PHOENIXNS/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

PHOENIXNS/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

Hypersensitivity in the Orthodontic Patient

Hard tissue and soft tissue hypersensitivity may be experienced by patients undergoing different types of orthodontic treatment.

Hypersensitivity in the orthodontic patient can be broadly categorized into two types: hard tissue hypersensitivity, commonly known as dentinal hypersensitivity, and soft tissue hypersensitivity, which is mainly caused by allergies to orthodontic materials. This article provides a brief overview of hypersensitivity issues encountered in orthodontic patients, both during and after treatment.

DENTINAL HYPERSENSITIVITY

Dentinal hypersensitivity refers to short episodes of sharp pain caused by exposed dentin in response to thermal, tactile, osmotic, or chemical stimuli, with the most common being cold and acidic foods. It is not associated with any other form of dental defect or pathology.1,2 Dentinal hypersensitivity can restrict daily activities and quality of life, which frequently motivates patients to seek treatment. Studies have shown a significant improvement in oral health-related quality of life after dentinal hypersensitivity is successfully addressed.3–5

Various etiological factors can contribute to dentinal hypersensitivity, including tooth whitening, high consumption of acidic food and drinks, and poor toothbrushing technique, resulting in gingival recession. In orthodontic patients, hypersensitivity is most commonly attributed to interproximal enamel reduction (IER), a procedure involving the reduction, recontouring, and polishing of interproximal enamel surfaces. This procedure is commonly used in orthodontics as an alternative to extractions and arch expansion in patients presenting with mild to moderate crowding. IER is also frequently used to address tooth size discrepancy to achieve an ideal occlusion at the end of orthodontic treatment.

Research shows that dentinal hypersensitivity affects between 8% and 54% of the general population, with women more likely to develop it than men.6,7 On the other hand, the incidence of IER-induced dentinal hypersensitivity is low.8 Long-term follow-up (10 years) of orthodontic patients who received IER on all six mandibular anterior teeth showed that only one of the 61 participants developed increased sensitivity of the mandibular incisors.8

Prior to performing IER, the clinician must evaluate the amount of enamel that can be safely removed. Because interdental enamel is thinner on mandibular incisors and maxillary lateral incisors, IER must be limited to 0.5 mm at these contact points.9 To avoid removing excess enamel, all teeth must be aligned and rotations corrected prior to IER. This allows for accurate assessment of enamel thickness on each tooth. For posterior teeth with thicker enamel, up to 1.0 mm per contact area can be safely removed.9

Three techniques are most commonly used for IER: air-rotor stripping with diamond or carbide burs; diamond-coated discs on a handpiece (Figure 1); and handheld abrasive metal strips (Figure 2). A study measuring enamel loss by subtraction radiography showed that IER performed with handheld abrasive strips removed significantly less enamel than IER conducted with diamond burs.10 If air-rotor stripping is chosen for IER, tooth surfaces must be adequately cooled to avoid overheating, which could cause irreversible pulp damage. Regardless of the IER method, all interproximal surfaces must be polished after enamel stripping. This ensures smooth surfaces, which prevents excessive plaque accumulation and consequent demineralization of the tooth surface.11

Transient hypersensitivity is sometimes observed in orthodontic patients who undergo orthognathic jaw surgery or alveolar corticotomies for accelerated orthodontic tooth movement. Hernandez-Alfaro and Guijarro-Martinez12 reported transient dentinal hypersensitivity in one of nine subjects post-surgery, which was resolved in 5 weeks.

A small amount of gingival recession can occur on one or more teeth during orthodontic treatment. A study of young adults showed that patients with prior orthodontic treatment showed higher incidence of localized gingival recession than untreated subjects.13 If left untreated, this might result in dentinal hypersensitivity from exposed root surfaces.14

Enamel wear from occluding on orthodontic brackets can lead to dentinal hypersensitivity. Maxillary incisal edges and buccal cusps of posterior teeth can experience significant wear from occluding on orthodontic brackets, especially ceramic brackets, which are highly abrasive. Heavy occlusal contacts can also lead to excessive wear of enamel, exposing coronal dentin to the oral environment, and resulting in hypersensitivity.2

Care must be taken to prevent enamel wear from orthodontic appliances. This can be achieved by temporary disocclusion of the teeth directly occluding on brackets during treatment. Some patients present with localized gingival recession prior to orthodontic treatment (labially blocked-out canines). If the path of tooth movement is expected to worsen the recession, a soft tissue graft prior to orthodontic treatment may be considered.

HYPERSENSITIVITY MANAGEMENT

The efficient management of dentinal hypersensitivity relies primarily on proper diagnosis. Some dental conditions can lead to symptoms similar to those of dentinal hypersensitivity. A differential diagnosis should include cracked tooth syndrome, vital bleaching, fractured restorations, caries causing pulpal response, and others.

Dental hygienists can play a vital role in the prevention and management strategies for dentinal hypersensitivity, including:

- Patient education on proper toothbrushing technique during and after orthodontic treatment.

- Periodontal health status evaluations at regular intervals; periodontal therapy must be promptly initiated when indicated.

- Review of patient’s regular diet to screen for etiologic factors contributing to sensitivity.

- Evaluate patients for parafunctional habits; night-time splints may be considered for at-risk patients to help minimize wear of dentition.

Professional management of dentinal hypersensitivity is often based on the treatment results rather than underlying etiology or predisposing factors. Therefore, a wide range of products are available, many of which show similar efficacy. Treatment can include over-the-counter desensitizing agents, professionally administered agents, restorations, or surgical intervention. Unfortunately, no one treatment works for all. As such, developing a treatment plan specific to the patient’s diagnosis is critical. Factors that must be considered when treatment planning include patient’s age, medical history, oral hygiene and periodontal status, and severity of the sensitivity. A diagnosis can usually be made via tactile stimulus with a dental probe or an air jet. The ideal treatment for dentinal hypersensitivity must be fast acting, effective for long periods, easy to apply, nonirritating to pulpal tissues, and esthetically acceptable.15

For some patients, spontaneous relief can occur over time with remineralization and occlusion of exposed dentinal tubules. Several desensitizing agents are available for personal and professional application. These agents are available as dentifrices, gels, mouthwashes, varnishes, and dental resins or adhesives.16

Dentifrices are the most commonly used desensitizing agent. Advantages of this application method include reduced costs and easy, at-home application with a toothbrush. Dentifrices usually feature desensitizing agents, such as potassium nitrate, stannous fluoride, sodium fluoride, sodium monofluorphosphate, strontium chloride, and others. Their mechanism of action is based on the obliteration of dentinal tubules, caused by calcium phosphate precipitation on the dentin surface.17 For professional application, in case of no significant loss or weakening of the dental structure, products such as fluoride varnishes, potassium oxalate, resin sealants, and others can be used. For patients with enamel wear from orthodontic brackets, composite resins can be applied to seal and protect. In cases with significant wear of incisal edges, restorative build-ups can be considered, as they offer functional, esthetic, and protective benefits.

Dentifrices are the most commonly used desensitizing agent. Advantages of this application method include reduced costs and easy, at-home application with a toothbrush. Dentifrices usually feature desensitizing agents, such as potassium nitrate, stannous fluoride, sodium fluoride, sodium monofluorphosphate, strontium chloride, and others. Their mechanism of action is based on the obliteration of dentinal tubules, caused by calcium phosphate precipitation on the dentin surface.17 For professional application, in case of no significant loss or weakening of the dental structure, products such as fluoride varnishes, potassium oxalate, resin sealants, and others can be used. For patients with enamel wear from orthodontic brackets, composite resins can be applied to seal and protect. In cases with significant wear of incisal edges, restorative build-ups can be considered, as they offer functional, esthetic, and protective benefits.

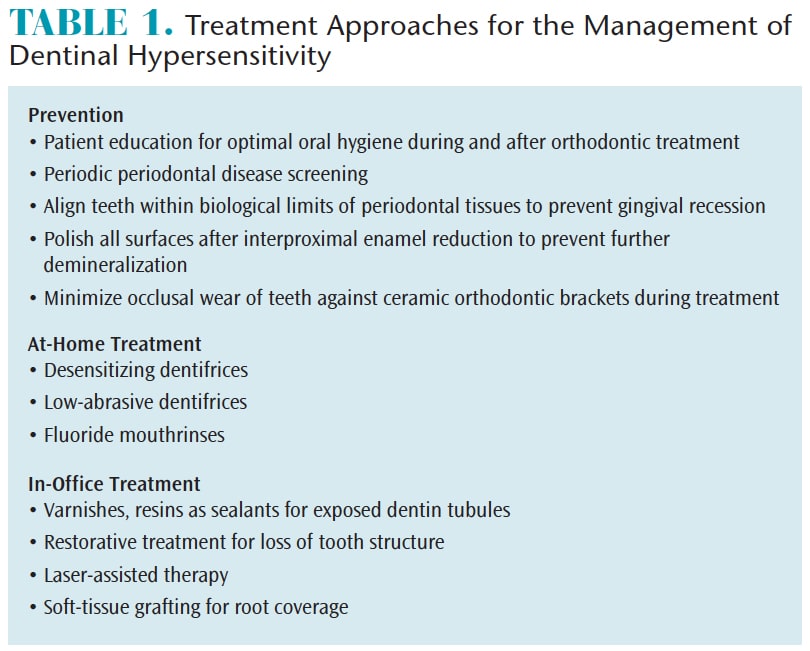

Research suggests that laser-assisted therapy can provide relief from sensitivity-related pain. This is an innovative, fast-acting treatment, with minimal side effects. The diode laser can be used for this application, given its safety and beneficial clinical results.18For patients experiencing sensitivity due to gingival recession post-orthodontic treatment, soft tissue grafting provides good prognosis and improved esthetics.14 Table 1 provides a comprehensive overview of dentinal hypersensitivity treatment.

SOFT TISSUE HYPERSENSITIVITY

Short-term and long-term soft tissue sensitivity may be caused by nickel, a strong biologic sensitizer. It may cause contact allergy on the skin and lead to a type IV delayed hypersensitivity immune response. Nickel sensitivity is estimated to affect about 10% of the general population, with women more frequently impacted than men.19 However, oral mucosal reactions to nickel are rare, even in individuals sensitive to nickel. This may be due to oral mucosal membranes being less sensitive than the skin. Therefore, the oral concentration of nickel needed to provoke a reaction is higher than what is required for skin.20 Pazzini et al19 found that nickel can influence the periodontal condition and increase band cells in sensitive individuals, indicating that this reaction is of an inflammatory, rather than allergic nature.

MANAGEMENT OF SOFT TISSUE HYPERSENSITIVITY

Prior to treatment, a proper history and questionnaire can help detect nickel sensitivity, as most individuals will have encountered nickel exposure in the past and learned of their allergy. For sensitive patients, a good alternative is titanium brackets and wires.21 Ceramic brackets can also be used instead of metal brackets. For patients with mild to moderate malocclusions, clear aligners can be considered, as they have improved esthetics, cause fewer clinical emergencies,22 and are removable for daily oral hygiene practices. If a diagnosis is missed prior to treatment and the patient develops a reaction to the appliance, immediate removal is recommended. Sensitivity is usually self-corrected after removal of appliances. If needed, the patient’s primary care physician can be consulted or the patient may be referred to an allergist for patch testing to confirm clinical findings.

Patients with latex allergies may experience sensitivity to elastomeric ligatures and orthodontic elastics.23 In patients with sensitivity, self-ligating brackets or steel ligatures can be used to replace elastomeric ligatures, and the treatment plan can be modified to avoid use of elastics for correction of class 2 and class 3 malocclusions.

CONCLUSION

Oral health professionals who are well versed in the two types of hypersensitivity—hard tissue and soft tissue—will be prepared to provide their patients with solutions to decrease the impact of hypersensitivity on quality of life and support the success of orthodontic treatment.

REFERENCES

- Dowell P, Addy M. Dentine hypersensitivity-—a review. Aetiology, symptoms and theories of pain production. J Clin Periodontol. 1983;10:341–350.

- Porto IC, Andrade AK, Montes MA. Diagnosis and treatment of dentinal hypersensitivity. J Oral Sci. 2009;51:323–332.

- Jalali Y, Lindh L. A randomized prospective clinical evaluation of two desensitizing agents on cervical dentine sensitivity. A pilot study. Swed Dent J. 2010;34:79–86.

- Douglas de Oliveira DW, Marques DP, Aguiar-Cantuária IC, Flecha OD, Gonçalves PF. Effect of surgical defect coverage on cervical dentin hypersensitivity and quality of life. J Periodontol. 2013;84:768–775.

- Douglas de Oliveira DW, Vitor GP, Silveira JO, Martins CC, Costa FO, Cota LOM. Effect of dentin hypersensitivity treatment on oral health related quality of life – A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dent. 2018;71:1–8.

- Markowitz K, Pashley DH. Personal reflections on a sensitive subject. J Dent Res. 2007;86:292–295.

- Addy M, Urquhart E. Dentine hypersensitivity: its prevalence, aetiology and clinical management. Dent Update. 1992;19:407–412.

- Zachrisson BU, Nyoygaard L, Mobarak K. Dental health assessed more than 10 years after interproximal enamel reduction of mandibular anterior teeth. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2007;131:162–169.

- Chaudasama D, Sheridan JJ. Guidelines for contemporary air rotor stripping. J Clin Orthod. 2007;41:315–320.

- Danesh G, Hellak A, Lippold C, Ziebura T, Schafer E. Enamel surfaces following interproximal reduction with different methods. Angle Orthod. 2007;77:1004–10010.

- Radlanski RJ, Jager A, Schwestka R, Bertzbach F. Plaque accumulations caused by interdental stripping. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1988;94:416–420.

- Hernández-Alfaro F, Guijarro-Martínez R. Endoscopically assisted tunnel approach for minimally invasive corticotomies: a preliminary report. J Periodontol. 2012;83:574–580.

- Slutzkey S, Levin L. Gingival recession in young adults: Occurrence, severity, and relationship to past orthodontic treatment and oral piercing. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2008;1:652–656.

- Kassab MM, Badawi H, Dentino AR. Treatment of gingival recession. Dent Clin North Am. 2010;54:129–140.

- Grossman L. A systematic method for treatment of hypersensitive dentine. J Am Dent Assoc. 1935;22:592–598.

- West NX. Dentine hypersensitivity: preventive and therapeutic approaches to treatment. Periodontol 2000. 2008;48:31–41.

- Arrais CA, Micheloni CD, Giannini M, Chan DC. Occluding effect of dentifrices on dentinal tubules. J Dent. 2003;31:577–584.

- Biagi R, Cossellu G, Sarcina M, Pizzamiglio IT, Farronato G. Laser-assisted treatment of dentinal hypersensitivity: a literature review. Ann Stomatol (Roma). 2016;6:75–80.

- Pazzini CA, Pereira LJ, Carlos RG, de Melo GE, Zampini MA, Marques LS. Nickel: periodontal status and blood parameters in allergic orthodontic patients. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2011;139:55–59.

- Haberman AL, Pratt M, Storrs FJ. Contact dermatitis from beryllium in dental alloys. Contact Dermatitis. 1993;28:157–162.

- Kusy RP. Clinical response to allergies in patients. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2004;125:544–547.

- Buschang PH, Shaw SG, Ross M, Crosby D, Campbell PM. Comparative time efficiency of aligner therapy and conventional edgewise braces. Angle Orthod 2014; 84:391–396.

- Hain LA, Longman LP, Field EA, Harrison JE. Natural rubber latex allergy: Implications for the orthodontist. J Orthod. 2007;34:6–11.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. April 2018;16(4):16-18.