemic index on postprandial glucose control in type 1diabetes: implications for intensive diabetes management in the continuousglucose monitoring era. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:1008–1015.

- Brand JC, Colagiuri S, Crossman S, et al. Low-glycemic index foodsimprove long-term glycemic control in NIDDM. Diabetes Care. 1991;14:101.

- Shantha GPS, Kumar AA, Kahan S, Cheskin LJ. Association betweenglycosylated hemoglobin and intentional weight loss in overweight andobese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a retrospective cohort study.Diabetes Educ. 2012;38:417–426.

- Touger-Decker R, Mobley C, Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Positionof the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: oral health and nutrition. J AcadNutr Diet. 2013;113:693–701.

- Brennan DS, Spencer AJ, Roberts-Thomson KF. Tooth loss, chewing abilityand quality of life. Qual Life Res. 2008;17:227–235.

- Chauncey HH, Muench ME, Kapur KK, Wayler AH. The effect of the lossof teeth on diet and nutrition. Int Dent J. 1984;34:98–104.

- Greenspan D. Xerostomia: diagnosis and management. Oncology(Willston Park). 1996;10(3 Suppl):7–11.

- Cheung S, Hsu WC, King GL, Genco RJ. Periodontal disease—its impact ondiabetes and glycemic control. Joslin Diabetes Center. Available at:aadi.joslin.org/en/Education%20Materials/99.PeriodontalDisease-ItsImpactOnDiabetesAndGlycemicControl-EN.pdf. Accessed April 13, 2016.

- Cheung S, Hsu WC, King GL, Genco RJ. Diabetes and dental health—understanding the connection. Joslin Diabetes Center. Available at:aadi.joslin.org/en/Education%20Materials/99.DiabetesAndDentalHealth-UnderstandingTheConnection-EN.pdf. Accessed April 20, 2016.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. May 2016;14(05):19–22.