GEORGE DOYLE / STOCKBYTE / THINKSTOCK

GEORGE DOYLE / STOCKBYTE / THINKSTOCK

Improve Oral Health During Pregnancy

Receiving professional dental care during pregnancy is critical to maintaining oral health.

This course was published in the March 2016 issue and expires March 31, 2019. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Discuss the importance of maintaining oral health throughout pregnancy.

- Identify possible oral complications during pregnancy.

- Explain appropriate dental care for pregnant patients.

- List oral hygiene recommendations for this population.

Despite strong evidence supporting the benefits of dental care during pregnancy, many health care providers and expectant mothers defer diagnostic, preventive, and restorative dental treatment.4,7–9 According to 2004 to 2006 data from the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System, only 44% of women reported receiving professional dental care while they were pregnant.8 Pregnant women may avoid receiving oral care because of time constraints, low oral health literacy, fear that dental treatment during pregnancy is unsafe, lack of dental insurance, or difficulty accessing care. Others mistakenly believe that dental caries, bleeding gums, and other dental problems are unavoidable during pregnancy.10

Prenatal care providers remain inconsistent in recommending oral health care for their pregnant patients. A 2007 survey of obstetricians showed that while 84% of respondents considered periodontitis an important risk factor for adverse pregnancy events, 49% rarely or never recommended dental exams to their pregnant patients.11

In response to the need for practice standards, the Oral Health Care During Pregnancy: A National Consensus Statement was developed by the United States Maternal and Child Health Bureau in collaboration with the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and American Dental Association.7 The guidelines state that oral health professionals should assess every pregnant woman’s oral health; advise pregnant patients on oral health care needs; work in collaboration with prenatal care health professionals; provide oral disease management and necessary treatment; offer support services; and work to improve oral health services in the community. The guidelines reinforce that oral health care during pregnancy is safe and that women should be encouraged to seek dental care, practice good oral hygiene at home, and eat a healthy diet.7,12

RISK AND PREVENTIVE FACTORS

Pregnant women with periodontitis are at increased risk of preeclampsia, preterm birth, gestational diabetes, and LBW babies.4,12–17 A causal link between periodontitis and LBW has not been identified; however, research has established an association between inflammation in the oral cavity and LBW and/or preterm delivery.18–20 Infections are estimated to account for 30% to 50% of all premature deliveries.18–20 Bacterial infections and inflammation trigger production of infection-fighting chemicals that may impair fetal development, dilate the cervix, and trigger uterine contractions. Pathogenic oral bacteria that enter the bloodstream may invade the amniotic sac, leading to adverse pregnancy outcomes. Inflammation can also cause the placental membranes to be more fragile, which may lead to the initiation of preterm labor. Research has also demonstrated that women who had preterm births had increased levels of PGE2 in the gingival crevicular fluid compared to those whose babies were of normal birth weight.17–20 PGE2 is an inflammatory mediator often associated with the initiation of labor. These studies also found greater numbers of the periodontal pathogens Bacteroides forsythus, Porphyromonas gingivalis, Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans, and Treponema denticola in women who delivered premature babies.17–20

Two randomized clinical trials looked at the association between pregnancy outcomes and chronic periodontitis. They both followed women who received treatment for periodontitis during pregnancy.21,22 Results showed that treatment for periodontitis during pregnancy displayed no statistically significant effects on the rates of pre-term delivery, despite trends in that direction. The studies did reinforce that receiving dental care during pregnancy is safe.21

ORAL COMPLICATIONS

Oral complications during pregnancy comprise an increased likelihood and severity of gingivitis, ulcerations of the gingival and oral tissues, pyogenic granulomas, tooth erosion, xerostomia, and excessive salivation.17,23 Pregnancy gingivitis, which is caused by gingivae’s exaggerated immunological response to plaque-biofilm, is the most common complication. Oral hygiene plays an essential role in preventing gingivitis and the condition is exacerbated if self-care does not improve. While clinical signs usually subside after pregnancy, resolution is dependent on oral hygiene habits. Oral hygiene education and regular dental appointments during pregnancy can help patients prevent this complication.

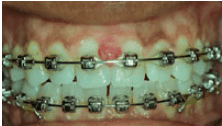

RICARDO PADILLA, DDS, AND SAM NORRIS, DMD

Pyogenic granuloma, also referred to as pregnancy granuloma, occurs in approximately 5% of pregnancies and is typically seen in conjunction with local irritants such as overhanging dental restorations and calculus deposits (Figure 1).23 Granulomas are benign gingival lesions that rarely involve bone loss and are commonly located in the maxillary anterior areas on interdental papilla.24 They appear as a soft, pedunculated, reddish-purple edematous masses that may show spontaneous bleeding and tenderness. Granulomas are most common following the first trimester. Resolution typically occurs within several months after pregnancy ends. Excision may be indicated if the lesion interferes with oral functions; however, recurrence rates are high.24

Patients with morning sickness that includes vomiting over an extended period may experience demineralization and acid erosion of enamel surfaces. Pregnant women may also develop tooth mobility without the presence of periodontitis.17 This is thought to be caused by increased levels of progesterone and estrogen. It typically resolves after pregnancy, unless periodontitis has reduced bone levels to a degree where the teeth have inadequate bony support.

SAFETY OF DENTAL TREATMENT

Current evidence and practice guidelines assert that dental treatment is safe throughout pregnancy.5,7,25–27 A 2015 study showed no indication that exposure to dental care or local anesthesia during pregnancy was associated with increased risk for health problems in offspring.5 Another study that reviewed the safety of dental treatment in pregnant women included 823 pregnant women diagnosed with periodontitis.25 The women were randomly assigned to receive scaling and root planing completed at either 13 weeks, 21 weeks, or post-partum. The researchers also evaluated the subjects for other dental problems such as caries, fractured teeth, or abscessed teeth. There were 351 women who received such essential dental treatment at intervals that ranged from 13 weeks to 21 weeks of pregnancy. If needed, participants received topical and/or locally injected anesthesia. No differences were seen when comparing the groups, and the study concluded that essential dental treatments were not associated with increased risks for adverse pregnancy events or outcomes.29

DENTAL TREATMENT

Treatment rendered during pregnancy should be directed at controlling disease, maintaining health, and preventing oral disease. An assessment comprised of medical history, dental history, risk assessment, nutritional analysis, and clinical examination should be conducted in order to help guide the patient’s treatment plan.7 Patients with health concerns or those at increased risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes may require consultation with their prenatal care providers.

Elective treatments—such as restorative, preventive, and periodontal care—may be performed safely throughout pregnancy.7 Clinicians should use standard practices when placing restorative materials. While there is debate regarding the safety of placing amalgam restorations during pregnancy, no research has found the practice to be unsafe. Numerous studies have examined mercury-amalgam exposure during pregnancy and have not reported any toxicity, increases in birth defects, adverse neurologic sequelae, increased rates of spontaneous abortions, or decreased fertility.27–30 Clinicians can reduce mercury vapor levels by using rubber dams and high-volume suction devices.7

The American Academy of Periodontology asserts that diagnosis and periodontal classification are important in pregnant patients. Overall health and risk factors for periodontitis should be thoroughly evaluated and reviewed with each patient. Patient education and periodontal therapy can be provided with the goal of establishing and maintaining periodontal health.17,31

Emergency palliative dental health care services should be performed at any time during pregnancy for pain relief and control of infection.7 The dental team should collaborate with a patient’s obstetrician to determine the best options for pain relief, if needed.

According to the American College of Radiology, no single diagnostic radiograph emits a radiation dose significant enough to pose a threat to fetus health.26,32 Evidence demonstrates that a fetal dose less than 10 milligray has no developmental effects on the fetus.33 As such, necessary dental radiographs are considered safe during pregnancy, but appropriate justification is necessary.7,26,34 Use of digital imaging and rectangular collimation helps reduce radiation exposure. Shielded collimation, filtration, and application of a lead apron with a thyroid collar and a second lead apron over the back can also prevent secondary radiation from reaching the abdomen. Oral health professionals should follow the “as low as reasonably achievable” principle and use a conservative approach, only exposing radiographs when necessary.26,34

While many oral health professionals are hesitant to deliver local anesthesia during pregnancy, it is safe.5,7 Hagai et al5 completed a prospective comparative cohort study that found no reason pregnant women shouldn’t receive local anesthesia. Additional studies, as well as the Oral Health Care During Pregnancy National Consensus Statement, concur that local anesthesia can be safely administered during pregnancy.7,27

The use of nitrous oxide during pregnancy, however, is controversial. Long-term exposure to nitrous oxide may be linked to miscarriages and birth defects. Short-term exposure has not been shown to cause harm. Nevertheless, nitrous oxide should be used with caution. The Oral Health Care During Pregnancy National Consensus Statement notes that nitrous oxide (30%) may be used during pregnancy when topical or local anesthesia is inadequate. When its use is anticipated, the patient’s prenatal care provider should be consulted.7

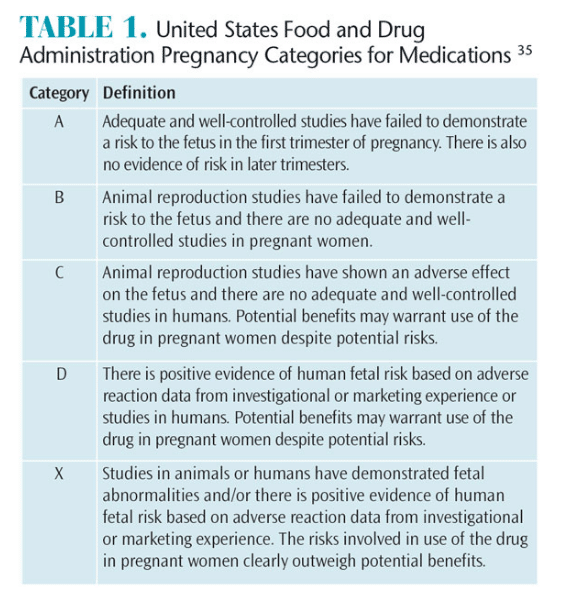

The main concern of drug administration during pregnancy is the possibility of teratogenic drugs crossing the placental barrier. The United States Food and Drug Administration has created a classification system for medications based on their risk to the fetus (Table 1).35 Many medications recommended for mild to moderate pain may be safely taken when used as directed.7 If an oral health professional is unsure of the appropriate regimen, or if the patient is experiencing acute dental pain, the prenatal care provider should be consulted.

Patient comfort and preventing medical emergencies are important considerations when treating pregnant patients. Pregnant women should be assessed for their ability to tolerate care. If a patient is experiencing morning sickness, the appointment may need to be scheduled at a different time or later in the pregnancy. Patients may require adjustments in appointment lengths to ensure comfort. In general, pregnant patients who are in their first or second trimesters can be positioned in supine to semi-reclined positions. In the third trimester, when the weight of the fetus may compress major blood vessels, a patient may be best positioned in a semi-reclined position or on her left side. A pillow or blanket can help support this position.

ORAL HYGIENE

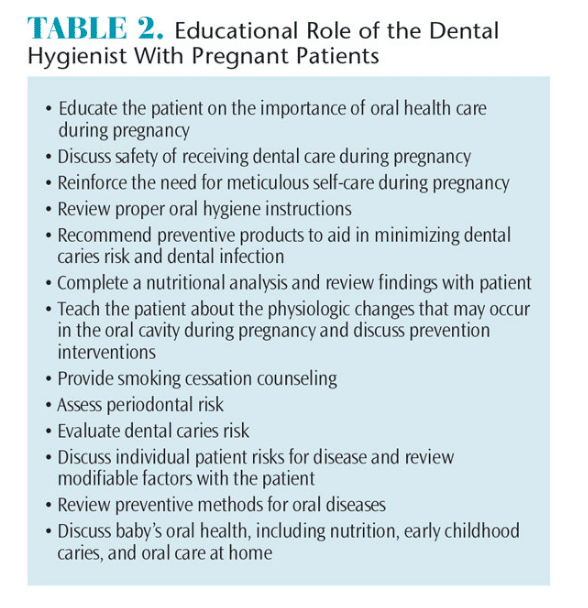

Dental hygienists can assess and review disease risk, offer nutritional recommendations, provide smoking cessation strategies, and discredit myths about pregnancy. Educating patients about the importance of receiving dental care during pregnancy is essential to improving oral and overall health (Table 2).

Each patient’s needs, complaints, and clinical findings must be considered when tailoring therapy recommendations. Occurrence and frequency of morning sickness, presence and/or increase in acid reflux, biofilm control, gingival health, social and health history, and nutritional status can all affect treatment outcomes. Consider questions such as: Does the patient have gingival inflammation or bleeding tissues? How is her self-care? How much biofilm is present and where? What is the patient’s risk for caries and periodontitis? Would she benefit by using additional fluoride or antigingivitis chemotherapeutic agents?

Patients experiencing vomiting from morning sickness should be advised to avoid brushing their teeth immediately after vomiting and to rinse their mouths with a teaspoon of baking soda dissolved in a cup of water to help neutralize acidity.23 If brushing with toothpaste causes gagging, brushing with a wet toothbrush followed by rinsing with a fluoride mouthrinse to promote remineralization can be recommended.

Pregnant women may experience an increase in dental caries resulting from a changed diet and/or reduced self-care efforts. Reinforcing the need for effective self-care and use of fluoride products will help reduce caries risk. Over-the-counter fluoride toothpastes and prescription high-fluoride toothpastes should be considered for patients at increased caries risk. The addition of antigingivitis mouthrinses and toothpastes may help to eliminate or control biofilm, thus enhancing gingival health.

Increased levels of untreated dental caries/ tooth loss among mothers increase the risk of poor oral health in their children.36 Children of mothers who had high levels of untreated caries are more than three times as likely to develop caries than mothers without decay.36 Talking with pregnant patients about oral health is vital to creating a pathway for good infant oral health. Evidence also suggests that most infants acquire caries-causing bacteria from their mothers. Habits such as kissing the baby on the lips and licking dirty pacifiers to clean them actually transmit harmful bacteria to the baby. Providing expectant mothers information on prevention may help reduce the risk of early childhood caries.7

CONCLUSION

Pregnancy is not a reason to abstain from receiving professional dental care. Clinicians should educate pregnant patients about the importance of receiving treatment throughout pregnancy. A thorough evaluation should include oral tissue assessment, risk factors for diseases, nutrition guidance, and oral health education. Clinical procedures should include diagnostic, preventive, and therapeutic efforts aimed at eliminating oral diseases.

References

- Vergnes JN, Sixou M. Preterm low birth weight andmaternal periodontal status: a meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:135.

- Lee RS, Milgrom P, Huebner CE, Conrad DA. Dentists’ perceptions of barriers to providing dental care to pregnant women. Women’s Health Issues. 2010;20:359–365.

- Dasanayake AP, Chhun N, Tanner ACR, et al. Periodontal pathogens and gestational diabetes mellitus. J Dent Res. 2008;87:328–333.

- Strafford KE, Shellhaas C, Hade EM. Provider and patient perceptions about dental care during pregnancy. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2008;21:63–71.

- Hagai A, Diav-Citrin O, Shechtman S. Pregnancy outcome after in utero exposure to local anesthetics as part of dental treatment: A prospective comparative cohort study. J Am Dent Assoc. 2015;146:572–580.

- Boggess KA, Edelstein BL. Oral health in women during preconception and pregnancy: implications for birth outcomes and infant oral health. Matern Child Health J. 2006;10(Suppl 5):S169–S174.

- Oral Health Care During Pregnancy Expert Workgroup. Oral Health Care During Pregnancy: A National Consensus Statement. Available at: mchoralhealth.org/PDFs/Oralhealthpregnancyconsensusmeetingsummary.pdf. Accessed February 3, 2016.

- Hwang S, Smith V, McCormick M, Barfield W. Racial/ethnic disparities in maternal oral health experiences in 10 states, pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system, 2004-2006. Matern Child Health J.2011;15:722–729.

- Pina PM, Douglass J. Practices and opinions of Connecticut general dentists regarding dental treatment during pregnancy. Gen Dent. 2011;59:e25–e31.

- Lachat MF, Solnik AL, Nana AD, Citron TL. Periodontal disease in pregnancy: review of evidence and prevention strategies. J Perinat Neonat Nurs. 2011;25:312–319.

- Wilder R, Robinson C, Jared HL, Lieff S, Boggess K. Obstetricians’ Knowledge and Practice behaviors concerning periodontal health and preterm delivery and low birth weight. J Dent Hyg. 2007;81:81.

- Vamos CA, Thompson EL, Avendano M, Daley EM, Quinonez RB, Boggess K. Oral health promotion interventions during pregnancy: a systematic review. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2015;43:385–396.

- Michalowicz BS, Gustafsson A, Thumbigere-Math V, Buhlin K. The effects of periodontal treatment on pregnancy outcomes. J Clin Periodontol. 2013;40(Suppl14):195–208.

- Boggess KA, Lieff S, Murtha AP, Moss K, Beck J, Offenbacher S. Maternal, periodontal disease is associated with an increased risk for preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:227–231.

- Offenbacher S, Lieff S, Boggess KA, et al. Maternal periodontitis and prematurity. Part I: obstetric outcome of prematurity and growth restriction. Ann Periodontol. 2001;6:164–174.

- Moore S, Ide M, Coward PY, et al. A prospective study to investigate the relationship between periodontal disease and adverse pregnancy outcome. Br Dent J. 2004;197:251–258.

- Mills LW, Moses DT. Oral Health during pregnancy. Am J of Maternal Child Nurs. 2002;27:275–280.

- Offenbacher S. Jared H. O’Reilly, et al. Potential pathogenic mechanism of periodontitis-associated pregnancy complications. Ann Periodontol. 1998;3:233–250. Offenbacher S. What Every Woman Needs to Know. Scientific American. 2006:24–29.

- Offenbacher S., Katz, V, Fertik G, et al. Periodontal infection as a possible risk factor for preterm low birth weight. J Periodontol. 1996;67:1103–1113.

- Offenbacher S, Beck JD, Jared HL, et al. Effects of periodontal therapy on rate of preterm delivery: a randomized control trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114:551–559.

- Michalowicz, Hodges, DiAngelis, et al. Treatment of periodontal disease and the risk of preterm birth. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1885–1894. Silk J, Douglass AB, Douglass JM, Silk L. Oral healthduring pregnancy. Am Fam Physician. 2008;77:1139–1144.

- Manegold-Brauer G, Brauer HU. Oral pregnancy tumour: an update. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;34:187–188.

- Michalowicz BS, DiAngelis AJ, Novak JM, et al. Examining the safety of dental treatment in pregnant women. J Am Dent Assoc. 2008;139:685–695.

- Achtari MD, Georgakopoulou EA, Afentoulide N. Dental care throughout pregnancy: what a dentist must know. Oral Health Dent Manag. 2012;11:169–176.

- Wrzosek T, Einarson A. Dental care during pregnancy. Canadian Fam Physician. 2009;55:598–599.

- Rowland AS, Baird DD, Weinberg CR, Shore DL, Shy CM, Wilcox AJ. Reduced fertility among women employed as dental assistants exposed to high levels of nitrous oxide. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:993–997.

- Heidam LZ. Spontaneous abortions among dental assistants, factory workers, painters, and gardening workers: a follow up study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1984;38:149–155.

Melkonian R, Baker D. Risks of industrial mercury exposure in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1988;43:637–641. - Task Force on Periodontal Treatment of Pregnant Women, American Academy of Periodontology. American Academy of Periodontology statement regarding periodontal management of the pregnantpatient. J Periodontol. 2004;75:495.

- American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Number 299: Guidelines for diagnostic imaging during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:647–651.

- Kumar V. Radiography and the pregnant patient. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2013;11(1):56–61.

- Stein EJ, Weintraub JA, Brown C, et al. Oral health during pregnancy and early childhood: evidenced based guidelines for health professionals. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2010;38:391–440.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. FDA Pregnancy Categories. Available at: chemm.nlm.nih.gov/pregnancycategories.htm. Accessed February 3, 2016.

- Dye BA, Vargas CM, Lee JJ, Magder L, Tinanoff N. Assessing the relationship between children’s oral health status and that of their mothers. J Am Dent Assoc. 2011;142:173–183.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. March 2016;14(03):52,55–57.